Similar presentations:

Pediatric HSV Epithelial Keratitis

1. Pediartic HSV Epithelial Keratitis

2.

3.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis is an important cause of ocular morbidity thatcan cause

significant vision loss due to its recurring nature. It is caused by the same 2 closely

related viruses:

herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2).

HSV-1 is the first

member of the human herpes viruses (HHV-1) belonging to the subfamily

Alphaherpesviridae. At

least 80% of the world’s population has been exposed to HSV-1.

Children with HSV keratitis pose a unique challenge to the clinician. The most

serious concern in children is that they are susceptible to amblyopia (lazy eye) from

corneal scarring that may

occur. The virus is transmitted from human to human via secreted fluids and close

contact with

mucosal surfaces or abraded skin. Initial infection is usually asymptomatic and

occurs in children

younger than 5 years old. In cases of HSV-2, it is transmitted as the newborn

passes through an

infected birth canal. Ocular infection may occur directly through droplet spread or

indirectly via

neuronal spread from a nonocular site such as the oral mucosa.

4.

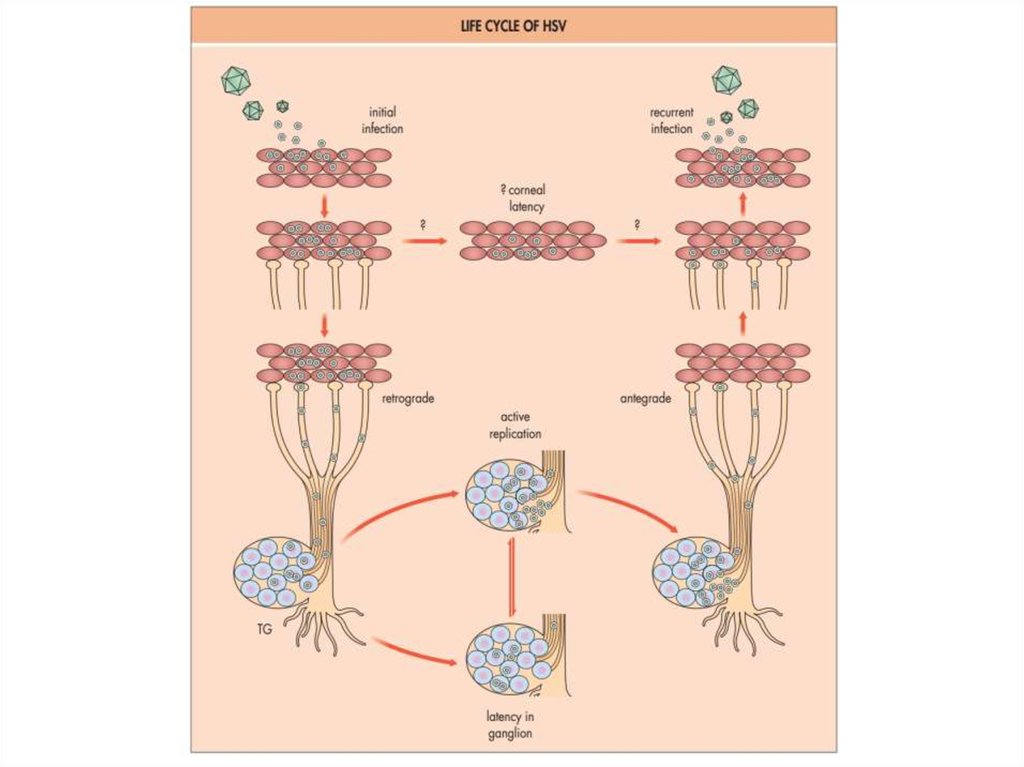

HSV keratitis occurs when the infection reaches the cornealepithelium and stroma of the cornea. Manifestations can include

cutaneous vesicles, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis

(corneal dendritic ulcers), and stromal keratitis. Nonspecific

signs of primary herpetic corneal

infection include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. When

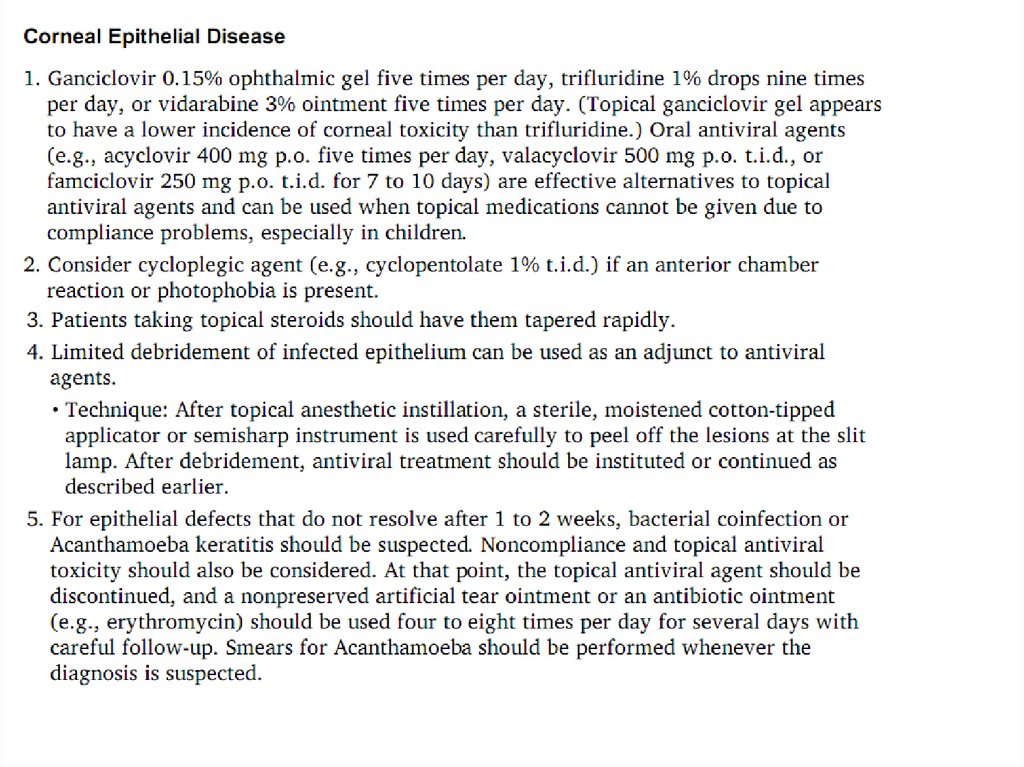

the virus gains access to the central

nervous system, the virus becomes latent in the trigeminal

ganglia (HSV-1 or varicella–zoster

virus [VZV]) or in the spinal ganglia (HSV-2). Recurrent attacks

occur when the virus travels

peripherally via sensory nerves to infect target tissues in the

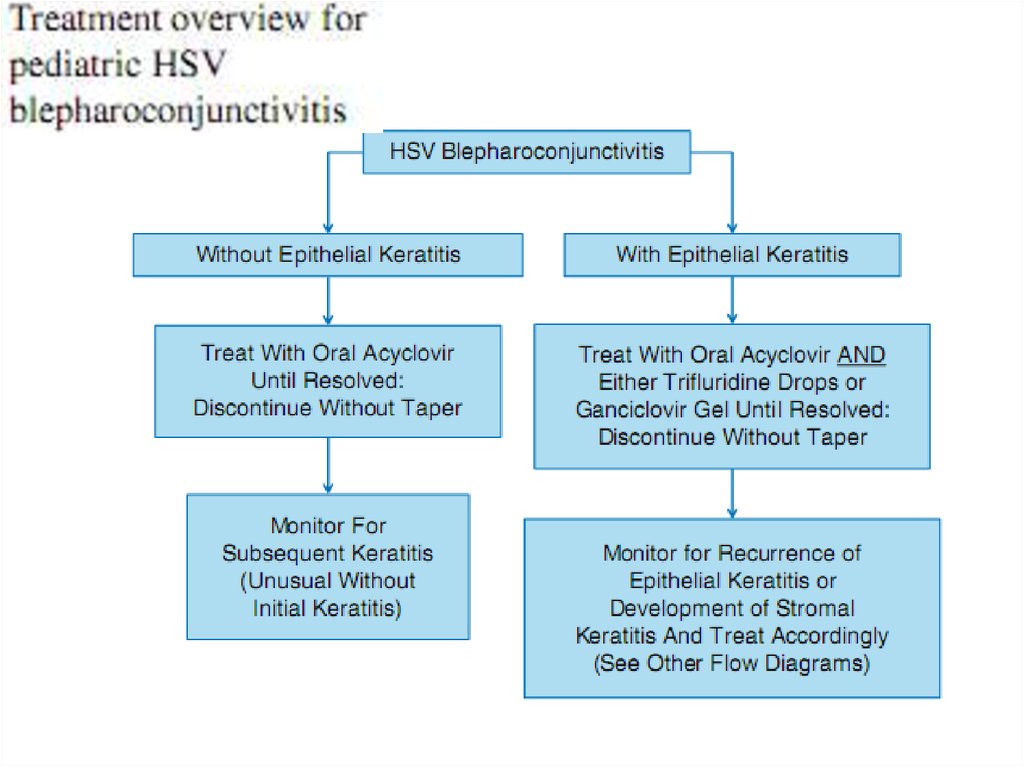

eye. These attacks may be triggered

by any of the following stressors: fever, ultraviolet light

exposure, trauma, stress, menses, and

immunosuppression.

5.

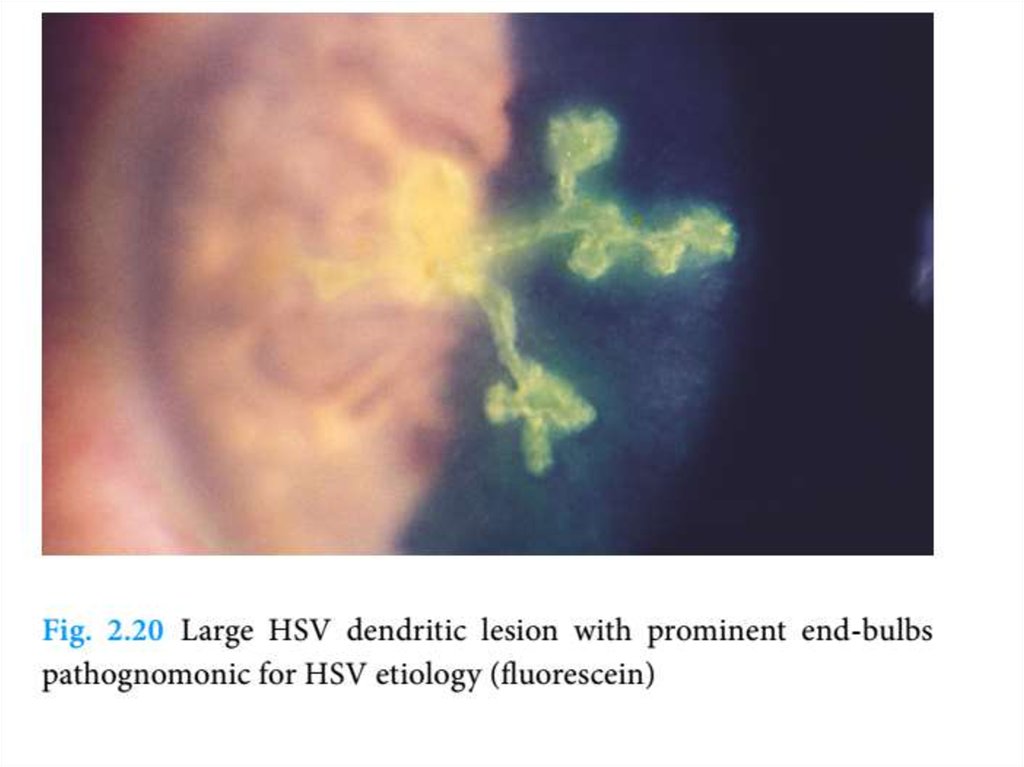

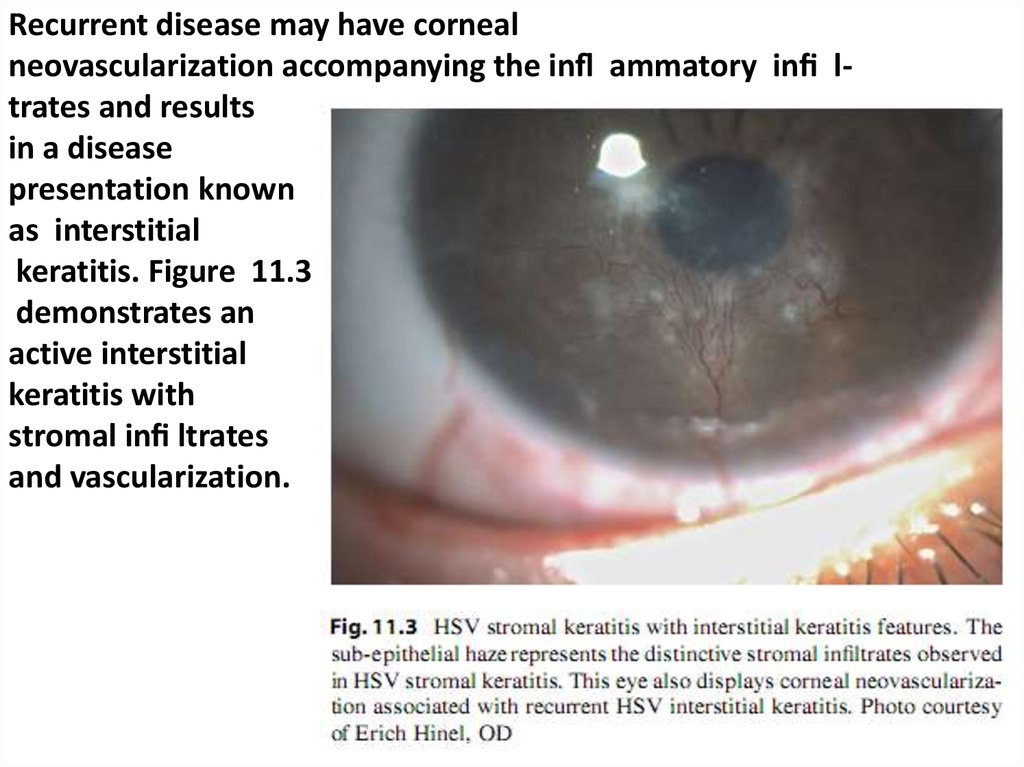

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infection and inflammation eventuallycause corneal scarring, thinning, neovascularization, and

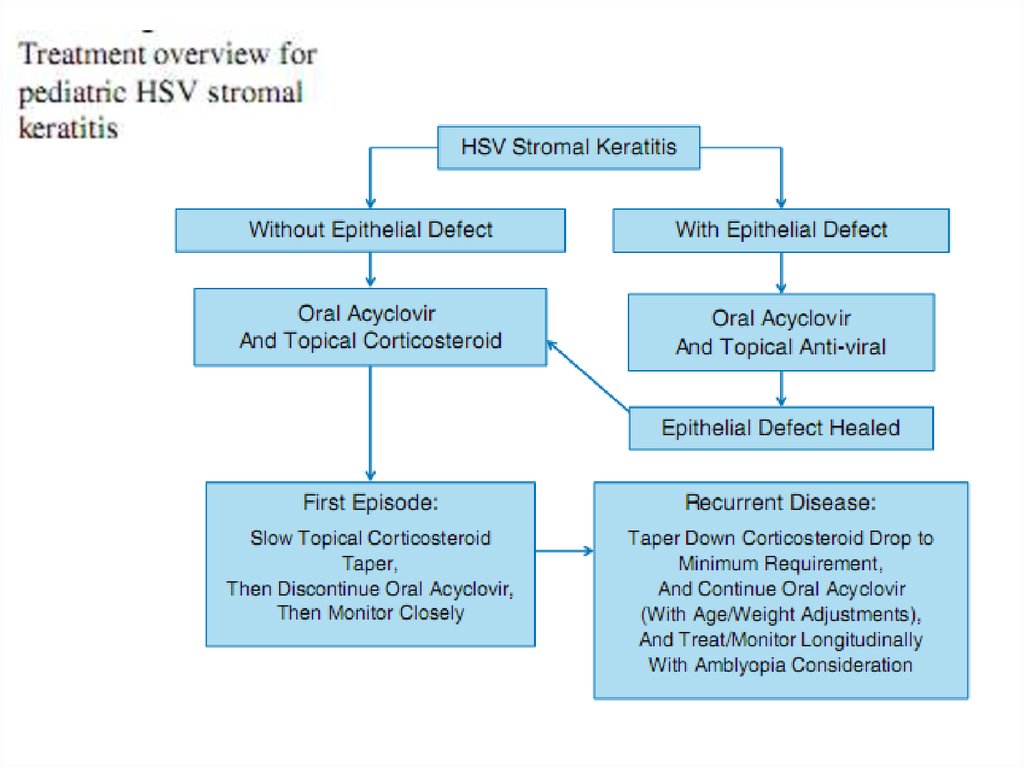

stromal keratitis. This disease usually occurs unilaterally, but

bilateral infection, although not frequently seen, usually afflicts a

younger age group and can be

more severe. The corneal dendrites of herpes simplex infections are

epithelial ulcers whose edges

stain brightly with fluorescein and have terminal bulbs (Figure 19-1).

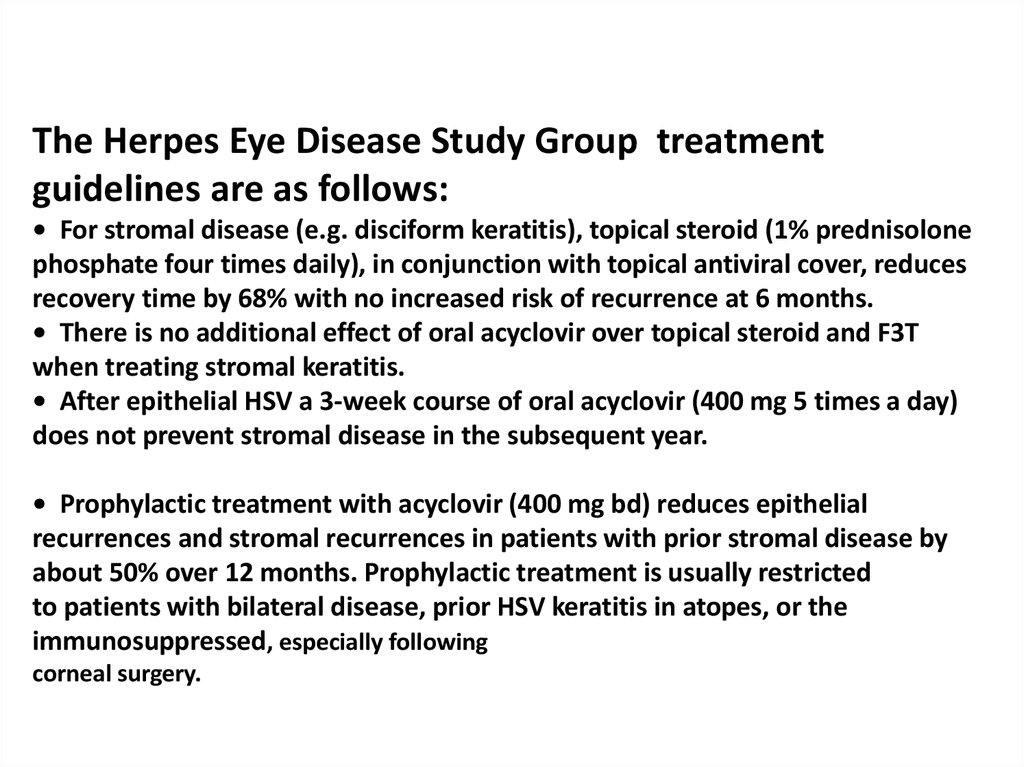

Herpes zoster dendrites

are raised lesions, do not have terminal bulbs, and do not stain well

with fluorescein. Some ophthalmic findings of HSV keratitis are not

directly caused by the viral infection itself, but instead

relate to the immunologic response to the infection, such as chronic

keratouveitis (inflammation

within the anterior chamber of the eye) and disciform and necrotizing

keratitis (cornea is filled

with inflammatory cells and has neovascularization despite an intact

surface).

6.

HSV keratitis in children may differ from that in adults. The rate ofbilateral involvement in

the largest series of infected children was 10% to 26%, which is

higher than seen in adults. The

Herpetic Eye Disease Study estimated that both epithelial and

stromal keratitis recurred in 18%

of patients during a follow-up period of 18 months. Age, sex,

ethnicity, and nonocular herpes were

not significantly associated with recurrences. However, the Herpetic

Eye Disease Study was limited to patients 12 years or older. In

different series of pediatric herpetic viral keratitis, recurrence

rates ranged from 33% to 80%. Corneal scarring and ulcerations

from recurrent herpetic keratitis

can be visually debilitating and potentially necessitate surgical

intervention with penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplantation)

or tarsorrhaphy (partial lid closure). The inflammatory response

from herpetic keratitis leads to stromal scarring and opacification

and tends to be more severe

in children than adults. For younger children, especially under age

8, the corneal opacity and

irregular astigmatism induced by the scars lead to visual deprivation

and loss of vision. Even with

antiviral therapy, corneal healing can take up to 1 month and will

require continued ophthalmic

care due to residual corneal scarring and risk of vision loss.

7.

8.

HERPES SIMPLEXVIRUS

PRIMARY HSV INFECTION

Primary HSV ocular infection most commonly manifests as

blepharoconjunctivitis (often with conjunctival ulceration) that heals without

scarring (Fig. 4-15-3). The associated follicular conjunctivitis is often

mistaken for adenoviral conjunctivitis (Fig. 4-15-4); up to a third of

unilateral follicular conjunctivitis may be culture-positive for HSV.13–15

Other features include lid vesicles and conjunctival dendrites. Keratitis

is rare, occurring in only 3–5% of cases, though severe bilateral disease

can occur in atopic or immunocompromised patients.

9.

10.

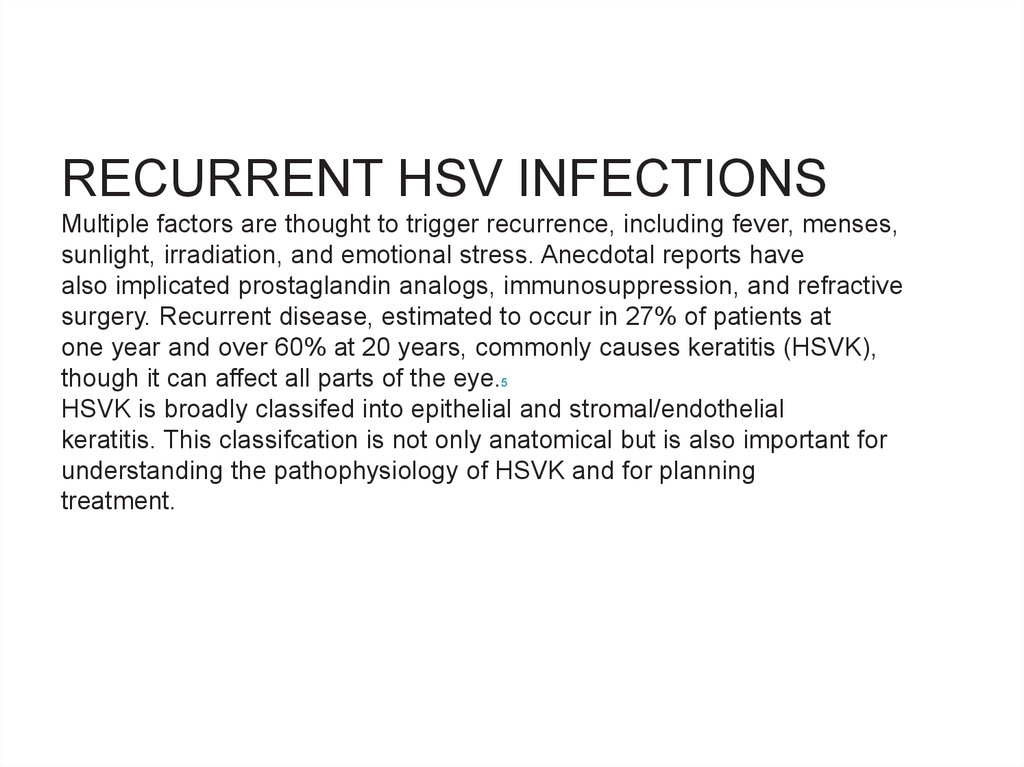

RECURRENT HSV INFECTIONSMultiple factors are thought to trigger recurrence, including fever, menses,

sunlight, irradiation, and emotional stress. Anecdotal reports have

also implicated prostaglandin analogs, immunosuppression, and refractive

surgery. Recurrent disease, estimated to occur in 27% of patients at

one year and over 60% at 20 years, commonly causes keratitis (HSVK),

though it can affect all parts of the eye.5

HSVK is broadly classifed into epithelial and stromal/endothelial

keratitis. This classifcation is not only anatomical but is also important for

understanding the pathophysiology of HSVK and for planning

treatment.

11.

Sunlight, local physical trauma, hormonal changes, andimmunological stress (as by fever) are thought to contribute

to risk of recurrence of non-ocular herpetic disease [ 9 ].

However, with correction for recall bias, the Herpetic Eye

Disease Study (HEDS) Group found that none of these factors were a signi cant cause of recurrent ocular herpes [ 10 ].

However, a history of atopic disease has been associated

with recurrent herpetic eye disease, possibly secondary to

immunologic dysfunction [ 11 – 13 ]. Therefore, the practitioner should inquire about personal and family history of conditions such as asthma, eczema, and seasonal allergies.

12.

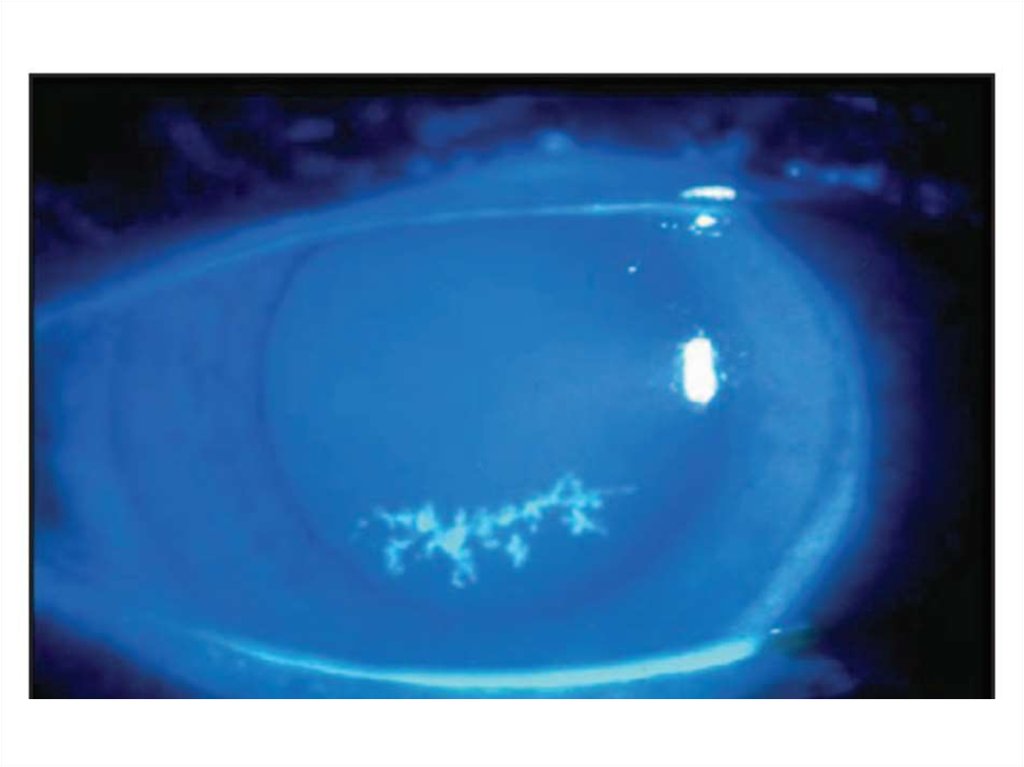

Epithelial ulcers may cause sensitivity to light,blurriness, or a foreign body sensation [ 24 ]. In children,

photophobia is easily observed [ 26 ]. Pediatric HSV

keratitis is typically unilateral; however, atopy and an

altered immune system predispose to bilateral disease [ 7 ].

Diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis is typically based on

clinical ndings. Figure 11.2 shows a typical HSV

dendrite.

The distinctive appearance and staining pattern of these

ulcers are important diagnostic points.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

Fig. 1.17a–d Features of an

HSV dendritic

(branching) fgure, visualized (a)

without staining, (b and c) with

uoresceinsodium, (c and d) in time

sequence, and (d) with rose bengal

dye added. (a) Te fgure consist of

two parts: a central corethat appears

granular (long arrow) and a

surrounding zone (short arrow) (cf.

drawing). (b) Green-stained tear

uid is pooling within the central

core. Te surrounding zone is elevated

(dark). Within this zone, green uid

is pooling between protruding

swollen/rounded cells (dark rounded

dots, arrowhead)

18.

Fig. 1.17 (c) Afer a blink,the stained tear uid

appears more brilliantly

green. As in (b), it is

pooling within the

central core

and between the

protruding

swollen/rounded cells

(arrowhead). So far,

there is no uorescein

di usion into the

elevated surrounding

zone. (d) A few minutes

later, the elevated

surrounding zone is

stained brilliantly green

( uorescein di usion).

Rose

bengal dye reveals

patches of surface

debris within the central

core and a few rounded

dots (arrowhead)

19.

20.

Epithelial herpes simplex keratitis. (A) Stellate lesions; (B) bedof a dendritic ulcer stained with fuorescein;

21.

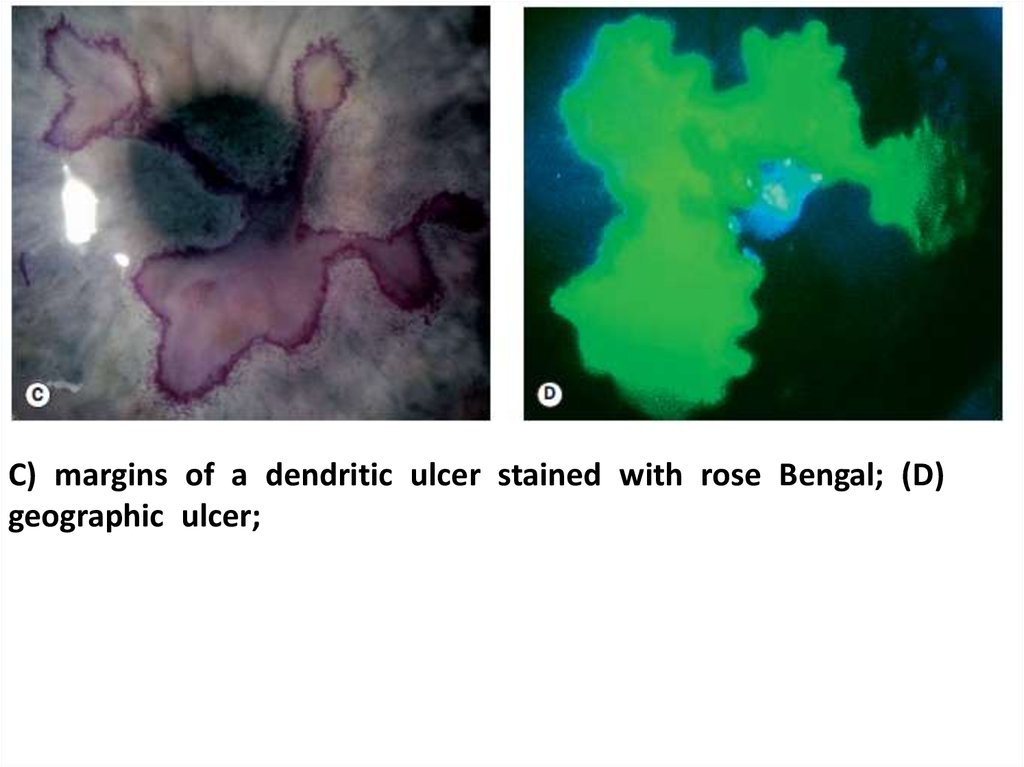

C) margins of a dendritic ulcer stained with rose Bengal; (D)geographic ulcer;

22.

(E) persistent epithelial changes following resolutionof active infection;

(F) residual subepithelial haze

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

In particular, HSVculture and PCR are commonly available testing methods

that can be utilized to aid in the diagnosis of HSV epithelial

keratitis. Serum antibody testing can identify previous HSV

infection. It is important to note that viral samples for lab

testing should be collected prior to epithelial staining

since rose bengal is toxic to HSV [ 29 ]. Collecting samples

prior to staining will thus reduce false negative test results.

29.

A 5-year-old patient with a history of type I diabetes mellituspresented with 7 days of right eye pain, redness, and irritation. She

was diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis by her primary care physician

but did not improve. Slit-lamp examination with uorescein

revealed a dendritic epithelial defect with terminal bulbs

(Fig. 10.3 ), and she

was subsequently

diagnosed with HSV

epithelial keratitis.

Treatment with

400 mg oral acyclovir

suspension 4 times

daily led to

resolution of the

dendrite with only

minimal corneal

scarring.

30.

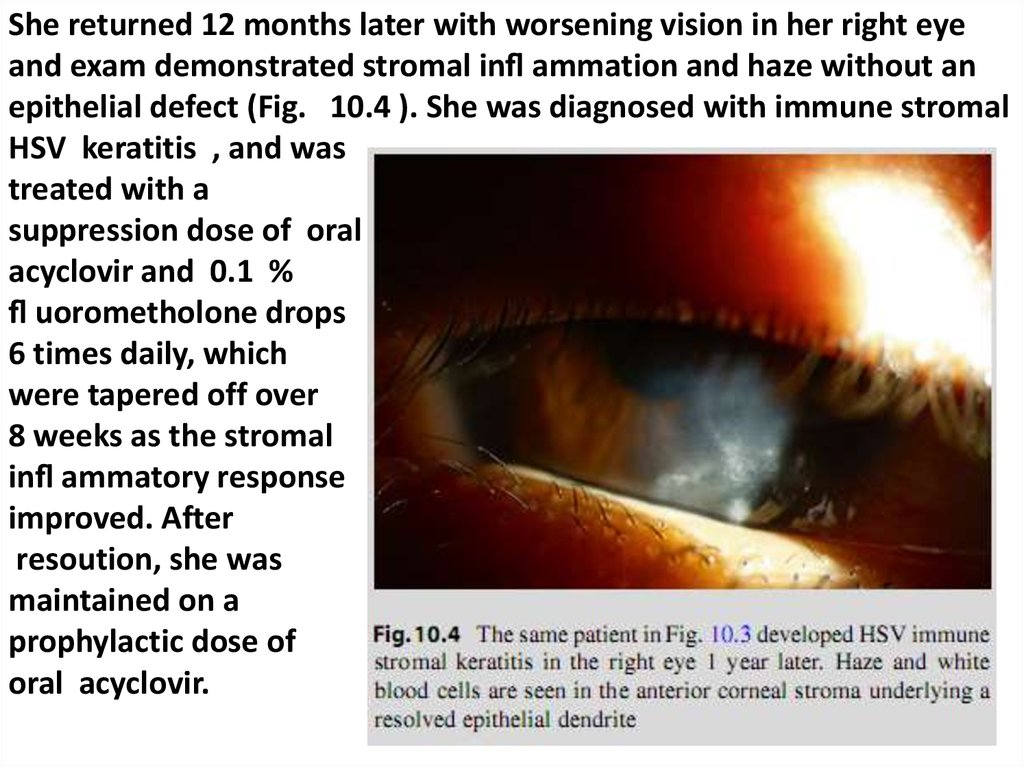

She returned 12 months later with worsening vision in her right eyeand exam demonstrated stromal in ammation and haze without an

epithelial defect (Fig. 10.4 ). She was diagnosed with immune stromal

HSV keratitis , and was

treated with a

suppression dose of oral

acyclovir and 0.1 %

uorometholone drops

6 times daily, which

were tapered off over

8 weeks as the stromal

in ammatory response

improved. After

resoution, she was

maintained on a

prophylactic dose of

oral acyclovir.

31.

Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in somecases without intervention [ 30 ], medication is utilized to speed

resolution,

reduce corneal scarring, and diminish stromal

in ammation. Since the epithelial ulcers are caused by actively

replicating virus, treatment targets the virus itself. Topical

antiviral drugs (tri uridine drops, vidarabine ointment [not

currently commercially available], or ganciclovir gel) have

been shown to be effective in resolving HSV epithelial keratitis. However, instillation of eye drops in small

children may be dif cult, and tear dilution from crying could

prevent an effective dose. Oral acyclovir thus provides an

important adjunctive treatment for pediatric HSV epithelial

keratitis, and may provide effective treatment without the use

of a topical antiviral [ 21 ]. See Table 11.1 for acyclovir dosage

considerations.

32.

33.

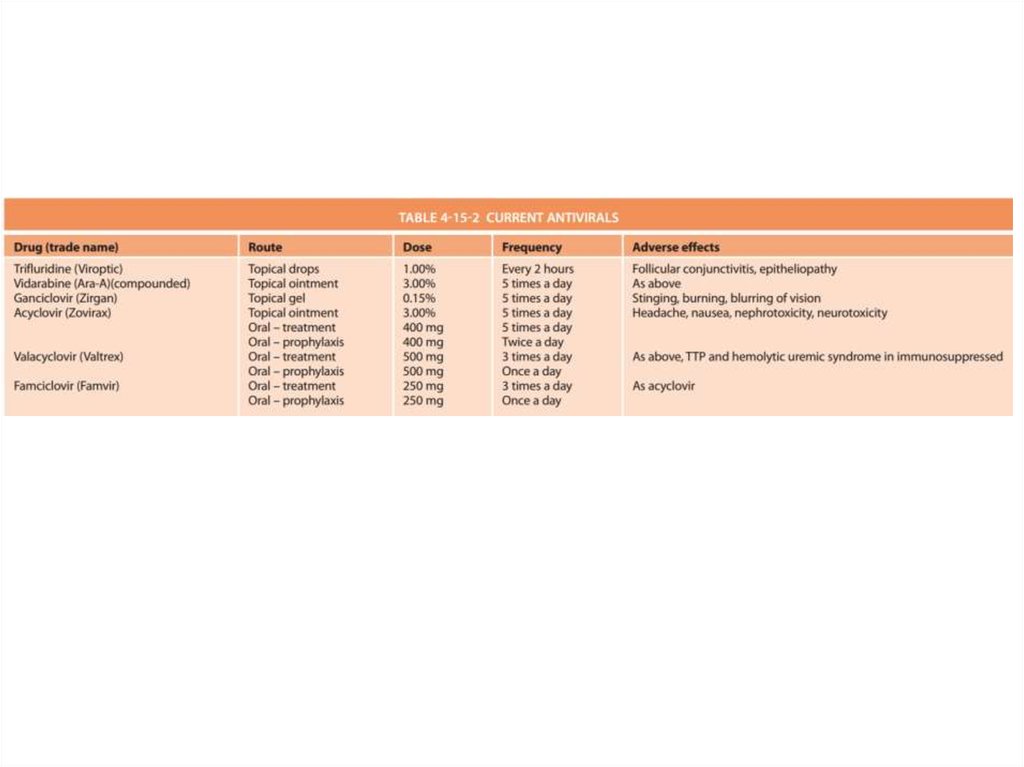

Interestingly, only topical antiviral medication has beenFDA approved for the treatment of HSV keratitis and only

for epithelial keratitis. Evidence-based oral antiviral

treatment protocols have been developed for multiple

forms of ocular HSV disease from retrospective studies as

well as from the prospective studies conducted by the HEDS

Group.

For infectious HSV epithelial keratitis, topical or oral

antivirals are effective. In children, the recommended dose

of oral acyclovir in epithelial keratitis is 12-40 mg/kg/day in

divided doses up to 40 kg, and the adult dose of 400 mg 5

times daily in children greater than 40 kg [2].

34.

35.

Epithelial HSV disease (dendritic ulcer, geographic ulcer)is the result of viral replication, and is treated with a

topical antiviral agent (Table 15.9). Oral antiviral and

topical corticosteroid is not required.

Oral acyclovir did not hasten

healing of epithelial disease when used in combination with

topical treatment.

36.

Topical corticosteroids are not indicated forHSV epithelial keratitis and may in fact accelerate ulceration

[ 24 ]. However, topical corticosteroids play a role in the treatment of HSV stromal keratitis. Stromal keratitis is discussed

in the next section. Some clinicians recommend debridement

of infected epithelial cells to enhance resolution. Historically,

corneal debridement has been described as a method to reduce

the amount of active virus in the epithelium. However, debridement may be less effective than antiviral therapy and may not

signi cantly improve outcome of antiviral therapy [ 32 ].

Additionally, corneal debridement is dif cult in children, and

may increase discomfort.

37.

Unfortunately, as described in the introduction,HSV epithelial keratitis can recur. After an epithelial ulcer resolves, a

faint stromal scar may remain. Recurrent HSV dendritic

ulcers may recur near the scar. Epithelial recurrences increase

the risk of HSV stromal keratitis, an immune-mediated disease process. Recurrence of HSV keratitis is higher in children and is a major management concern [ 21 ]. Thus,

monitoring of children with periodic follow-up examinations

and educating the parents for signs of recurrence are essential.

38.

39.

40.

41.

HSV stromal keratitis classically involves an immunemediated response to inactive HSV antigen in the cornealstroma [ 6 ]. However, complex presentations with mixed patterns of anterior corneal disease and corneal scarring from

multiple recurrences are possible [ 24 ]. Simple HSV stromal

keratitis may present with single or multifocal sub-epithelial

in ammatory in ltrates.

42.

Recurrent disease may have cornealneovascularization accompanying the in ammatory in ltrates and results

in a disease

presentation known

as interstitial

keratitis. Figure 11.3

demonstrates an

active interstitial

keratitis with

stromal in ltrates

and vascularization.

43.

Treatment ofstromal keratitis in children typically involves the use of topical corticosteroids and oral antivirals. The topical corticosteroid is necessary to treat the stromal in ammation, and the

oral antiviral treats any active viral disease in addition to a

putative contribution in preventing recurrence

44.

The topical corticosteroid may be tapered and the oral antiviraldiscontinued after the rst episode. However, longitudinal

treatment throughout the amblyogenic period may be required

to prevent visually debilitating scarring in the visual axis and

resultant amblyopia. Corticosteroid should be tapered to the

minimum amount necessary to control in ammation.

45.

Valacyclovir may be considered forolder teenage patients with HSV stromal keratitis since it has

been FDA approved for long-term treatment (at the 1 g/day

suppressive therapy dose for genital herpes) [ 33 ]. Valacyclovir

is a pro-drug of acyclovir that has an ester moiety that is

removed by esterases to result in the active acyclovir. As a

pro-drug of acyclovir, valacyclovir has greater bioavailability

and would theoretically be expected to have a similar side

effect pro le. Famciclovir has also been approved for longterm suppressive therapy of genital herpes (at 250 mg twice a

day), so it may also be considered for HSV stromal keratitis

in older teenage patients [ 34 ]. However, famciclovir is not

FDA approved for children.

46.

Epithelial keratitis later followed bystromal keratitis or concomitant epithelial

disease.

In cases with concomitant epithelial

disease, topical treatment is generally added

for the rst 2 weeks.

47.

48.

49.

The Herpes Eye Disease Study Group treatmentguidelines are as follows:

• For stromal disease (e.g. disciform keratitis), topical steroid (1% prednisolone

phosphate four times daily), in conjunction with topical antiviral cover, reduces

recovery time by 68% with no increased risk of recurrence at 6 months.

• There is no additional effect of oral acyclovir over topical steroid and F3T

when treating stromal keratitis.

• After epithelial HSV a 3-week course of oral acyclovir (400 mg 5 times a day)

does not prevent stromal disease in the subsequent year.

• Prophylactic treatment with acyclovir (400 mg bd) reduces epithelial

recurrences and stromal recurrences in patients with prior stromal disease by

about 50% over 12 months. Prophylactic treatment is usually restricted

to patients with bilateral disease, prior HSV keratitis in atopes, or the

immunosuppressed, especially following

corneal surgery.

50.

51.

Typical features of a neonatal HSV infection include localizedexternal lesions (skin, eye, and/or mouth), disseminated

herpes affecting internal organs, and central nervous system

infection (encephalitis). An infected infant may display several of these features. Ocular herpes in the newborn typically

appears as periorbital skin vesicles, blepharoconjunctivitis,

keratitis, anterior uveitis, chorioretinitis, and congenital cataracts [ 3 , 39 ]. Importantly, a dilated fundus examination

should be performed in any neonate with suspected HSV

infection. Since herpes infections may resemble other neonatal infections, laboratory tests (e.g., uorescein antibody tests,

herpes culture, or PCR testing) should be performed in all

cases of suspected neonatal herpes [ 28 ]. While awaiting lab

results, the newborn should be empirically treated with intravenous acyclovir.

52.

Overall prognosis of neonatal ocular HSV infectiontreated with intravenous antiviral therapy is generally good.

However, mortality is higher in newborns with disseminated

infection or CNS disease [ 28 ]. Visual outcome is poorer

when corneal herpetic disease causes scarring. Infants must

also be monitored closely for evidence of recurrent disease.

Infants with recurrent HSV keratitis are typically followed

longitudinally by an infectious disease specialist.

Additionally, longitudinal follow-up by a

pediatric ophthalmologist is important due to the risk of amblyopia development associated with recurrent HSV keratitis. If there is

recurrent neonatal ocular HSV infection, higher oral doses of

acyclovir may be necessary.

medicine

medicine