Similar presentations:

Parts of speech

1.

Parts of speechPresented by Zhanna M. Sagitova

2.

Problems to be discussed:- brief history of grouping words to parts of speech

- contemporary criteria for classifying words to parts of speech

- structural approach to the classification of words (the doctrine of

American descriptive School)

- notional and functional parts of speech

- A comprehensive approach to the discrimination of parts of speech

3.

In every language we find groups of words that share grammaticalcharacteristics that are called “parts of speech”.

4.

Parts of speech are grammatical (or lexico-grammatical) classes ofwords identified on the basis of the three criteria:

- the meaning common to all the words of the given class;

- the form with the morphological characteristics of a type of word;

- the function in the sentence typical of all the words of this class

(e. g. the English noun has the categorical meaning of “thingness”, the

changeable forms of number and case, and the functions of the

subject, object and substantive predicative).

5.

The notion of “parts of speech” goes back to the times of AncientGreece. Aristotle (384–322 B. C.) distinguished between nouns, verbs

and connectives. Traditional grammars of English, following the

approach which can be traced back to Latin, agreed that there were

eight parts of speech in English: the noun, pronoun, adjective, verb,

adverb, preposition, conjunction and interjection.

6.

The main problem with the traditional classification is that somegrammatical phenomena given above have intermediary features in

this system.

They make up a continuum, a transition zone, between the polar

entities.

For example, there is a very specific group of quantifiers in English

(such words as many, much, little, few). They have features of

pronouns, numerals, and adjectives and are referred to as “hybrids”.

7.

Many language experts mention "the eight parts of speech" whendiscussing language (such as Weaver in 1996). However, the number of

parts of speech we must acknowledge in a language is determined by

the level of detail in our analysis. The more detailed the analysis, the

more parts of speech we will distinguish.

8.

We distinguish nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs (the major partsof speech), and pronouns, wh-words, articles, auxiliary verbs,

prepositions, intensifiers, conjunctions, and particles (the minor parts

of speech).

9.

Every literate person needs at least a minimal understanding of parts ofspeech in order to be able to use such commonplace items as

dictionaries and thesauruses, which classify words according to their

parts (and sub-parts) of speech.

10.

For example, the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, p. xxxi)distinguishes adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, definite articles,

indefinite articles, interjections, nouns, prepositions, pronouns, and

verbs. It also distinguishes transitive, intransitive, and auxiliary verbs.

11.

Writers and writing teachers need to know about parts of speech inorder to be able to use and teach about style manuals and school

grammars. Regardless of their discipline, teachers need this

information to be able to help students expand the contexts in which

they can effectively communicate.

12.

The parts of speech that contribute the most to a message are calledcontent words, while other parts of speech are known as function or

structure words.

The content words are the ones that we see in newspaper headlines

where space is at a premium and they are the words we tend to keep in

text messaging where costs per word can be high. However, in most

types of discourse, function words significantly outnumber content

words.

13.

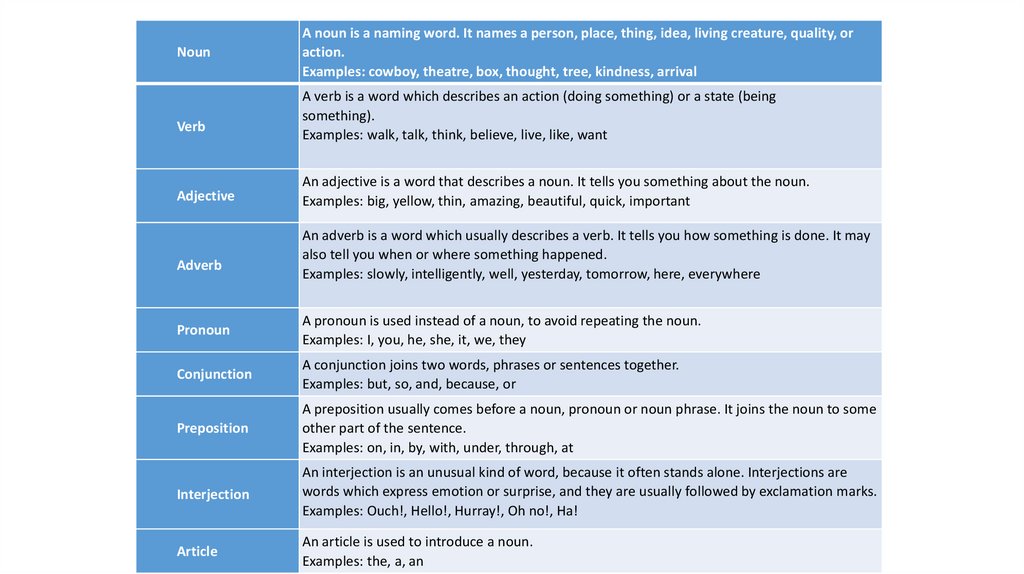

NounVerb

Adjective

Adverb

A noun is a naming word. It names a person, place, thing, idea, living creature, quality, or

action.

Examples: cowboy, theatre, box, thought, tree, kindness, arrival

A verb is a word which describes an action (doing something) or a state (being

something).

Examples: walk, talk, think, believe, live, like, want

An adjective is a word that describes a noun. It tells you something about the noun.

Examples: big, yellow, thin, amazing, beautiful, quick, important

An adverb is a word which usually describes a verb. It tells you how something is done. It may

also tell you when or where something happened.

Examples: slowly, intelligently, well, yesterday, tomorrow, here, everywhere

Pronoun

A pronoun is used instead of a noun, to avoid repeating the noun.

Examples: I, you, he, she, it, we, they

Conjunction

A conjunction joins two words, phrases or sentences together.

Examples: but, so, and, because, or

Preposition

A preposition usually comes before a noun, pronoun or noun phrase. It joins the noun to some

other part of the sentence.

Examples: on, in, by, with, under, through, at

Interjection

An interjection is an unusual kind of word, because it often stands alone. Interjections are

words which express emotion or surprise, and they are usually followed by exclamation marks.

Examples: Ouch!, Hello!, Hurray!, Oh no!, Ha!

Article

An article is used to introduce a noun.

Examples: the, a, an

14.

Most parts of speech can be divided into sub-classes in accordance withvarious particular semantico-functional and formal features of the

constituent words. This subdivision is sometimes called "subcategorisation"

of parts of speech.

nouns are subcategorised into proper and common, countable and

uncountable, concrete and abstract, etc. e.g.: Mary, Robinson, London, the

Mississippi, Lake Erie - girl, person, city, river, lake; man, scholar, leopard,

butterfly - earth, field, rose, machine; coin/coins, floor/floors, kind/kinds news, growth, water, furniture; stone, grain, mist, leaf - honesty, love,

slavery, darkness.

Prepositions can be divided into prepositions of time, prepositions of place

etc. Nouns can be divided into proper nouns, common nouns, concrete

nouns etc.

15.

Some scholars consider words as falling into two broad categories:closed class words and open class words.

The former consists of words that are relatively stable and unchanging

in the language.

Closed classes of words are:

pronoun /she, they/,

determiner /the, a/,

primary verb /be/,

modal verb /can, might/,

preposition /in, of/,

conjunction /and, or/

and auxiliaries /do, does/.

16.

These words play a major part in English grammar, often correspondingto inflections in some other languages, and they are sometimes

referred to as ‘grammatical words’, ‘function words’, or ‘structure

words’. They have a grammatical function as structural markers: a

determiner defines the beginning of a noun phrase, a preposition – the

beginning of a prepositional phrase, a conjunction – the beginning of a

clause.

17.

Contemporary criteria for classifying words into parts ofspeech

The problem of word classification into parts of speech still remains

one of the most controversial problems in modern linguistics. The

attitude of grammarians with regard to parts of speech and the basis of

their classification varied a good deal at different times. Only in English

grammarians have been vacillating between 3 and 13 parts of speech.

There are four approaches to the problem:

• Classical (logical-inflectional)

• Functional

• Distributional

• Complex

18.

The classical parts of speech theory goes back to ancient times. It isbased on Latin grammar. According to the Latin classification of the

parts of speech all words were divided dichotomically into declinable

and indeclinable parts of speech.

This system was reproduced in the earliest English grammars. The first

of these groups, declinable words, included nouns, pronouns, verbs

and participles,

the second – indeclinable words – adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions

and interjections.

The logicalinflectional classification is quite successful for Latin or other

languages with developed morphology and synthetic paradigms but it

cannot be applied to the English language because the principle of

declinability/indeclinability is not relevant for analytical languages.

19.

A new approach to the problem was introduced in the XIX century byHenry Sweet.

This approach may be defined as functional. He resorted to the

functional features of words and singled out nominative units and

particles.

To nominative parts of speech belonged noun-words (noun,

nounpronoun, noun-numeral, infinitive, gerund), adjective-words

(adjective, adjective-pronoun, adjective-numeral, participles), verb

(finite verb, verbals – gerund, infinitive, participles),

while adverb, preposition, conjunction and interjection belonged to the

group of particles. However, though the criterion for classification was

functional, Henry Sweet failed to break the tradition and classified

words into those having morphological forms and lacking

morphological forms, in other words, declinable and indeclinable.

20.

A distributional approach to the parts of speech classification can beillustrated by the classification introduced by Charles Fries. He wanted

to avoid the traditional terminology and establish a classification of

words based on distributive analysis, that is, the ability of words to

combine with other words of different types. Within this approach, the

part of speech is a functioning pattern and a word belonging to the

same class should be the same only in one aspect – occupy the same

position and perform the same syntactic function in speech utterances.

Charles Fries introduced this classification. He used the method of

frames (подстановки).

21.

e.g.:Frame A: The concert was good.

Frame B: The clerk remembered the tax.

Frame C: The team went there.

Words that can substitute the word “concert”, “clerk”, “team”, “the tax”

are Class 1 words.

Class 2 words are “was”, “remembered” and “went”.

Words that can take the position of “good” are Class 3 words.

Words that can fill the position of “there” are called Class 4 words.

22.

It turned out that his four classes of words were practically the same astraditional nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

What is really valuable in Charles Fries‘ classification is his investigation

of 15 groups of function words (form-classes) because he was the first

linguist to pay attention to some of their peculiarities.

23.

The drawback of this classification is that morphological and semanticproperties are completely neglected, because words of different nature

are treated as items of the same class and vice a versa.

24.

R. Khaimovich and Rogovskaya identify five criteria1. Lexico - grammatical meaning of words

2. Lexico - grammatical morphemes (stem - building elements)

3. Grammatical categories of words.

4. Their combinability (unilateral, bilateral)

5. Their function in a sentence.

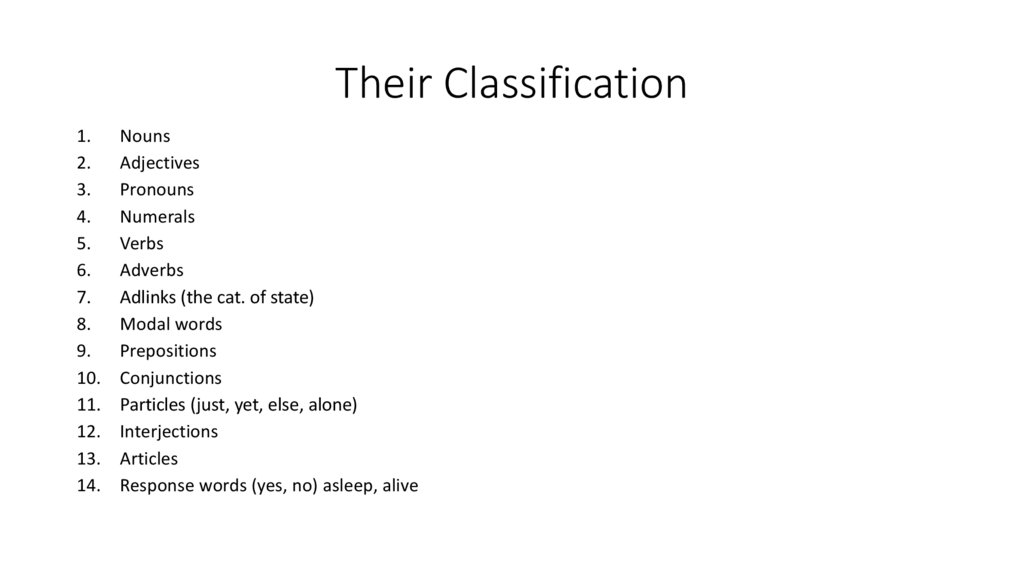

25.

Their Classification1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

Nouns

Adjectives

Pronouns

Numerals

Verbs

Adverbs

Adlinks (the cat. of state)

Modal words

Prepositions

Conjunctions

Particles (just, yet, else, alone)

Interjections

Articles

Response words (yes, no) asleep, alive

26.

As authors state the parts of speech lack some of those five criteria.The most general properties of parts of speech are features 1, 4 and 5.

27.

B. A. Ilyish distinguishes three criteria:1. meaning;

2. Form;

3. function.

The third criteria is subdivided into two:

a) the method of combining the word with other ones (deal with

phrases)

b) the function in the sentence (deals with sentence structure).

28.

B. A. Ilyish considers the theory of parts of speech as essentially a part ofmorphology, involving, however, some syntactical points.

1. Nouns

2. Adjective

3. Pronoun

4. Numerals

5. Statives (asleep, afraid)

6. Verbs

7. Adverbs

8. Prepositions .

9. Conjunctions

10. Particles

11. Modal words

12. Interjections

29.

L. Barkhudarov & D. Steling’s classification of words arebased on four principles.

The important and characteristic feature of their classification is that they do not make use of syntactic

function of words in sentences: meaning, grammatical forms, combinability with other words and the types of

word - building (which are studied not by grammar, but by lexicology).

1.

Nouns

2.

Articles

3.

Pronouns

4.

Adjectives

5.

Adverbs

6.

Numerals

7.

Verbs

8.

Prepositions

9.

Conjunctions

10.

Particles

11.

Modal words

12.

Interjections

30.

In modern linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated on the basis ofthe three criteria: “semantic”, “formal”, and “functional”.

31.

The semantic criterion presupposes the evaluation of the generalizedmeaning, which is characteristic of all the subset of words constituting

a given part of speech. This meaning is understood as the “categorial

meaning of the part of speech”.

32.

The formal criterion provides for the exposition of the specificinflexional and derivational (word-building) features of all the lexemic

subsets of a part of speech.

33.

The functional criterion concerns the syntactic role of words in thesentence typical of a part of speech. The said three factors of categorial

characterization of words are conventionally referred to as,

respectively, “meaning”, “form”, and “function”.

34.

A comprehensive approach to thediscrimination of parts of speech

The complex approach to the problem of parts of speech classification

was introduced by academician L. V. Shcherba, who proposed to

discriminate parts of speech on the basis of three criteria: semantic,

formal and functional.

35.

By the semantic criterion he understood the generalized meaning orgeneral grammatical meaning, which is characteristic of all the words,

constituting a given part of speech, i.e. categorial meaning of parts of

speech (e.g. the general grammatical meaning of nouns is substance;

verbs – verbiality, i.e. the ability to express actions, processes or states;

adverbs – adverbiality, i.e. the ability to express qualities or properties

of actions, processes or states; adjectives – qualitiativeness, i.e. the

ability to express qualities or properties of substances).

36.

Taken separately, the semantic criterion cannot be sufficient for wordclass discrimination, as there are lexemes of a part of speech, which

acquire the general meaning of the other part of speech (e.g. action – a

noun, which expresses verbiality, sleep – a noun, which expresses

process, blackness – a noun, which expresses quality). Thus, the

general grammatical categorial meaning is important for part of speech

classification, it is the intrinsic quality of a part of speech, it

predetermines some outward properties of its lexemes but it cannot

play the role of an absolute criterion of word classification.

37.

The formal criterion provides for the exposition of the specificinflexional and derivational (word-building) features of words of a part

of speech and deals with the morphological properties of words, which

include:

1) the system of inflexional morphemes of words, typical of a certain

part of speech;

2) the system of derivational lexico-grammatical morphemes,

characteristic of a part of speech.

38.

Closed-System Items(a) noun - John, room, answer, play adjective - happy, steady, new,

large, round adverb -steadily, completely, really, very, then verb search, grow, play, be, have, do

(b) article ~the,a(n) demonstrative - that, this pronoun - he, they,

anybody, one, which preposition - of, at, in, without, in spite of

conjunction - and, that, when, although interjection - oh, ahugh, phew

39.

The parts of speech are listed in two groups, (a) and (b), and thisintroduces a distinction of very great significance.

Set (b) comprises what are called "closed-system" items. That is, the

sets of items are closed in the sense that they cannot normally be

extended by the creation of additional members: a moment's reflection

is enough for us to realize how rarely in a language we invent or adopt

a new or additional pronoun.

It requires no great effort to list all the members in a closed system,

and to be reasonably sure that one has in fact made an exhaustive

inventory (especially, of course, where the membership is so extremely

small as in the case of the article).

40.

The items are said to constitute a system in being (1) reciprocallyexclusive: the decision to use one item in a given structure excludes the

possibility of using any other (thus one can have "the book" or "a book"

but not "*a the book");

and (2) reciprocally defining: it is less easy to state the meaning of any

individual item than to define it in relation to the rest of the system.

This may be clearer with a non-linguistic analogy. If we are told that a

student came third in an examination, the "meaning" that we attach to

"third" will depend on knowing how many candidates took the

examination: "third" in a set of four has a very different meaning from

"third" in a set of thirty.

41.

Open-Class ItemsBy contrast, set (a) comprises "open classes". Items belong to a class in that

they have the same grammatical properties and structural possibilities as

other members of the class (that is, as other nouns or verbs or adjectives or

adverbs respectively), but the class is "open" in the sense that it is

indefinitely extendable. New items are constantly being created and no one

could make an inventory of all the nouns in English (for example) and be

confident that it was complete. This inevitably affects the way in which we

attempt to define any item in an open class: while it would obviously be

valuable to relate the meaning of "room" to other nouns with which it has

semantic affinity (chamber, hall, house,...) one could not define it as "not

house, not box, not plate, not indignation,..." as one might define a closedsystem item like "this" as "not that".

42.

The distinction between "open" and "closed" parts of speech must betreated cautiously however. On the one hand, we must not exaggerate

the ease with which we create new words: we certainly do not make up

new nouns as a necessary part of speaking in the way that making up

new sentences is necessary. On the other hand, we must not

exaggerate the extent to which parts of speech in set (b) are "closed":

new prepositions (usually of the form "prep + noun + prep" like by way

of) are by no means impossible.

43.

Although they have deceptively specific labels, the parts of speech tendin fact to be rather heterogeneous. The adverb and the verb are

perhaps especially mixed classes, each having small and fairly welldefined groups of closed-system items alongside the indefinitely large

open-class items. So far as the verb is concerned, the closed-system

subgroup is known by the well-established term "auxiliary". With the

adverb, one may draw the distinction broadly between those in -ly that

correspond to adjectives (complete + -ly) and those that do 0ot (now,

there, forward, very, for example).

44.

Discussion on the article "Parts of speech: empirical and theoreticaladvances" by Umberto Ansaldo, Jan Don and Roland Pfau

45.

1. What are the main arguments or hypotheses proposed in the articleregarding parts of speech?

2. How do the authors define and categorize different parts of speech

in the context of their research?

3. What empirical data or examples do the authors use to support

their claims about parts of speech?

4. What are the key theoretical advances discussed in the article? How

do these advances contribute to our understanding of parts of

speech?

46.

5. What research methods or approaches do the authors use toanalyze parts of speech? Are these methods predominantly qualitative,

quantitative, or a mix of both?

6. How do the authors define and categorize different parts of speech in

the context of their research?

7. Are there any limitations or biases in the methodology that the

authors acknowledge? How might these affect the findings?

47.

8. How do the findings of this article impact the current understandingof parts of speech in linguistic theory?

9. What future research directions do the authors suggest? Are there

any specific areas they identify as needing further investigation?

10. How might the theoretical and empirical advances discussed in the

article influence practical applications, such as language teaching or

computational linguistics?

48.

11. Do you agree with the authors' conclusions and theoreticaladvancements? Why or why not?

12. How does the article compare with other recent work in the field?

Are there any significant differences or similarities in approach or

conclusions?

13. What are some potential real-world examples that could further

illustrate or challenge the points made in the article?

english

english