Similar presentations:

Lecture6

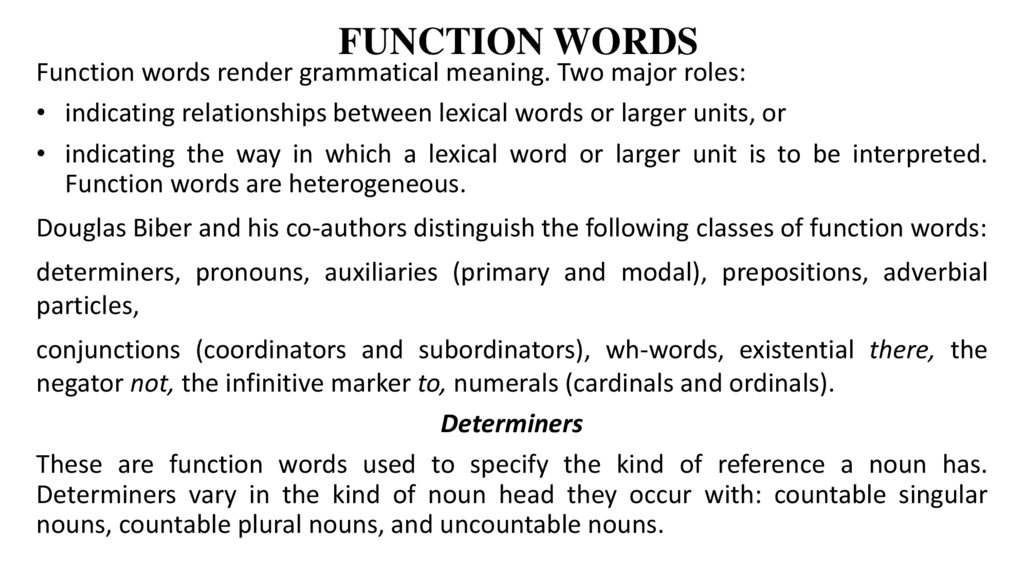

1. FUNCTION WORDS

Function words render grammatical meaning. Two major roles:• indicating relationships between lexical words or larger units, or

• indicating the way in which a lexical word or larger unit is to be interpreted.

Function words are heterogeneous.

Douglas Biber and his co-authors distinguish the following classes of function words:

determiners, pronouns, auxiliaries (primary and modal), prepositions, adverbial

particles,

conjunctions (coordinators and subordinators), wh-words, existential there, the

negator not, the infinitive marker to, numerals (cardinals and ordinals).

Determiners

These are function words used to specify the kind of reference a noun has.

Determiners vary in the kind of noun head they occur with: countable singular

nouns, countable plural nouns, and uncountable nouns.

2.

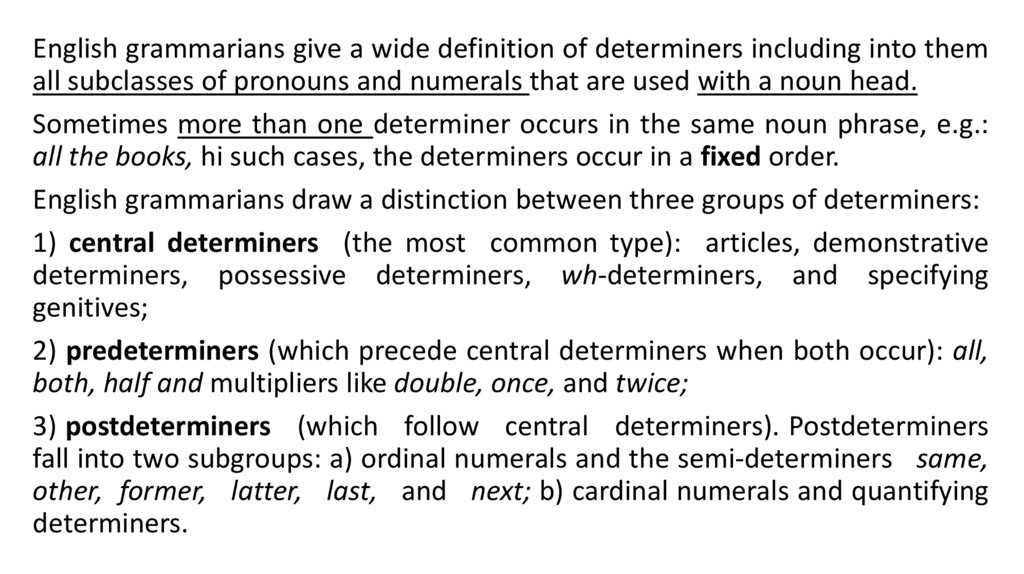

English grammarians give a wide definition of determiners including into themall subclasses of pronouns and numerals that are used with a noun head.

Sometimes more than one determiner occurs in the same noun phrase, e.g.:

all the books, hi such cases, the determiners occur in a fixed order.

English grammarians draw a distinction between three groups of determiners:

1) central determiners (the most common type): articles, demonstrative

determiners, possessive determiners, wh-determiners, and specifying

genitives;

2) predeterminers (which precede central determiners when both occur): all,

both, half and multipliers like double, once, and twice;

3) postdeterminers (which follow central determiners). Postdeterminers

fall into two subgroups: a) ordinal numerals and the semi-determiners same,

other, former, latter, last, and next; b) cardinal numerals and quantifying

determiners.

3.

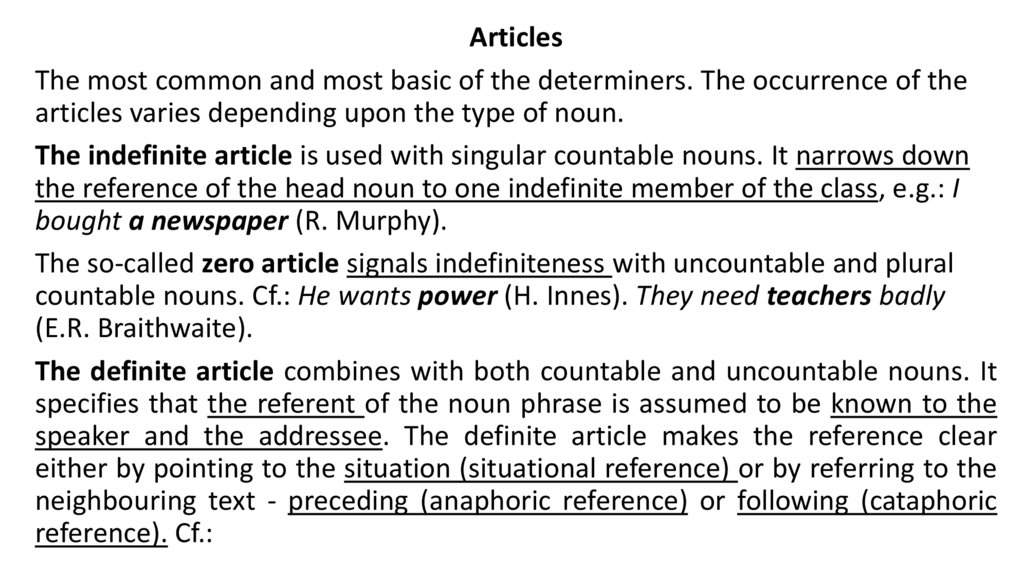

ArticlesThe most common and most basic of the determiners. The occurrence of the

articles varies depending upon the type of noun.

The indefinite article is used with singular countable nouns. It narrows down

the reference of the head noun to one indefinite member of the class, e.g.: I

bought a newspaper (R. Murphy).

The so-called zero article signals indefiniteness with uncountable and plural

countable nouns. Cf.: He wants power (H. Innes). They need teachers badly

(E.R. Braithwaite).

The definite article combines with both countable and uncountable nouns. It

specifies that the referent of the noun phrase is assumed to be known to the

speaker and the addressee. The definite article makes the reference clear

either by pointing to the situation (situational reference) or by referring to the

neighbouring text - preceding (anaphoric reference) or following (cataphoric

reference). Cf.:

4.

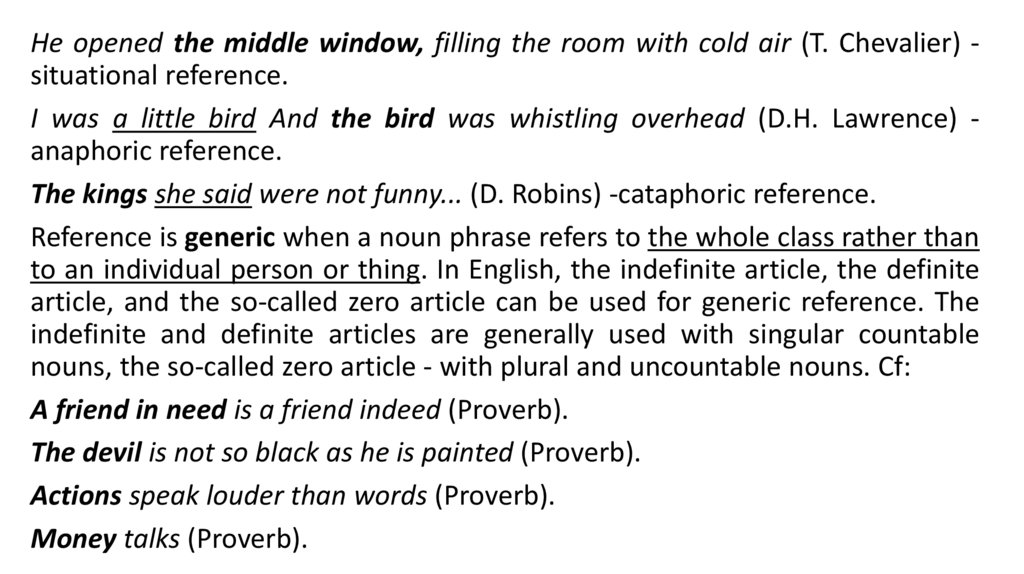

He opened the middle window, filling the room with cold air (T. Chevalier) situational reference.I was a little bird And the bird was whistling overhead (D.H. Lawrence) anaphoric reference.

The kings she said were not funny... (D. Robins) -cataphoric reference.

Reference is generic when a noun phrase refers to the whole class rather than

to an individual person or thing. In English, the indefinite article, the definite

article, and the so-called zero article can be used for generic reference. The

indefinite and definite articles are generally used with singular countable

nouns, the so-called zero article - with plural and uncountable nouns. Cf:

A friend in need is a friend indeed (Proverb).

The devil is not so black as he is painted (Proverb).

Actions speak louder than words (Proverb).

Money talks (Proverb).

5.

Is the Article a Word or a Morpheme?According to J. Vendryes and M.D. Fridman, the article is a grammatical morpheme

of the noun. The article, just like the morpheme, functions as an exponent of

grammatical meaning. In Bulgarian, Romanian and some other languages the suffix

form of the article also testifies to its morphemic nature.

In English, however, the article, unlike the morpheme, is autonomous:

• it never makes one word with the noun,

• it can be separated from the noun by an adjective, e.g.:

He is a clever workman (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson).

That's why A.I. Smirnitsky, T.V. Sokolova and other linguists think that the English

article is not a grammatical morpheme, but a separate word.

M.D. Fridman raises the following arguments against this point of view.

• The criterion of solid or hyphenated spelling is not a reliable one because it allows

of various fluctuations.

• It is not only words but also grammatical morphemes that can move about in the

sentence, e.g. the woman next door's husband (M. Swan), where the grammatical

morpheme - 's standing in logical connection with the noun woman is attached to

the noun door.

6.

Is the Article a Word or a Morpheme?The second argument of M.D. Fridman sounds rather convincing. But the number of

cases in which a grammatical morpheme is separated from the element it modifies is

very small, practically it is limited to the genitive case inflection - 's.

M.D. Fridman thinks that the only objective criterion of an element being a word and

not a morpheme is its ability to function in an absolute position. Since the article

lacks this ability, it should be qualified as a morpheme.

M.D. Fridman is right: articles are practically never used independently. But the

same is true of prepositions, conjunctions, etc. This syntactic 'defectiveness',

according to V.V. Vinogradov, is one of the main points of difference between the socalled notional (or lexical) and structural (or function) words.

Thus, M.D. Fridman's treatment of articles as grammatical morphemes does not

stand criticism. The article in English is not a grammatical morpheme, but a word.

This conception is shared by the majority of Russian and foreign linguists.

7.

Possessive DeterminersPossessive determiners specify a noun phrase by relating it to the

speaker/writer (my. our), the addressee (your) or other entities mentioned in

the text or given in the speech situation (his, her, its, their). Possessive

determiners correspond to personal pronouns (my - /, our - we, your - you,

his - he, her - she, its - it, their ~ they). Possessive determiners make noun

phrases definite. Cf:

My words at least had their effect (T. Chevalier).

Closely related to possessive determiners are specifying genitives consisting

of a noun phrase and a genitive suffix, e.g.:

This is Peter's umbrella (V. Evans).

8.

Demonstrative DeterminersThe demonstrative determiners this/these and that/those are similar to the definite

article in conveying definite meaning. However, in addition to marking an entity as

known, they specify the number of the referent (this, that - singular, these, those

-plural) and whether the referent is near (this, these) or distant in relation to the

speaker (that, those). In addition, the demonstrative determiners are stressed,

whereas the definite article is almost always unstressed.

Like the definite article, the demonstrative determiners can make the reference

clear either by pointing to the situation, or by referring to the preceding or

following text. Cf:

/ saw Mrs. Jones this morning (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

Shall we adopt these methods or those! (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

Who -was that man J saw you talking to? (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

Those sweets you gave me -were very nice (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

9.

.Quantifiers

These determiners specify nouns in terms of quantity. They combine with both indefinite

and definite noun phrases. In the latter case, they are generally followed by the preposition

of. Cf.: Most people take their holidays in the summer (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English). But most of the day was spent upstairs (C. McCullers).

Quantifiers can be broadly divided into four groups.

1. Inclusive: all, both, each, and every. All refers to the whole of a group or a mass; it

combines with both countable and uncountable nouns. Both is used with reference to two

entities with plural countable nouns. Cf.: All children hate exams (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English). Don't go to that awful man and spend all that money (D. Biber et

al.). Both her parents are doctors (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

Each and every refer to the individual members of a group and combine only with singular

countable nouns. Each stresses the separate individual; every stresses the individual as a

member of the group. Cf: We want every child to succeed (M. Swan).

Each child will find his own personal road to success (M. Swan).

10.

2. Large quantity.Many and much specify a large quantity: many - with plural countable nouns, much - with

uncountable nouns. They are typically used in interrogative and negative contexts. Cf.: Do

you know many people? (R. Murphy). They didn 't ask me many questions (R. Murphy).

Do you drink much coffee? (R. Murphy). There isn 't much milk in the fridge (R.

Murphy).

Other determiners specifying a large quantity are a great/good many (with plural countable

nouns), a great/good deal (with uncountable nouns), plenty of, a lot of, and lots of. Cf:

There are a great many reasons why you shouldn 't do it (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English). We received a good many offers of support (Longman Dictionary

of Contemporary English). A great deal of money has been spent on the new hospital

(Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English). He has had to spend a good deal of

money on medicines (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson). There are plenty of eggs in

the house (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson). A lot of people speak English (R.

Murphy). We 've played lots of matches this season (M. Swan).

11.

3.Moderate or small quantity.

Some usually specifies a moderate quantity and is used with both uncountable

and plural countable nouns, Cf.:

I've just made some coffee (R. Murphy).

There are some beautiful flowers in the garden (R. Murphy).

Determiners specifying a small quantity are a few, few, and several with plural

countable nouns, and a little and little with uncountable nouns. A few and a

little are close in meaning to some; few and little suggest that the quantity is

less than expected. Cf:

Last night I wrote a few letters (R. Murphy).

I've read it several times (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A,C. Gimson).

He is not well known. Few people have heard of him (R. Murphy).

She didn't eat anything, but she drank a little water (R. Murphy).

In summer the weather is very dry. There is little rain (R. Murphy).

12.

4.Arbitrary/negative member or amount.

Any denotes an arbitrary member of a group, or an arbitrary amount of a mass. It

combines with both countable and uncountable nouns. Either has a similar meaning,

but it is used with groups of two and combines only with singular countable nouns.

Both any and either are typically used in negative and interrogative contexts. Cf.:

They didn 'I make any mistakes (R. Murphy).

Are there any letters for me this morning*? (R. Murphy).

I haven't got any money (R. Murphy).

Have you got any money'? (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

She's lived in London and Manchester, but doesn 't like either city very much

(Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

No and neither have negative reference, the former -generally, the latter - with

reference to two entities. Cf.:

I have no socks (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

Neither road is very good (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

13.

NumeralsCardinal numerals are related to quantifiers, but differ from them in

providing a numerical rather than a more general specification.

Ordinal numerals specify nouns in terms of order. They are similar to the socalled semi-determiners.

Cf.: Brazil beat France by two goals to one (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English).

That's the second time you've asked me that (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English).

When the two types of numerals occur together in one noun phrase, ordinal

numerals normally precede cardinal numerals, e.g.:

In the first two minutes of the match, the Garden School boys came very close

to the City School's goal... (L.A. Hill).

14.

Semi-determinersIn addition to determiners proper, there are some determiner-like words which are

often described as adjectives. However, they differ from adjectives in that they have

no descriptive meaning and primarily serve to specify the reference of the noun.

Moreover, they are characterized by special co-occurrence patterns with other

determiners. Most semi-determiners co-occur only with the definite article. There are

four major pairings of semi-determiners: same and other, former and latter; last and

next; certain and such.

1. Same and other.

Same may be added after the definite article to emphasize that the reference is

exactly to the person or thing mentioned before,

e.g.- That's the same man that asked me for money yesterday (M. Swan).

Other is the opposite of same and specifies that the reference is to something or

somebody different from the person or thing mentioned previously. It may be added

after the definite article, the indefinite article (taking the form another), and

possessive determiners, or it may occur as the only determiner in indefinite noun

phrases. e.g.- She is cleverer than the other girls in her class (Longman Dictionary

of Contemporary English).

Will you have another cup of tea? (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson).

15.

2.Former and latter.Former and latter may be added after the definite article to discriminate between the

first and the second of two things or people already mentioned. Cf.: Of Nigeria and

Ghana, the former country has the larger population (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English). If offered red or white, I'd choose the latter wine (Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English). Former and latter can also be used with

reference to time.

3.

Last and next.

Last and next are like ordinal numerals in specifying items in terms of order. They

regularly combine with the definite article or some other definite determiner, except

when used in deictic time expressions, with present time as the situational point of

reference (such as last week, next Thursday, etc.). Cf.: George was the last person to

arrive (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English). When you 've finished this

chapter go on to the next one (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English). We

went there last Sunday and we're again going next Sunday (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English).

16.

4. Certain and such.Certain and such differ from the other semi-determiners in being used only in

indefinite noun phrases. Certain singles out a specific person/thing or some specific

people/things. Such refers to a person/thing or people/things of a particular kind. Cf.:

There are certain reasons why this information cannot be made public (Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English).

Such people as him shouldn't be allowed here (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

Wh-determiners

Wh-determiners are used as interrogative clause markers and relativizers (i.e. words

that introduce relative clauses).

Cf: Whose house is this? (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

Which shoes shall I wear, the red ones or the brown ones? (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English).

That's the man whose house was burned down (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

I told him to go to a doctor, which aavice he took (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C.

Gimson).

17.

PronounsD. Biber and his co-authors refer to function words those pronouns that are

used absolutely, without a head noun. They regard them as function words

because they do not give a detailed specification, but serve as pointers

requiring the listener or reader to find the exact meaning in the surrounding

text or in the speech situation, e.g.:

I saw the accident (The New Webster's Grammar Guide) -personal pronoun.

Jane saw me at the game (The New Webster's Grammar Guide) - personal

pronoun.

Who told you this? (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English) demonstrative pronoun.

She hurt herself (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English) - reflexive

pronoun.

18.

They told each other about their families (Longman Dictionary of ContemporaryEnglish) - reciprocal pronoun equivalent.

But this dog isn't mine! It's his (V. Evans) – possessive pronouns.

Somebody took my coat (The New Webster's Grammar Guide) - indefinite pronoun.

Which is your car? (The New Webster's Grammar Guide) -interrogative pronoun.

This is the dog which was lost (The New Webster's Grammar Guide) - relative

pronoun.

In addition to pronouns, there are some other function words which recapitulate a

neighbouring expression, with the effect of reducing grammatical complexity. The

following are the most important.

1.

The pro-form so, which replaces clauses or verb complements, e.g.:

Do you think it will rain? - Yes, I think so (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson).

2.

The pro-predicates do and do so. Cf.: She likes jazz, and I do as well (M. Swan).

Put the car away, please, - I've already done so (M. Swan).

19.

In addition to pronouns, there are some other function words which recapitulate aneighbouring expression, with the effect of reducing grammatical complexity. The

following are the most important.

1.

The pro-form so, which replaces clauses or verb complements, e.g.:

Do you think it will rain? - Yes, I think so (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson).

2. The pro-predicates do and do so. Cf.: She likes jazz, and I do as well (M.

Swan). Put the car away, please, - I've already done so (M. Swan).

Auxiliaries

D. Biber and his co-authors draw a distinction between auxiliaries proper (or

primary auxiliaries) and modal auxiliaries. The primary auxiliaries specify the

morphological categories of the lexical verb. The modal auxiliaries are largely

concerned with expressing 'modality', i.e. such concepts as ability, permission,

necessity, obligation, etc. Cf.:

He has just painted the room (V. Evans) - primary auxiliary, perfect phase.

You must follow (he school rules (V. Evans) - modal auxiliary, obligation.

20.

PrepositionsTradition says that prepositions are function words that indicate relations between

nouns or noun equivalents and some other words in the sentence, e.g.: to think of

somebody (the preposition of indicates the relations between the pronoun

somebody and the verb to think);

Many prepositions in English correspond to case inflections in other languages.

According to B.A. liyish, prepositions express relations between objects of extra

linguistic reality. For instance, in the sentence The ball is in the box (V. Evans),

the preposition in indicates relations in space between two things: the ball and the

box.

The latter seems highly debatable. Being a linguistic notion, the preposition

cannot serve the purpose of expressing relations between objects of extra

linguistic reality.

The accident occurred under/ near/ above/behind/beneath the bridge (The New

Webster's Grammar Guide).

21.

R. Quirk and his co-authors think the meanings of space and time to be mosttypical of prepositions, although they mention also such meanings rendered

by prepositions as cause, goal, origin, and some others.

D. Biber and his co-authors draw a distinction between free and bound

prepositions.

• Free prepositions have an independent meaning; the choice of a free

preposition is not dependent upon any specific words in the context.

• In contrast, bound prepositions often have little independent meaning, and

the choice of a preposition depends upon some other word (often the

preceding verb). The same prepositional form can function as a free or a

bound preposition.

Cf.: There is a picture on the wall (V. Evans) - free preposition.

Good health depends upon/on good food, exercise and getting enough sleep

(A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson) - bound preposition.

22.

Although some prepositions can be both free and bound, many prepositions arealways, or almost always, free: above, across, against, along, among(st), before,

behind, beside, between, beyond, during, inside, near, opposite, outside, past,

since, till, toward(s), under, until, etc.

In addition, phrasal prepositions are normally free. As far as their makeup is

concerned, prepositions fall into the following groups:

simple, e.g.: in, on, at, for, with, etc.,

derivative, e.g.: behind, below, across, etc.,

compound, e.g.: inside, outside, within, etc.

Some linguists speak of the so-called phrasal prepositions. Here belong the

groups out of, because of, in front of, etc. Just like prepositions proper, they

always stand before the word they govern, are introduced into speech readymade, and have the same meaning of showing relations between a noun or a

noun equivalent and some other word. Cf.:

A woman is getting out of her car (V. Evans).

Agnes was sitting on the bench in front of our house (T. Chevalier).

23.

Adverbial ParticlesAdverbial particles are a small group of short invariable forms with a core

meaning of motion and result. The most important are: about, across, along,

around, aside, away, back, by, down, forth, in, off, out, over, past, round, through,

under, etc.

While prepositions have a special relationship to nouns, adverbial particles are

closely linked to verbs. As opposed to prepositions that usually precede nouns,

adverbial particles generally follow verbs.

Adverbial particles are used in two main ways: 1) to build phrasal verbs, 2) to build

extended prepositional phrases. Cf.:

My aunt brought up four children (R. Courtney).

We were going back to the hotel when it happened (D. Biber etal.).

Conjunctions

A conjunction is a function word which joins syntactic units: words, parts of clauses,

clauses, sentences, etc. Traditionally, conjunctions are subdivided into coordinating

and subordinating.

Coordinating conjunctions (or coordinators) link elements of equal rank. Cf.:

He fell and broke my arm (The New Webster's Grammar Guide).

24.

Subordinating conjunctions (or subordinators) serve to introduce a dependentclause, e.g.:

We came here because it was cheap (J. Updike).

Coordinators are usually classified into additive (and), adversative (but), and

disjunctive (or).

Subordinators fall into three major subclasses.

1) The great majority of subordinators introduce adverbial clauses: after, as,

because, since, (al)though, while, etc.

2) Three subordinators introduce degree clauses: as, than, and that, e.g.:

Profits are higher than they were last year (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

3) Three subordinators introduce complement clauses: if, that, and whether e.g.:

It was uncertain whether she would recover (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English).

25.

As far as their makeup is concerned, conjunctions fall into the followinggroups:

1) simple, e.g.: and, but, so, though, etc.;

2) compound, e.g.: however, nevertheless, notwithstanding, etc.;

3) phrasal, e.g.: as soon as, on condition that, in order that, as if, as though, in

case, etc.;

4) Correlative conjunctions usually consist of two parts which always go

together, e.g.: both ... and, either ... or, neither ... nor, as ... as, etc.

Cf.: We visited both New York and London (Longman Dictionary of

Contemporary English).

Either the dog or the cat has eaten it (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie, A.C. Gimson).

He drove as fast as he could (M. Swan).

26.

Prepositions, in the opinion of M. Bryant, have much in common withconjunctions.

• First, many prepositions are homonymous with conjunctions, e.g.: after, since.

• Second, sometimes prepositions and conjunctions indicate similar relations. Cf.: I

with my friend and my friend and I. As regards their form, both are invariable.

Their meaning is abstract and vague.

The preposition differs from the conjunction in having a more uniform right-hand

distribution (generally a noun). However, even functionally prepositions are

acquiring more and more features in common with conjunctions. Just like

conjunctions, prepositions now often occur at the head of a clause, e.g.:

There is much in what you say (J.B. Opdycke).

Since prepositions and conjunctions are close semantically, morphologically and

even syntactically, it is, perhaps, possible to unite them into one group of

connectives.

27.

Wh-wordsWh-words are used in two ways: as interrogative clause markers and as

relativizers. Cf.:

What will happen to her nowl (H. Fielding).

Mr. Miller, who lived next door, moved to Canada (The New Webster's

Grammar Guide).

Existential 'there'

It is often described as an anticipator)' subject. No other word behaves in the

same way, heading a clause, expressing existence, e.g.:

There is a blackboard in the classroom (V. Evans).

The Negator 'Not'

The main use of not is to make a whole clause negative, e.g.: I did not make

up an answer fast enough (T. Chevalier). Apart from negating whole clauses,

not has various other negative uses, e.g.: not all, not many, etc.

28.

The Infinitive Marker 'To'As a rule, the infinitive is used with the marker to, e.g. I was glad to leave

(T. Chevalier).

Numerals

D. Biber and his co-authors refer those cardinal and ordinal numerals to

function words that occur as heads of noun phrases. Cf.: Four of the yen

traders have pleaded guilty (D. Biber et al.).

Three men will appear before Belfast magistrates today on charges of

intimidation. A fourth will be charged with having information likely to be

of use to terrorists (D. Biber et al.).

When cardinal and ordinal numerals are used as heads of noun phrases,

they are substantivized and can be regarded as nouns, not numerals.