Similar presentations:

SOF108 - Computer Architecture Week 14: Parallel Processing – Pipelining

1. SOF108 - Computer Architecture Week 14: Parallel Processing – Pipelining

MALAYSIASOF108 - Computer Architecture

Week 14: Parallel Processing – Pipelining

1

2. Agenda

• Pipelining• Hazards in Pipeline

• Dependencies in Pipeline

• How to avoid hazards?

• Stall

• Forward

• Prediction

• Delayed branch

2

3. What is Instruction Level Parallelism (ILP)?

• Goal of ILP is to execute several instructions simultaneously to make theprogram run faster

• Some instructions are independent of others

• We don’t always have to wait for all previous instructions to execute before

executing a given instruction

• If independent instructions are executed in parallel, the program runs

faster

3

4. Increase Computer Performance

• Can be achieved by taking advantage of improvements in technology,such as faster circuitry

• In addition, organization enhancements to the processor can improve

performance

• We have seen some examples of this:

• Use of multiple registers rather than a single accumulator,

• use of cache memory

• Another common organizational approach is:

• Instruction Pipelining

4

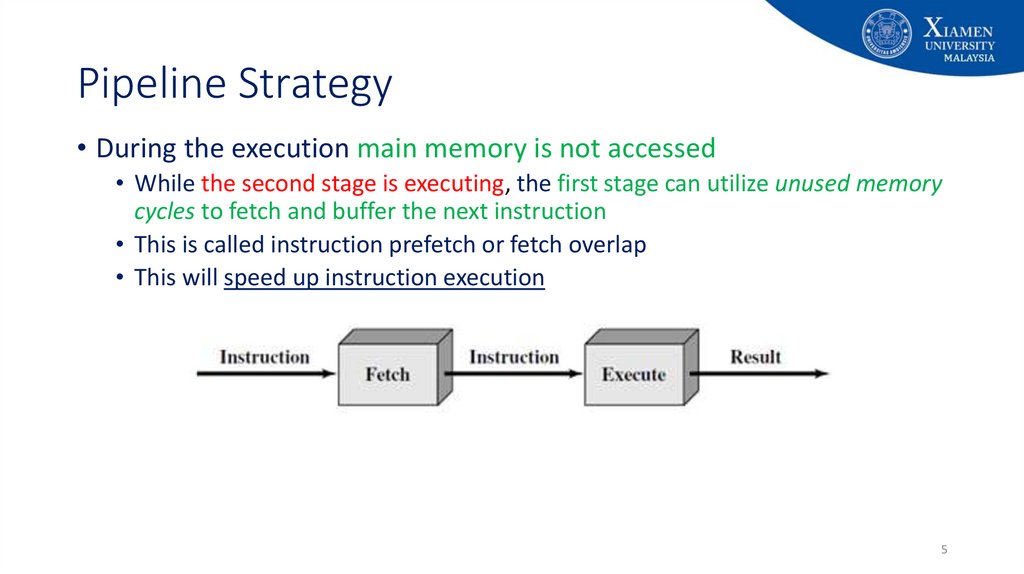

5. Pipeline Strategy

• During the execution main memory is not accessed• While the second stage is executing, the first stage can utilize unused memory

cycles to fetch and buffer the next instruction

• This is called instruction prefetch or fetch overlap

• This will speed up instruction execution

5

6. Pipelining

• Decompose a sequential process into sub-operation, with each suboperation completed in dedicated segment.• It is similar like assembly line of car manufacturing.

• First station in an assembly line installing the engine, next station is

fitting the body, another group of workers working on the paint.

6

7. Pipelining in Assembly Line

78. Pipelining Laundry Example: It is Natural

• Ann, Brian, Cathy, Daveeach have one load of clothes

to wash, dry, and fold

A

B

C

D

• Washer takes 30 minutes

• Dryer takes 40 minutes

• “Folder” takes 20 minutes

8

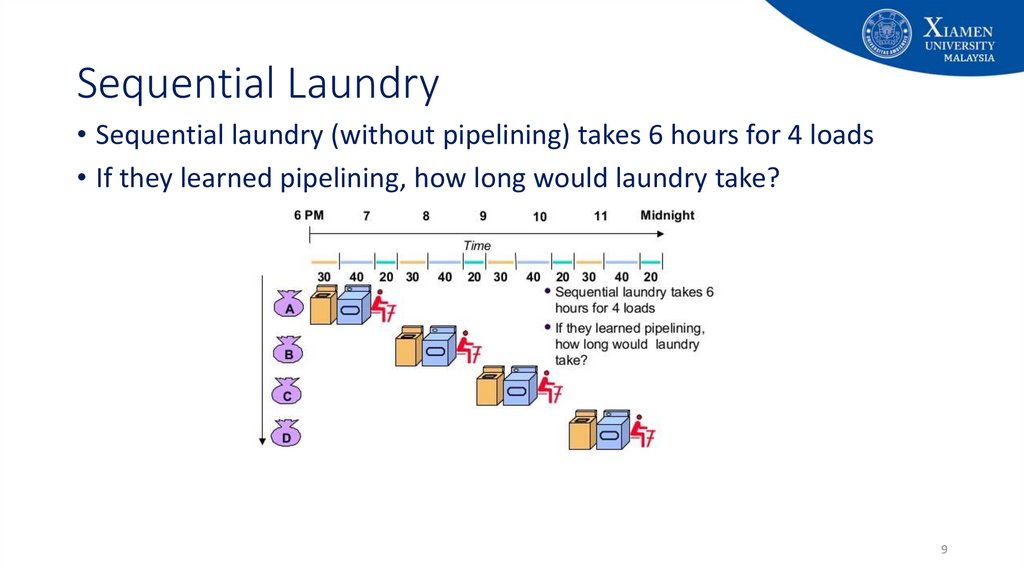

9. Sequential Laundry

• Sequential laundry (without pipelining) takes 6 hours for 4 loads• If they learned pipelining, how long would laundry take?

9

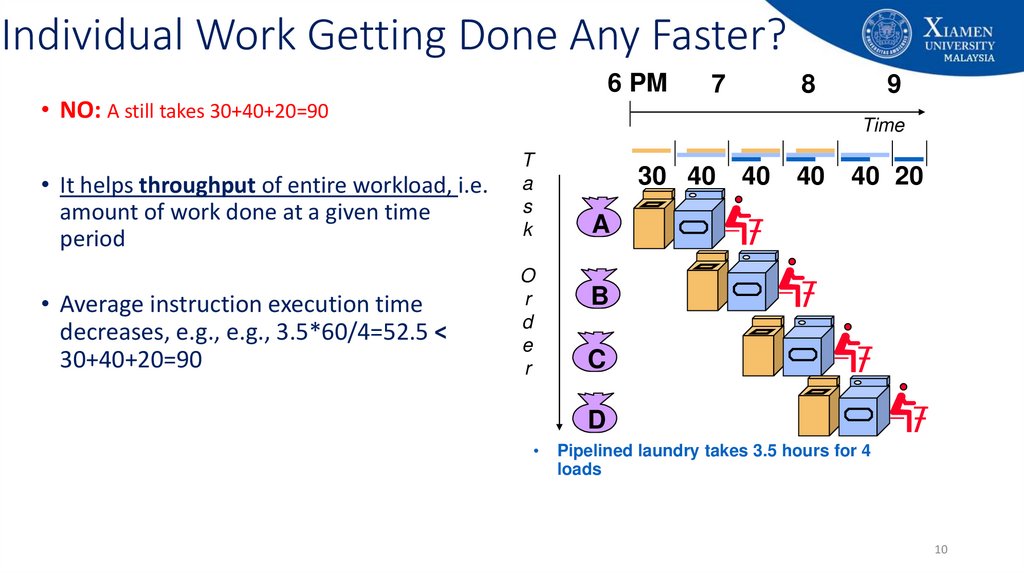

10.

Individual Work Getting Done Any Faster?6 PM

• NO: A still takes 30+40+20=90

• It helps throughput of entire workload, i.e.

amount of work done at a given time

period

• Average instruction execution time

decreases, e.g., e.g., 3.5*60/4=52.5 <

30+40+20=90

7

8

9

Time

T

a

s

k

O

r

d

e

r

30 40

40

40

40 20

A

B

C

D

Pipelined laundry takes 3.5 hours for 4

loads

10

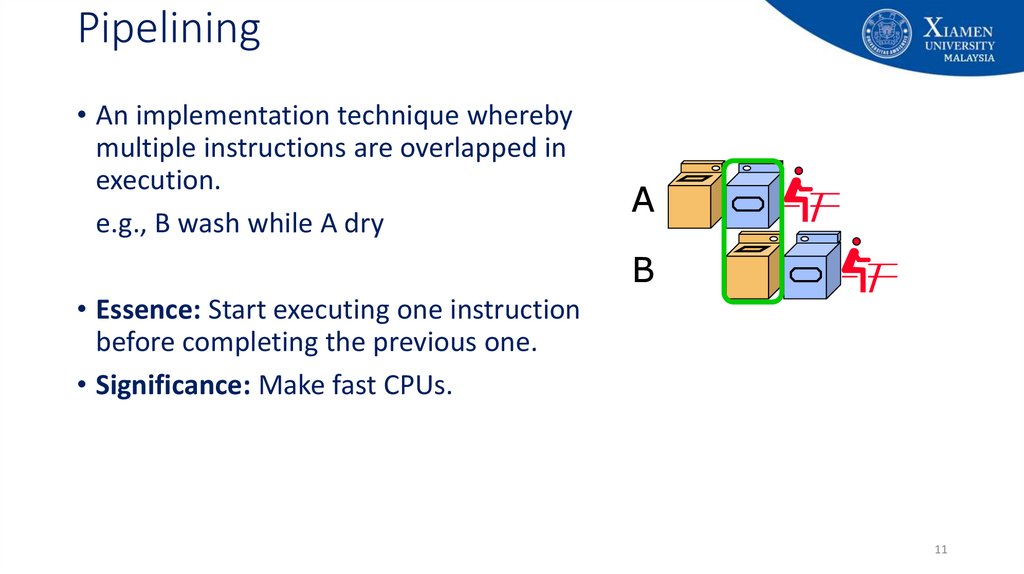

11. Pipelining

• An implementation technique wherebymultiple instructions are overlapped in

execution.

e.g., B wash while A dry

A

B

• Essence: Start executing one instruction

before completing the previous one.

• Significance: Make fast CPUs.

11

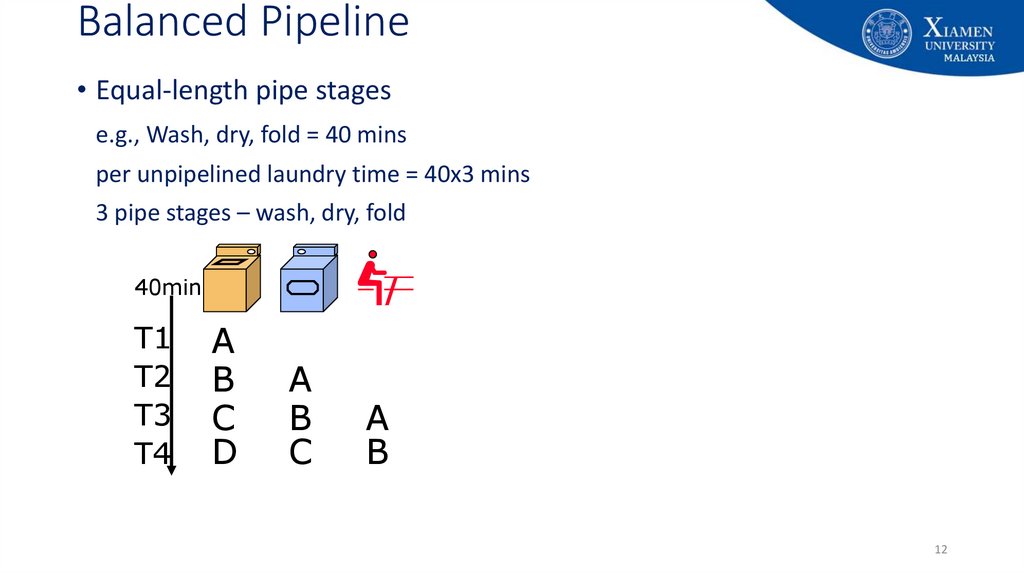

12. Balanced Pipeline

• Equal-length pipe stagese.g., Wash, dry, fold = 40 mins

per unpipelined laundry time = 40x3 mins

3 pipe stages – wash, dry, fold

40min

T1

T2

T3

T4

A

B

C

D

A

B

C

A

B

12

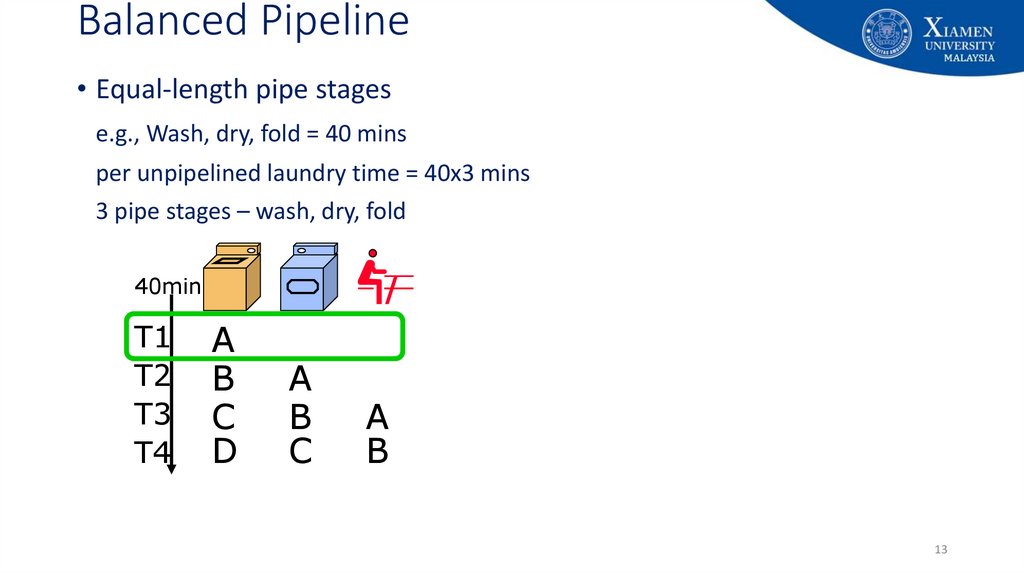

13. Balanced Pipeline

• Equal-length pipe stagese.g., Wash, dry, fold = 40 mins

per unpipelined laundry time = 40x3 mins

3 pipe stages – wash, dry, fold

40min

T1

T2

T3

T4

A

B

C

D

A

B

C

A

B

13

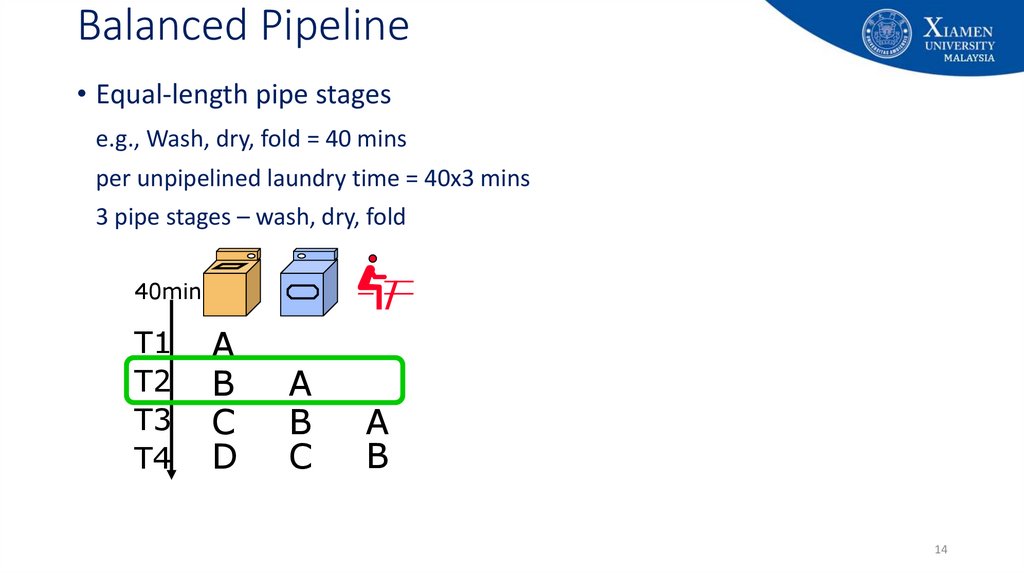

14. Balanced Pipeline

• Equal-length pipe stagese.g., Wash, dry, fold = 40 mins

per unpipelined laundry time = 40x3 mins

3 pipe stages – wash, dry, fold

40min

T1

T2

T3

T4

A

B

C

D

A

B

C

A

B

14

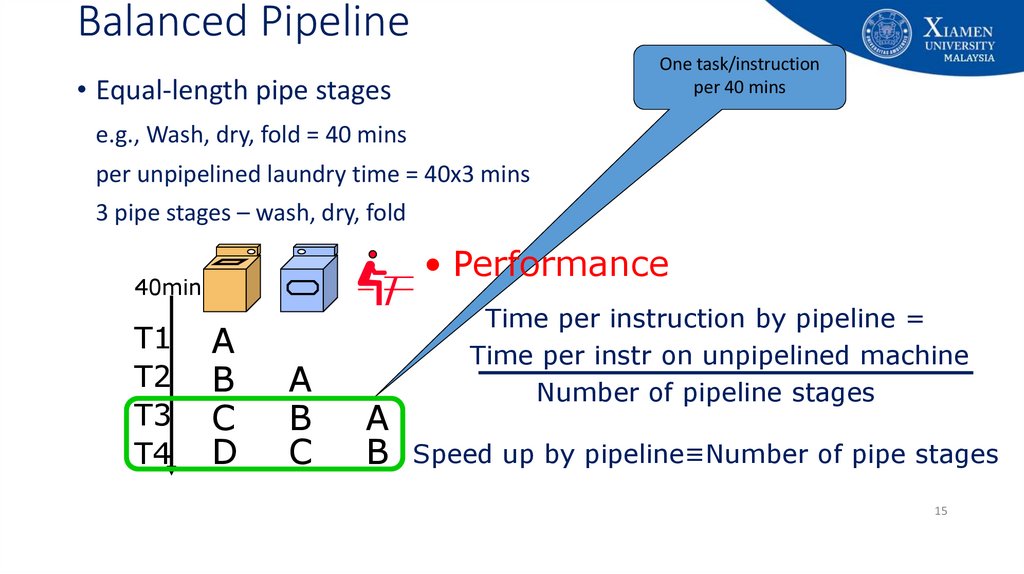

15. Balanced Pipeline

One task/instructionper 40 mins

• Equal-length pipe stages

e.g., Wash, dry, fold = 40 mins

per unpipelined laundry time = 40x3 mins

3 pipe stages – wash, dry, fold

• Performance

40min

T1

T2

T3

T4

A

B

C

D

A

B

C

Time per instruction by pipeline =

Time per instr on unpipelined machine

Number of pipeline stages

A

B Speed up by pipeline≡Number of pipe stages

15

16. Pipelining Performance

• Each instruction is split up into a sequence of steps – different steps can be executedconcurrently by different circuitry.

• The potential increase in performance resulting from pipelining is proportional to the

number of pipeline stages.

• However, this increase would be achieved only if all pipeline stages require the same

time to complete, and there is no interruption throughout program execution.

• Unfortunately, this is NOT true.

• Pipeline rate limited by slowest pipeline stage.

• Unbalanced lengths of pipe stages reduces speedup

• Effect of branching

16

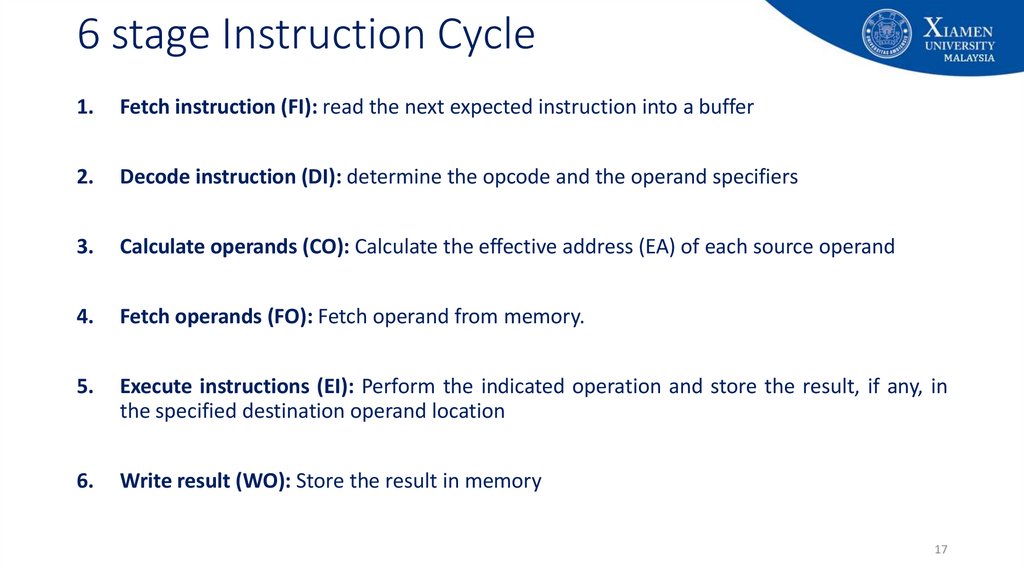

17. 6 stage Instruction Cycle

1.Fetch instruction (FI): read the next expected instruction into a buffer

2.

Decode instruction (DI): determine the opcode and the operand specifiers

3.

Calculate operands (CO): Calculate the effective address (EA) of each source operand

4.

Fetch operands (FO): Fetch operand from memory.

5.

Execute instructions (EI): Perform the indicated operation and store the result, if any, in

the specified destination operand location

6.

Write result (WO): Store the result in memory

17

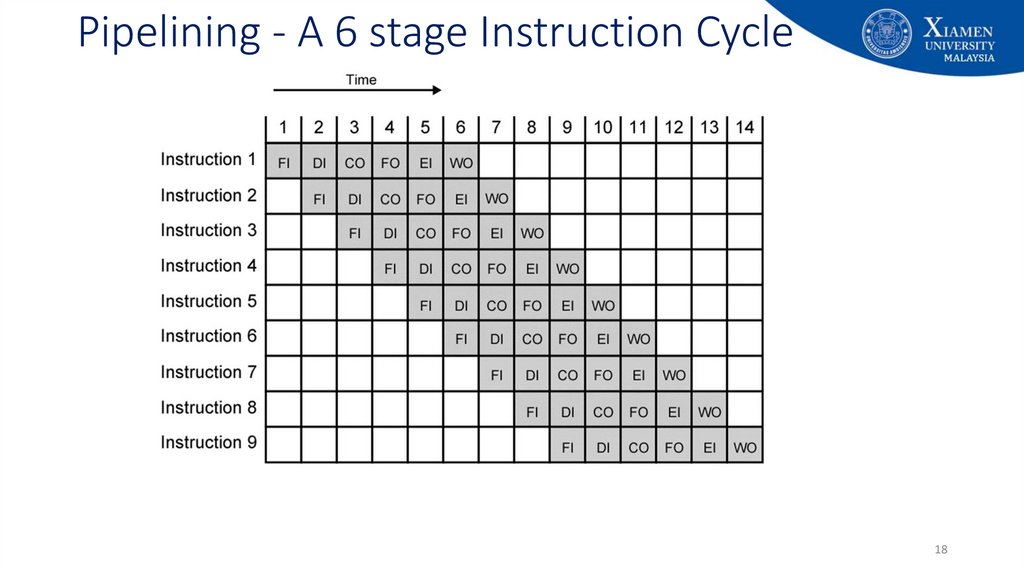

18. Pipelining - A 6 stage Instruction Cycle

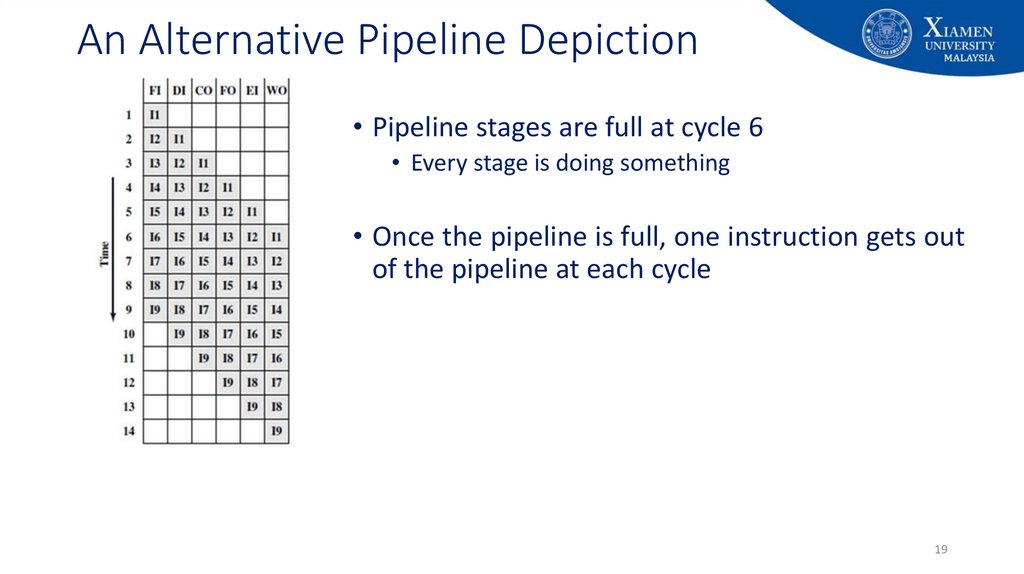

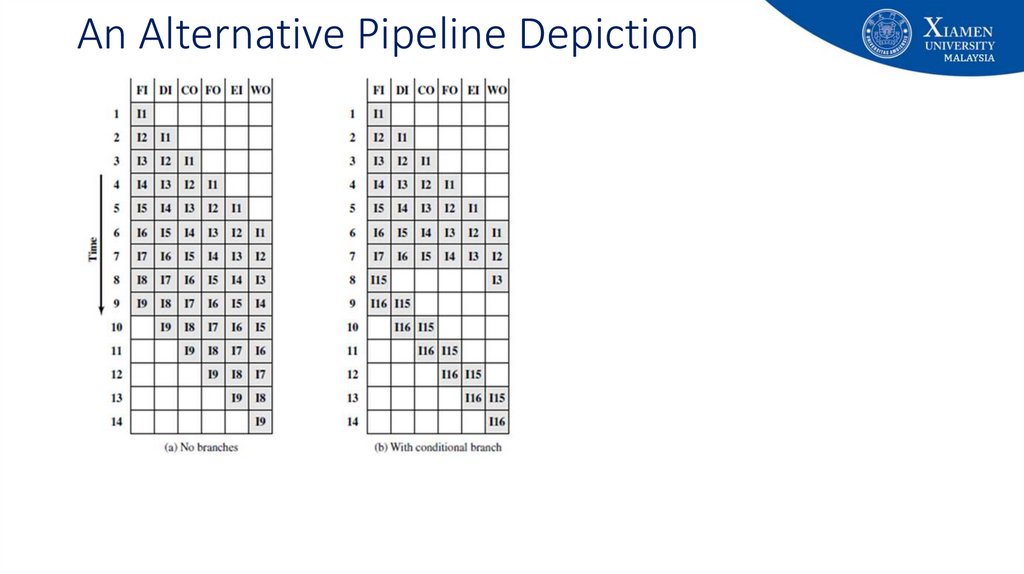

1819. An Alternative Pipeline Depiction

• Pipeline stages are full at cycle 6• Every stage is doing something

• Once the pipeline is full, one instruction gets out

of the pipeline at each cycle

19

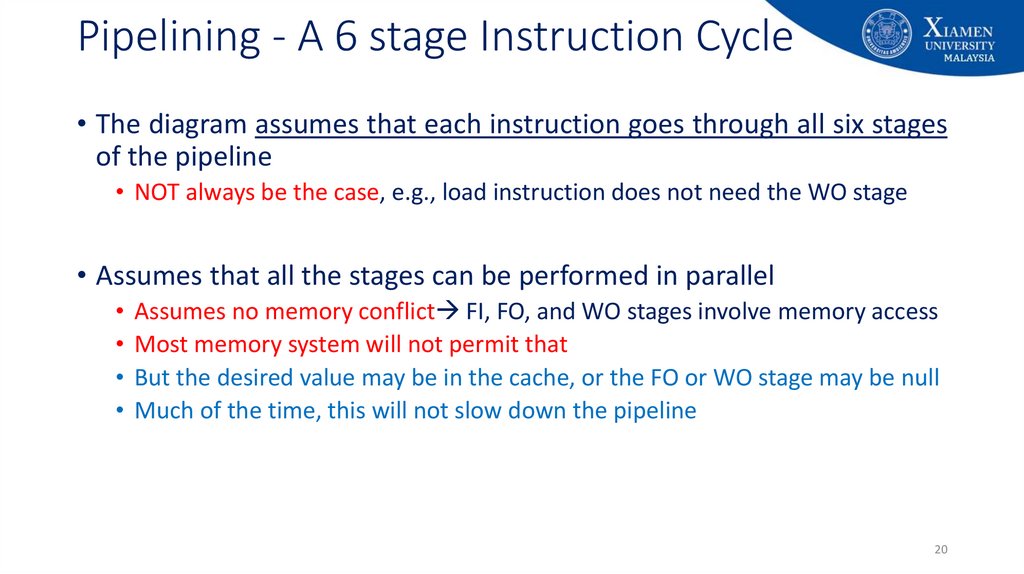

20. Pipelining - A 6 stage Instruction Cycle

• The diagram assumes that each instruction goes through all six stagesof the pipeline

• NOT always be the case, e.g., load instruction does not need the WO stage

• Assumes that all the stages can be performed in parallel

• Assumes no memory conflict FI, FO, and WO stages involve memory access

• Most memory system will not permit that

• But the desired value may be in the cache, or the FO or WO stage may be null

• Much of the time, this will not slow down the pipeline

20

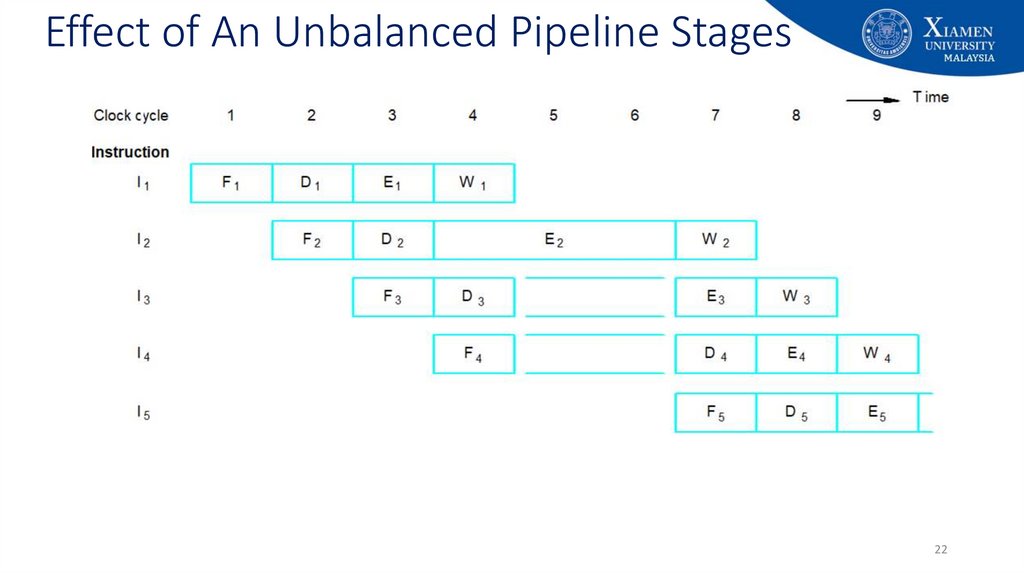

21. Pipelining - A 6 stage Instruction Cycle

• If the six stages are not of equal duration, there will be some waiting involved atvarious pipeline stages

• Another difficulty is conditional branch instruction

• Can invalidate several instruction fetches

• The CO stage may depend on the contents of a register that could be altered by a

previous instruction that is still in the pipeline

• Other such register and memory conflict may occur

• The system must contain logic for this type of conflicts

21

22. Effect of An Unbalanced Pipeline Stages

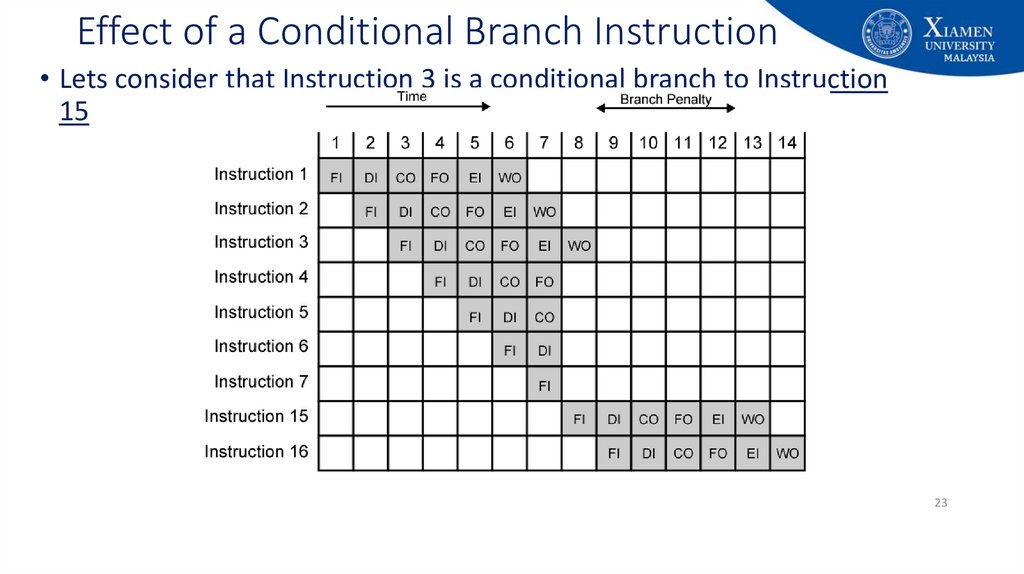

2223. Effect of a Conditional Branch Instruction

• Lets consider that Instruction 3 is a conditional branch to Instruction15

23

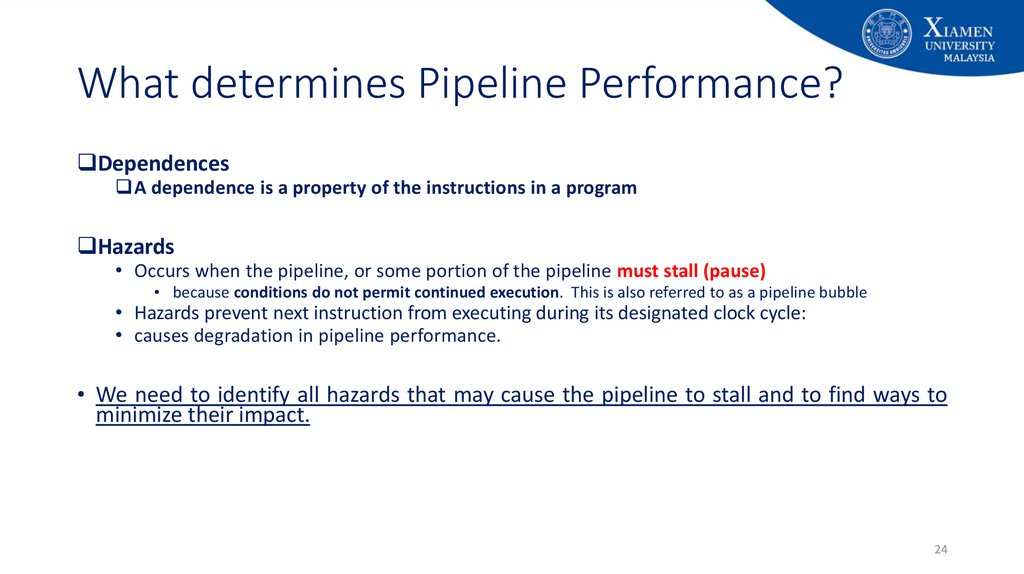

24. What determines Pipeline Performance?

DependencesA dependence is a property of the instructions in a program

Hazards

• Occurs when the pipeline, or some portion of the pipeline must stall (pause)

• because conditions do not permit continued execution. This is also referred to as a pipeline bubble

• Hazards prevent next instruction from executing during its designated clock cycle:

• causes degradation in pipeline performance.

• We need to identify all hazards that may cause the pipeline to stall and to find ways to

minimize their impact.

24

25. Pipeline Hazard

• Three types• Resource hazard/ Structural hazard

• Data hazard

• Control hazard

25

26. Resource Hazard/Structural hazard

• A resource hazard occurs when two (or more instructions) that arealready in the pipeline need the same resource

• Requires serial execution rather than parallel for a portion of the pipeline

• If some combination of instructions cannot be accommodated

because of resource conflicts (hardware conflicts), the machine is

said to have structural hazard/ resource hazard.

26

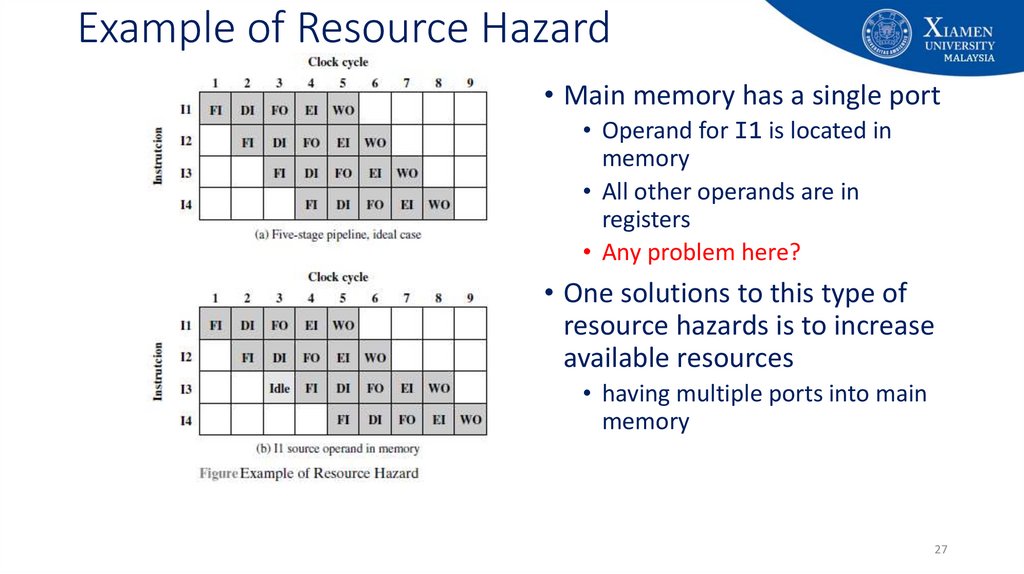

27. Example of Resource Hazard

• Main memory has a single port• Operand for I1 is located in

memory

• All other operands are in

registers

• Any problem here?

• One solutions to this type of

resource hazards is to increase

available resources

• having multiple ports into main

memory

27

28. Example of Resource Hazard

• Another example of a resource conflict is a situation in which multipleinstructions are ready to enter the execute instruction phase and

there is a single ALU.

• One solutions to such resource hazards is to increase available

resources,

• having multiple ALU units.

28

29. Data Hazard

• Data hazard occurs when there is a conflict in the access of anoperand location.

• Generally, Data hazards arise when an instruction depends on the

results of a previous instruction in a way that is exposed by the

overlapping of instructions in the pipeline

29

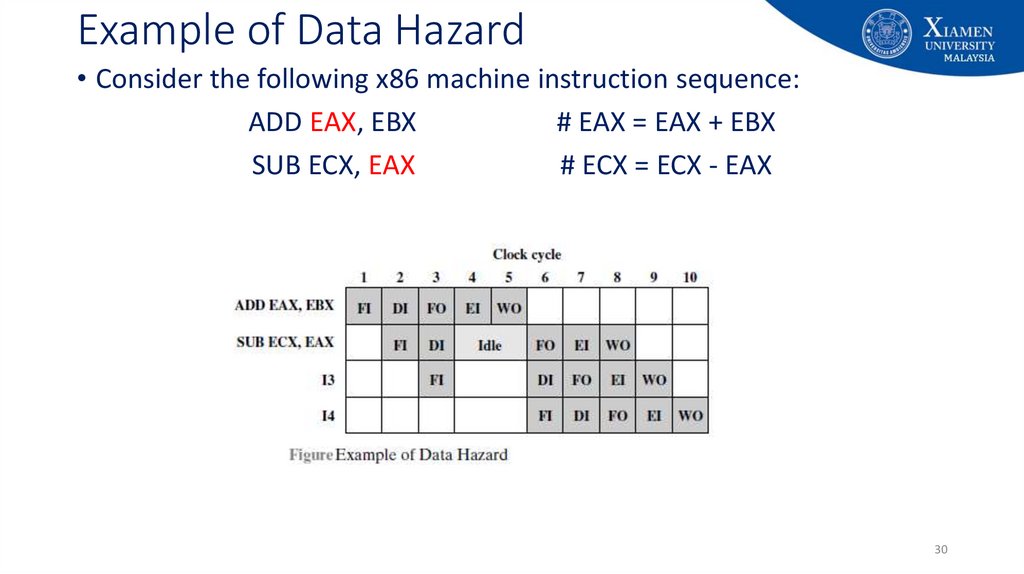

30. Example of Data Hazard

• Consider the following x86 machine instruction sequence:ADD EAX, EBX

# EAX = EAX + EBX

SUB ECX, EAX

# ECX = ECX - EAX

30

31. Data Hazards

• Three types of data hazards:• Read after write (RAW), or true dependency

• Write after read (WAR), or antidependency

• Write after Write (WAW), or output dependency

31

32. Read after Write (RAW)

• An instruction modifies (writes) a register or memory location and asucceeding instruction reads the data in that memory or register

location

• A hazard occurs if the read takes place before the write operation is

complete.

• Example:

• Add R1, R2, R3

• Add R4, R1, R5

32

33. Write after Read (WAR)

• An instruction reads a register or memory location and a succeedinginstruction writes to the location

• A hazard occurs if the write operation completes before the read

operation takes place

• Example:

• I: sub r4, r1, r3

• J: add r1, r2, r3

• K: mul r6, r1, r7

33

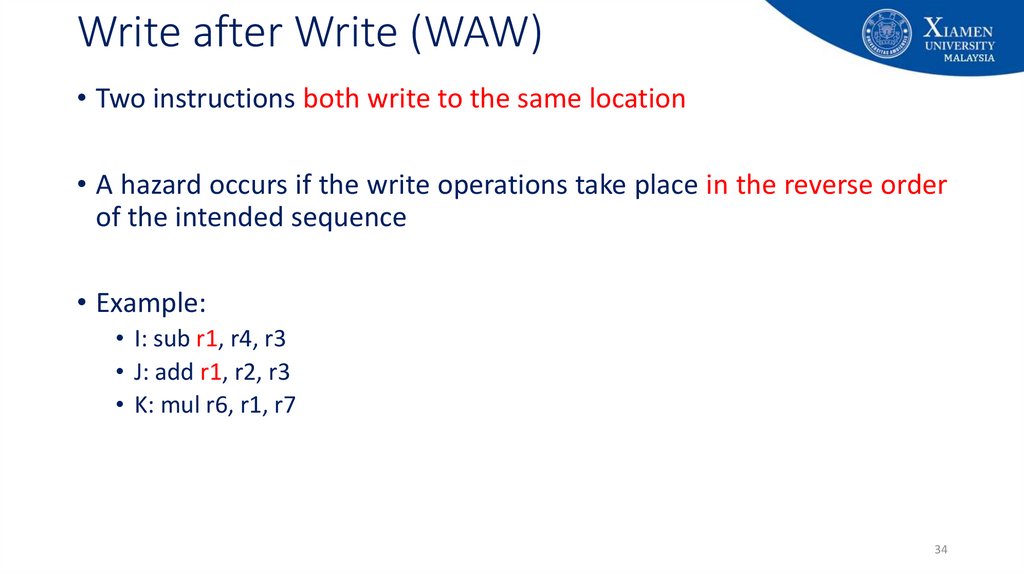

34. Write after Write (WAW)

• Two instructions both write to the same location• A hazard occurs if the write operations take place in the reverse order

of the intended sequence

• Example:

• I: sub r1, r4, r3

• J: add r1, r2, r3

• K: mul r6, r1, r7

34

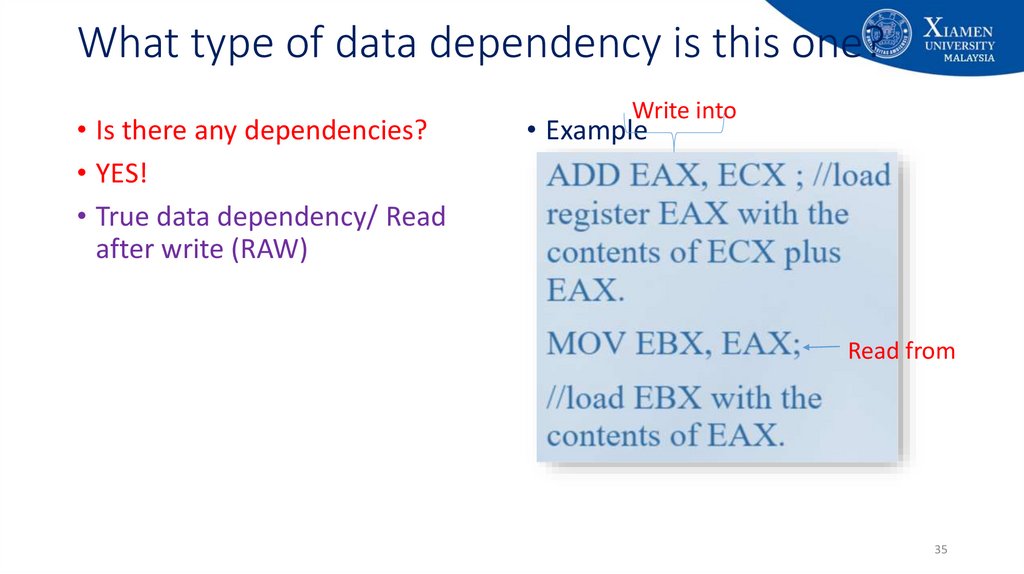

35. What type of data dependency is this one?

• Is there any dependencies?• YES!

• True data dependency/ Read

after write (RAW)

Write into

• Example

Read from

35

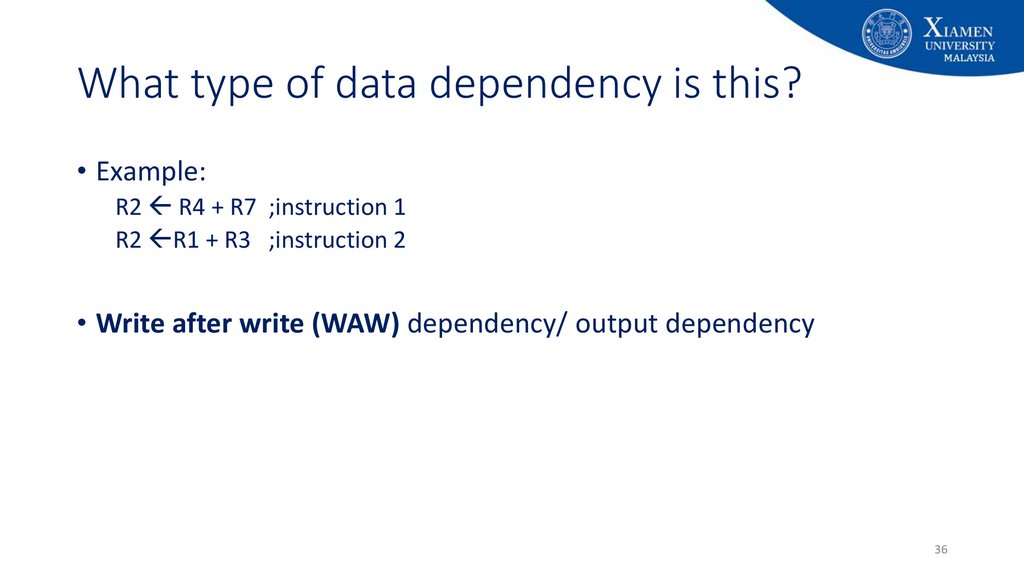

36. What type of data dependency is this?

• Example:R2 R4 + R7 ;instruction 1

R2 R1 + R3 ;instruction 2

• Write after write (WAW) dependency/ output dependency

36

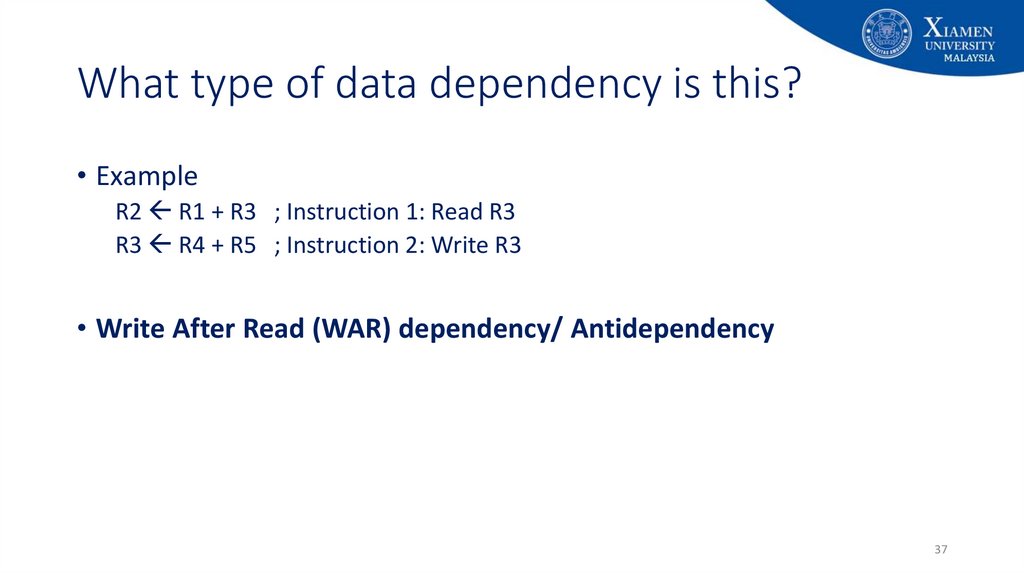

37. What type of data dependency is this?

• ExampleR2 R1 + R3 ; Instruction 1: Read R3

R3 R4 + R5 ; Instruction 2: Write R3

• Write After Read (WAR) dependency/ Antidependency

37

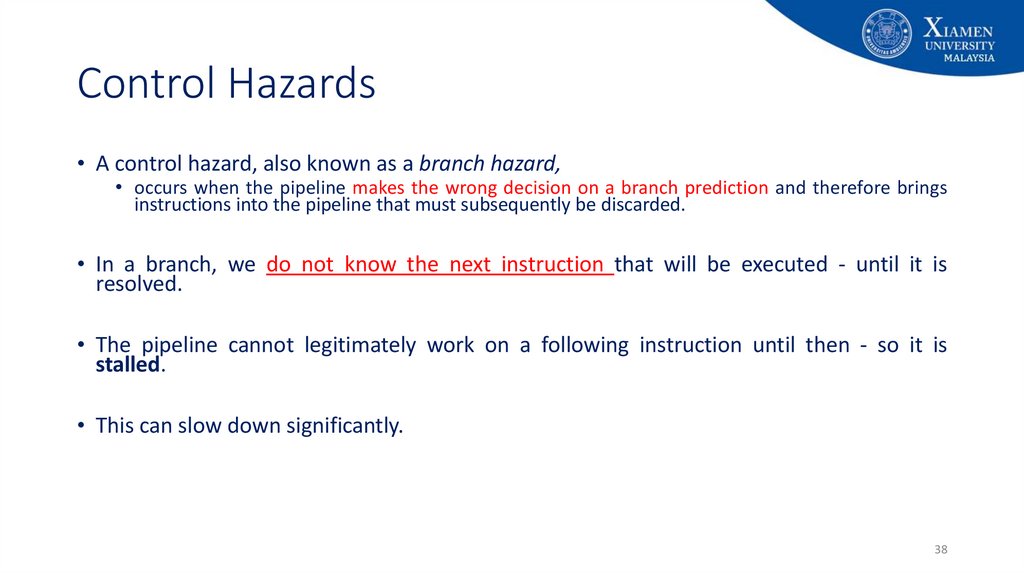

38. Control Hazards

• A control hazard, also known as a branch hazard,• occurs when the pipeline makes the wrong decision on a branch prediction and therefore brings

instructions into the pipeline that must subsequently be discarded.

• In a branch, we do not know the next instruction that will be executed - until it is

resolved.

• The pipeline cannot legitimately work on a following instruction until then - so it is

stalled.

• This can slow down significantly.

38

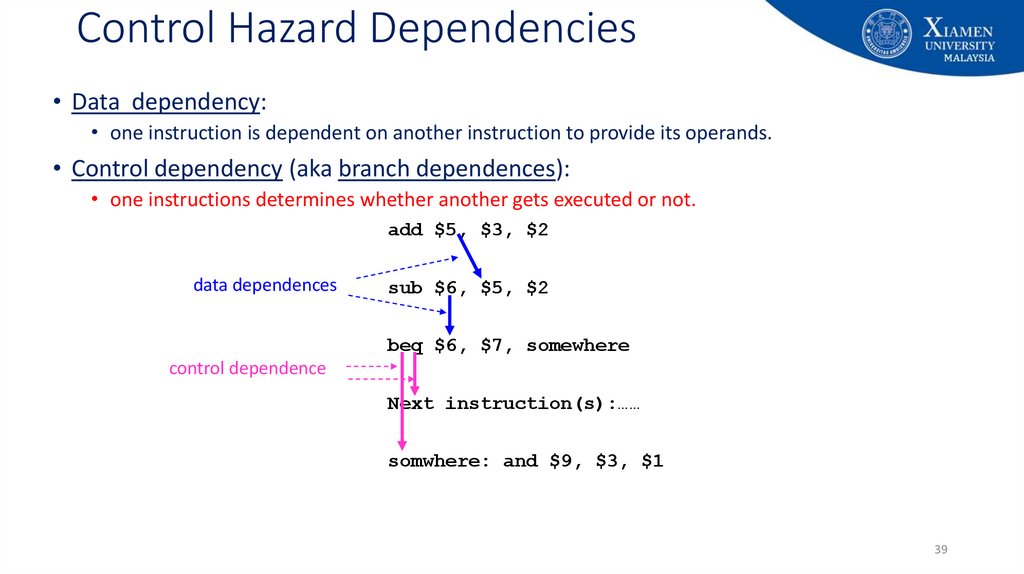

39. Control Hazard Dependencies

• Data dependency:• one instruction is dependent on another instruction to provide its operands.

• Control dependency (aka branch dependences):

• one instructions determines whether another gets executed or not.

add $5, $3, $2

data dependences

sub $6, $5, $2

beq $6, $7, somewhere

control dependence

Next instruction(s):……

somwhere: and $9, $3, $1

39

40. Control Hazard Example

• Lets consider thatInstruction 3 is a

conditional branch

to Instruction 15

• Assume that the

output of the branch

is known only after

the execution stage

• Let the pipeline

predict that the

branch is not taken

40

41. An Alternative Pipeline Depiction

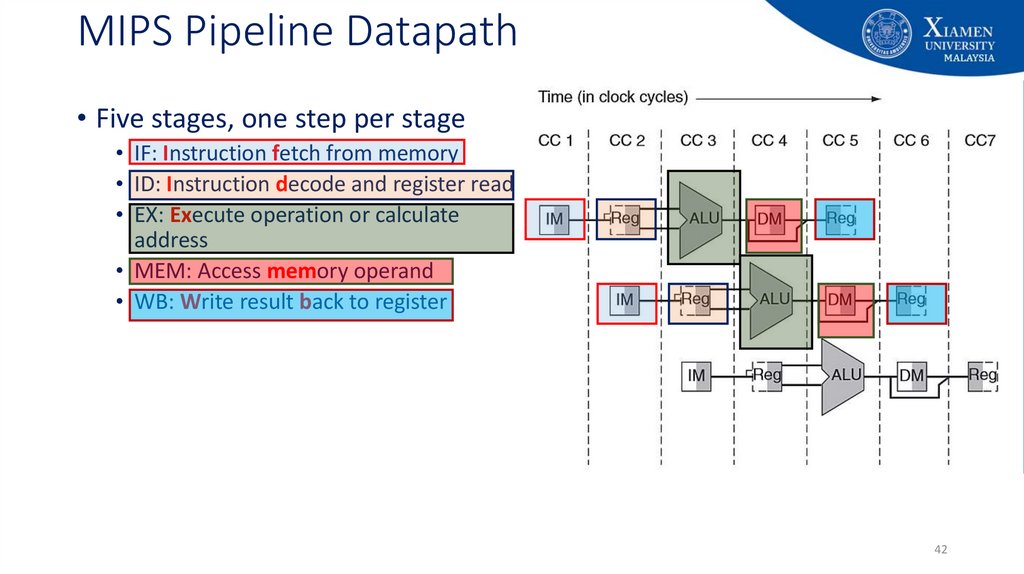

42. MIPS Pipeline Datapath

• Five stages, one step per stage• IF: Instruction fetch from memory

• ID: Instruction decode and register read

• EX: Execute operation or calculate

address

• MEM: Access memory operand

• WB: Write result back to register

42

43. Pipeline: Number of Stages?

• Bigger the better?• From the preceding discussion, it may appear that the larger the

number of stages in the pipeline, the faster the execution rate.

• Speed up by pipeline ≡ Number of pipe stages

• However, there are some additional things that we need to consider!

43

44. Pipeline: Number of Stages?

• At each stage, there is some overhead involved in moving data from bufferto buffer, and in performing various preparation and delivery functions.

• This overhead can appreciably lengthen the total execution time of a single

instruction

• The amount of control logic increases enormously with the number of

stages

• required to handle memory and register dependencies and

• to optimize the use of the pipeline

44

45. Uniformity is Simplicity

• Enforce Uniformity• Make all instructions take five cycles

• Make them have the same stages, in the same order

• Some stages will do nothing for some instructions

45

46. A Simple Implementation of a RISC Instruction

• Every instruction in MIPS can be implemented in at most 5 clock cycles. The 5 clockcycles are:

• Instruction fetch cycle (IF)

• Instruction decode/ register fetch cycle (ID)

• Execution/effective address cycle (EX)

• Memory access (MEM)

• Write-back cycle (WB)

46

47. Instruction Fetch Cycle (IF)

• Send the program counter (PC) to memory and fetch the currentinstruction from memory.

• IR:= Memory[PC]

• Update the PC to the next sequential PC by adding 4 (since each

instruction is 4 bytes) to the PC.

• PC:= PC+4

47

48. Instruction Decode/Register Fetch cycle (ID)

• Decode the instruction and read the registers corresponding to registersource specifiers from the register file.

• ADD R1, R2, R3

• Do the equality test on the registers as they are read, for a possible branch.

• BEQ R1, R2, 5

• Decoding is done in parallel with reading registers

48

49. Execution/Effective Address Cycle (EX)

• Memory reference: The ALU adds the base register and the offset to form theeffective address. For example:

• LW R1, 0(R2)

• SW R4,12(R1)

• Register-Register ALU instruction: The ALU performs the operation specified by

the ALU opcode on the values read from the register file. For example:

• ADD R4, R1, R5

• Register-Immediate ALU instruction: The ALU performs the operation specified by

the ALU opcode on the first value read from the register file and the signextended immediate.

• ADDI R4, R1, 15

49

50. Memory Access (MEM)

• If the instruction is a load, memory does a read using the effectiveaddress computed in the previous cycle.

• LW R1, 0(R2)

• If it is a store, then the memory writes the data from the second

register read from the register file using the effective address.

• SW R4,12(R1)

50

51. Write-Back Cycle (WB)

• Register-Register ALU instruction or• Write the result into the register file from the ALU (for an ALU instruction)

• ADD R4, R1, R5

• Load instruction

• Write the result into the register file from the memory system (for a load)

• LW R1, 0(R2)

51

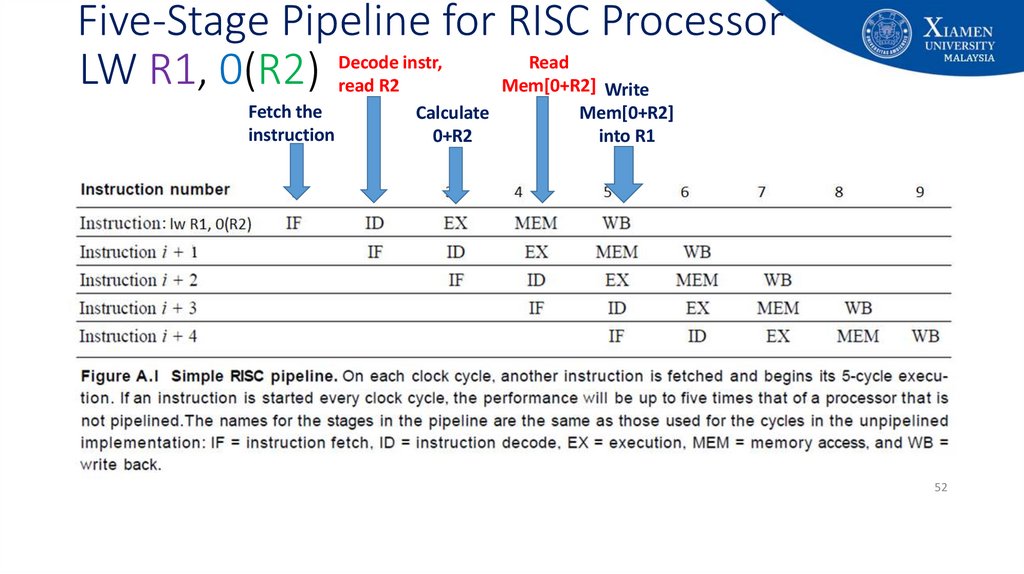

52. Five-Stage Pipeline for RISC Processor

Decode instr,Read

LW R1, 0(R2) read R2

Mem[0+R2] Write

Fetch the

instruction

Calculate

0+R2

Mem[0+R2]

into R1

52

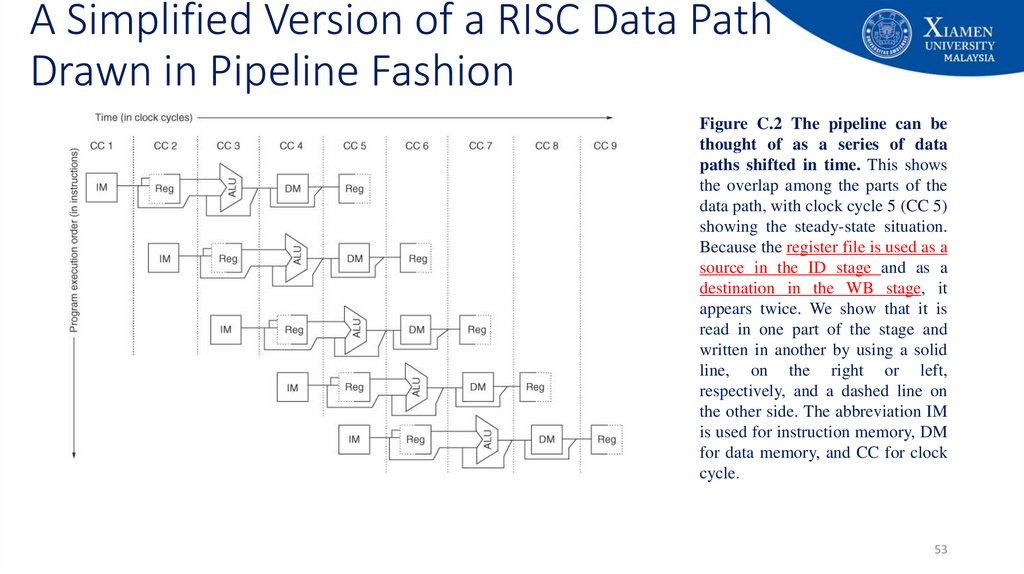

53. A Simplified Version of a RISC Data Path Drawn in Pipeline Fashion

Figure C.2 The pipeline can bethought of as a series of data

paths shifted in time. This shows

the overlap among the parts of the

data path, with clock cycle 5 (CC 5)

showing the steady-state situation.

Because the register file is used as a

source in the ID stage and as a

destination in the WB stage, it

appears twice. We show that it is

read in one part of the stage and

written in another by using a solid

line, on the right or left,

respectively, and a dashed line on

the other side. The abbreviation IM

is used for instruction memory, DM

for data memory, and CC for clock

cycle.

53

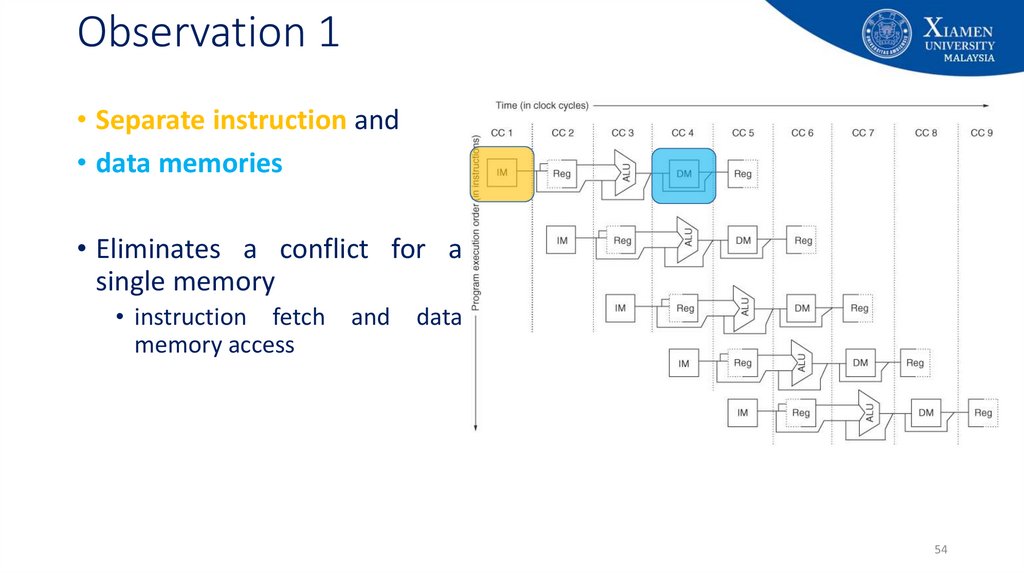

54. Observation 1

• Separate instruction and• data memories

• Eliminates a conflict for a

single memory

• instruction fetch

memory access

and

data

54

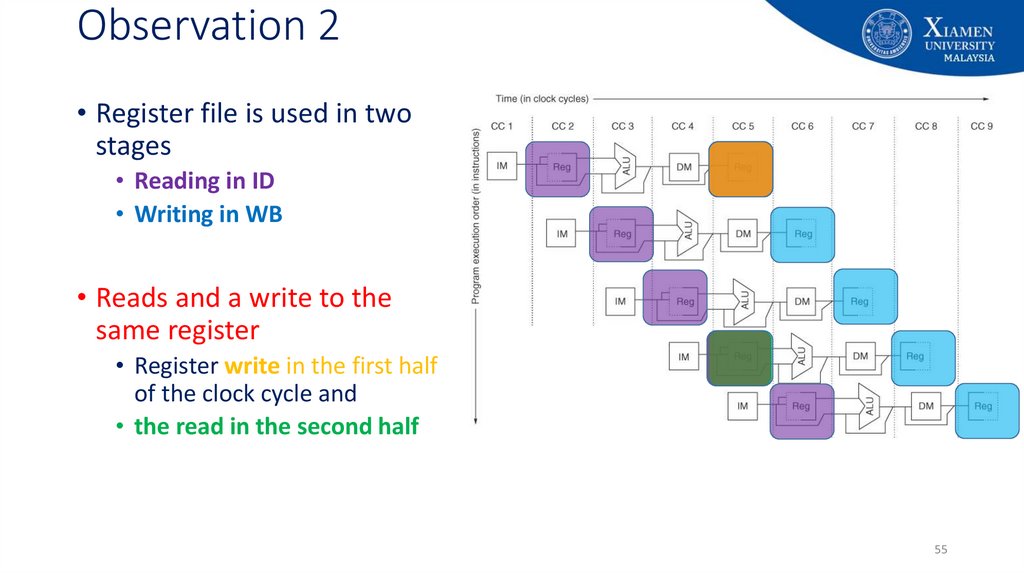

55. Observation 2

• Register file is used in twostages

• Reading in ID

• Writing in WB

• Reads and a write to the

same register

• Register write in the first half

of the clock cycle and

• the read in the second half

55

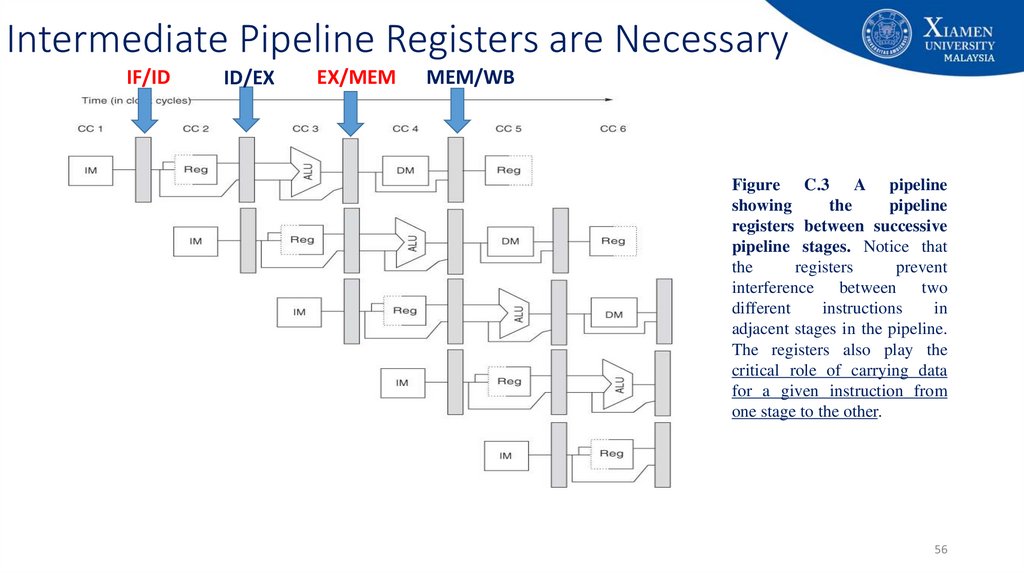

56. Intermediate Pipeline Registers are Necessary

IF/IDID/EX

EX/MEM

MEM/WB

Figure C.3 A pipeline

showing

the

pipeline

registers between successive

pipeline stages. Notice that

the

registers

prevent

interference between two

different

instructions

in

adjacent stages in the pipeline.

The registers also play the

critical role of carrying data

for a given instruction from

one stage to the other.

56

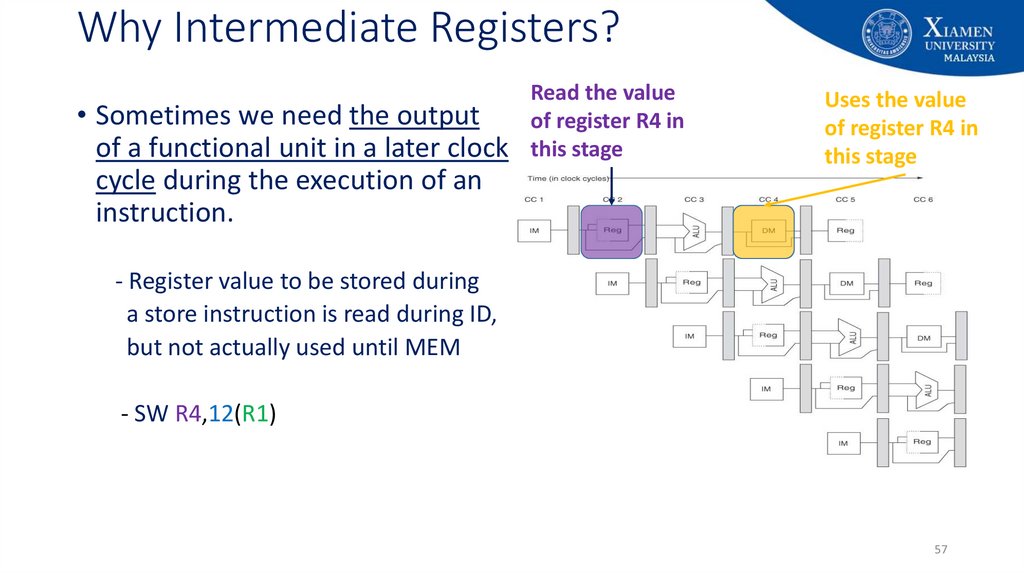

57. Why Intermediate Registers?

• Sometimes we need the outputof a functional unit in a later clock

cycle during the execution of an

instruction.

Read the value

of register R4 in

this stage

Uses the value

of register R4 in

this stage

- Register value to be stored during

a store instruction is read during ID,

but not actually used until MEM

- SW R4,12(R1)

57

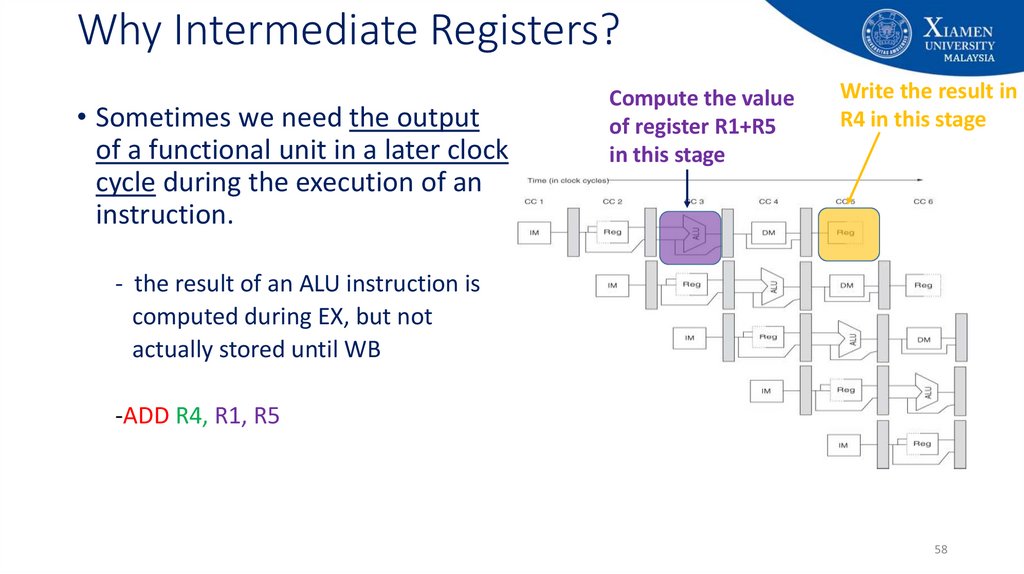

58. Why Intermediate Registers?

• Sometimes we need the outputof a functional unit in a later clock

cycle during the execution of an

instruction.

Compute the value

of register R1+R5

in this stage

Write the result in

R4 in this stage

- the result of an ALU instruction is

computed during EX, but not

actually stored until WB

-ADD R4, R1, R5

58

59. Basic Performance Issues in Pipelining

• Pipelining increases the CPU instruction throughput• the number of instructions completed per unit of time

• but it does not reduce the execution time of an individual instruction.

• In fact, it usually slightly increases the execution time of each

instruction due to overhead in the control of the pipeline.

• The increase in instruction throughput means that

• a program runs faster and has lower total execution time,

• even though no single instruction runs faster!

59

60. Pipeline is not Quite that Easy!

• Limits to pipelining: Hazards prevent next instruction from executing duringits designated clock cycle

• Structural hazards: hardware cannot support all possible combinations of

instructions simultaneously in overlapped execution.

• Data hazards: instruction depends on the results of a previous instruction

still in the pipeline.

• Control hazards: arise from the pipelining of branches and other

instructions that change the PC.

60

61. Major Hurdle of Pipelining – Pipeline Hazards

• Hazards in pipelines can make it necessary to stall the pipeline.• Avoiding a hazard often requires that

• some instructions in the pipeline be allowed to proceed

• while others are delayed.

• For the pipelines we discuss in this course, when an instruction is stalled, all

instructions issued later than the stalled instruction—and hence not as far along

in the pipeline—are also stalled.

• Instructions issued earlier than the stalled instruction—and hence farther along

in the pipeline—must continue, since otherwise the hazard will never clear. As a

result, no new instructions are fetched during the stall.

61

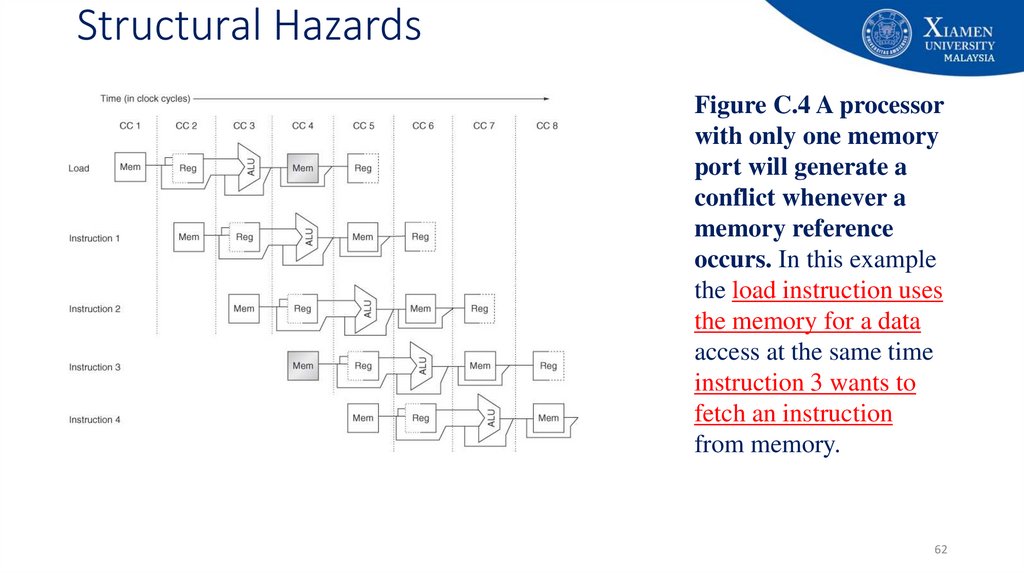

62. Structural Hazards

Figure C.4 A processorwith only one memory

port will generate a

conflict whenever a

memory reference

occurs. In this example

the load instruction uses

the memory for a data

access at the same time

instruction 3 wants to

fetch an instruction

from memory.

62

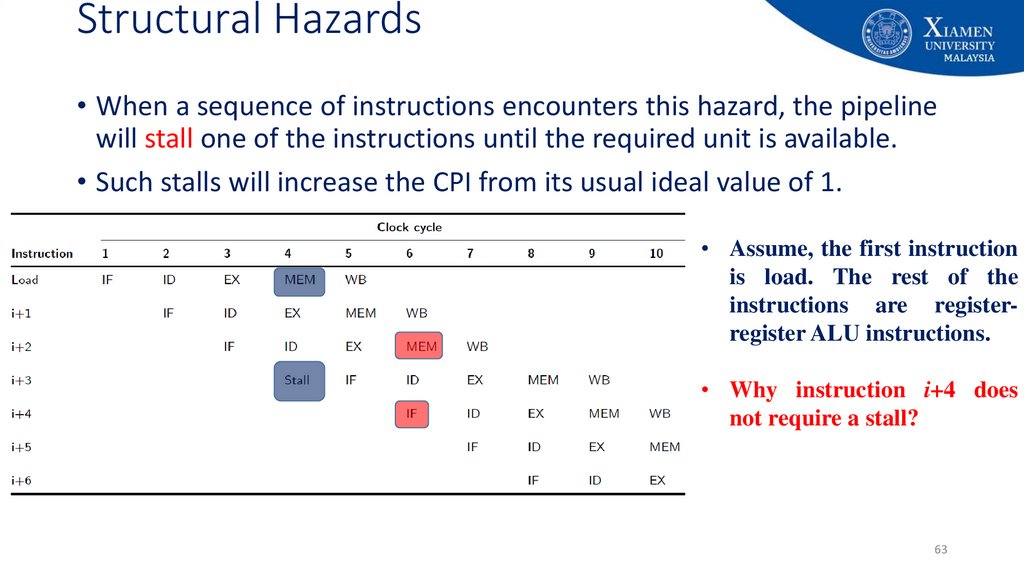

63. Structural Hazards

• When a sequence of instructions encounters this hazard, the pipelinewill stall one of the instructions until the required unit is available.

• Such stalls will increase the CPI from its usual ideal value of 1.

• Assume, the first instruction

is load. The rest of the

instructions are registerregister ALU instructions.

• Why instruction i+4 does

not require a stall?

63

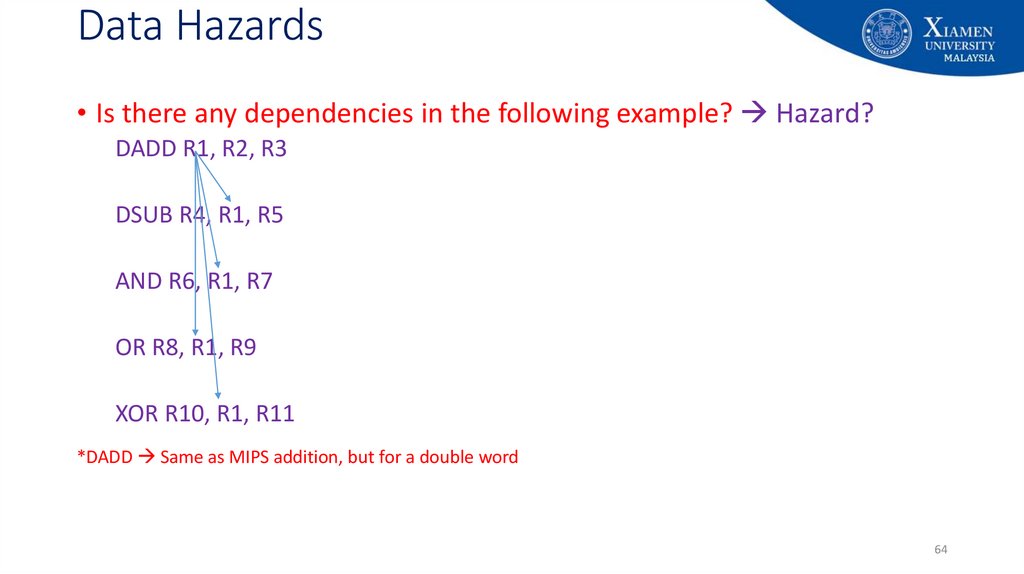

64. Data Hazards

• Is there any dependencies in the following example? Hazard?DADD R1, R2, R3

DSUB R4, R1, R5

AND R6, R1, R7

OR R8, R1, R9

XOR R10, R1, R11

*DADD Same as MIPS addition, but for a double word

64

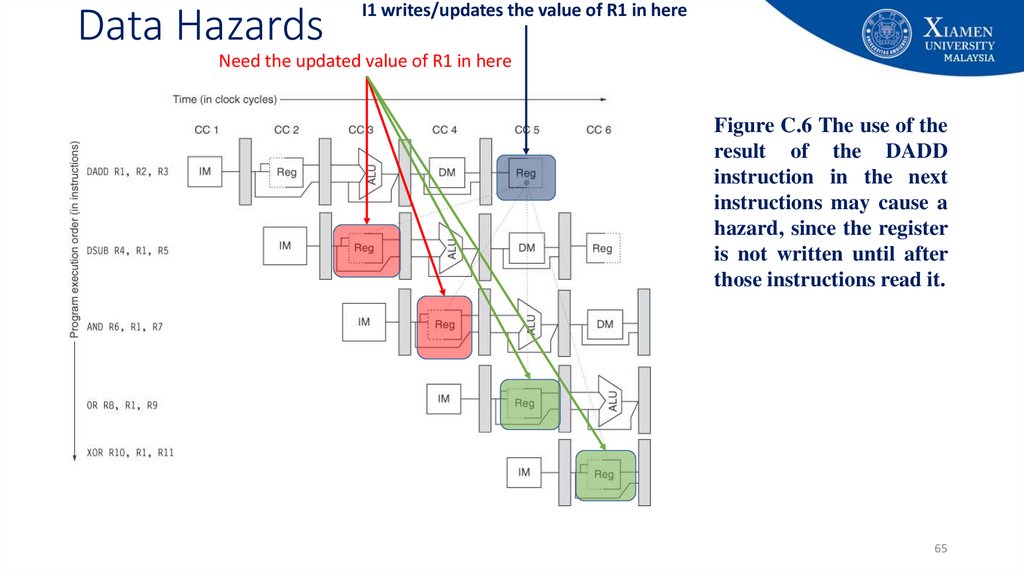

65. Data Hazards

I1 writes/updates the value of R1 in hereNeed the updated value of R1 in here

Figure C.6 The use of the

result of the DADD

instruction in the next

instructions may cause a

hazard, since the register

is not written until after

those instructions read it.

65

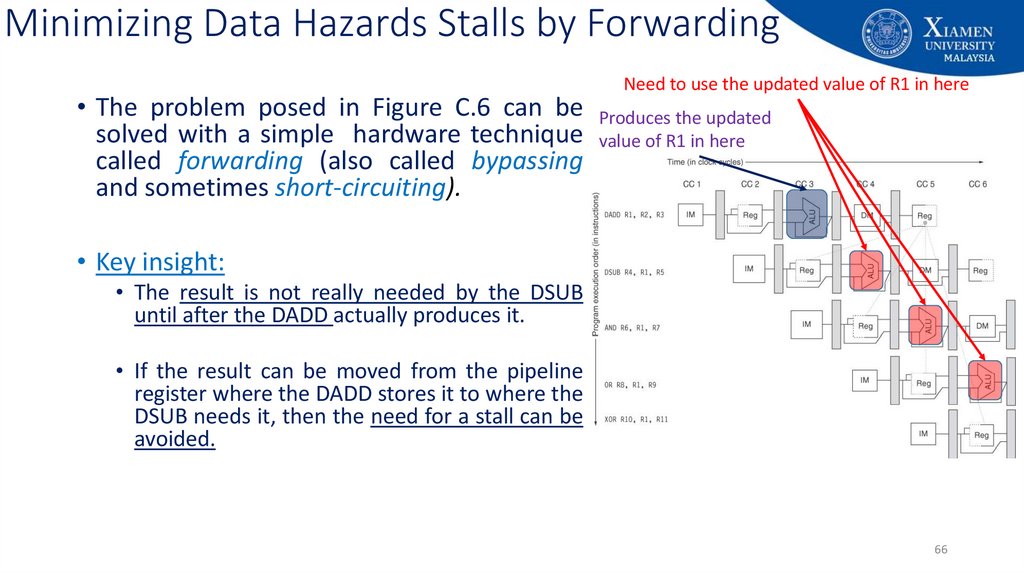

66. Minimizing Data Hazards Stalls by Forwarding

Need to use the updated value of R1 in here• The problem posed in Figure C.6 can be Produces the updated

solved with a simple hardware technique value of R1 in here

called forwarding (also called bypassing

and sometimes short-circuiting).

• Key insight:

• The result is not really needed by the DSUB

until after the DADD actually produces it.

• If the result can be moved from the pipeline

register where the DADD stores it to where the

DSUB needs it, then the need for a stall can be

avoided.

66

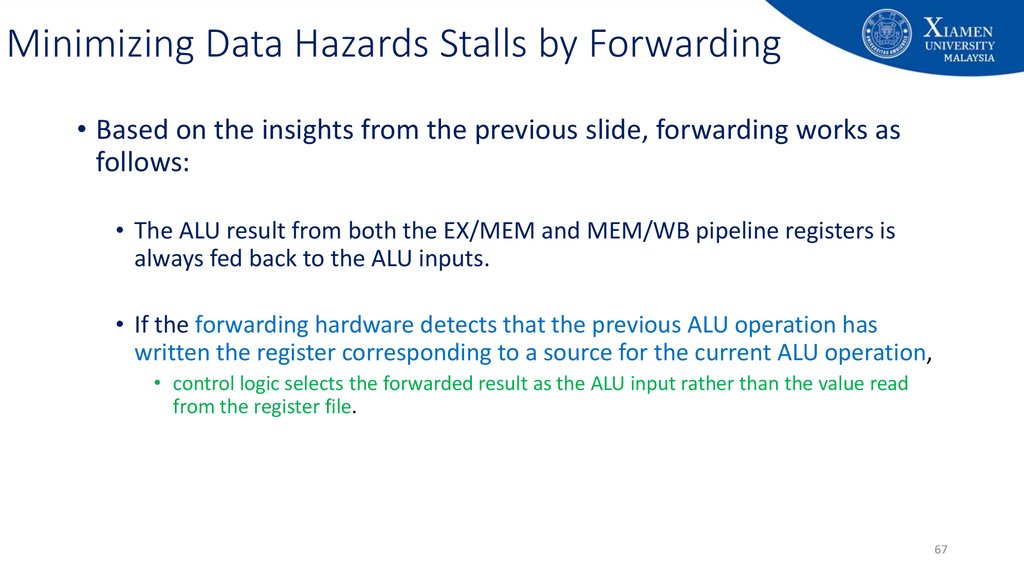

67. Minimizing Data Hazards Stalls by Forwarding

• Based on the insights from the previous slide, forwarding works asfollows:

• The ALU result from both the EX/MEM and MEM/WB pipeline registers is

always fed back to the ALU inputs.

• If the forwarding hardware detects that the previous ALU operation has

written the register corresponding to a source for the current ALU operation,

• control logic selects the forwarded result as the ALU input rather than the value read

from the register file.

67

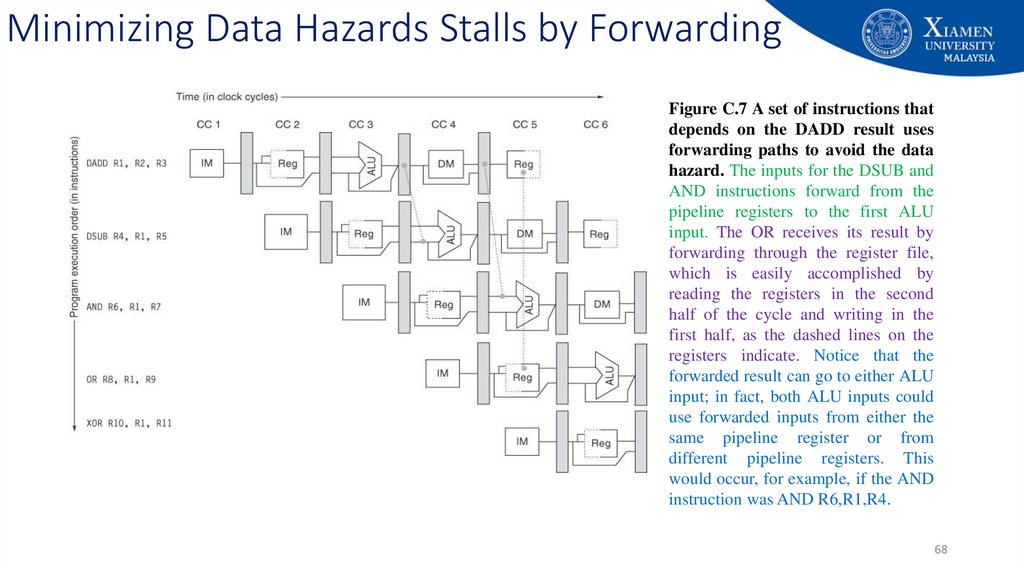

68. Minimizing Data Hazards Stalls by Forwarding

Figure C.7 A set of instructions thatdepends on the DADD result uses

forwarding paths to avoid the data

hazard. The inputs for the DSUB and

AND instructions forward from the

pipeline registers to the first ALU

input. The OR receives its result by

forwarding through the register file,

which is easily accomplished by

reading the registers in the second

half of the cycle and writing in the

first half, as the dashed lines on the

registers indicate. Notice that the

forwarded result can go to either ALU

input; in fact, both ALU inputs could

use forwarded inputs from either the

same pipeline register or from

different pipeline registers. This

would occur, for example, if the AND

instruction was AND R6,R1,R4.

68

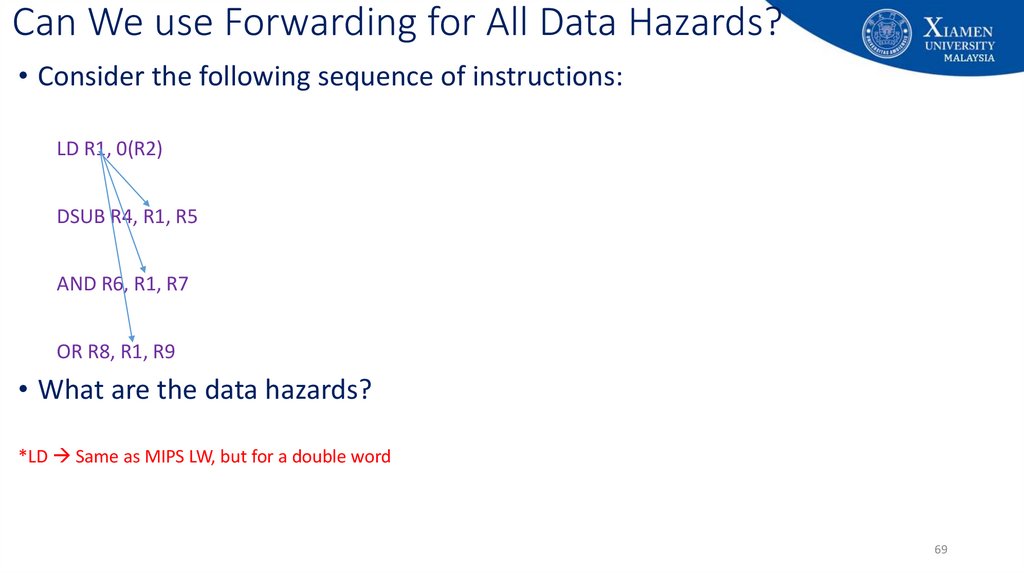

69. Can We use Forwarding for All Data Hazards?

• Consider the following sequence of instructions:LD R1, 0(R2)

DSUB R4, R1, R5

AND R6, R1, R7

OR R8, R1, R9

• What are the data hazards?

*LD Same as MIPS LW, but for a double word

69

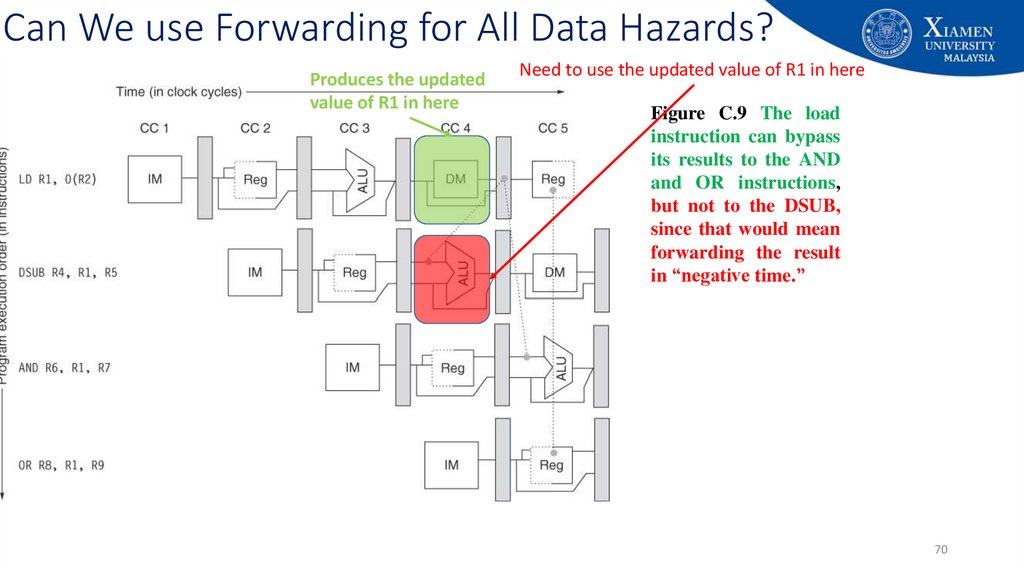

70. Can We use Forwarding for All Data Hazards?

Produces the updatedvalue of R1 in here

Need to use the updated value of R1 in here

Figure C.9 The load

instruction can bypass

its results to the AND

and OR instructions,

but not to the DSUB,

since that would mean

forwarding the result

in “negative time.”

70

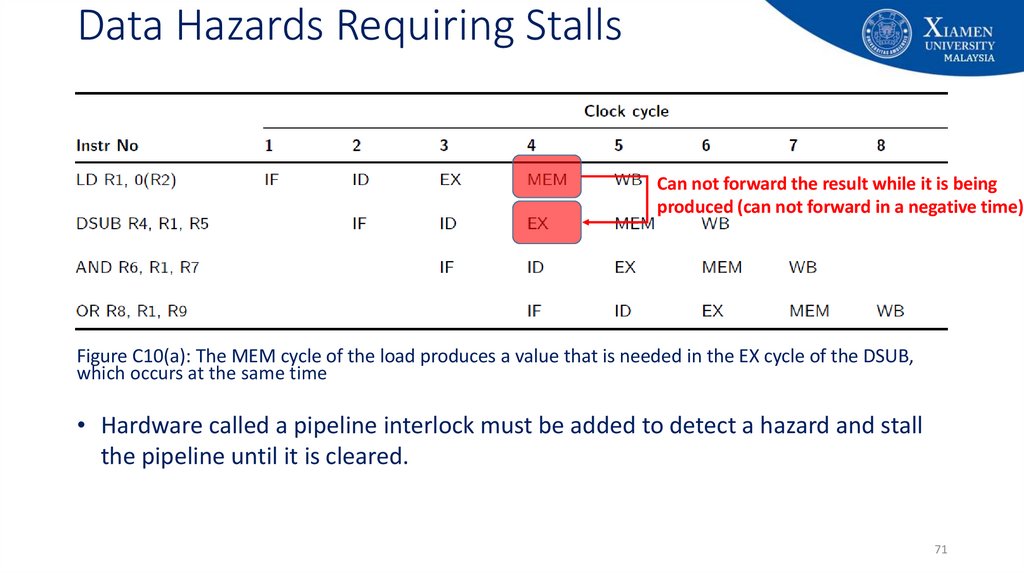

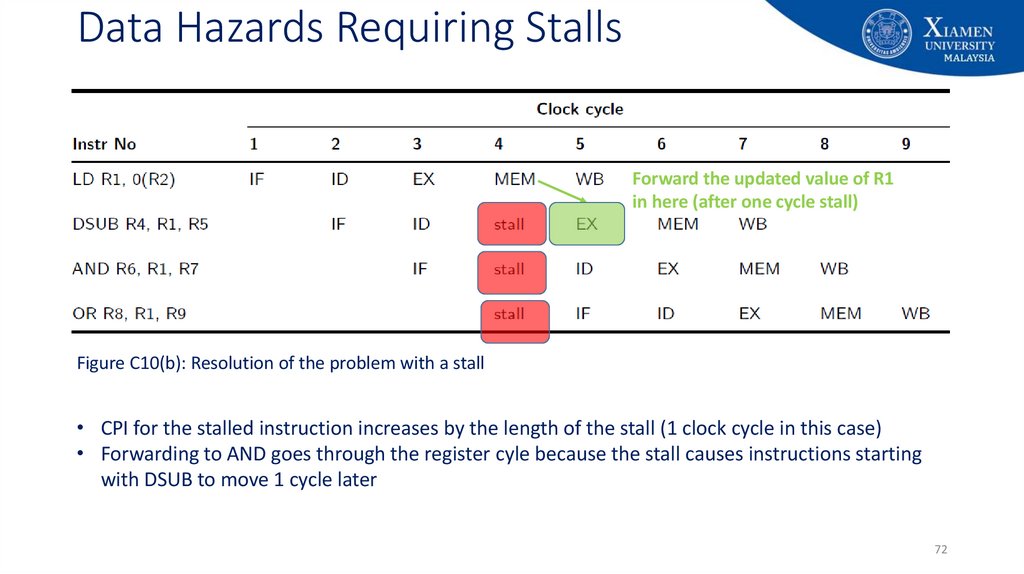

71. Data Hazards Requiring Stalls

Can not forward the result while it is beingproduced (can not forward in a negative time)

Figure C10(a): The MEM cycle of the load produces a value that is needed in the EX cycle of the DSUB,

which occurs at the same time

• Hardware called a pipeline interlock must be added to detect a hazard and stall

the pipeline until it is cleared.

71

72. Data Hazards Requiring Stalls

Forward the updated value of R1in here (after one cycle stall)

Figure C10(b): Resolution of the problem with a stall

• CPI for the stalled instruction increases by the length of the stall (1 clock cycle in this case)

• Forwarding to AND goes through the register cyle because the stall causes instructions starting

with DSUB to move 1 cycle later

72

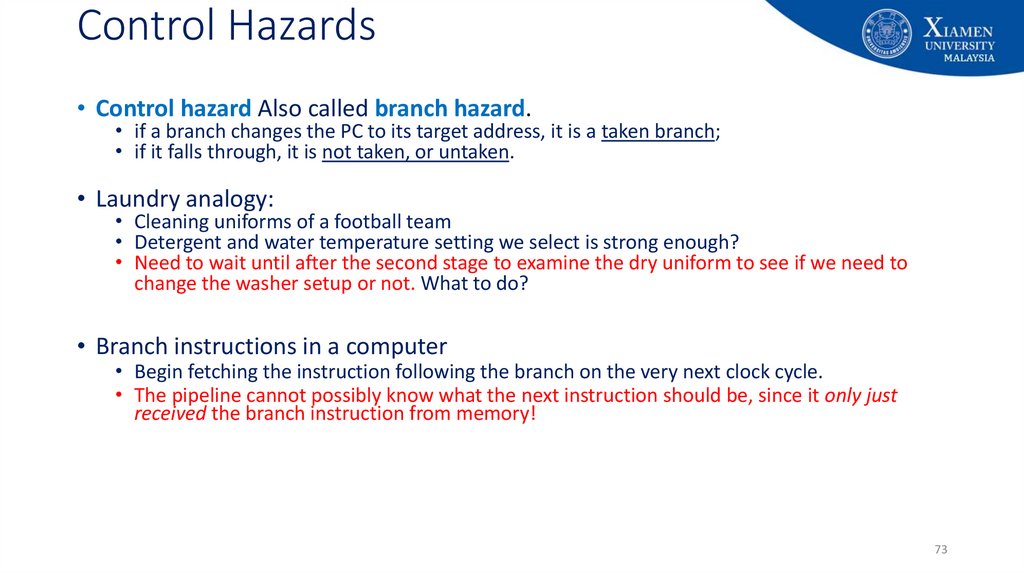

73. Control Hazards

• Control hazard Also called branch hazard.• if a branch changes the PC to its target address, it is a taken branch;

• if it falls through, it is not taken, or untaken.

• Laundry analogy:

• Cleaning uniforms of a football team

• Detergent and water temperature setting we select is strong enough?

• Need to wait until after the second stage to examine the dry uniform to see if we need to

change the washer setup or not. What to do?

• Branch instructions in a computer

• Begin fetching the instruction following the branch on the very next clock cycle.

• The pipeline cannot possibly know what the next instruction should be, since it only just

received the branch instruction from memory!

73

74. Reducing Pipeline Branch Penalties

• We discuss four simple compile time schemes here:• Freeze or Flush (Stall)

• Predicted-not-taken or predicted-untaken

• Predicted-taken

• Delayed branch

74

75. Control Hazards

• Solution 1 – Stall: Just operate sequentially until the first batch is dry and then repeatuntil you have the right formula.

• Just as with laundry, one possible solution is to stall immediately after we fetch a branch,

waiting until the pipeline determines the outcome of the branch and knows what

instruction address to fetch from.

MIPS pipeline knows the

outcome of the branch at ID

stage

Which instruction

to fetch in this

cycle?

Delay/ stall the

pipeline until

resolved

75

76. Control Hazards

• Solution 2 – Predict: If you’re pretty sure you have the right formulato wash uniforms, then just predict that it will work and wash the

second load while waiting for the first load to dry.

• Computers do indeed use prediction to handle branches. One simple

approach is to predict always that branches will be untaken.

• When you’re right, the pipeline proceeds at full speed.

• Only when branches are taken does the pipeline stall.

76

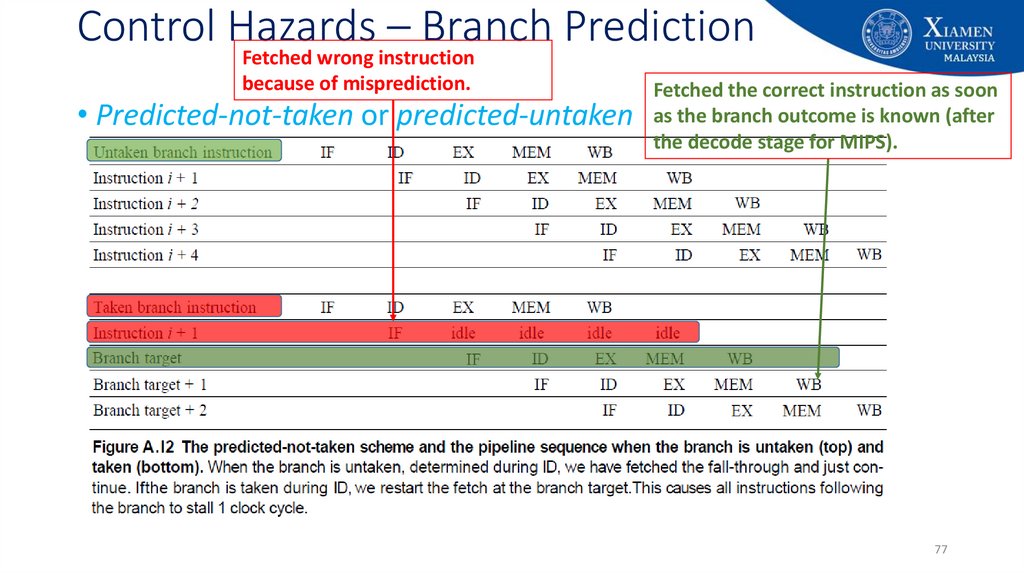

77. Control Hazards – Branch Prediction

Fetched wrong instructionbecause of misprediction.

• Predicted-not-taken or predicted-untaken

Fetched the correct instruction as soon

as the branch outcome is known (after

the decode stage for MIPS).

77

78. Control Hazards – Branch Prediction

• Predicted-taken• An alternative scheme is to treat every branch as taken

The branch predicts that it will be taken, but to fetch the

branch target we need to know what is the target

address! And the target address is known in the decode

stage, where we also know the branch outcome.

• As soon as the branch is decoded and the target address is computed, we assume the branch

to be taken and begin fetching and executing at the target

• Any advantages of predicted taken for MIPS?

• Because in our five-stage pipeline we don't know the target address any earlier than we know

the branch outcome, there is no advantage in this approach for this pipeline.

• In some processors the branch target is known before the branch outcome, and a predictedtaken scheme might make sense.

??

78

79. Other types of Branch Prediction

• A more sophisticated version of branch prediction would have somebranches predicted as taken and some as untaken.

• Laundry analogy:

• the dark or home uniforms might take one formula while the light or road

uniforms might take another.

• In the case of programming,

• at the bottom of loops are branches that jump back to the top of the loop.

Since they are likely to be taken and they branch backward, we could always

predict taken for branches that jump to an earlier address

79

80. Control Hazards – Delayed Decisions

• Laundry analogy:• Place a load of non-football clothes in the washer while waiting for football

uniforms to dry.

• delayed branch

• used by the MIPS architecture

• always executes the next sequential instruction

• with the branch taking place after that one instruction delay

80

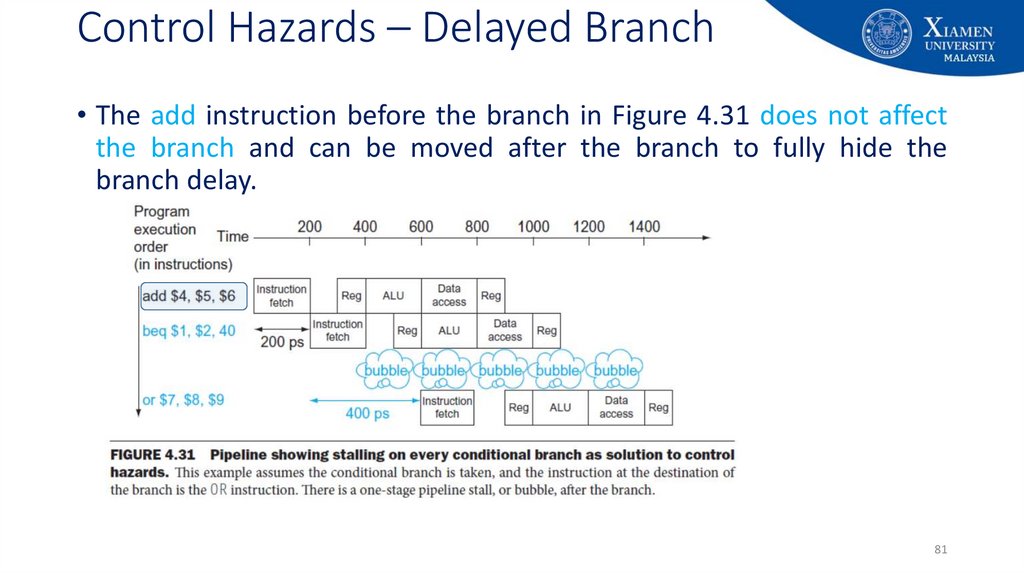

81. Control Hazards – Delayed Branch

• The add instruction before the branch in Figure 4.31 does not affectthe branch and can be moved after the branch to fully hide the

branch delay.

81

82. Control Hazards – Delayed Branch

• Delayed branch – A delayed branch always executes the followinginstruction, but the second instruction following the branch will be affected

by the branch.

• Branch delay slot – The slot directly after a delayed branch instruction,

which in the MIPS architecture is filled by an instruction that does not

affect the branch.

If branch taken, execution is:

Branch instruction

Branch delay instruction

Branch target

(depending on the outcome

of the decoding stage)

If branch not taken, execution is:

Branch instruction

Branch delay instruction

Next Instruction after branch

(depending on the outcome of

the decoding stage)

82

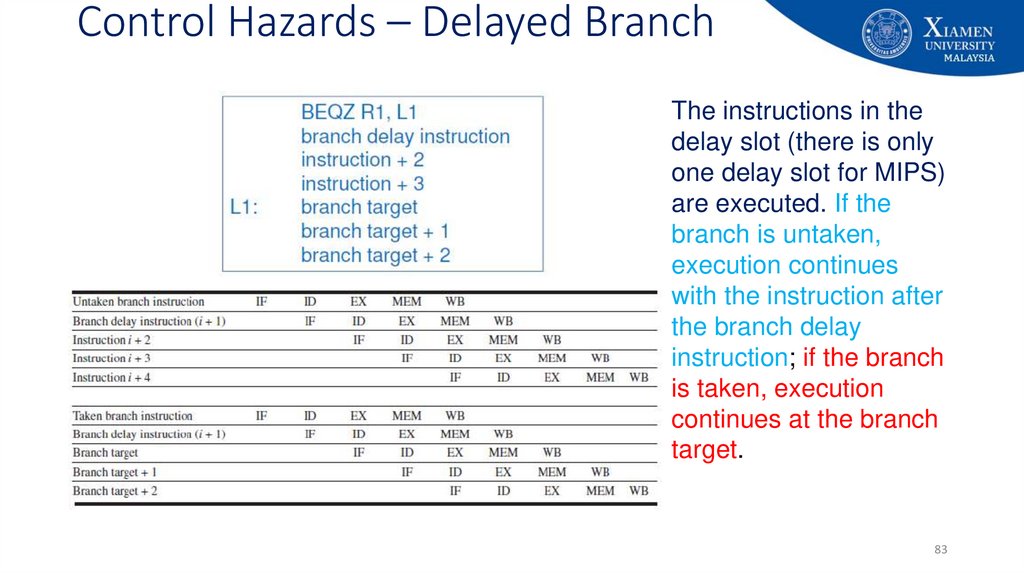

83. Control Hazards – Delayed Branch

The instructions in thedelay slot (there is only

one delay slot for MIPS)

are executed. If the

branch is untaken,

execution continues

with the instruction after

the branch delay

instruction; if the branch

is taken, execution

continues at the branch

target.

83

84. Reducing the Branch Cost through Prediction

• As pipeline gets deeper and potential penalty of branches increases,using delayed branches and similar schemes becomes insufficient.

• Requires more aggressive means:

• Static branch prediction

• Dynamic branch prediction

84

85. Integrated Circuit (IC)

8586. Now we can define Computer Architecture?

• What is computer architecture?• Computer architecture is the organisation of the components which

make up a computer system and the meaning of the operations which

guide its function.

• It defines what is seen on the machine interface, which is targeted by

programming languages and their compilers.

86

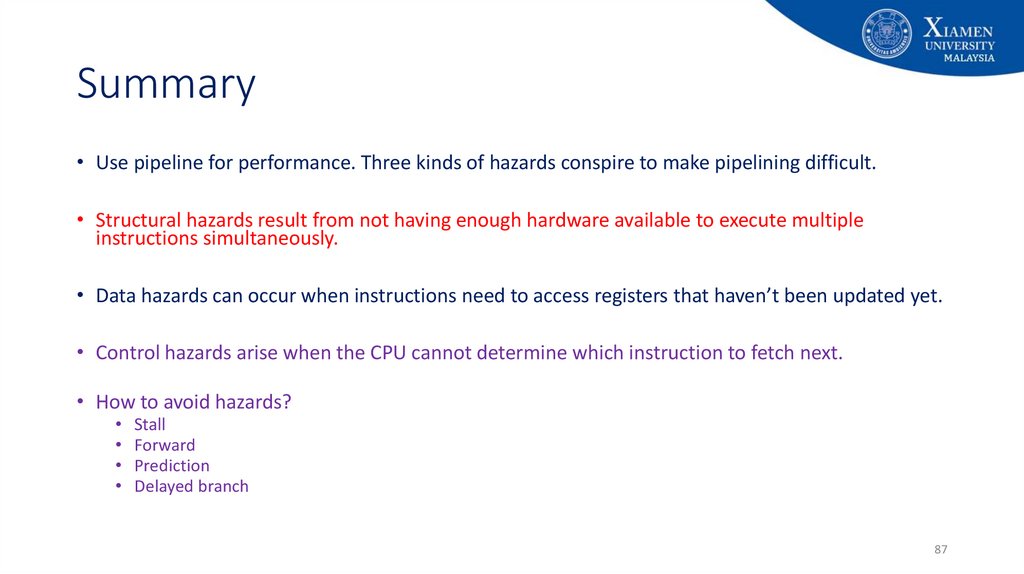

87. Summary

• Use pipeline for performance. Three kinds of hazards conspire to make pipelining difficult.• Structural hazards result from not having enough hardware available to execute multiple

instructions simultaneously.

• Data hazards can occur when instructions need to access registers that haven’t been updated yet.

• Control hazards arise when the CPU cannot determine which instruction to fetch next.

• How to avoid hazards?

Stall

Forward

Prediction

Delayed branch

87

88.

Appendix: University's vision and missionVision

Xiamen University Malaysia aspires to become a university with a

distinct global outlook, featuring first-class teaching and research, and

embracing cultural diversity.

Mission

To nurture young talents with dignity and wisdom, turning them into

fine citizens of the region who will contribute to the prosperity of the

people and social progress of Malaysia, China and Southeast Asia.

88

informatics

informatics