Similar presentations:

2 - Carracci

1. Annibale Carracci and Caravaggio

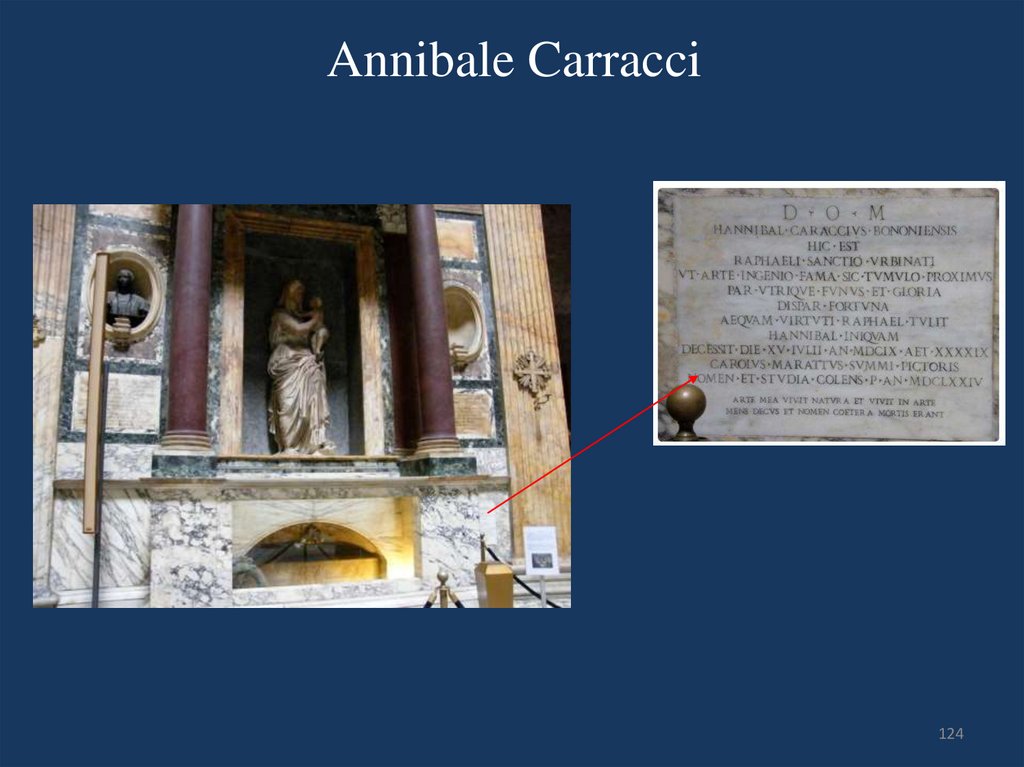

12. Annibale Carracci as the new Raphael

23. Caravaggio as the new Michelangelo

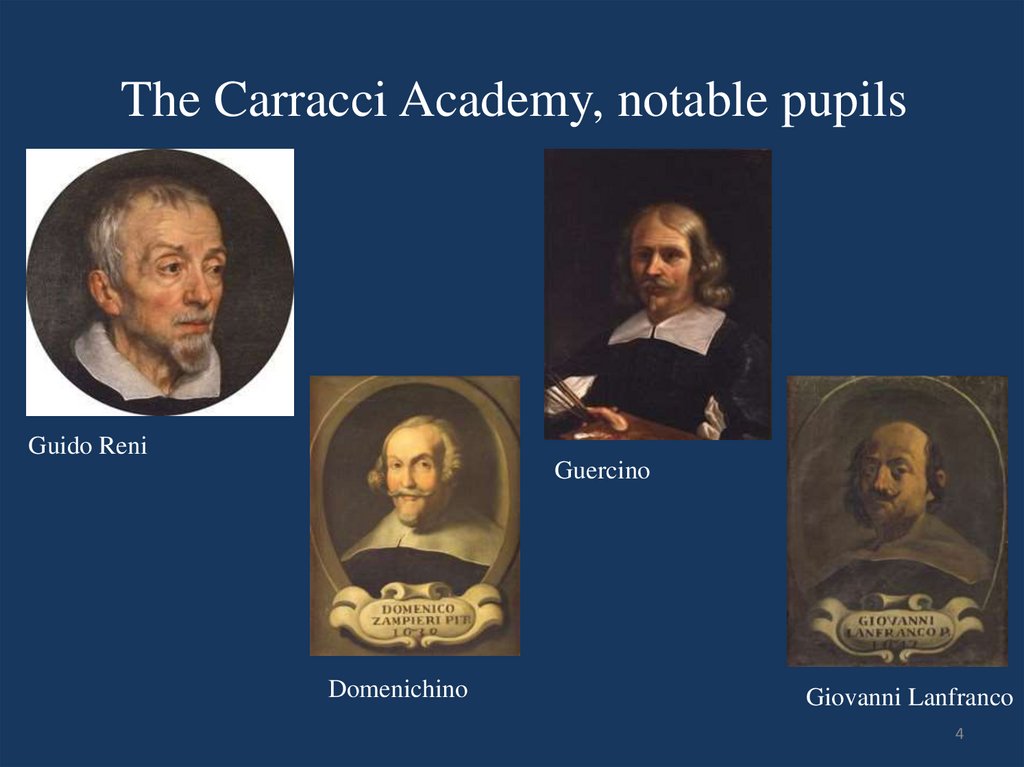

34. The Carracci Academy, notable pupils

Guido ReniGuercino

Domenichino

Giovanni Lanfranco

4

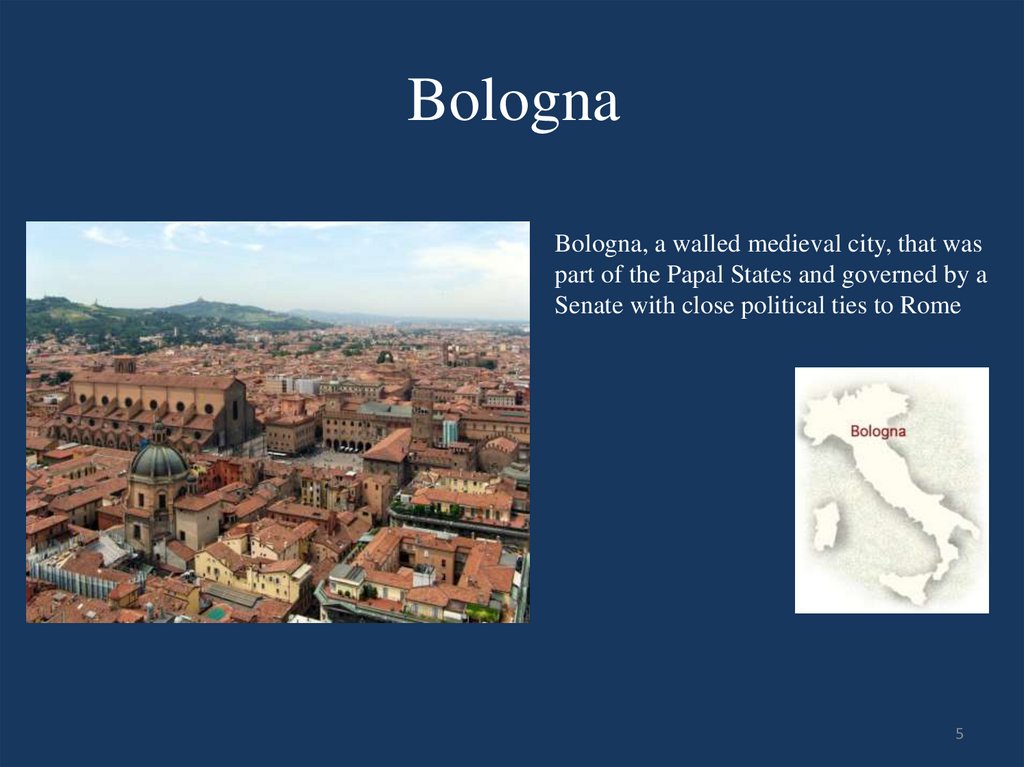

5. Bologna

Bologna, a walled medieval city, that waspart of the Papal States and governed by a

Senate with close political ties to Rome

5

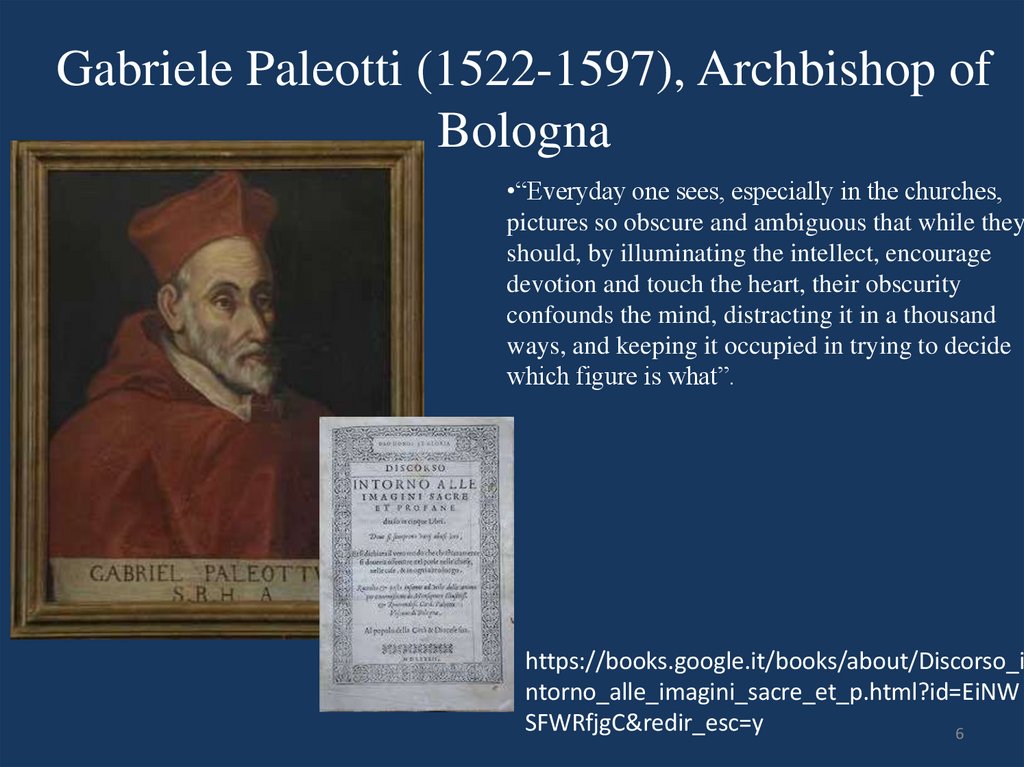

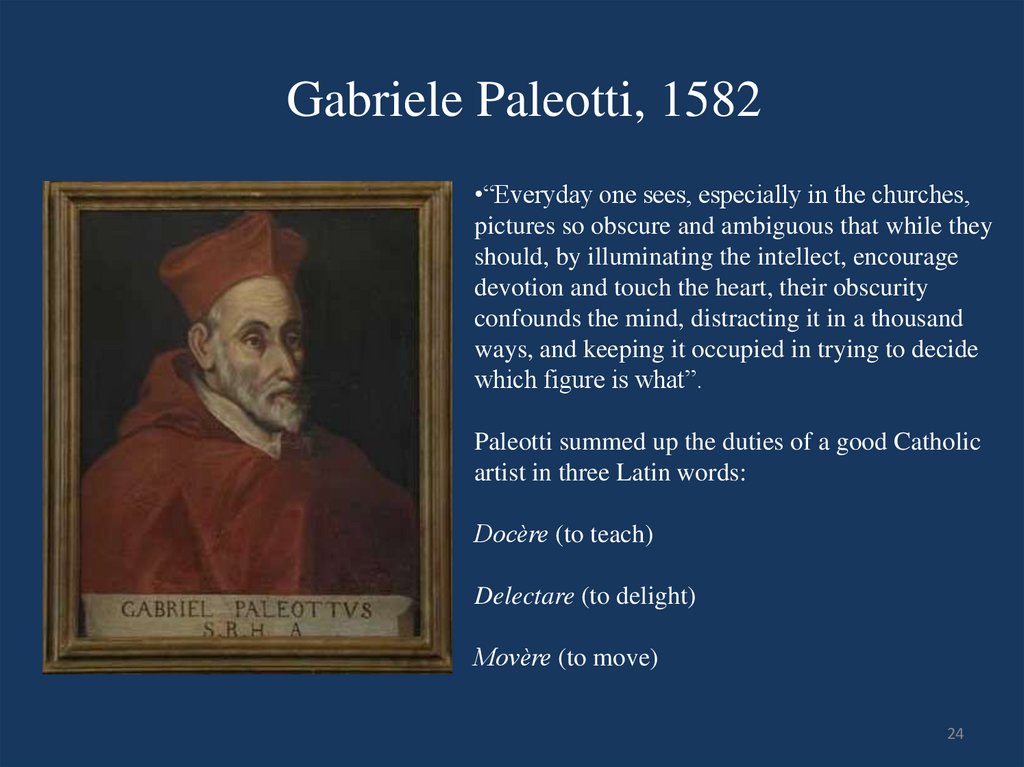

6. Gabriele Paleotti (1522-1597), Archbishop of Bologna

•“Everyday one sees, especially in the churches,pictures so obscure and ambiguous that while they

should, by illuminating the intellect, encourage

devotion and touch the heart, their obscurity

confounds the mind, distracting it in a thousand

ways, and keeping it occupied in trying to decide

which figure is what”.

https://books.google.it/books/about/Discorso_i

ntorno_alle_imagini_sacre_et_p.html?id=EiNW

SFWRfjgC&redir_esc=y

6

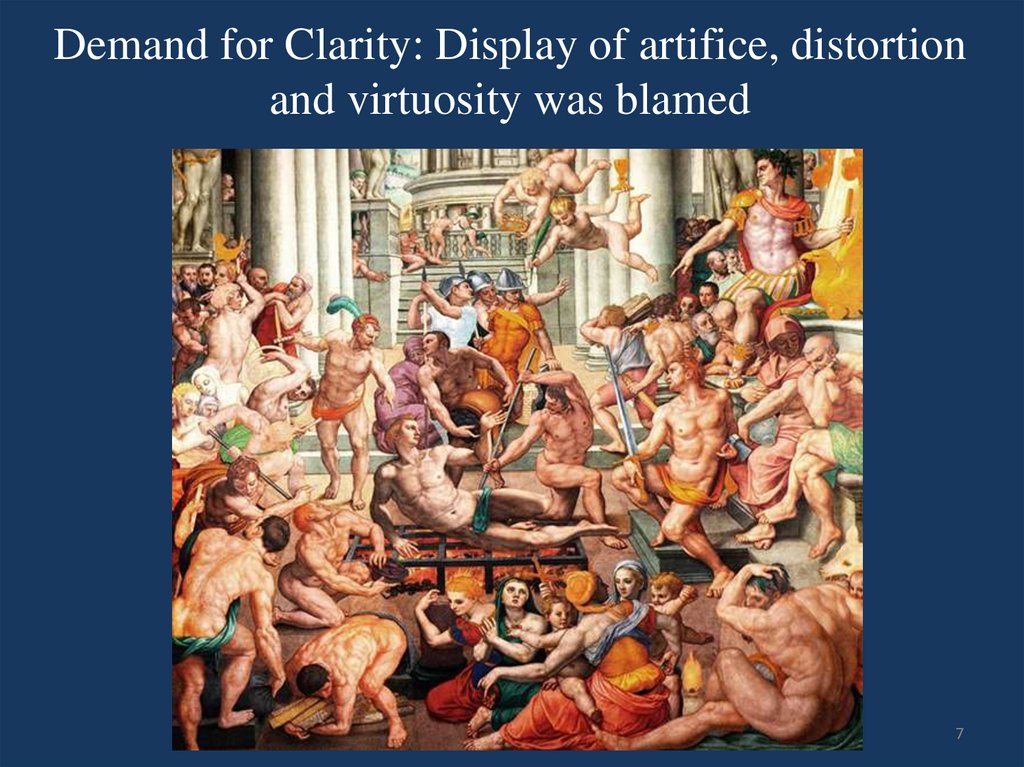

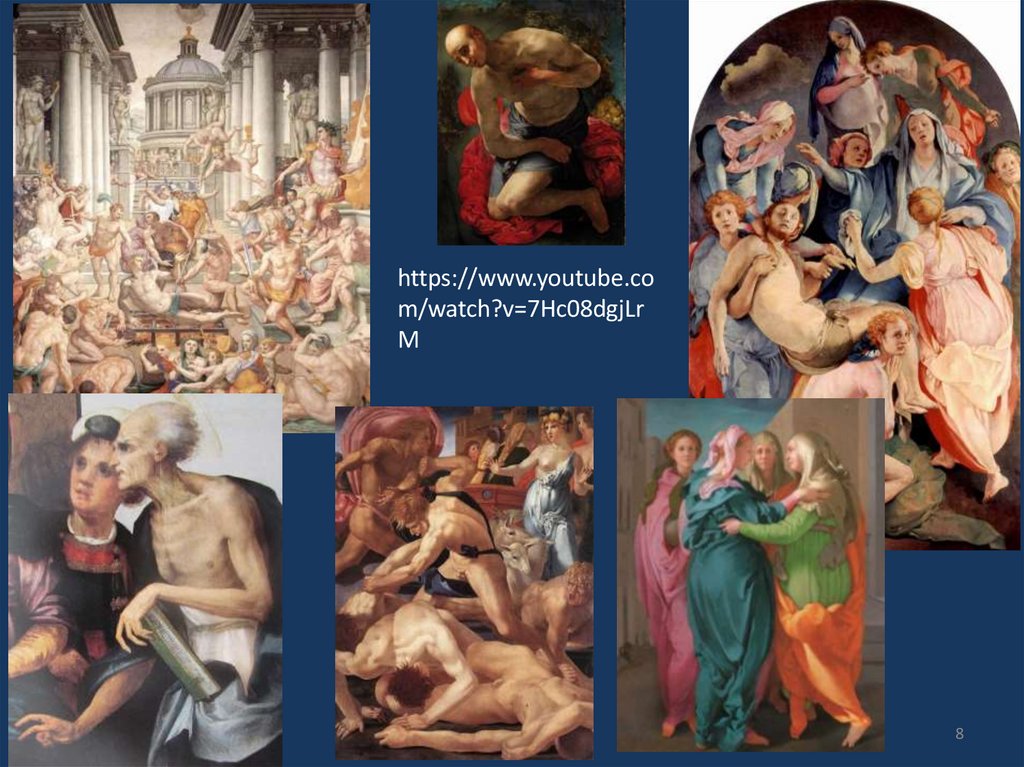

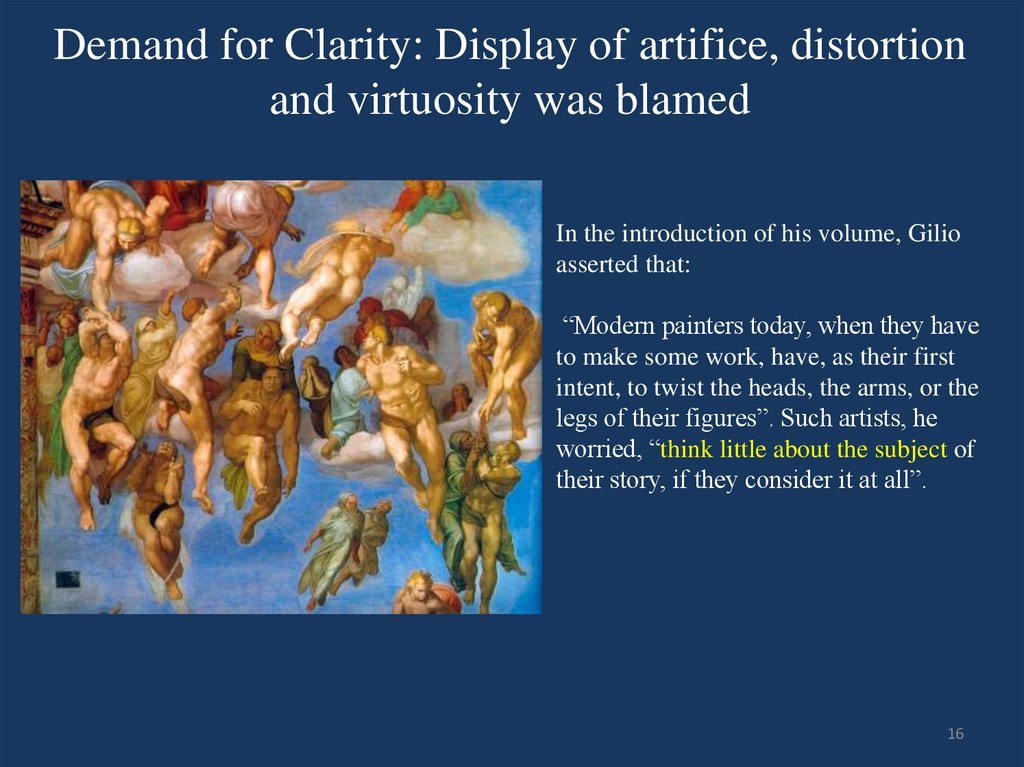

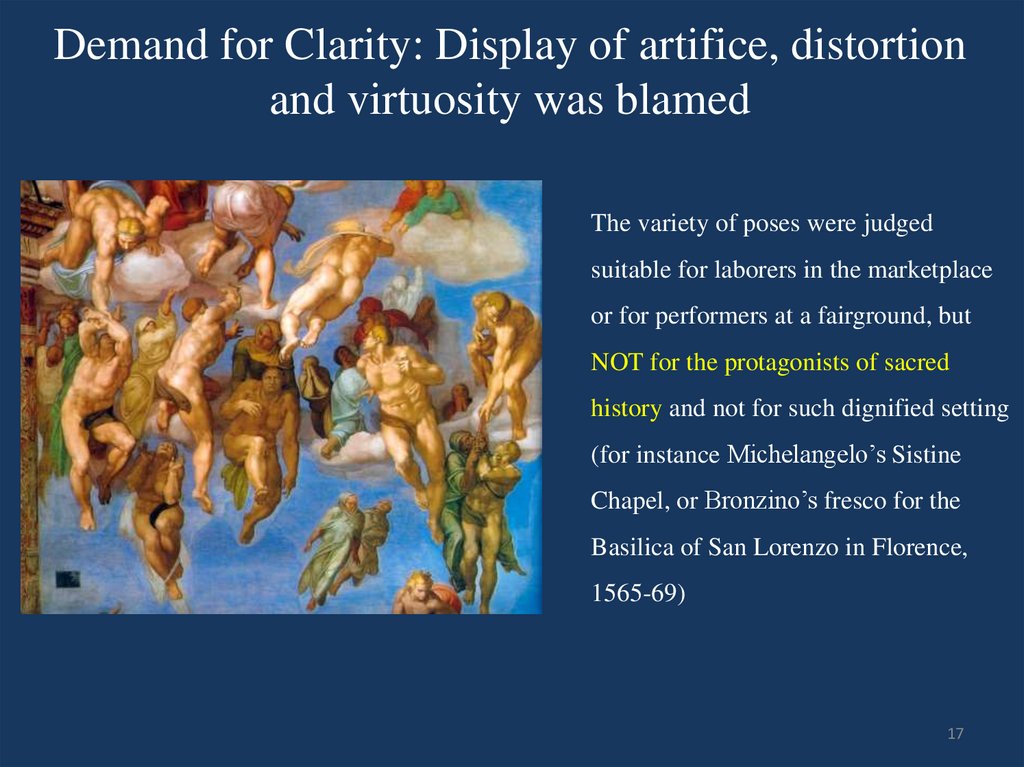

7. Demand for Clarity: Display of artifice, distortion and virtuosity was blamed

78.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Hc08dgjLr

M

8

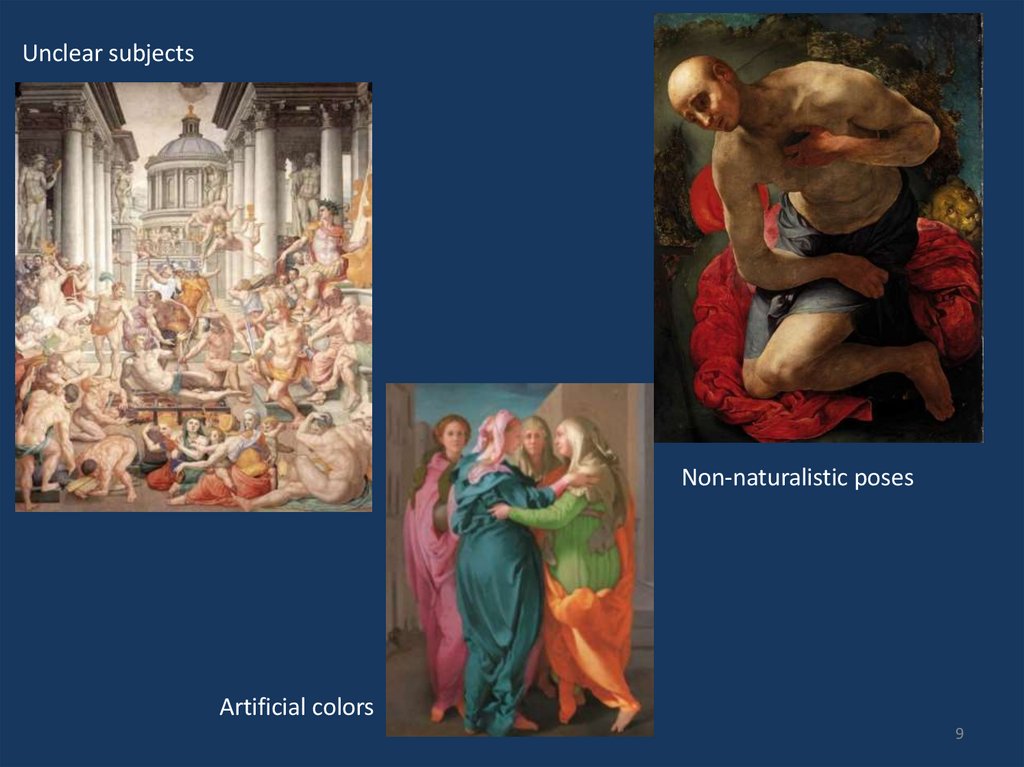

9.

Unclear subjectsNon-naturalistic poses

Artificial colors

9

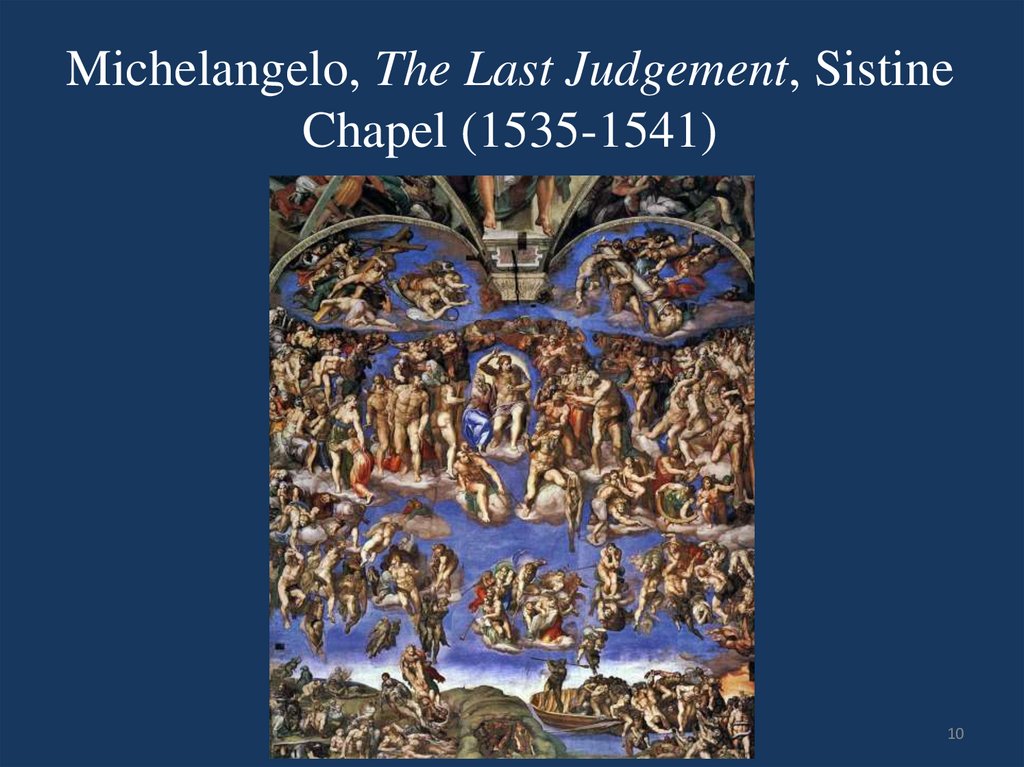

10. Michelangelo, The Last Judgement, Sistine Chapel (1535-1541)

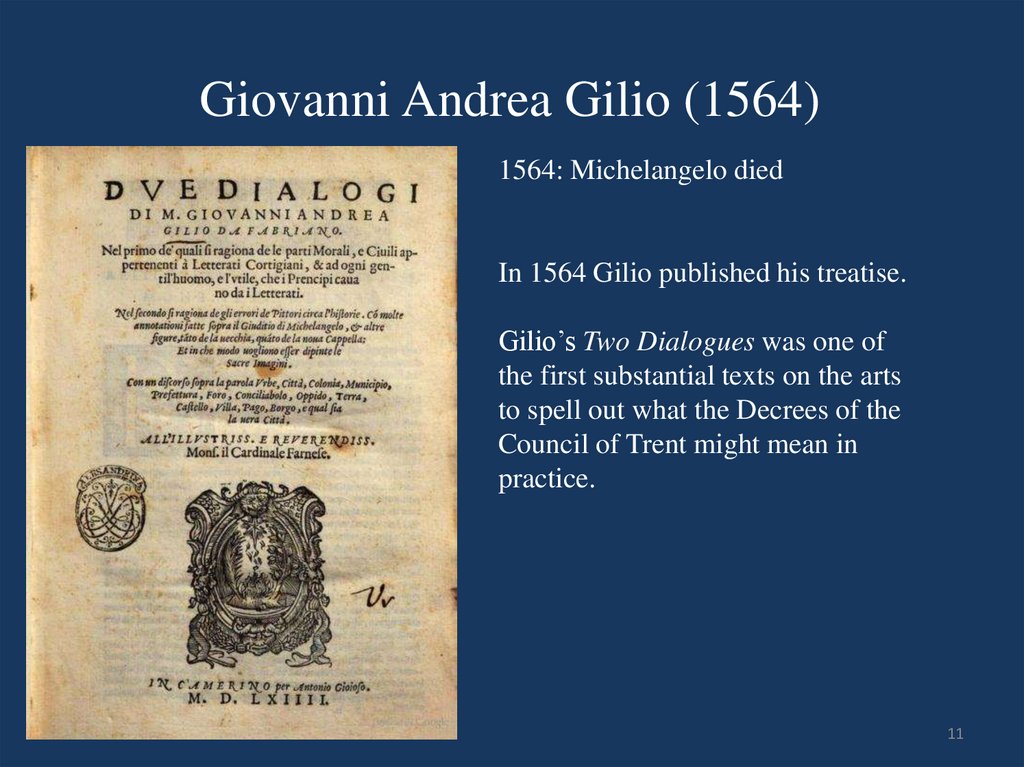

1011. Giovanni Andrea Gilio (1564)

1564: Michelangelo diedIn 1564 Gilio published his treatise.

Gilio’s Two Dialogues was one of

the first substantial texts on the arts

to spell out what the Decrees of the

Council of Trent might mean in

practice.

11

12. Giovanni Andrea Gilio (1564)

For Gilio:This kind of painting was not mere ornament or diversion, but an

instrument for making the truth visible.

It had to be clear, easy to understand by both the learned and the unlearned

and could not deviate in any particular form from authoritative texts or

established pictorial conventions (decorum).

Michelangelo erred greatly, according to Gilio, by incorporating such

figures as Minos and Charon, inventions that came from the poets Dante

and Virgil, rather than from scriptural sources.

12

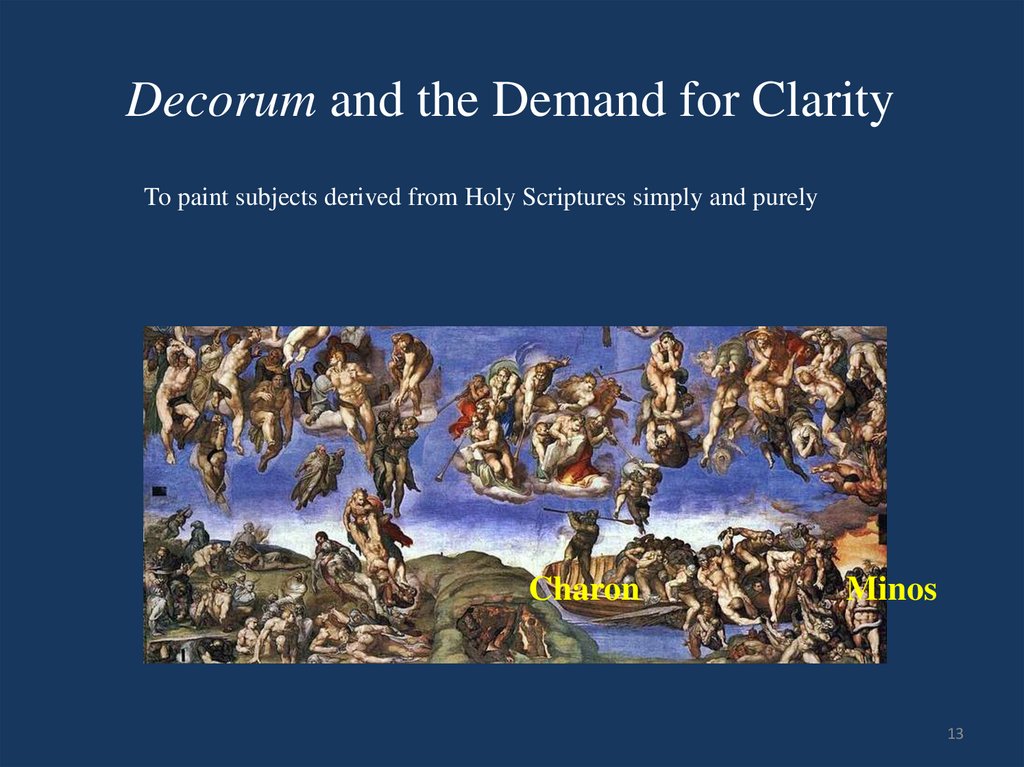

13. Decorum and the Demand for Clarity

To paint subjects derived from Holy Scriptures simply and purelyCharon

Minos

13

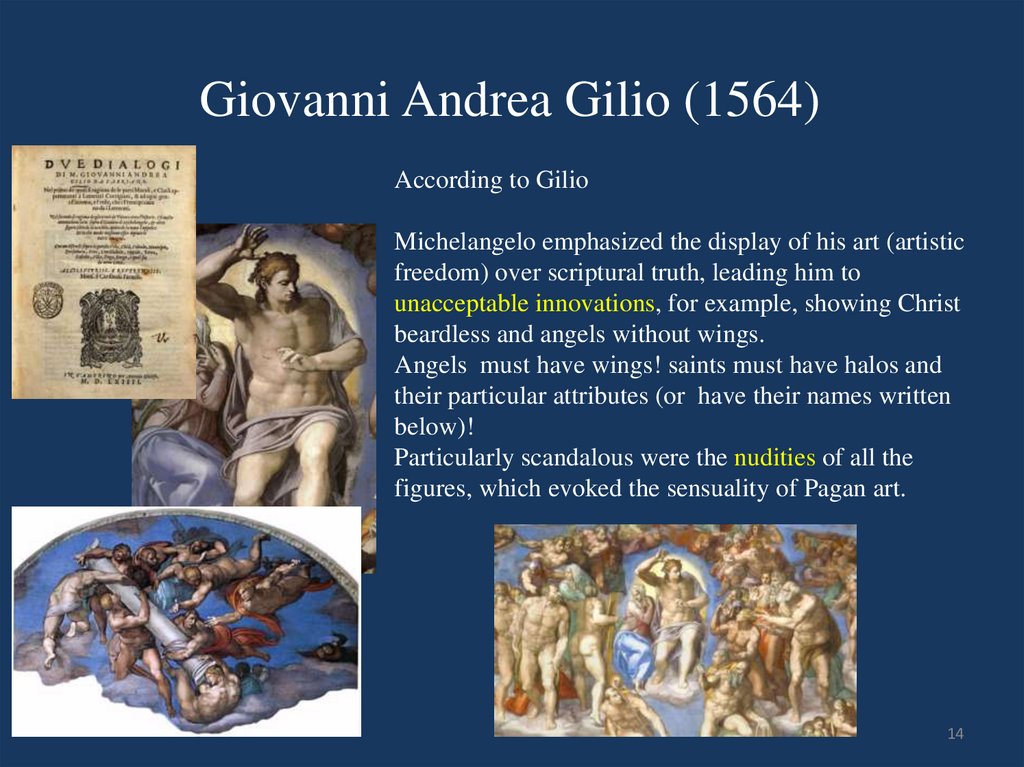

14. Giovanni Andrea Gilio (1564)

According to GilioMichelangelo emphasized the display of his art (artistic

freedom) over scriptural truth, leading him to

unacceptable innovations, for example, showing Christ

beardless and angels without wings.

Angels must have wings! saints must have halos and

their particular attributes (or have their names written

below)!

Particularly scandalous were the nudities of all the

figures, which evoked the sensuality of Pagan art.

14

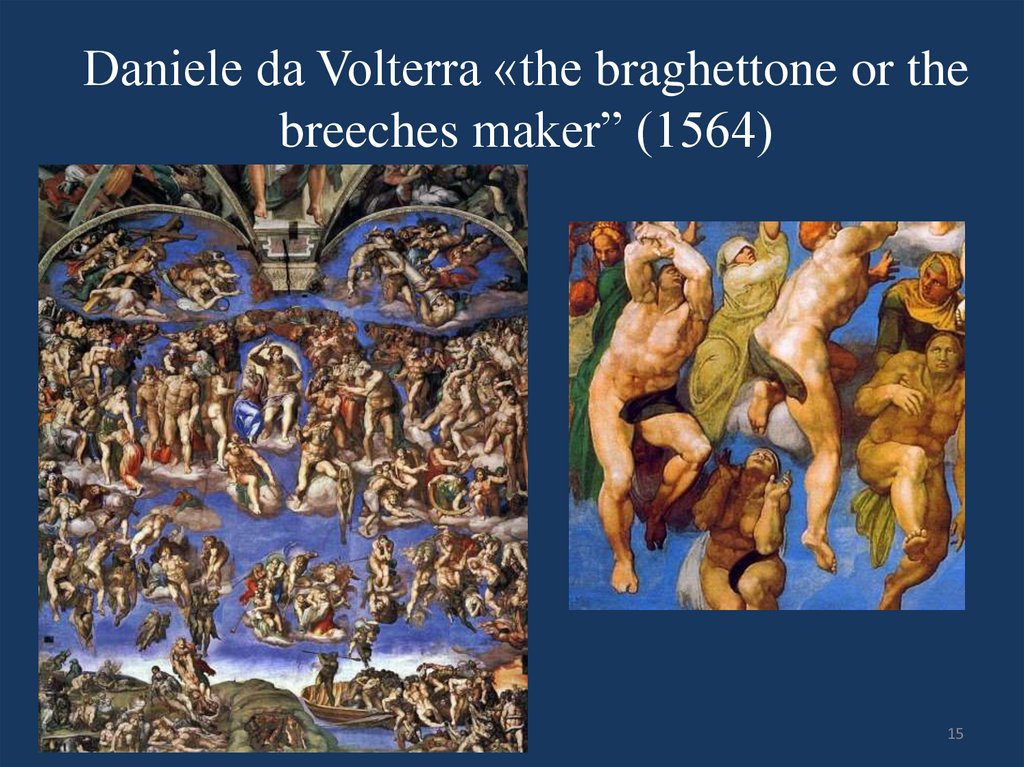

15. Daniele da Volterra «the braghettone or the breeches maker” (1564)

1516. Demand for Clarity: Display of artifice, distortion and virtuosity was blamed

In the introduction of his volume, Gilioasserted that:

“Modern painters today, when they have

to make some work, have, as their first

intent, to twist the heads, the arms, or the

legs of their figures”. Such artists, he

worried, “think little about the subject of

their story, if they consider it at all”.

16

17. Demand for Clarity: Display of artifice, distortion and virtuosity was blamed

The variety of poses were judgedsuitable for laborers in the marketplace

or for performers at a fairground, but

NOT for the protagonists of sacred

history and not for such dignified setting

(for instance Michelangelo’s Sistine

Chapel, or Bronzino’s fresco for the

Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence,

1565-69)

17

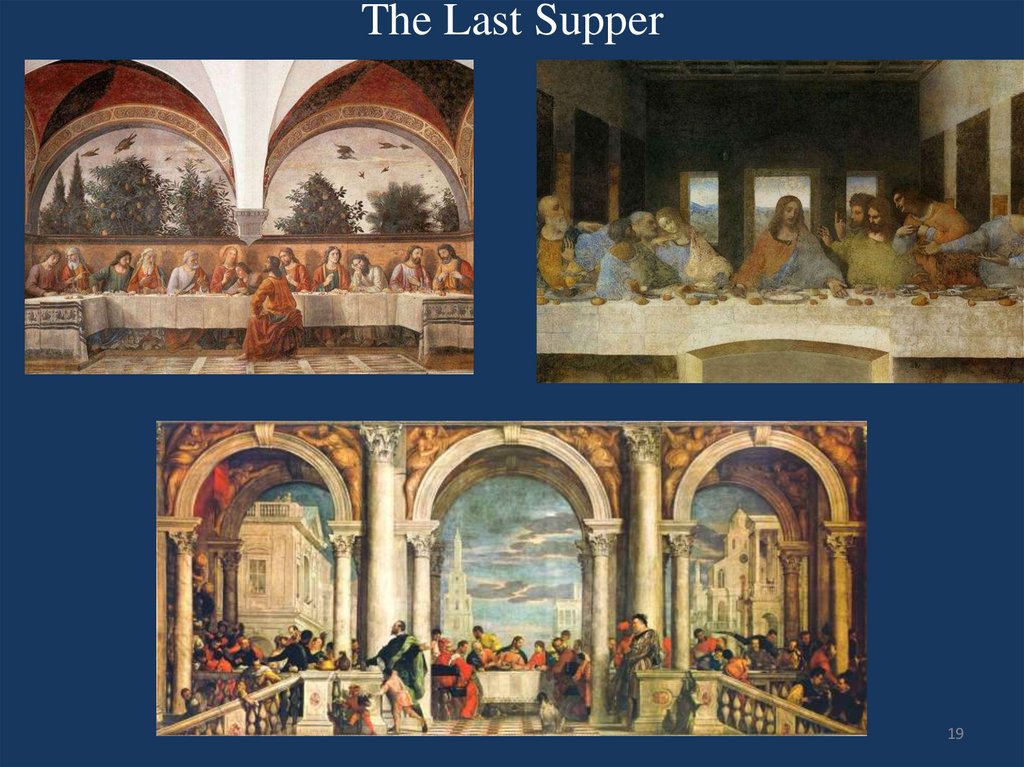

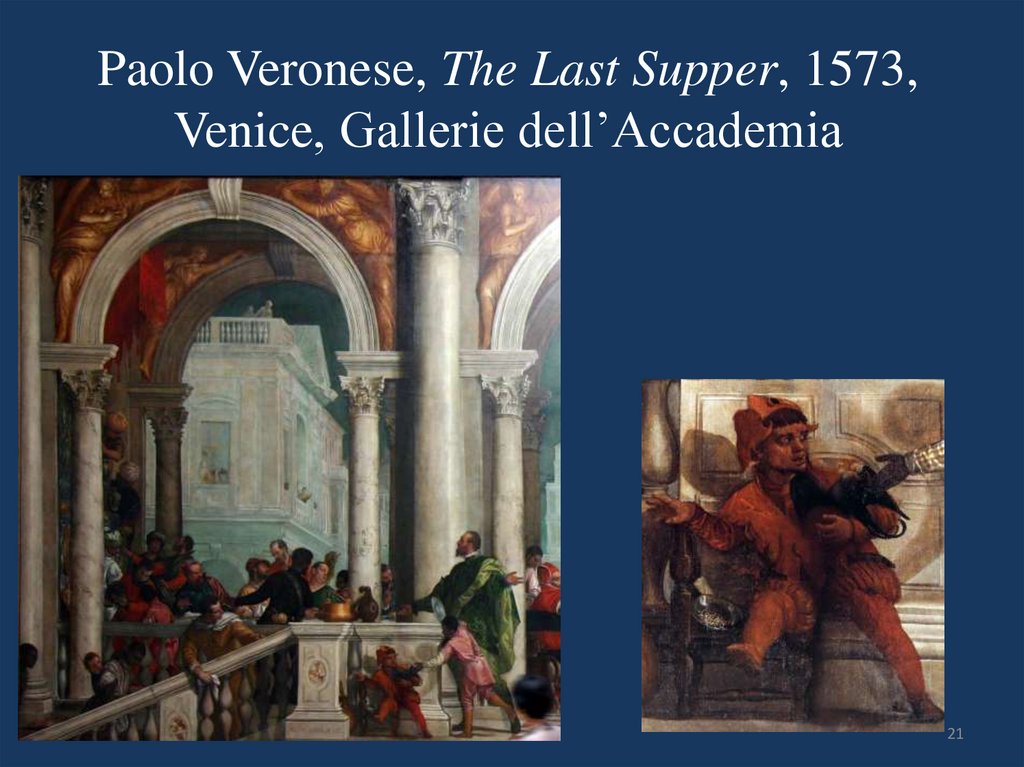

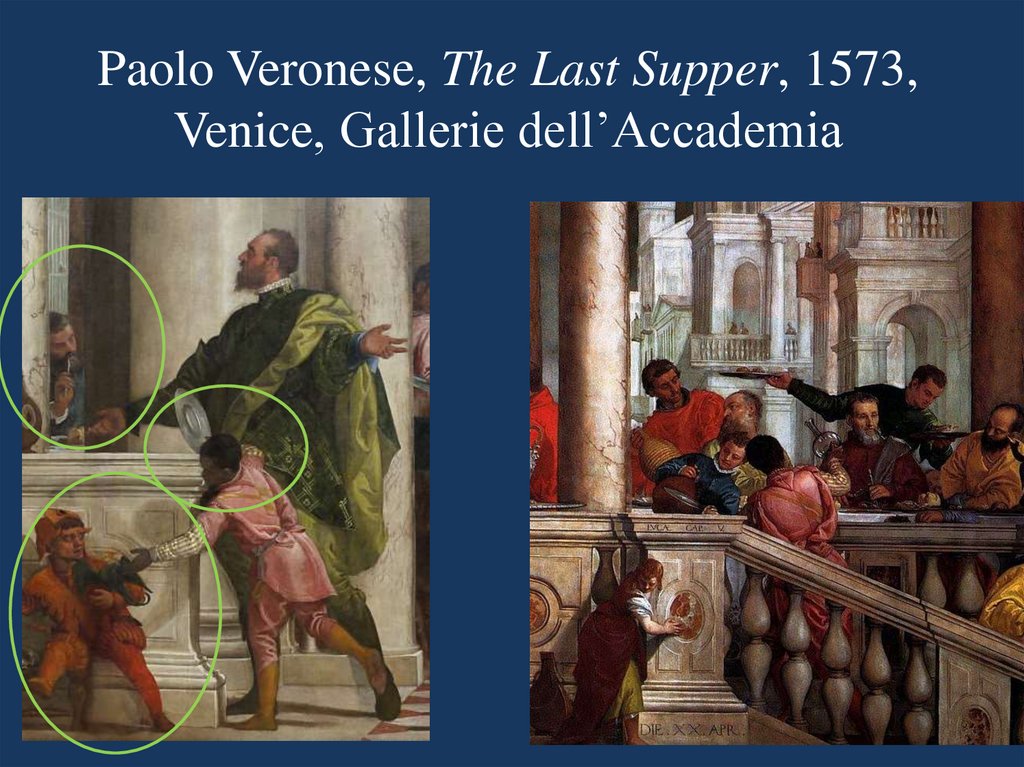

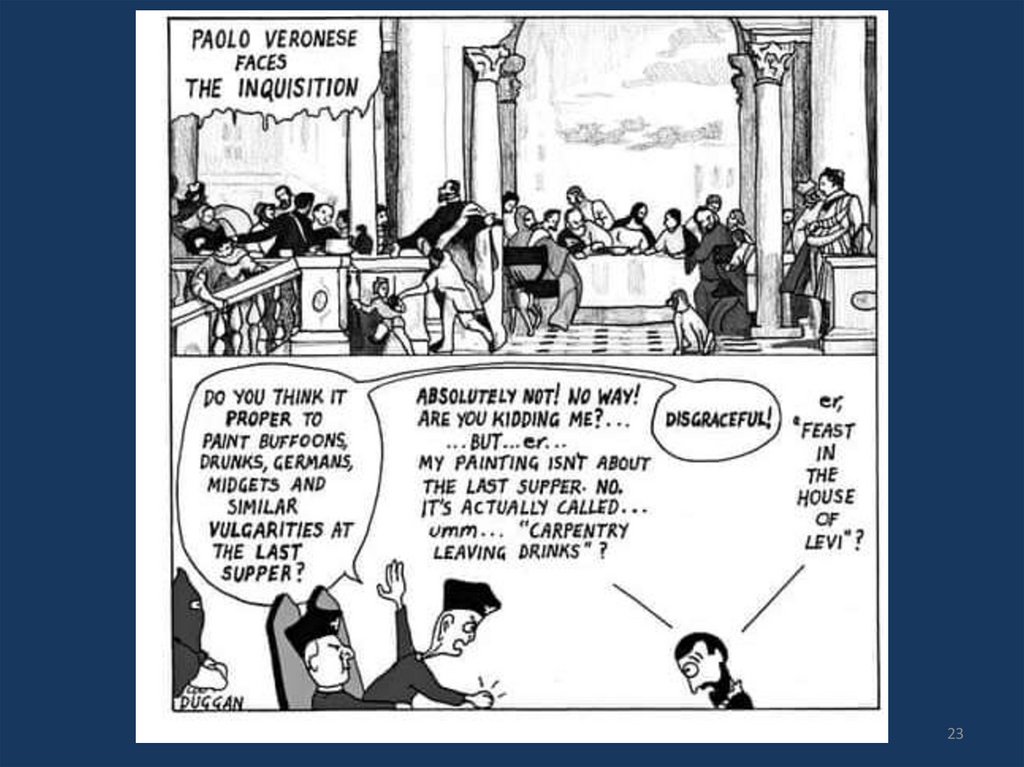

18. Paolo Veronese, The Last Supper (formerly), 1573, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia

1819. The Last Supper

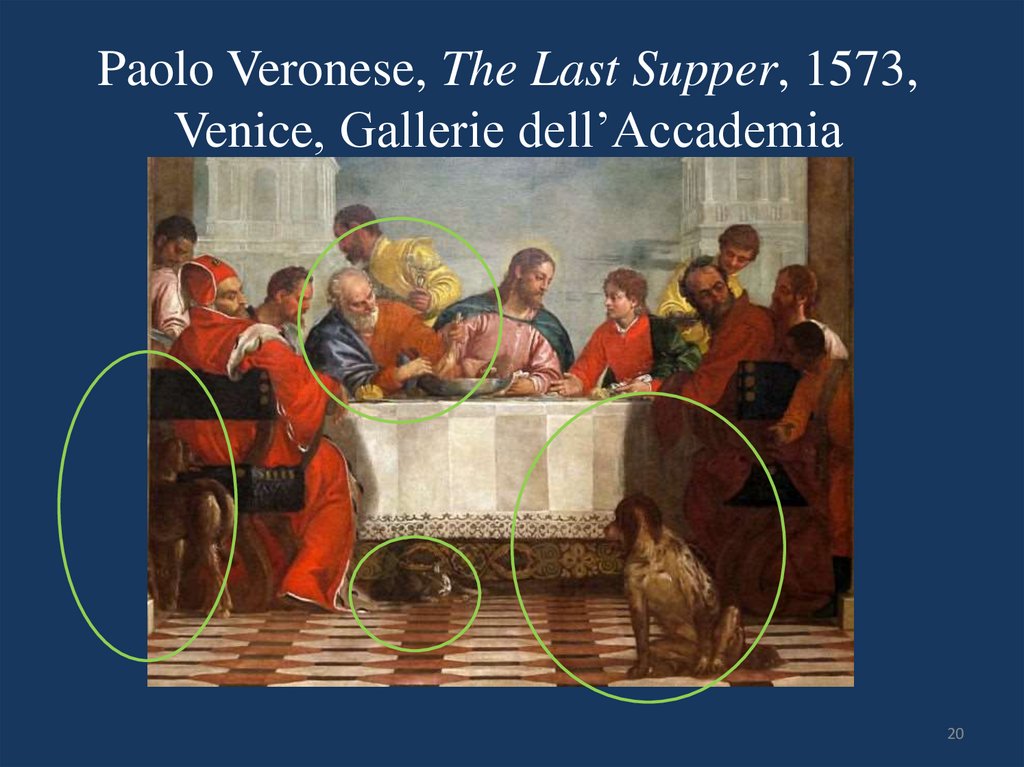

1920. Paolo Veronese, The Last Supper, 1573, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia

2021. Paolo Veronese, The Last Supper, 1573, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia

2122. Paolo Veronese, The Last Supper, 1573, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia

2223.

2324. Gabriele Paleotti, 1582

•“Everyday one sees, especially in the churches,pictures so obscure and ambiguous that while they

should, by illuminating the intellect, encourage

devotion and touch the heart, their obscurity

confounds the mind, distracting it in a thousand

ways, and keeping it occupied in trying to decide

which figure is what”.

Paleotti summed up the duties of a good Catholic

artist in three Latin words:

Docère (to teach)

Delectare (to delight)

Movère (to move)

24

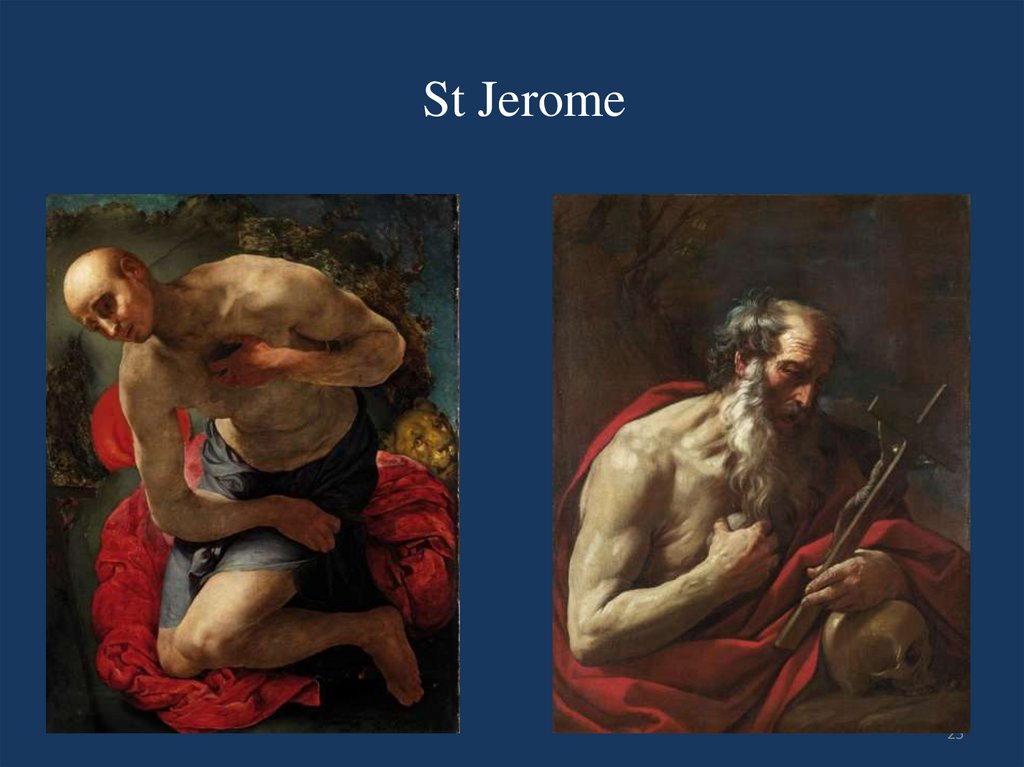

25. St Jerome

2526. St Mary Magdalene

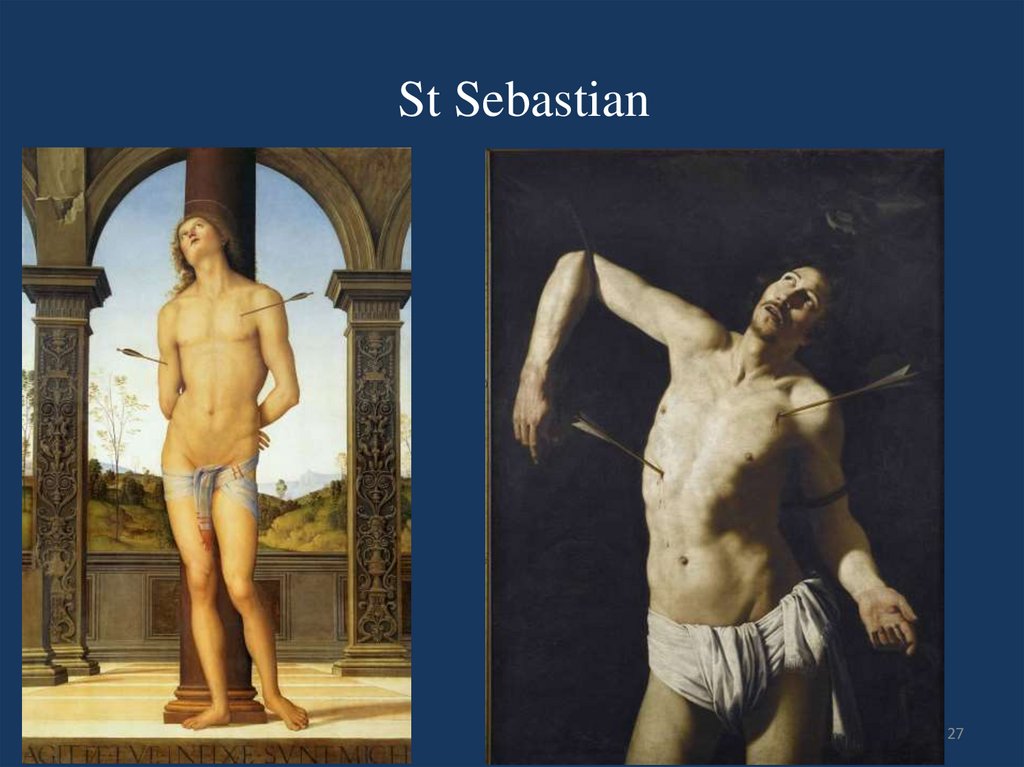

2627. St Sebastian

2728. Bologna

Bologna, a walled medieval city, that waspart of the Papal States and governed by a

Senate with close political ties to Rome

28

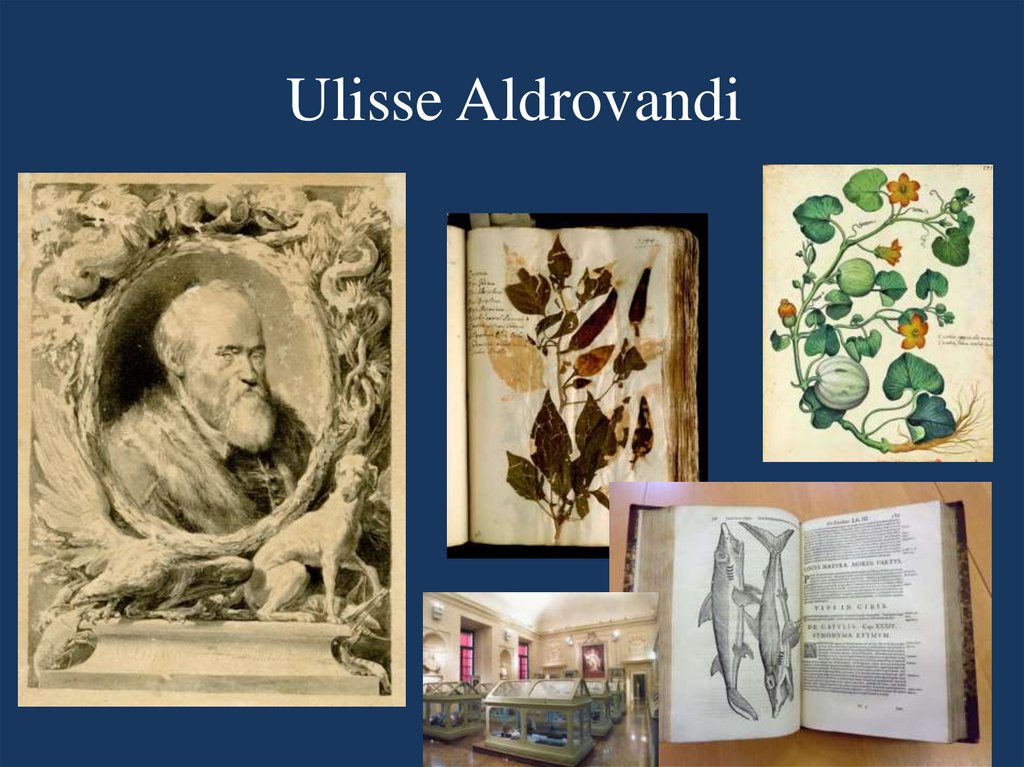

29. Ulisse Aldrovandi

2930. Ulisse Aldrovandi

https://amshistorica.unibo.it/aldrovandimanoscrittihttps://amshistorica.unibo.it/ulissealdrovandiopereastampa

30

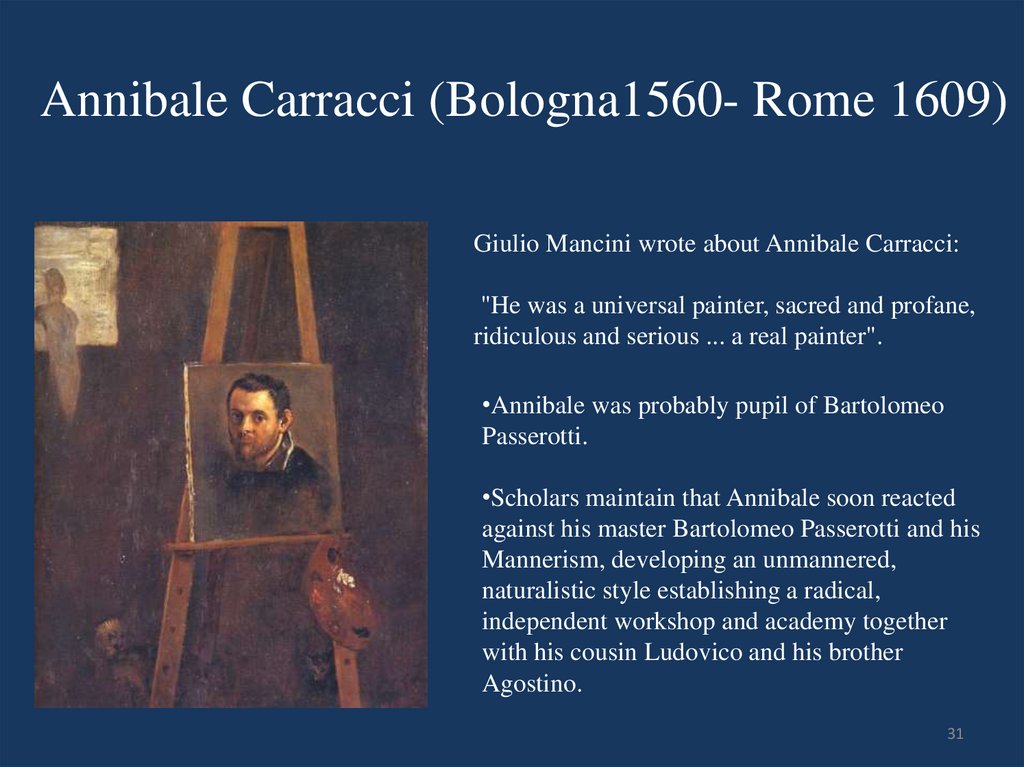

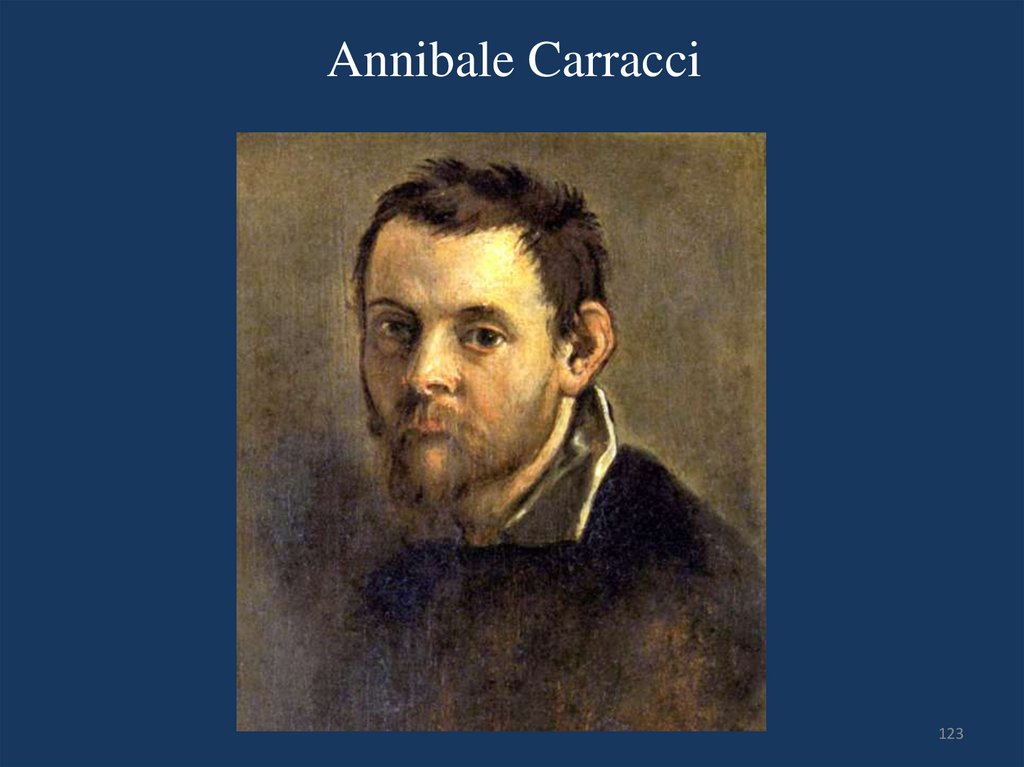

31. Annibale Carracci (Bologna1560- Rome 1609)

Giulio Mancini wrote about Annibale Carracci:"He was a universal painter, sacred and profane,

ridiculous and serious ... a real painter".

•Annibale was probably pupil of Bartolomeo

Passerotti.

•Scholars maintain that Annibale soon reacted

against his master Bartolomeo Passerotti and his

Mannerism, developing an unmannered,

naturalistic style establishing a radical,

independent workshop and academy together

with his cousin Ludovico and his brother

Agostino.

31

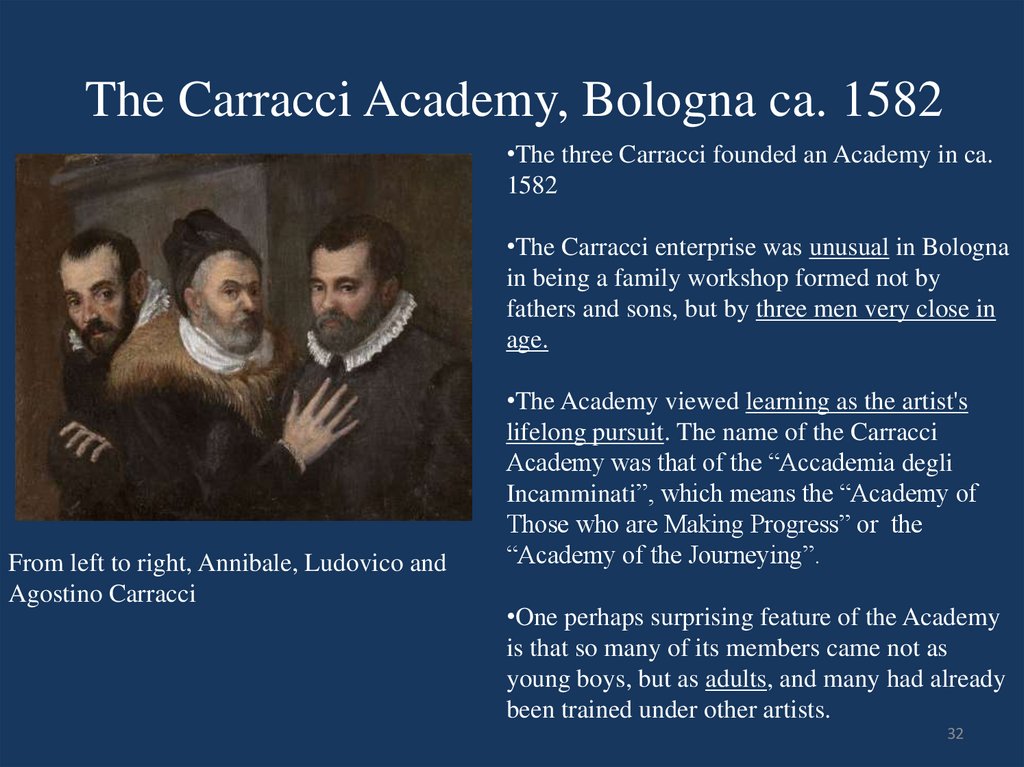

32. The Carracci Academy, Bologna ca. 1582

•The three Carracci founded an Academy in ca.1582

•The Carracci enterprise was unusual in Bologna

in being a family workshop formed not by

fathers and sons, but by three men very close in

age.

From left to right, Annibale, Ludovico and

Agostino Carracci

•The Academy viewed learning as the artist's

lifelong pursuit. The name of the Carracci

Academy was that of the “Accademia degli

Incamminati”, which means the “Academy of

Those who are Making Progress” or the

“Academy of the Journeying”.

•One perhaps surprising feature of the Academy

is that so many of its members came not as

young boys, but as adults, and many had already

been trained under other artists.

32

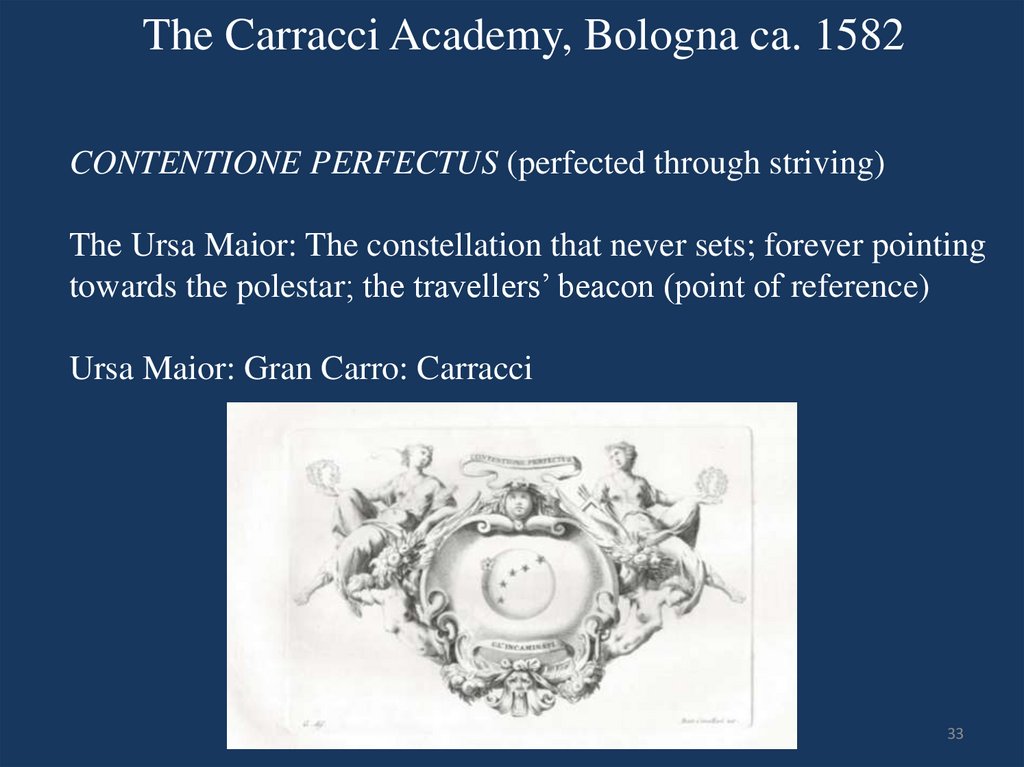

33. The Carracci Academy, Bologna ca. 1582

CONTENTIONE PERFECTUS (perfected through striving)The Ursa Maior: The constellation that never sets; forever pointing

towards the polestar; the travellers’ beacon (point of reference)

Ursa Maior: Gran Carro: Carracci

33

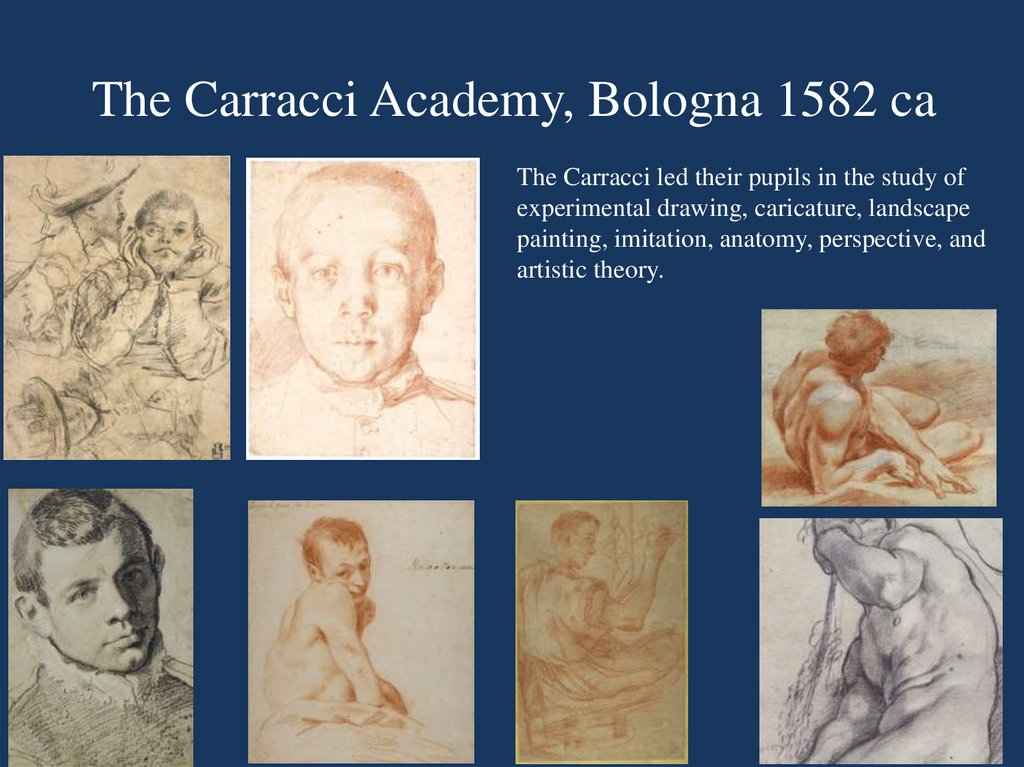

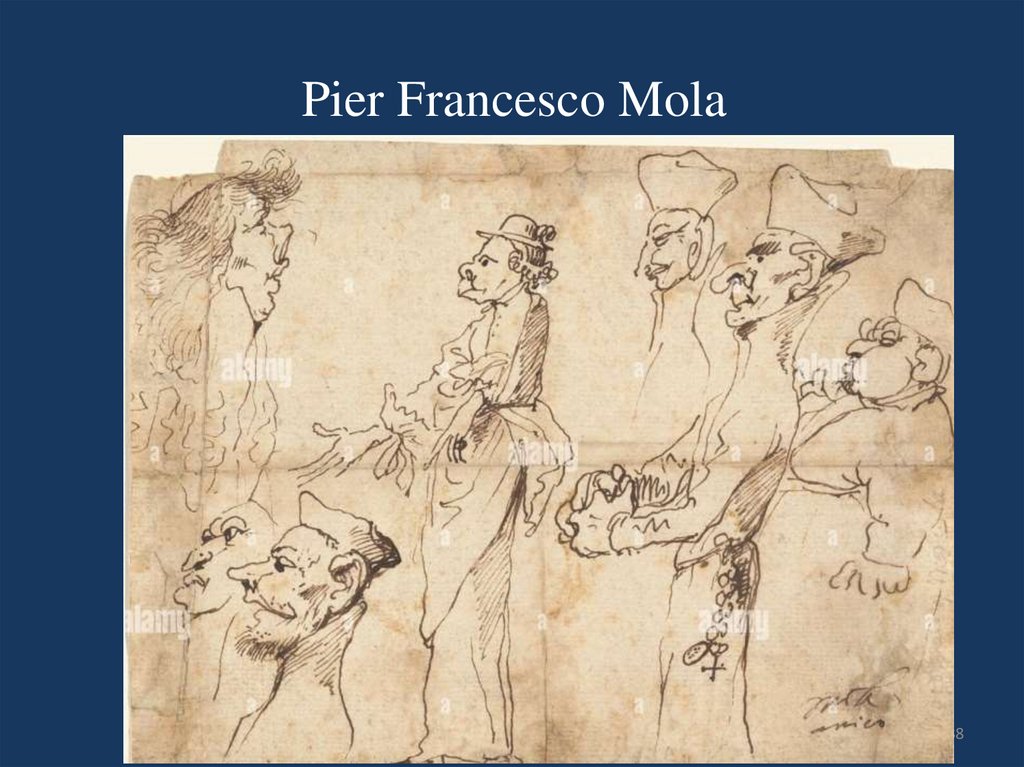

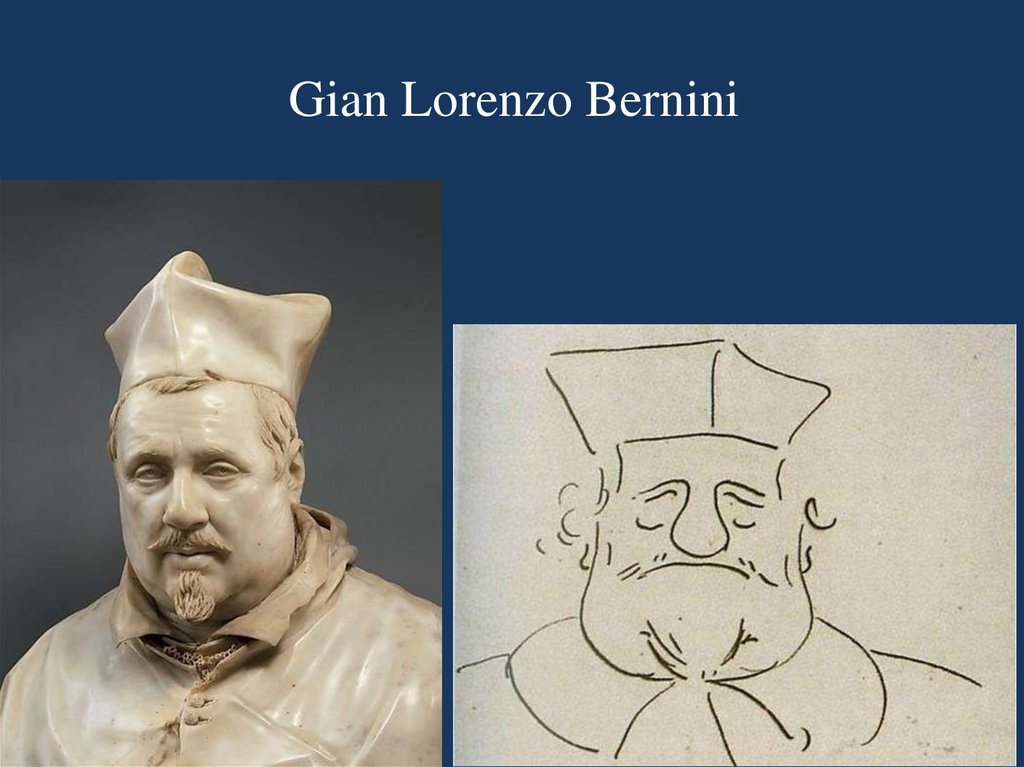

34. The Carracci Academy, Bologna 1582 ca

The Carracci led their pupils in the study ofexperimental drawing, caricature, landscape

painting, imitation, anatomy, perspective, and

artistic theory.

34

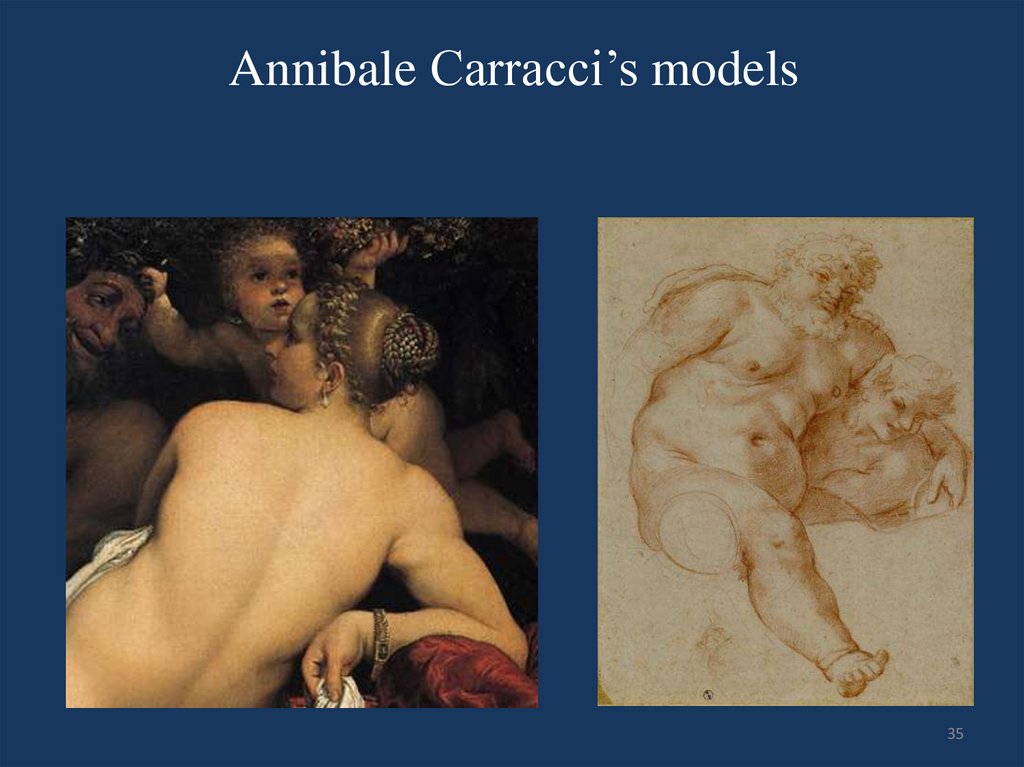

35. Annibale Carracci’s models

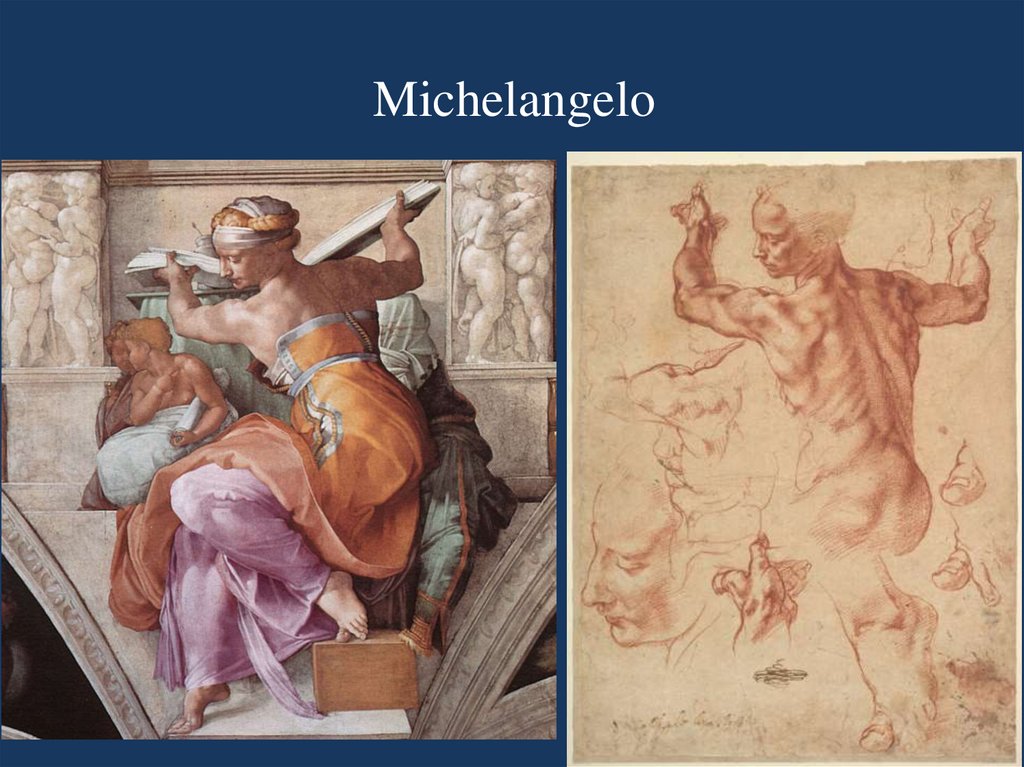

3536. Michelangelo

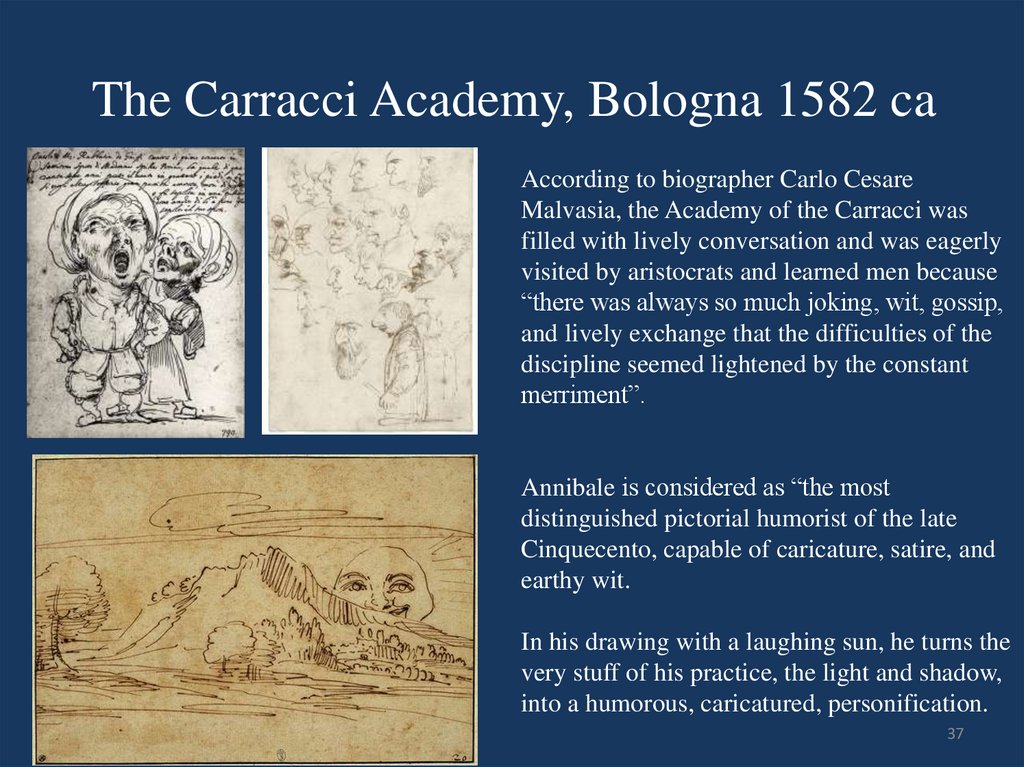

3637. The Carracci Academy, Bologna 1582 ca

According to biographer Carlo CesareMalvasia, the Academy of the Carracci was

filled with lively conversation and was eagerly

visited by aristocrats and learned men because

“there was always so much joking, wit, gossip,

and lively exchange that the difficulties of the

discipline seemed lightened by the constant

merriment”.

Annibale is considered as “the most

distinguished pictorial humorist of the late

Cinquecento, capable of caricature, satire, and

earthy wit.

In his drawing with a laughing sun, he turns the

very stuff of his practice, the light and shadow,

into a humorous, caricatured, personification.

37

38. Pier Francesco Mola

3839. Gian Lorenzo Bernini

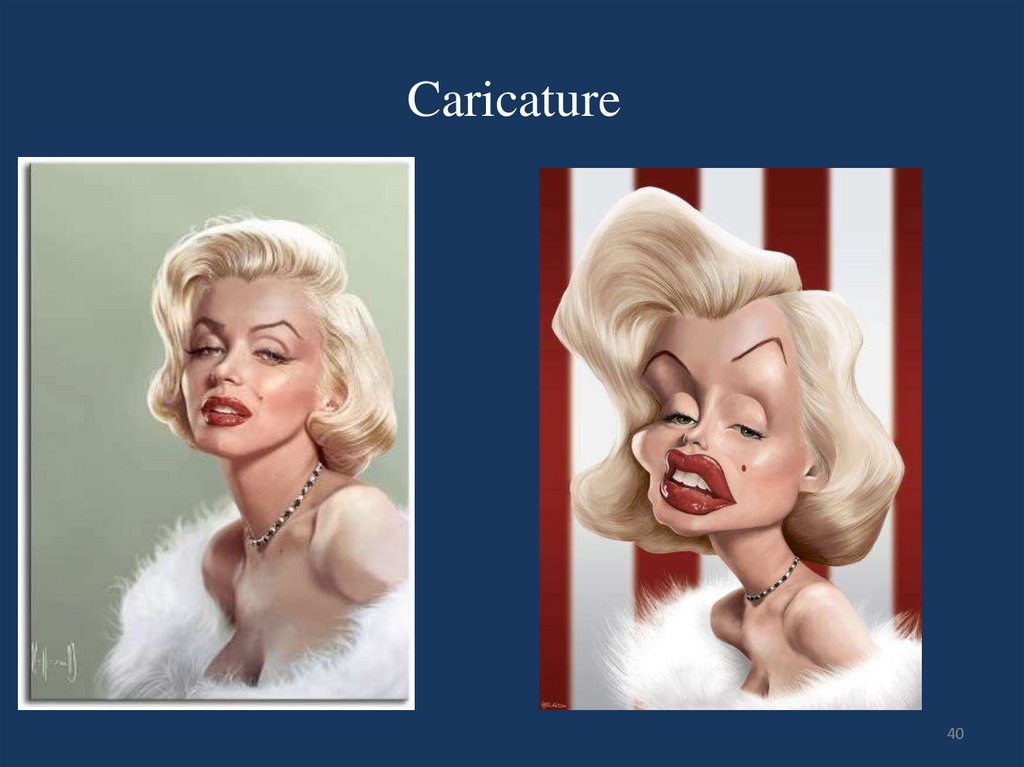

3940. Caricature

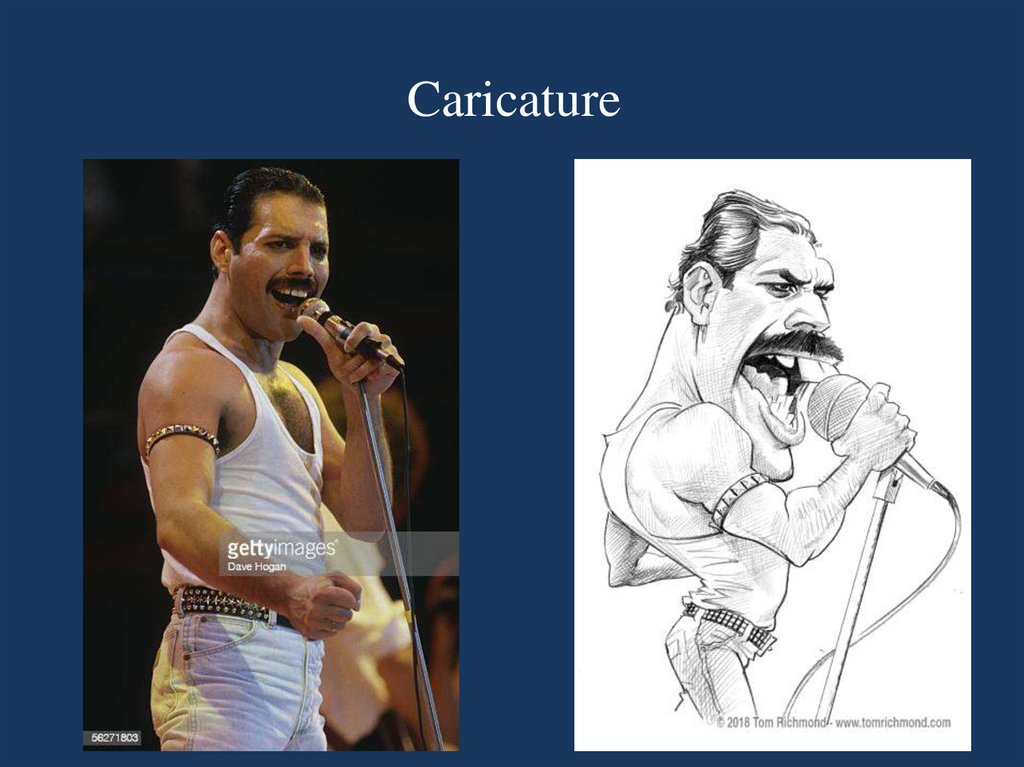

4041. Caricature

4142.

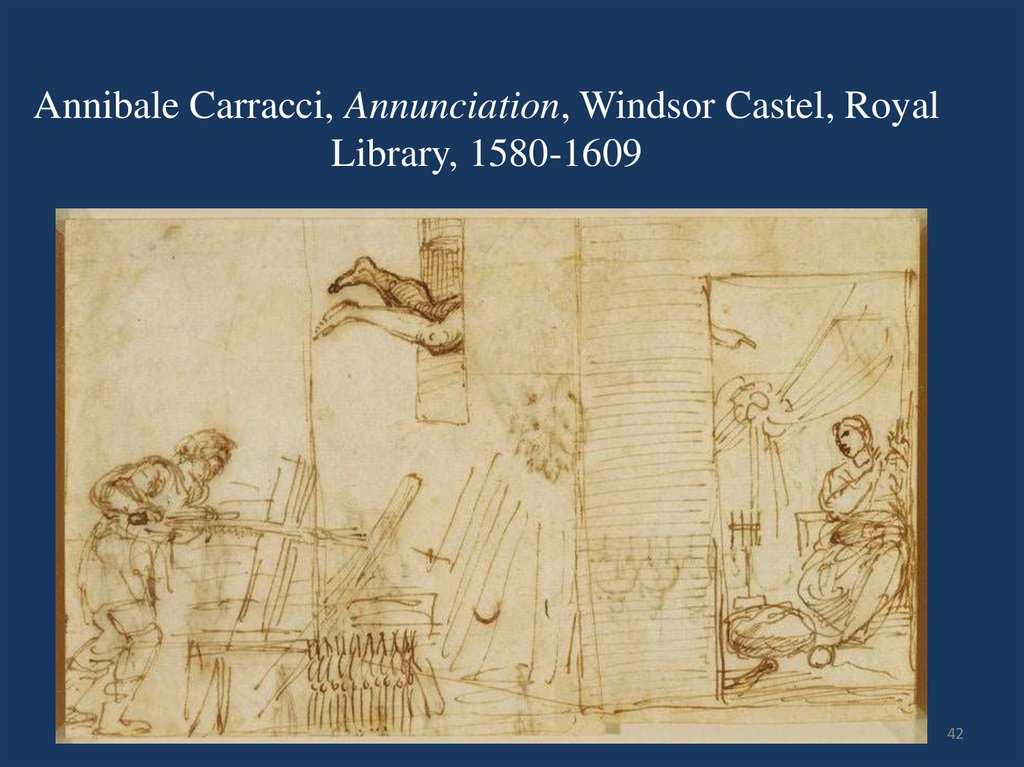

Annibale Carracci, Annunciation, Windsor Castel, RoyalLibrary, 1580-1609

42

43.

Annibale Carracci, Annunciation, Windsor Castel, RoyalLibrary, 1580-1609

A compositional study in which the

angel of the Annunciation flies

through a window and is partly

hidden by the wall of the house; only

the pointing hand and the legs are

visible.

43

44.

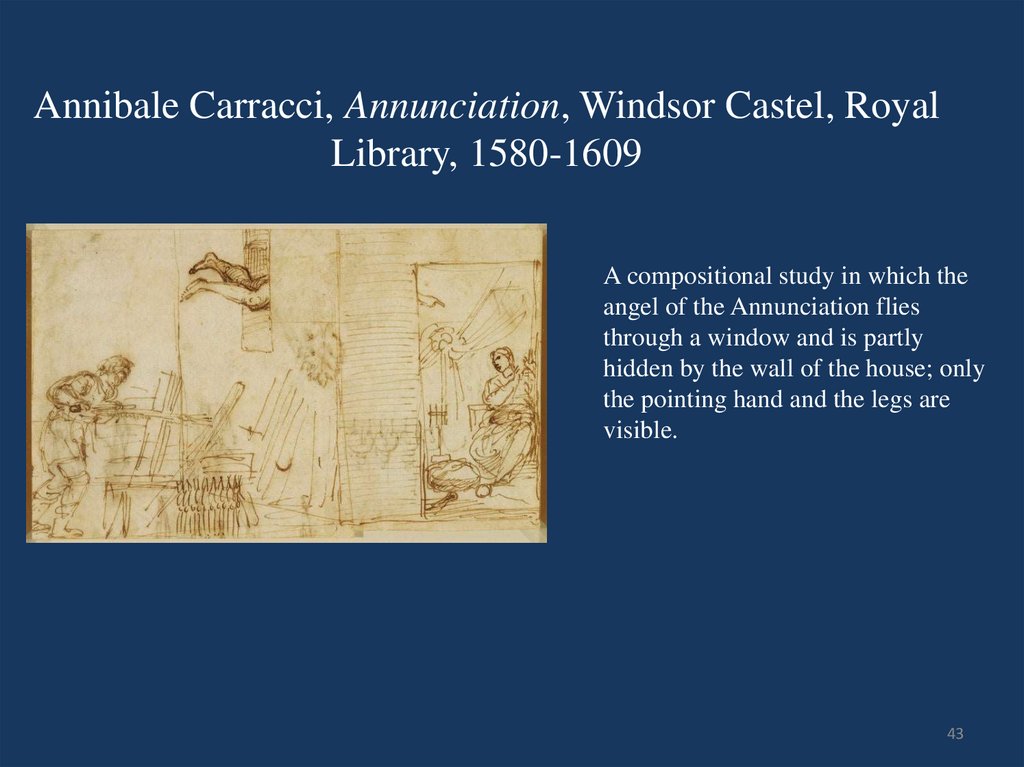

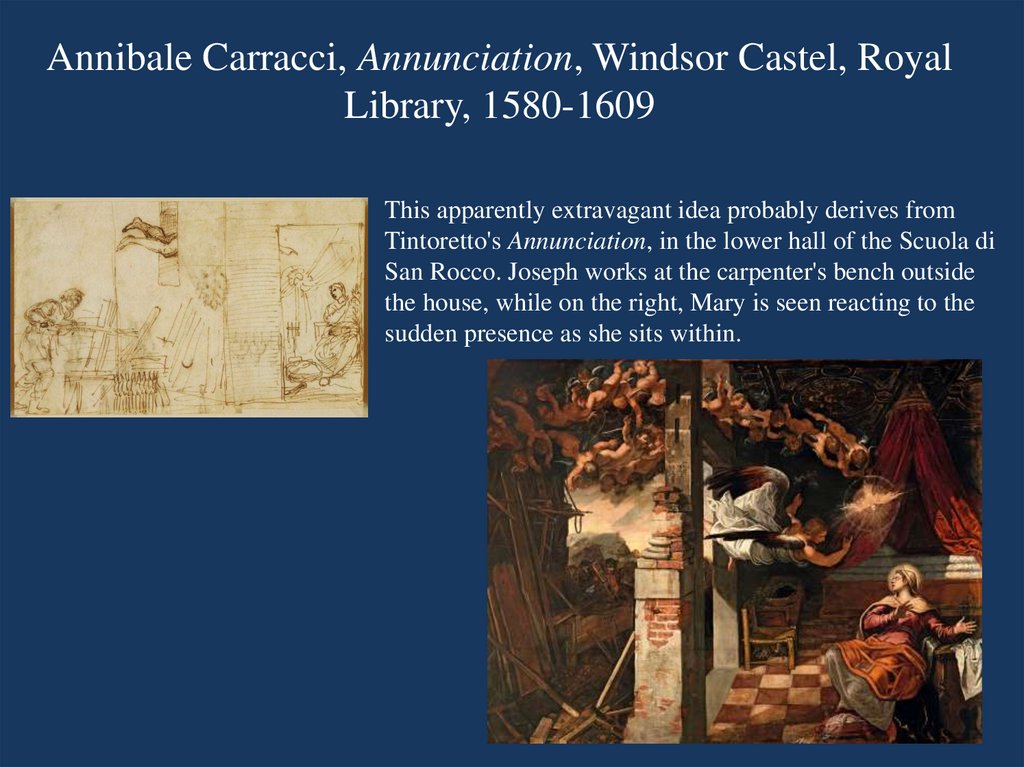

Annibale Carracci, Annunciation, Windsor Castel, RoyalLibrary, 1580-1609

This apparently extravagant idea probably derives from

Tintoretto's Annunciation, in the lower hall of the Scuola di

San Rocco. Joseph works at the carpenter's bench outside

the house, while on the right, Mary is seen reacting to the

sudden presence as she sits within.

44

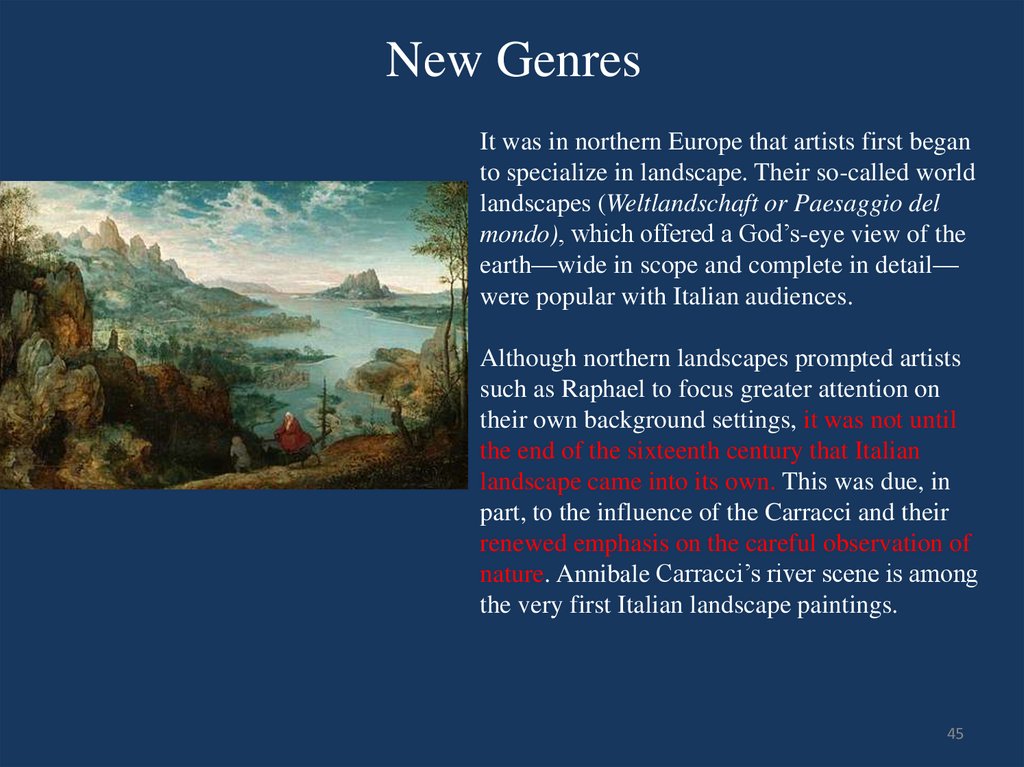

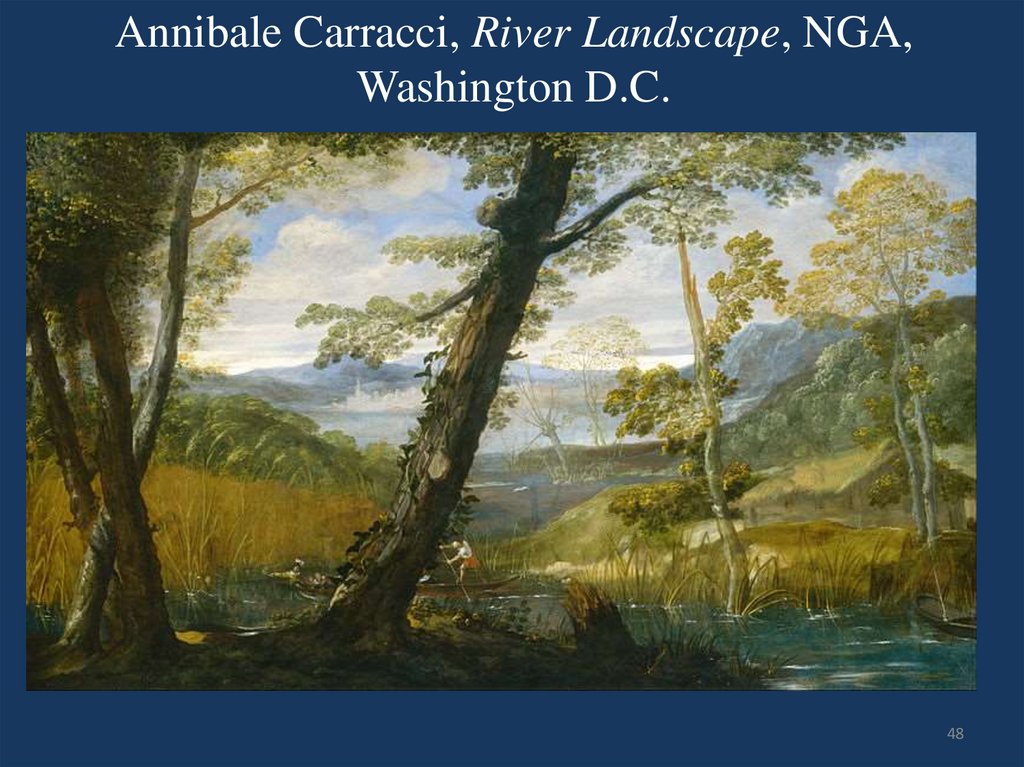

45. New Genres

It was in northern Europe that artists first beganto specialize in landscape. Their so-called world

landscapes (Weltlandschaft or Paesaggio del

mondo), which offered a God’s-eye view of the

earth—wide in scope and complete in detail—

were popular with Italian audiences.

Although northern landscapes prompted artists

such as Raphael to focus greater attention on

their own background settings, it was not until

the end of the sixteenth century that Italian

landscape came into its own. This was due, in

part, to the influence of the Carracci and their

renewed emphasis on the careful observation of

nature. Annibale Carracci’s river scene is among

the very first Italian landscape paintings.

45

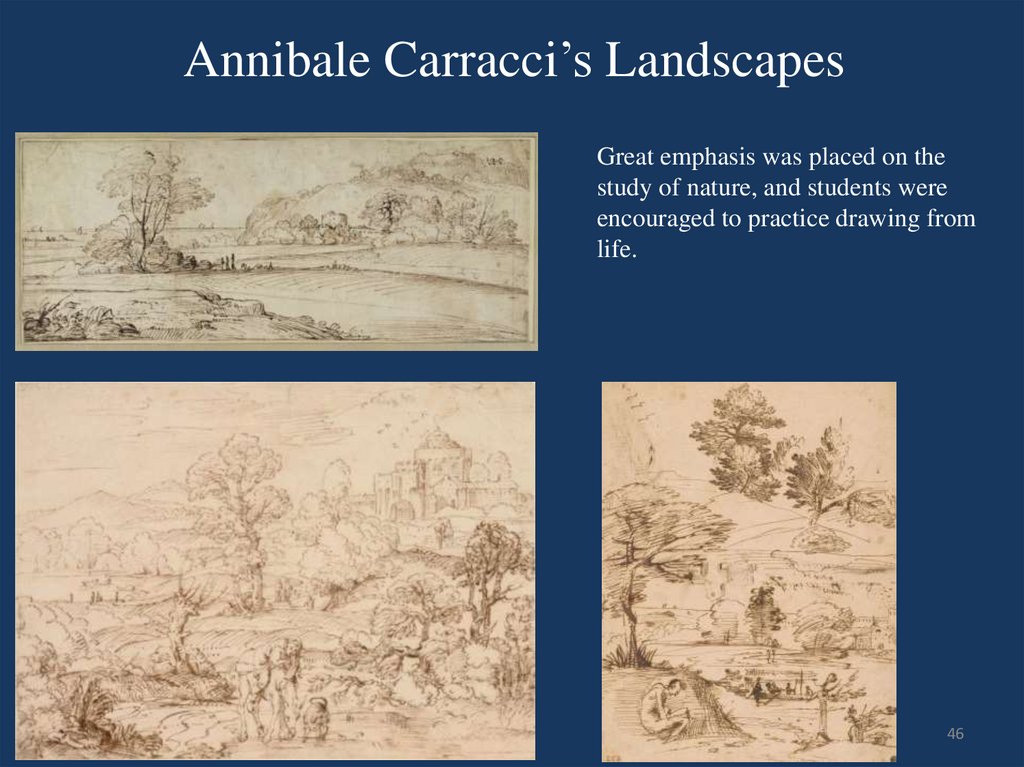

46. Annibale Carracci’s Landscapes

Great emphasis was placed on thestudy of nature, and students were

encouraged to practice drawing from

life.

46

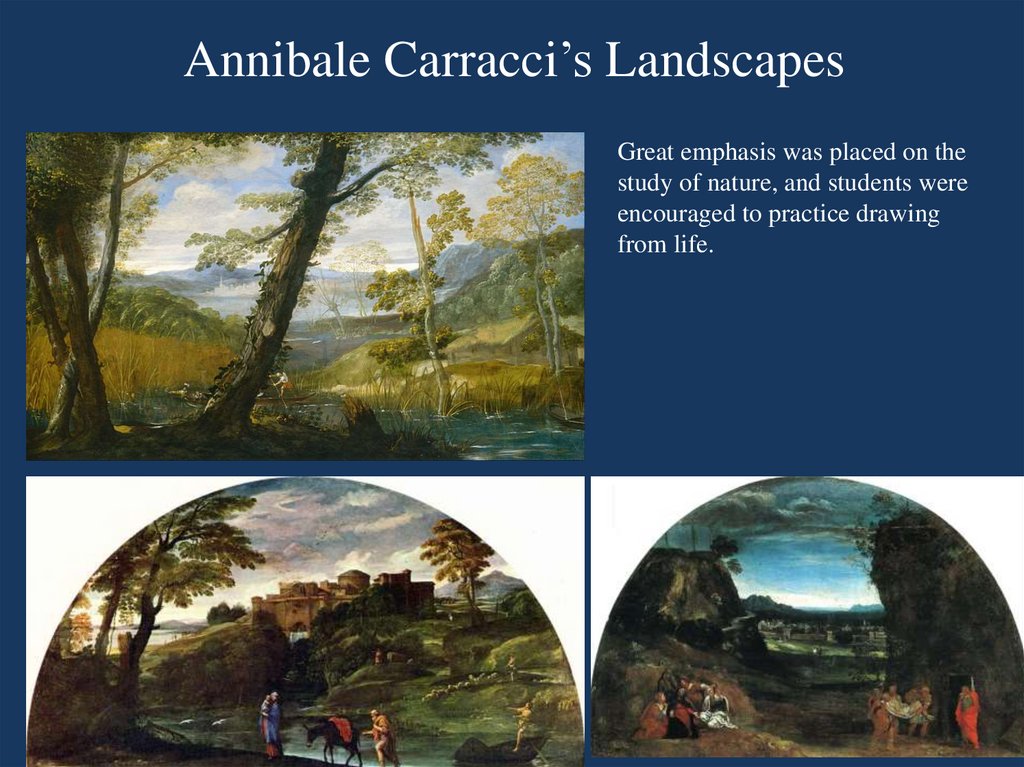

47. Annibale Carracci’s Landscapes

Great emphasis was placed on thestudy of nature, and students were

encouraged to practice drawing

from life.

47

48. Annibale Carracci, River Landscape, NGA, Washington D.C.

4849. Annibale Carracci, River Landscape, NGA, Washington D.C.

https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.41673.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v

=aKyyxpzUIYk&t=294s

https://www.nga.gov/content/dam

/ngaweb/research/publications/pdf

s/italian-paintings-17th-and-18thcenturies.pdf

49

50. Annibale Carracci, River Landscape, NGA, Washington D.C.

It might be said that with paintings like this one, Annibale Carracciinvented the landscape as a subject for Italian baroque painting.

Nature here is appreciated first and foremost for herself and not as the

backdrop for a story. A mellow sunlight dapples the land and picks out

the ripples disturbing the surface of the river. The gold in the treetops

suggests a day in early autumn. Brightly clad in red and white, a

boatman poles his craft through the shallow water.

In the company of his brother Agostino and his cousin Lodovico

Carracci, Annibale made excursions into the country in order to sketch

the landscape. From these quick studies made on the spot he worked

up his paintings in the studio. The resulting composition is an artful

balancing of forms.

50

51. Annibale Carracci, River Landscape, NGA, Washington D.C.

The repoussoir device of the dark foreground plane defined by treesenframes the scenes, which then recede in depth by means of

diminishing tonal gradations in zigzag patterns: brown and

yellowgreen earth tones in the foreground subside to lighter blues and

whites for the distant hills and plains.

In Bolognese palaces of the late sixteenth century landscapes appear

as decorative elements placed high on the walls; Posner has since

suggested that the River Landscape was intended as an overdoor.

51

52. New Genres

The late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw the emergence of new types of painting inItaly. For the first time since antiquity, landscape, still life, and genre pictures all became

established as independent subjects worthy of attention by the finest artists. Elements of

these had always been present in other kinds of pictures: landscape backdrops were

prominent, for example, in depictions of the Flight into Egypt and other religious subjects.

52

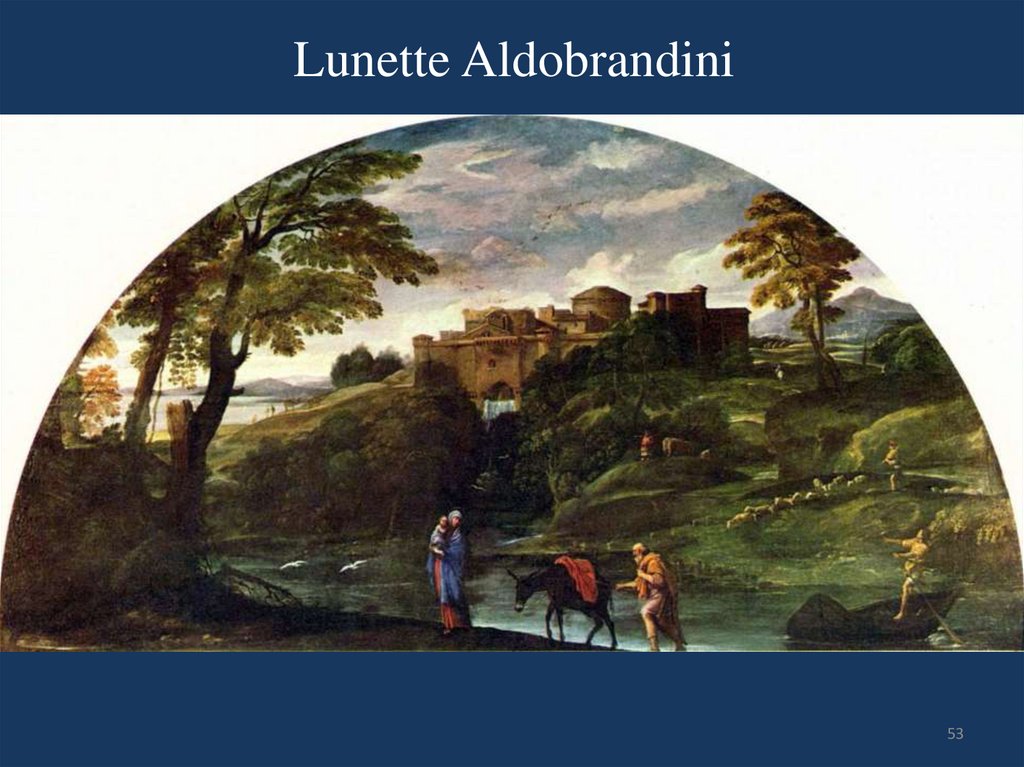

53. Lunette Aldobrandini

5354. Ludovico Carracci, Annunciation, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, 1584

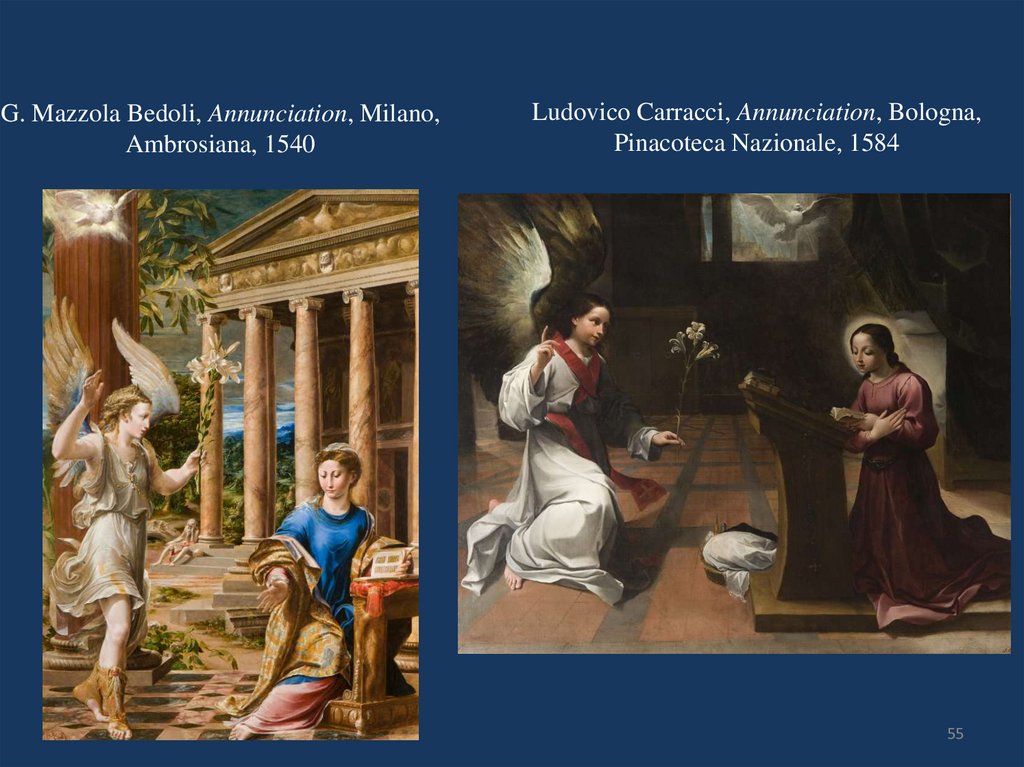

5455. Ludovico Carracci, Annunciation, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, 1584

G. Mazzola Bedoli, Annunciation, Milano,Ambrosiana, 1540

Ludovico Carracci, Annunciation, Bologna,

Pinacoteca Nazionale, 1584

55

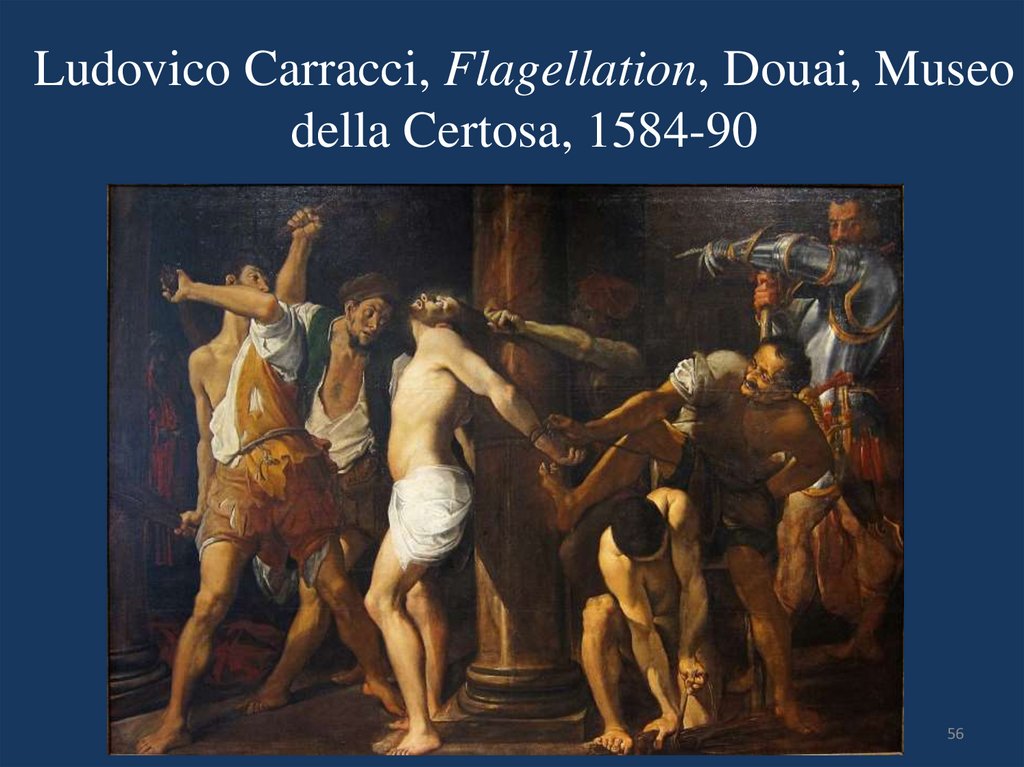

56. Ludovico Carracci, Flagellation, Douai, Museo della Certosa, 1584-90

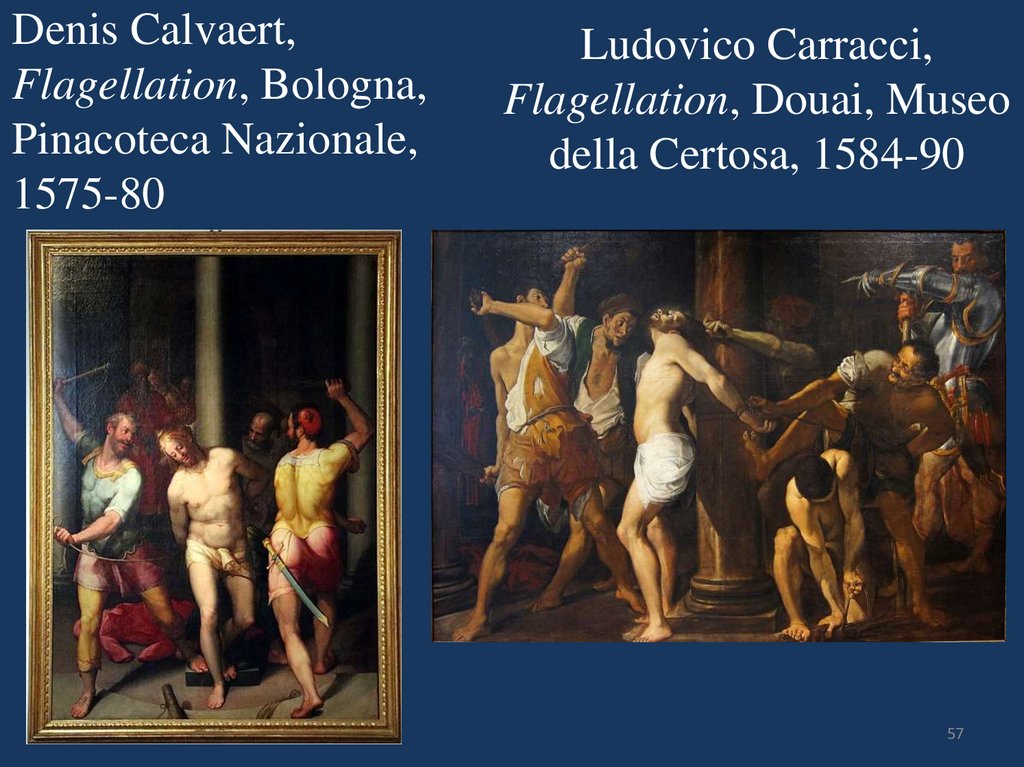

5657. Ludovico Carracci, Flagellation, Douai, Museo della Certosa, 1584-90

Denis Calvaert,Flagellation, Bologna,

Pinacoteca Nazionale,

1575-80

Ludovico Carracci,

Flagellation, Douai, Museo

della Certosa, 1584-90

57

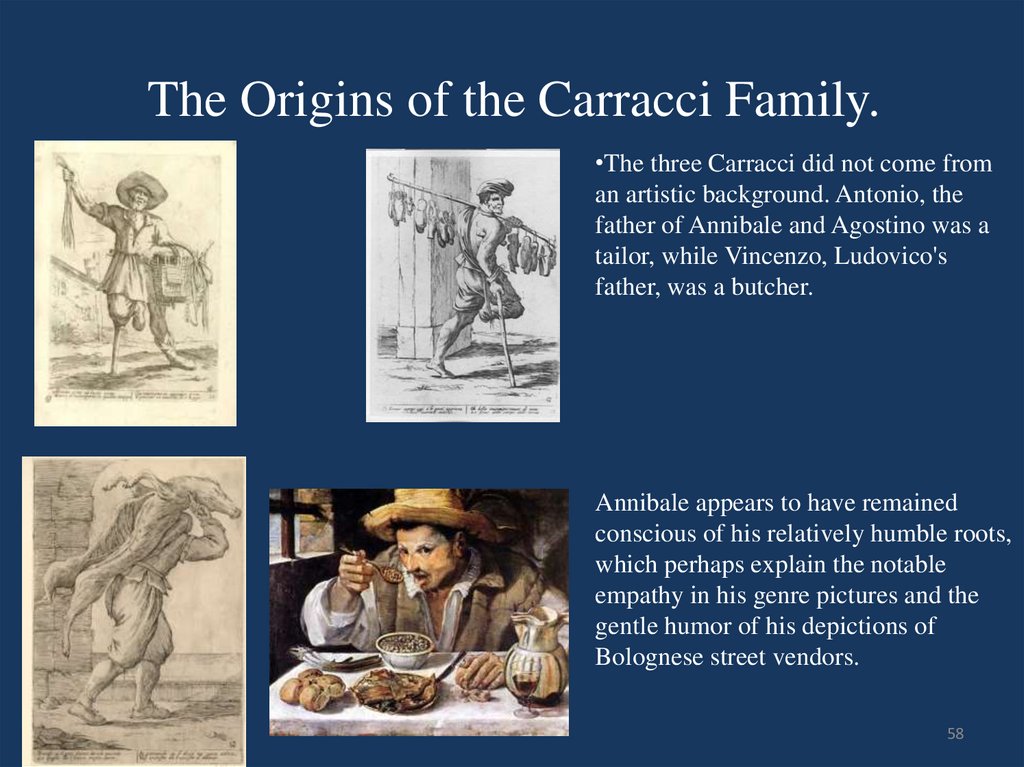

58. The Origins of the Carracci Family.

•The three Carracci did not come froman artistic background. Antonio, the

father of Annibale and Agostino was a

tailor, while Vincenzo, Ludovico's

father, was a butcher.

Annibale appears to have remained

conscious of his relatively humble roots,

which perhaps explain the notable

empathy in his genre pictures and the

gentle humor of his depictions of

Bolognese street vendors.

58

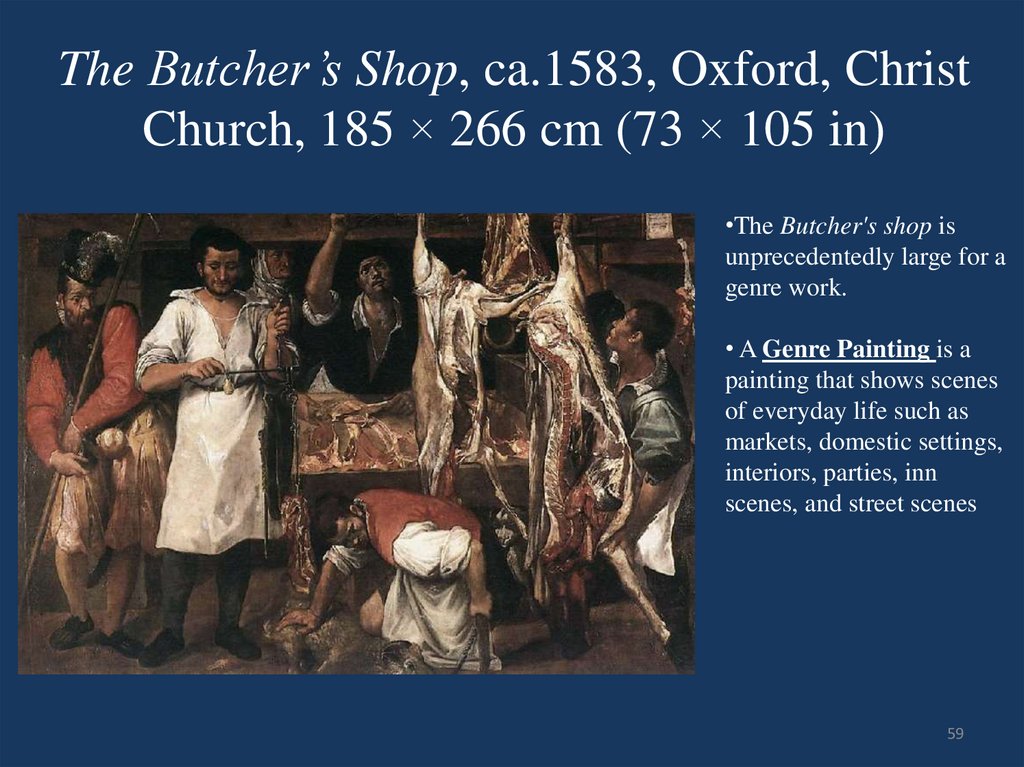

59. The Butcher’s Shop, ca.1583, Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

The Butcher’s Shop, ca.1583, Oxford, ChristChurch, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

•The Butcher's shop is

unprecedentedly large for a

genre work.

• A Genre Painting is a

painting that shows scenes

of everyday life such as

markets, domestic settings,

interiors, parties, inn

scenes, and street scenes

59

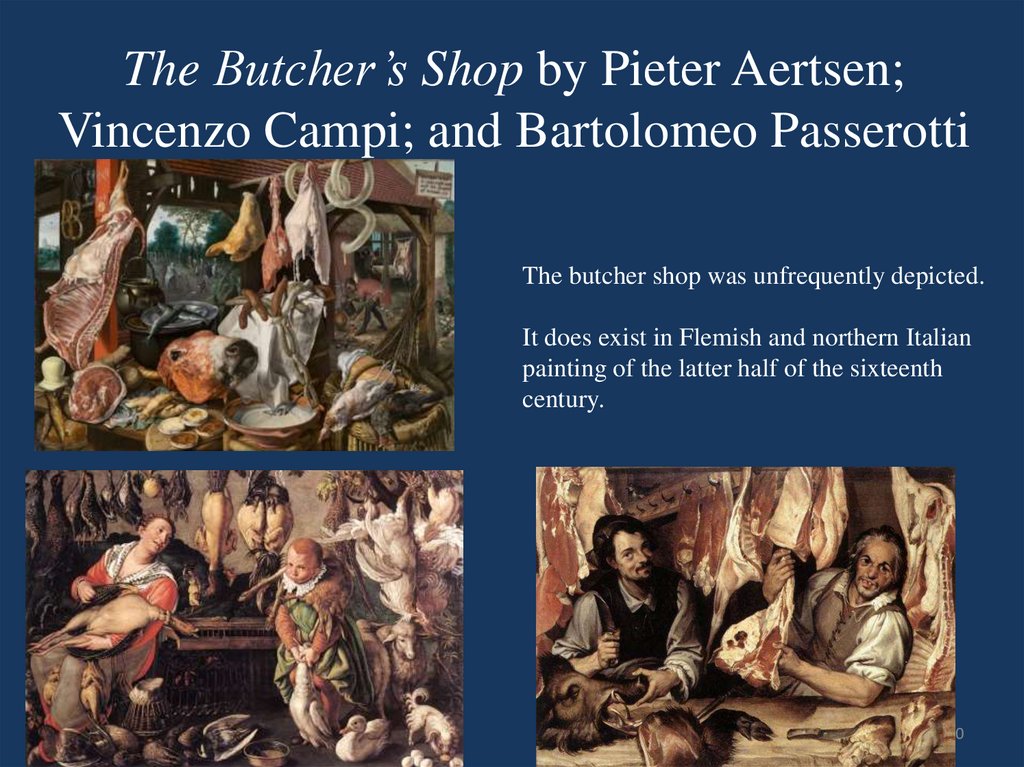

60. The Butcher’s Shop by Pieter Aertsen; Vincenzo Campi; and Bartolomeo Passerotti

The butcher shop was unfrequently depicted.It does exist in Flemish and northern Italian

painting of the latter half of the sixteenth

century.

60

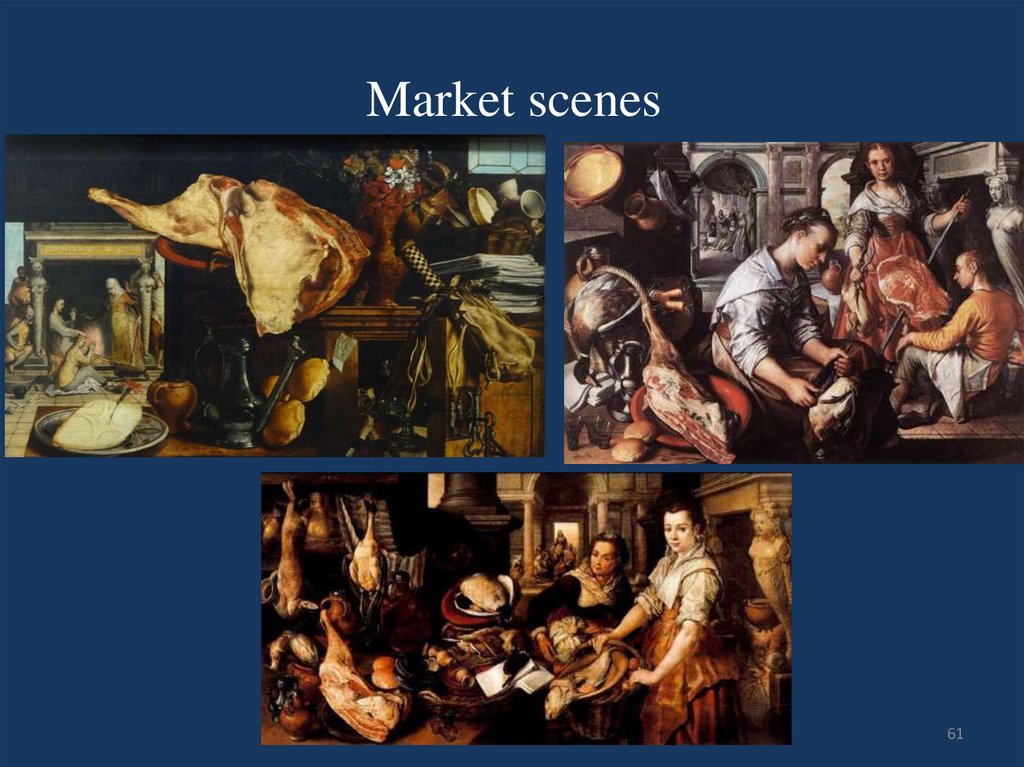

61. Market scenes

6162. Market scenes

But why would an artist depict meat incombination with a religious scene,

inverting the traditional hierarchies ?

This may be a comment on the arduous

nature of spirituality: those who truly seek

enlightenment must look hard, and turn

their attention away from the things of this

world.

62

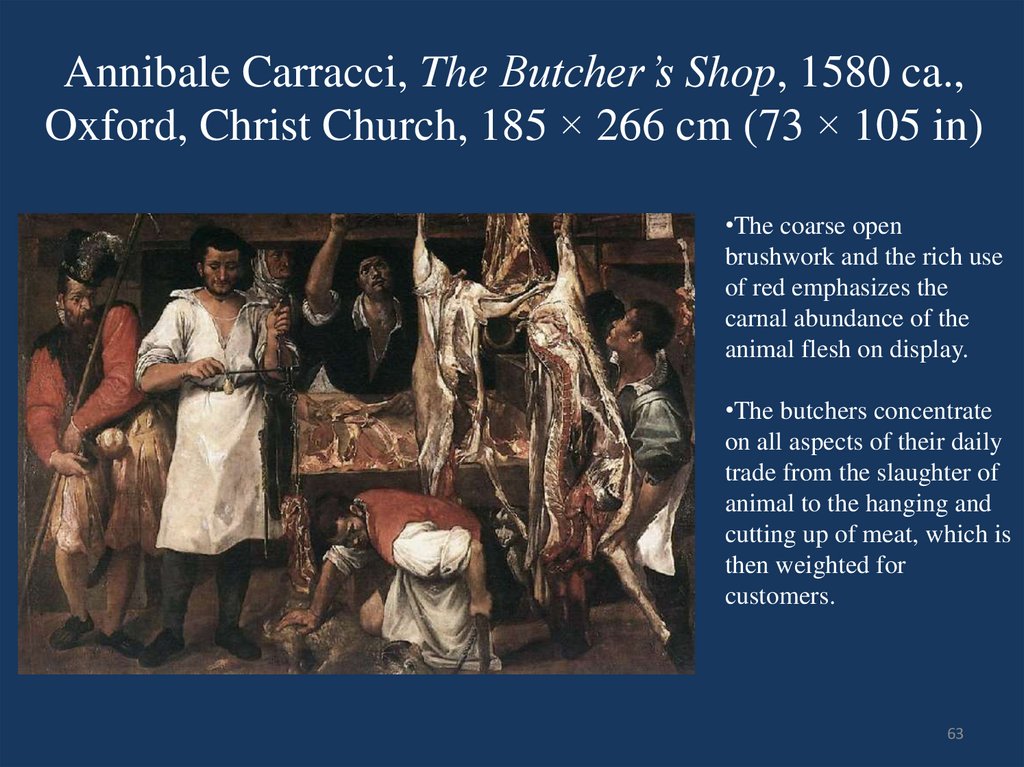

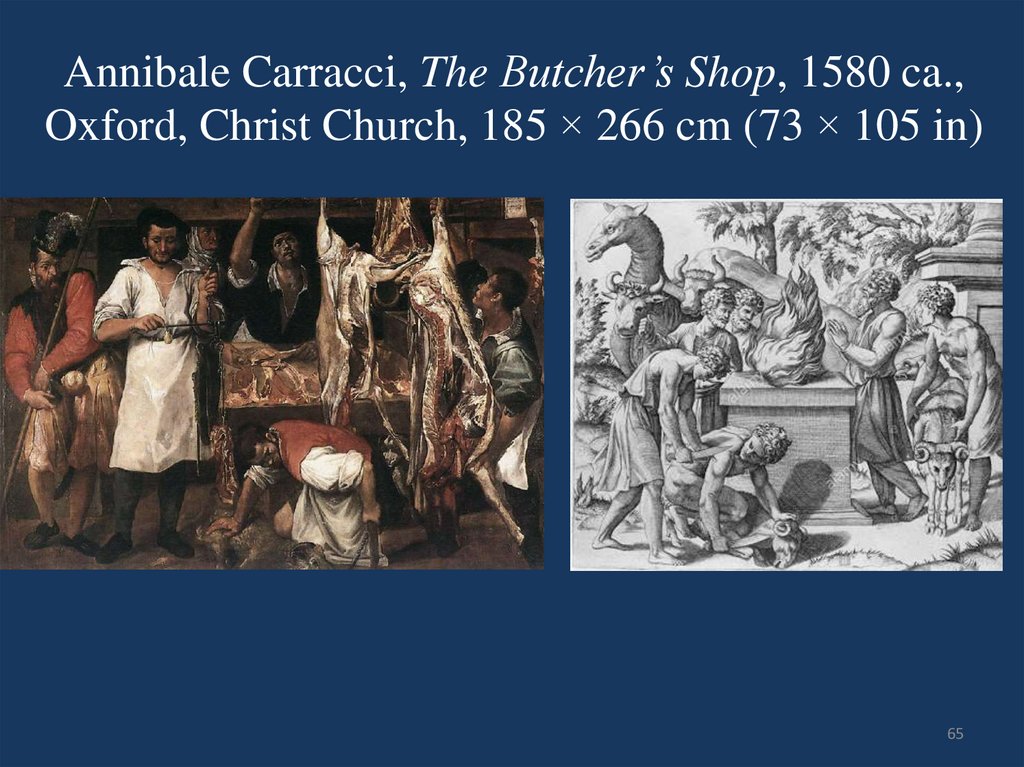

63. Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop, 1580 ca., Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop, 1580 ca.,Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

•The coarse open

brushwork and the rich use

of red emphasizes the

carnal abundance of the

animal flesh on display.

•The butchers concentrate

on all aspects of their daily

trade from the slaughter of

animal to the hanging and

cutting up of meat, which is

then weighted for

customers.

63

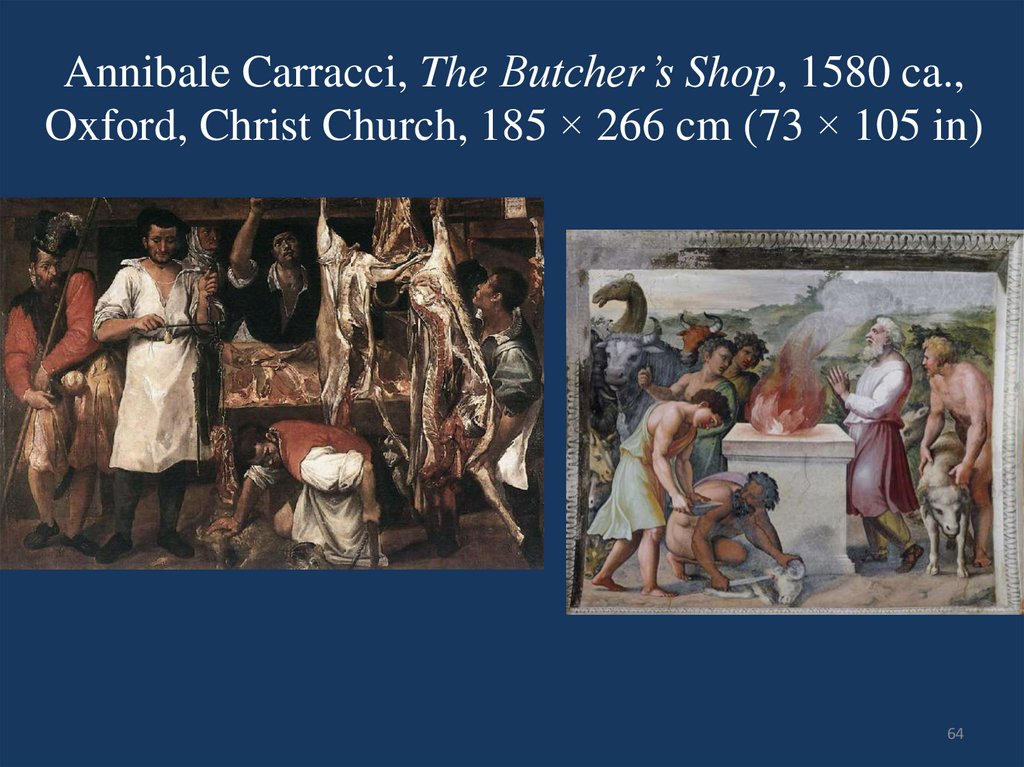

64. Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop, 1580 ca., Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop, 1580 ca.,Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

64

65. Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop, 1580 ca., Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

Annibale Carracci, The Butcher’s Shop, 1580 ca.,Oxford, Christ Church, 185 × 266 cm (73 × 105 in)

65

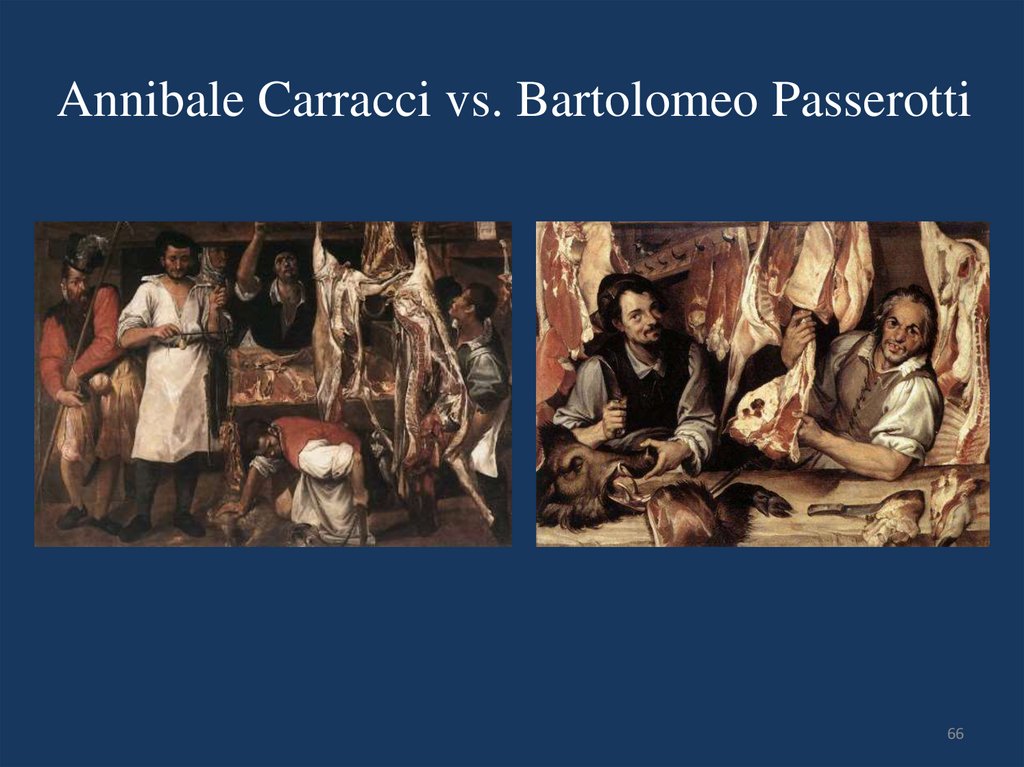

66. Annibale Carracci vs. Bartolomeo Passerotti

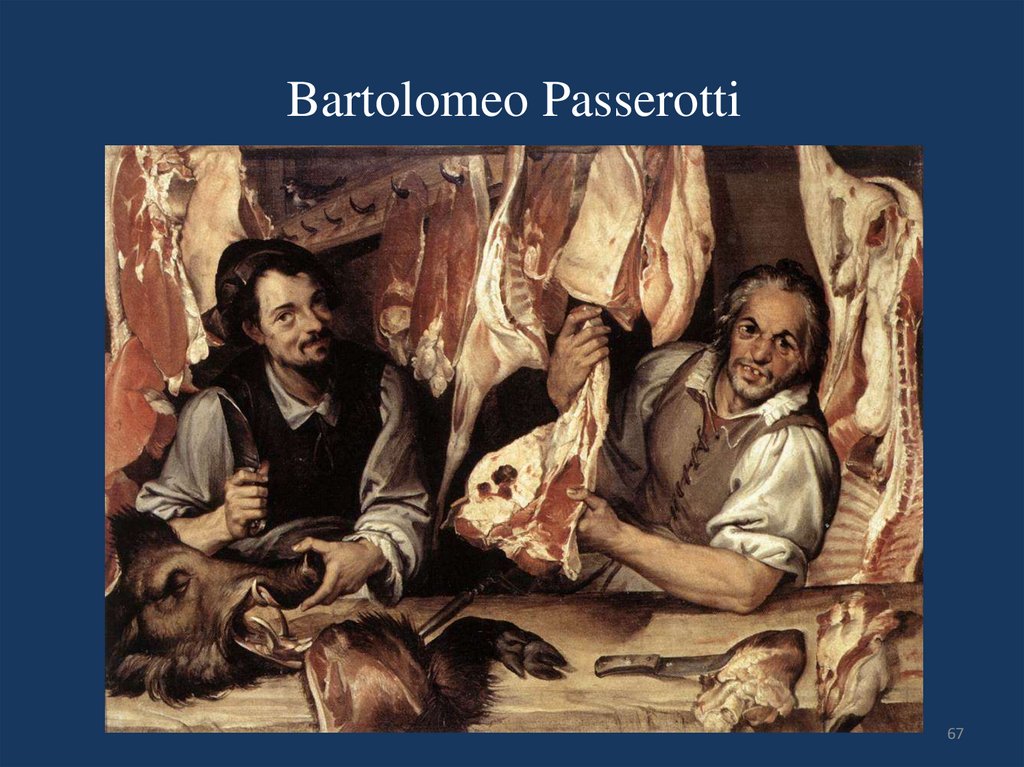

6667. Bartolomeo Passerotti

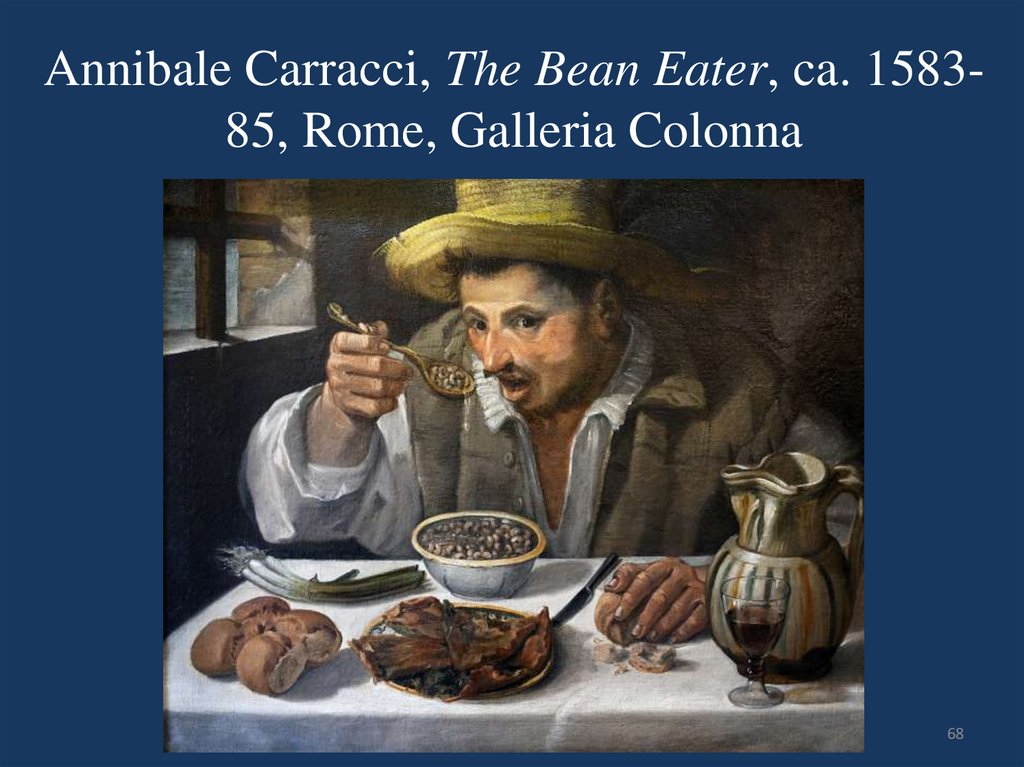

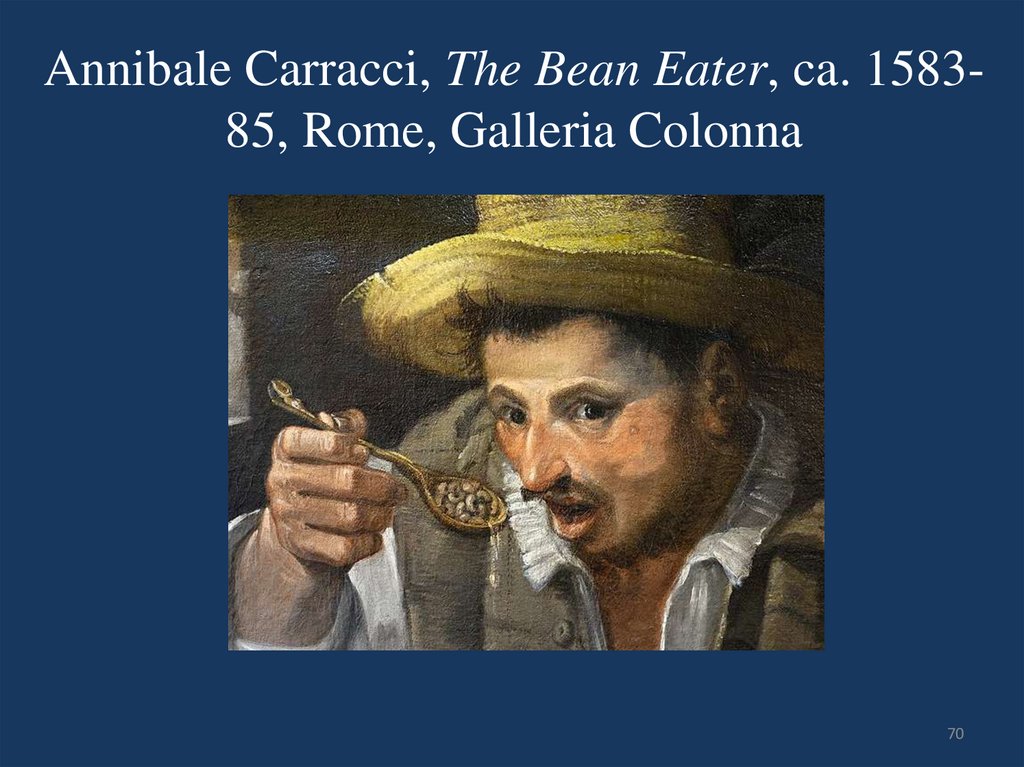

6768. Annibale Carracci, The Bean Eater, ca. 1583-85, Rome, Galleria Colonna

Annibale Carracci, The Bean Eater, ca. 158385, Rome, Galleria Colonna68

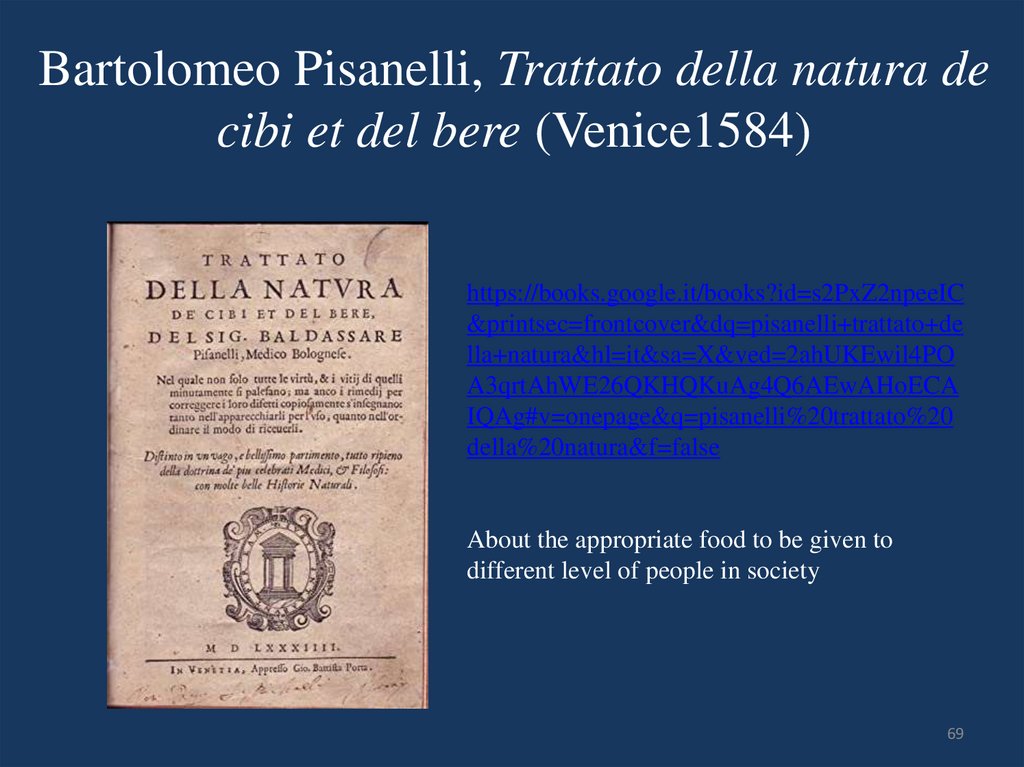

69. Bartolomeo Pisanelli, Trattato della natura de cibi et del bere (Venice1584)

https://books.google.it/books?id=s2PxZ2npeeIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=pisanelli+trattato+de

lla+natura&hl=it&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwil4PO

A3qrtAhWE26QKHQKuAg4Q6AEwAHoECA

IQAg#v=onepage&q=pisanelli%20trattato%20

della%20natura&f=false

About the appropriate food to be given to

different level of people in society

69

70. Annibale Carracci, The Bean Eater, ca. 1583-85, Rome, Galleria Colonna

Annibale Carracci, The Bean Eater, ca. 158385, Rome, Galleria Colonna70

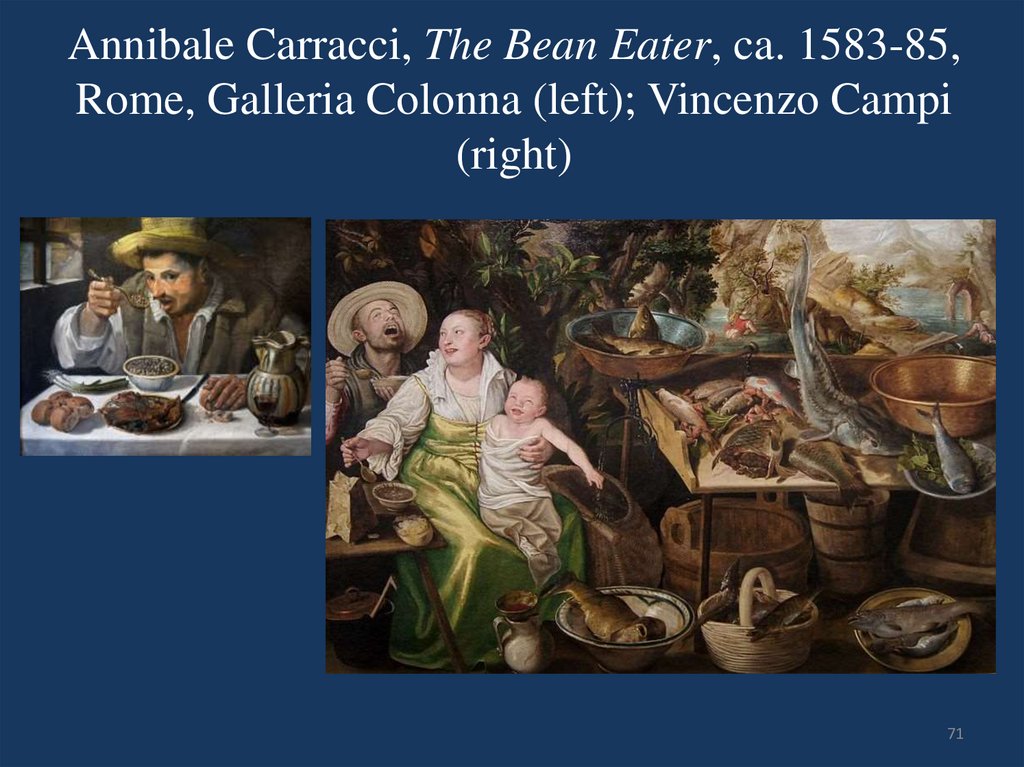

71. Annibale Carracci, The Bean Eater, ca. 1583-85, Rome, Galleria Colonna (left); Vincenzo Campi (right)

7172. Annibale Carracci vs. Vincenzo Campi

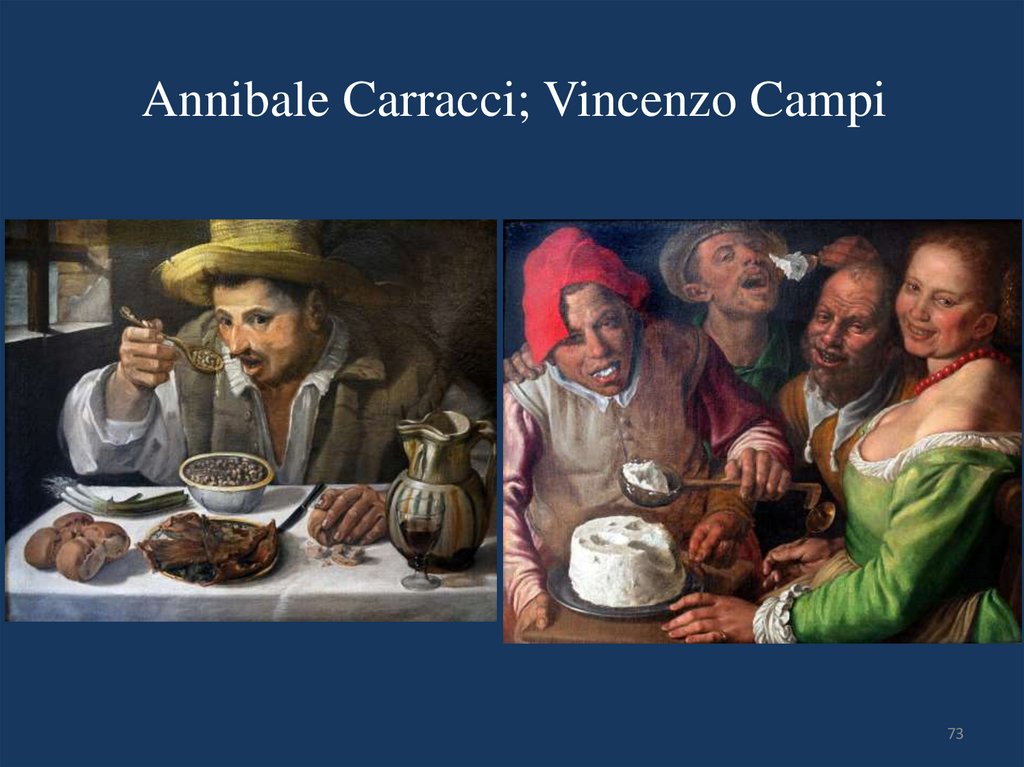

7273. Annibale Carracci; Vincenzo Campi

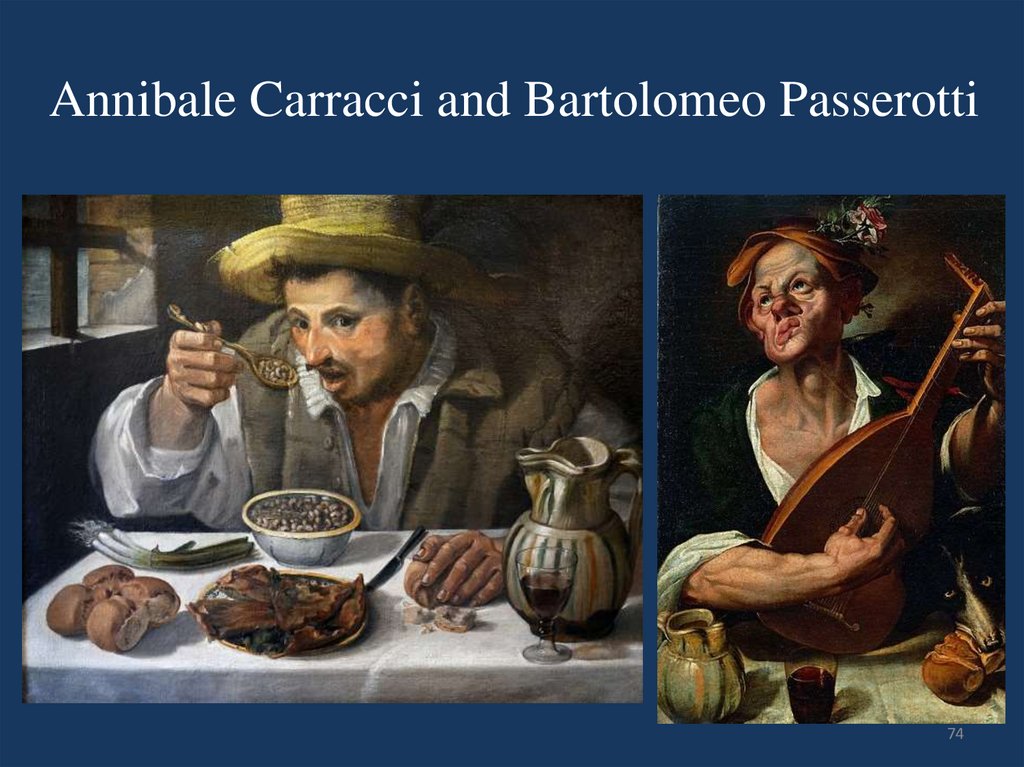

7374. Annibale Carracci and Bartolomeo Passerotti

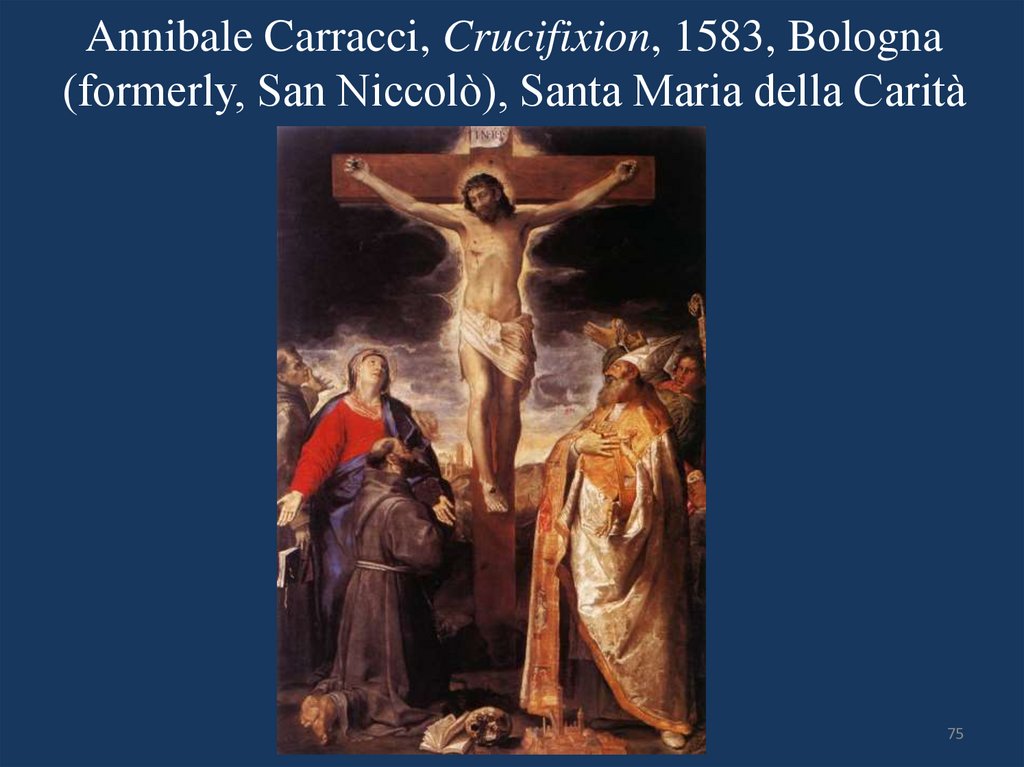

7475. Annibale Carracci, Crucifixion, 1583, Bologna (formerly, San Niccolò), Santa Maria della Carità

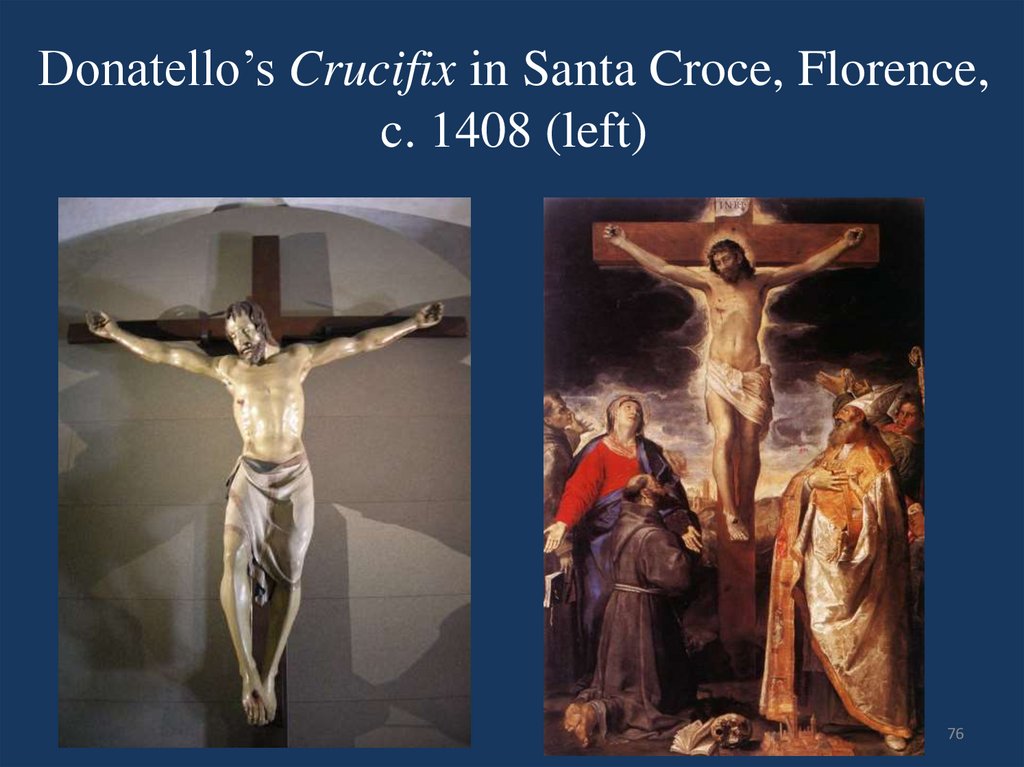

7576. Donatello’s Crucifix in Santa Croce, Florence, c. 1408 (left)

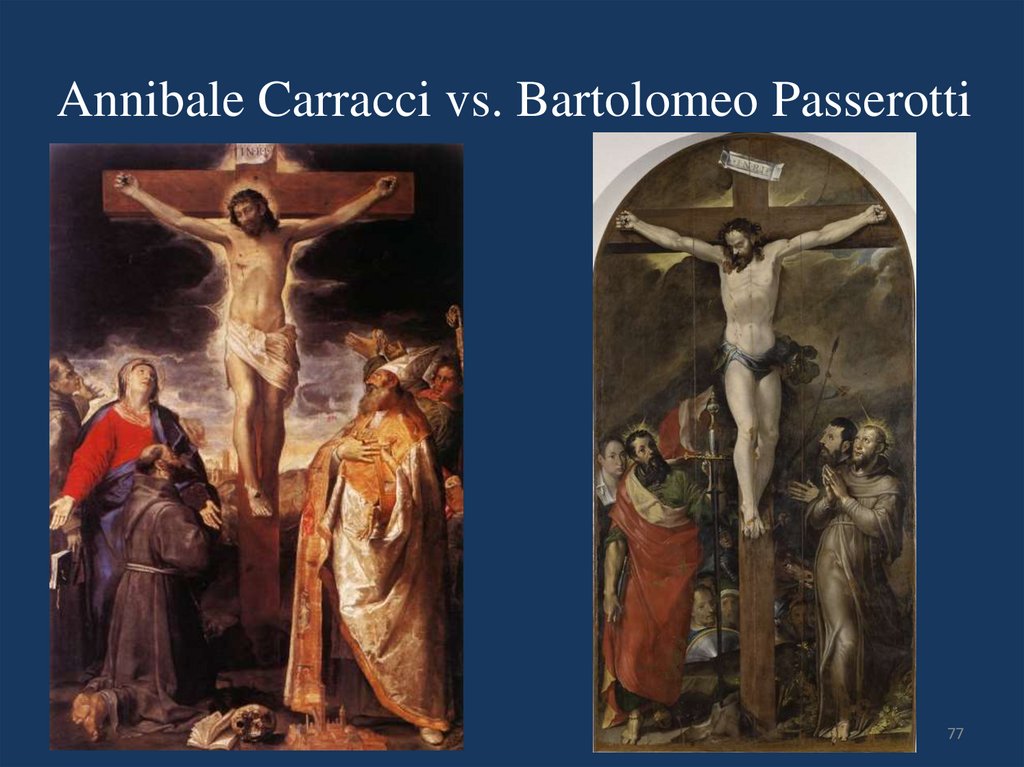

7677. Annibale Carracci vs. Bartolomeo Passerotti

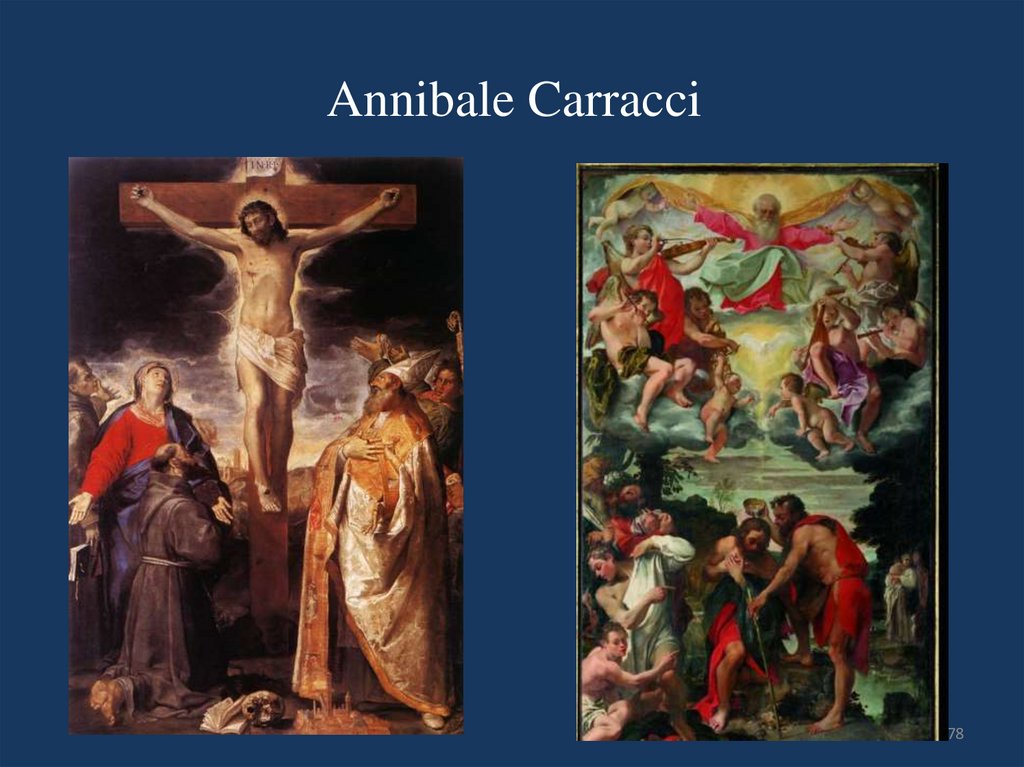

7778. Annibale Carracci

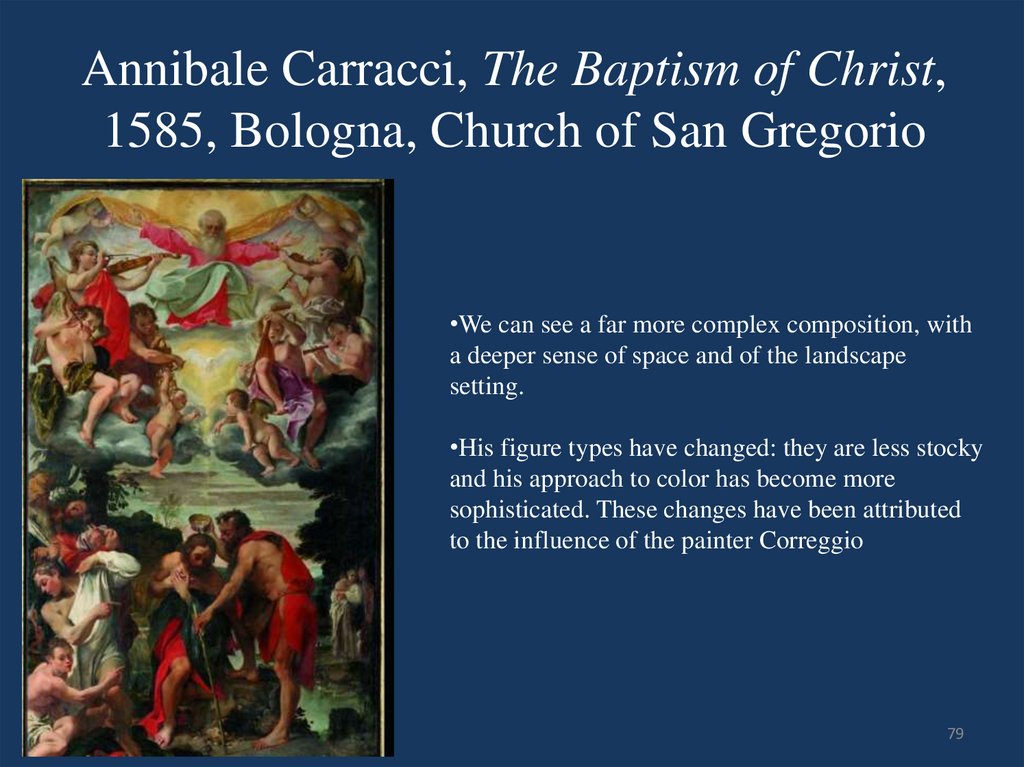

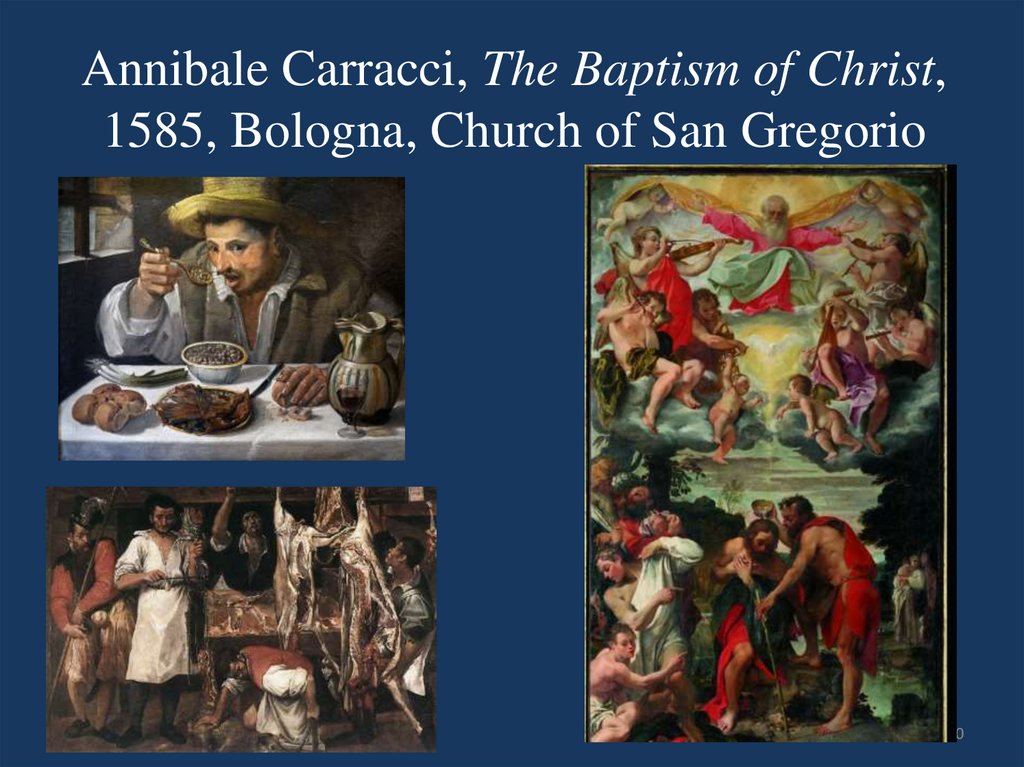

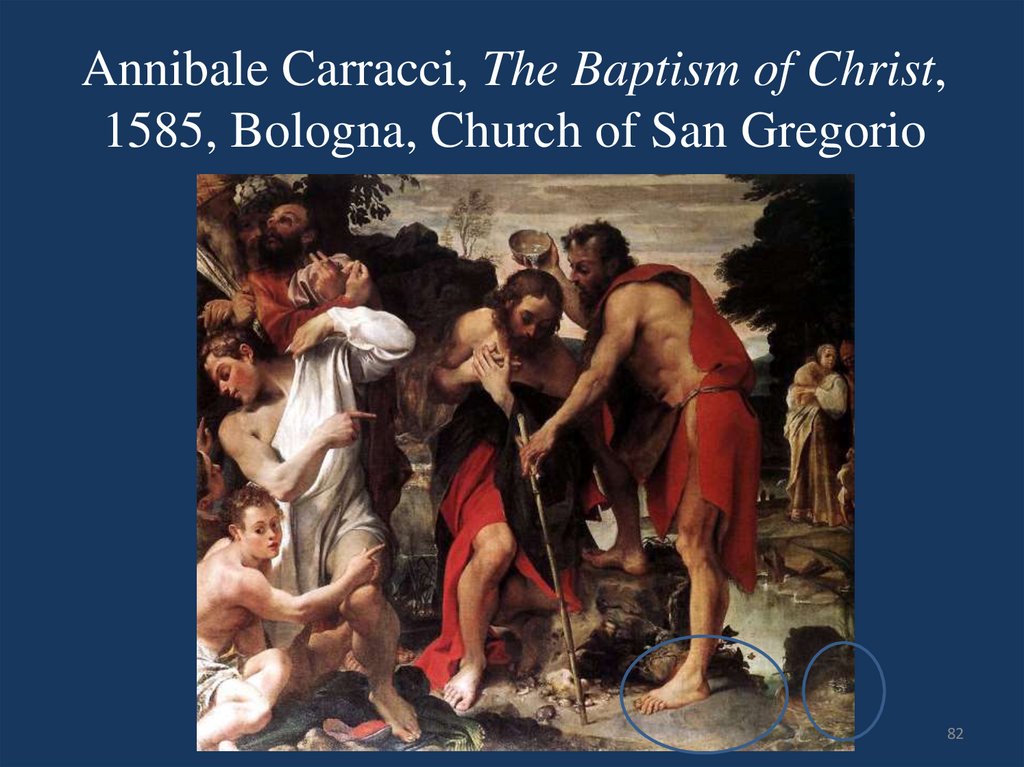

7879. Annibale Carracci, The Baptism of Christ, 1585, Bologna, Church of San Gregorio

•We can see a far more complex composition, witha deeper sense of space and of the landscape

setting.

•His figure types have changed: they are less stocky

and his approach to color has become more

sophisticated. These changes have been attributed

to the influence of the painter Correggio

79

80. Annibale Carracci, The Baptism of Christ, 1585, Bologna, Church of San Gregorio

8081. Annibale Carracci and the influence of Antonio Allegri il Correggio

8182. Annibale Carracci, The Baptism of Christ, 1585, Bologna, Church of San Gregorio

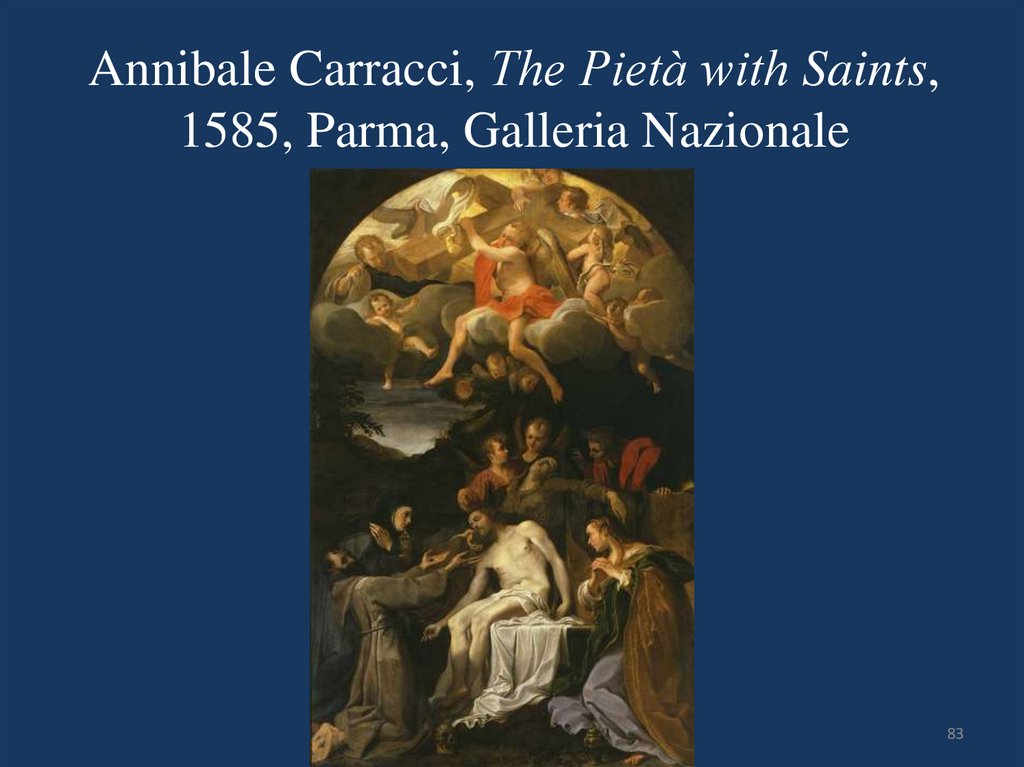

8283. Annibale Carracci, The Pietà with Saints, 1585, Parma, Galleria Nazionale

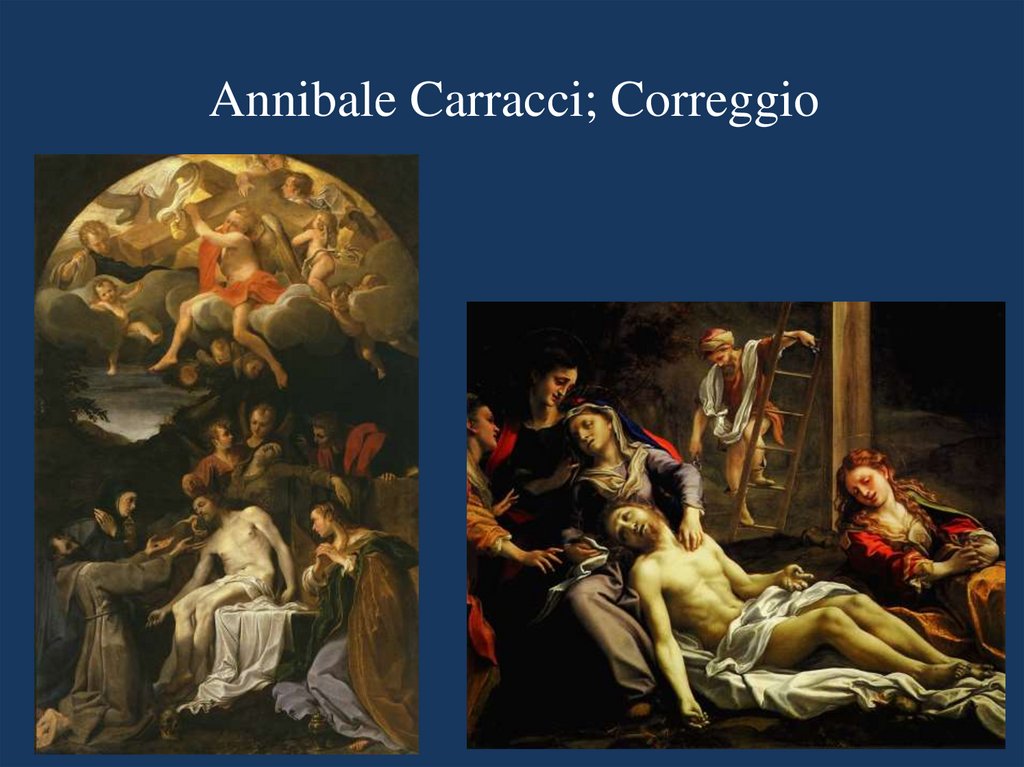

8384. Annibale Carracci; Correggio

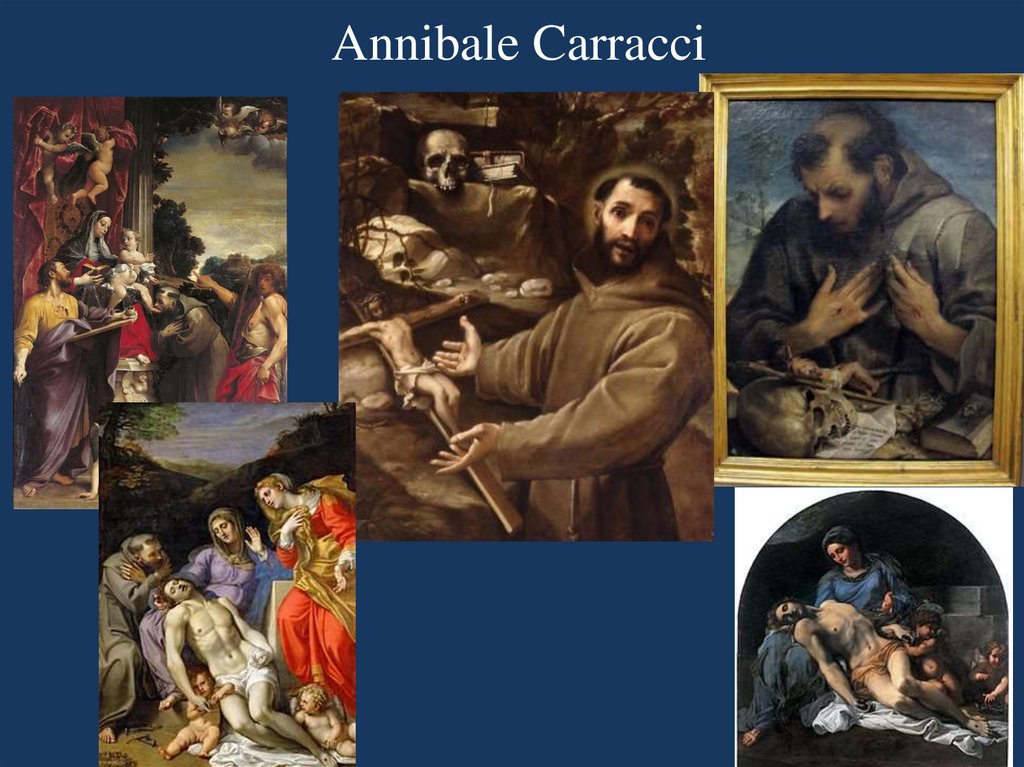

8485. Annibale Carracci

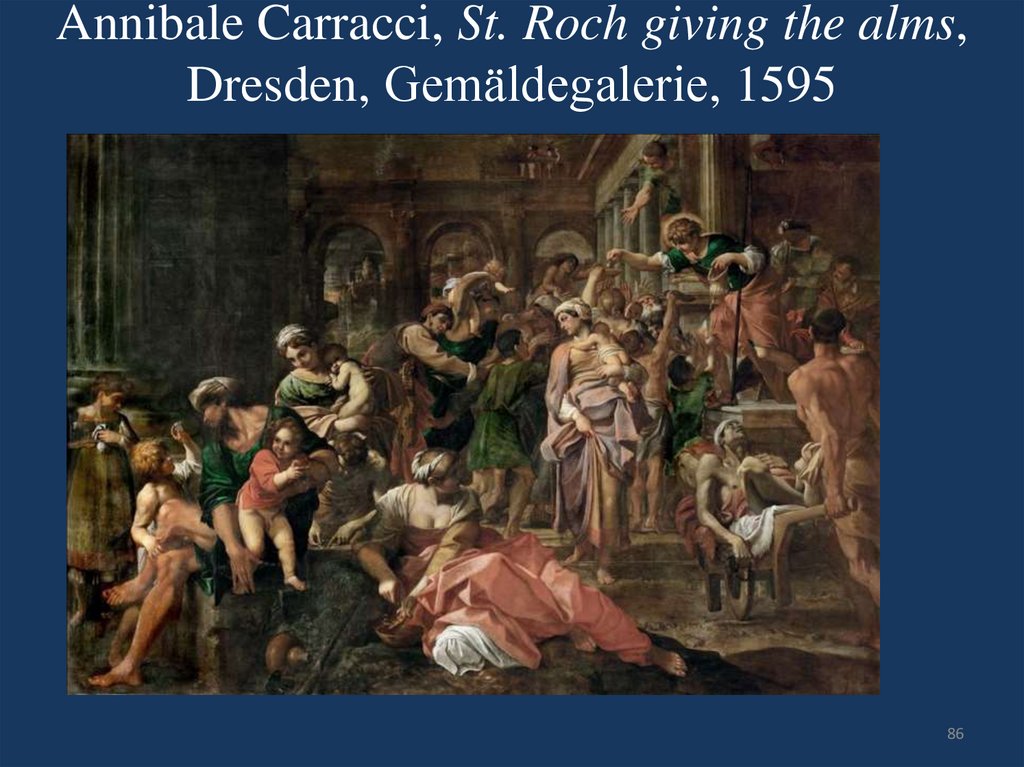

8586. Annibale Carracci, St. Roch giving the alms, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie, 1595

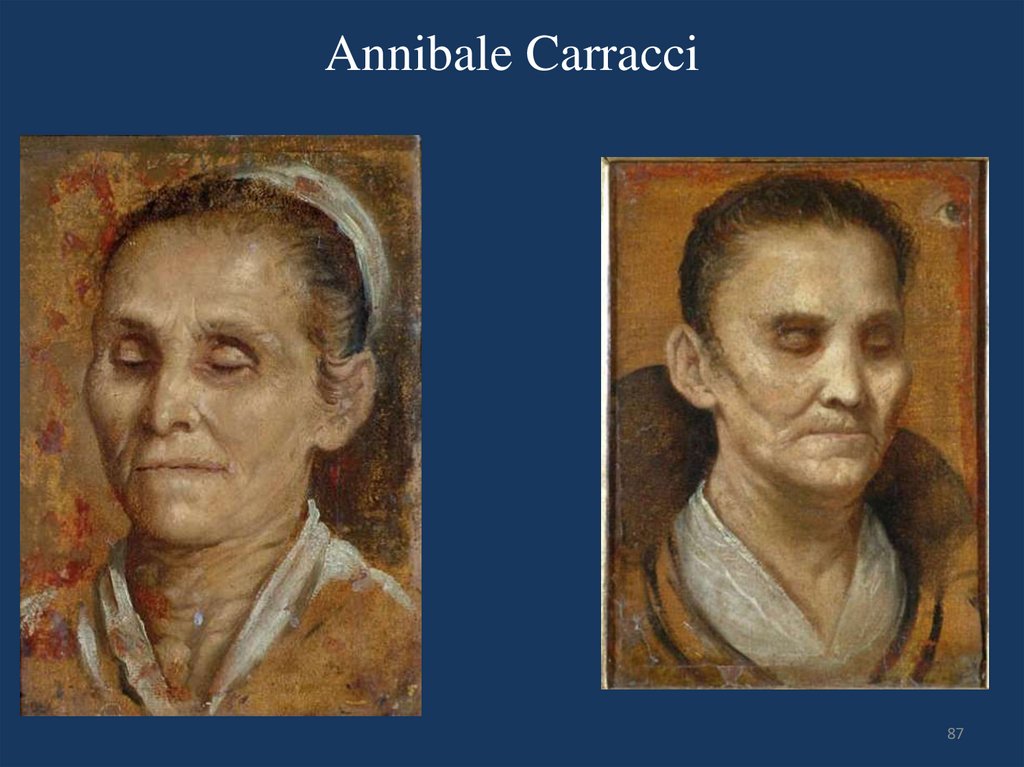

8687. Annibale Carracci

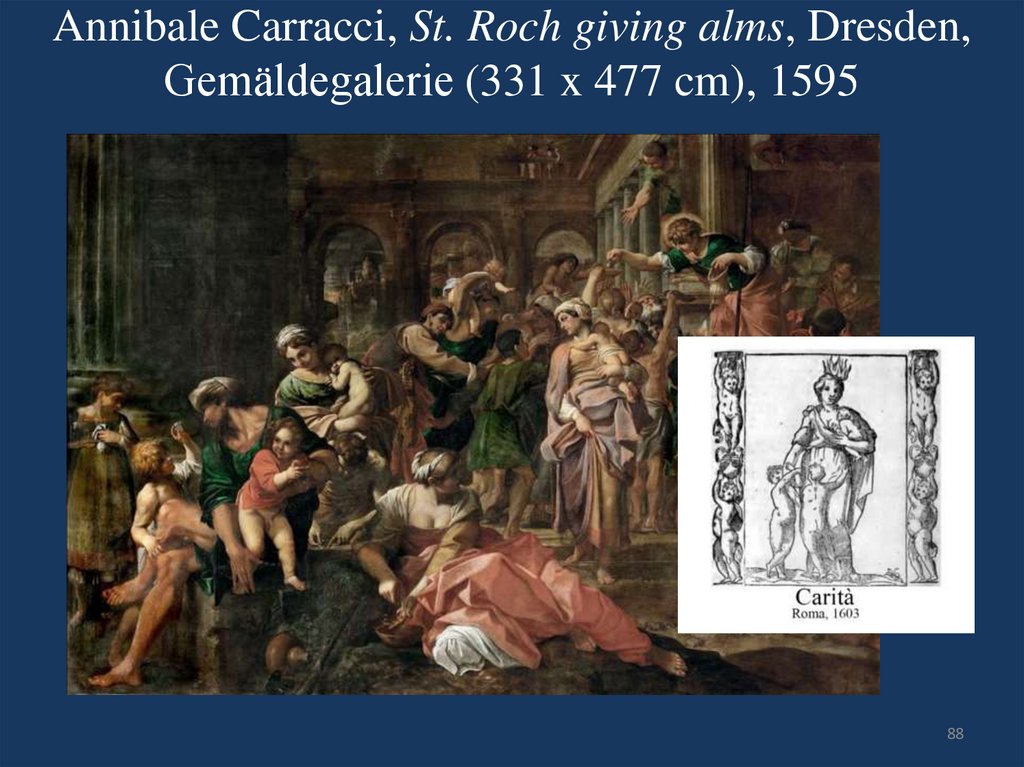

8788. Annibale Carracci, St. Roch giving alms, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie (331 x 477 cm), 1595

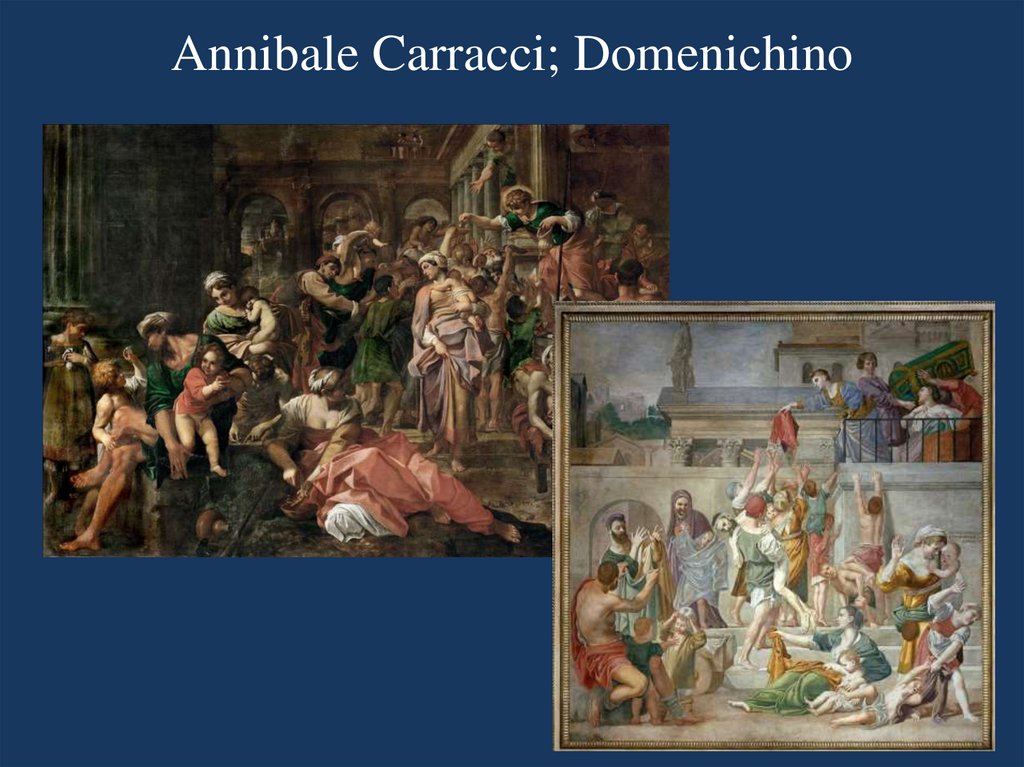

8889. Annibale Carracci; Domenichino

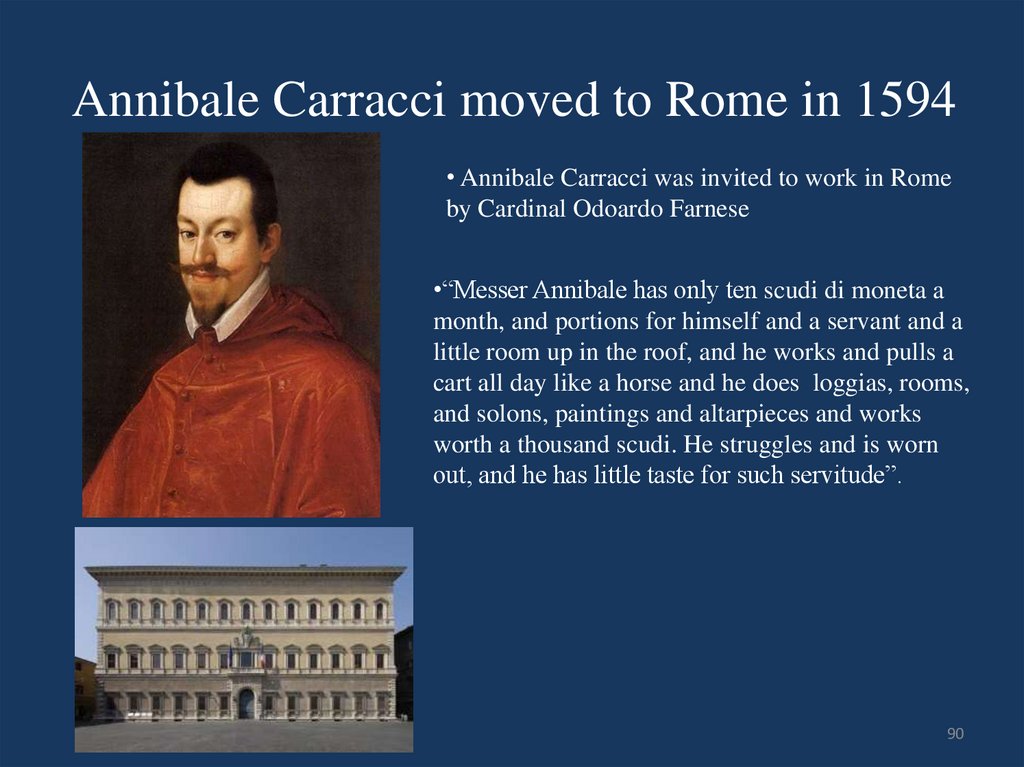

8990. Annibale Carracci moved to Rome in 1594

• Annibale Carracci was invited to work in Romeby Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

•“Messer Annibale has only ten scudi di moneta a

month, and portions for himself and a servant and a

little room up in the roof, and he works and pulls a

cart all day like a horse and he does loggias, rooms,

and solons, paintings and altarpieces and works

worth a thousand scudi. He struggles and is worn

out, and he has little taste for such servitude”.

90

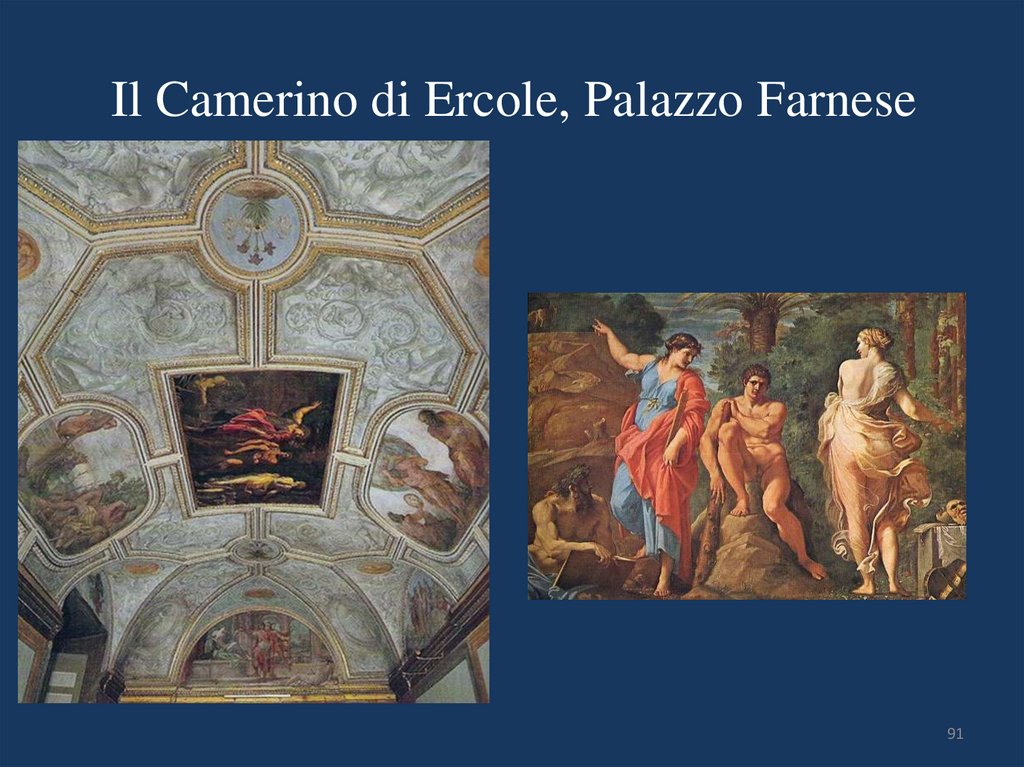

91. Il Camerino di Ercole, Palazzo Farnese

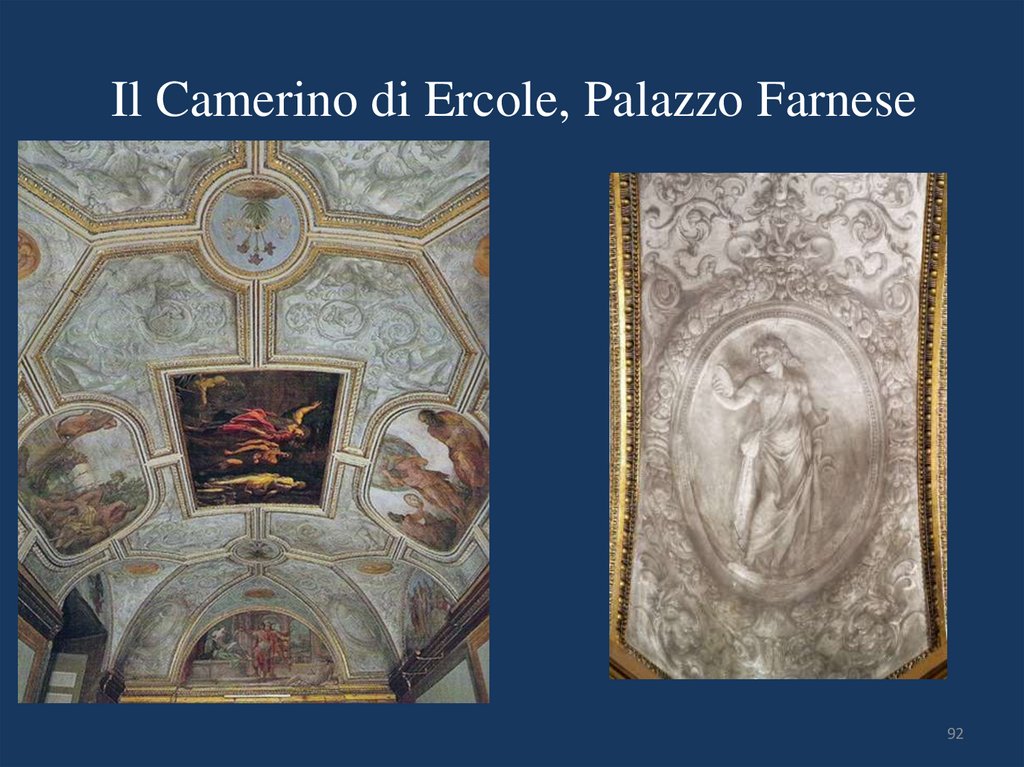

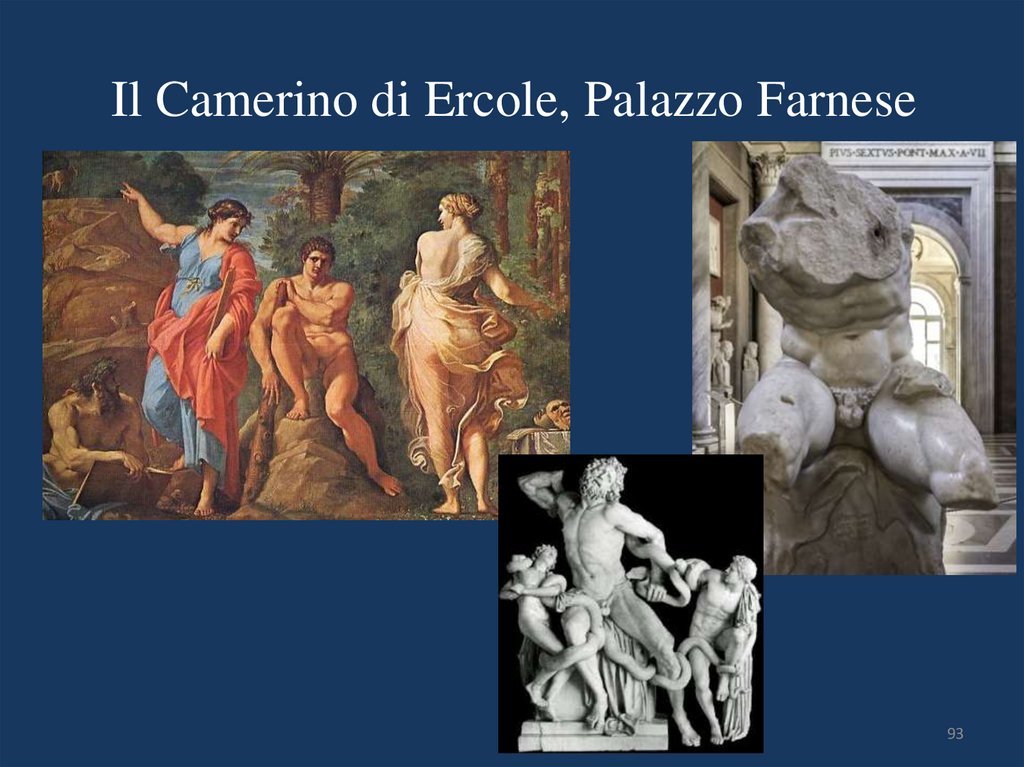

9192. Il Camerino di Ercole, Palazzo Farnese

9293. Il Camerino di Ercole, Palazzo Farnese

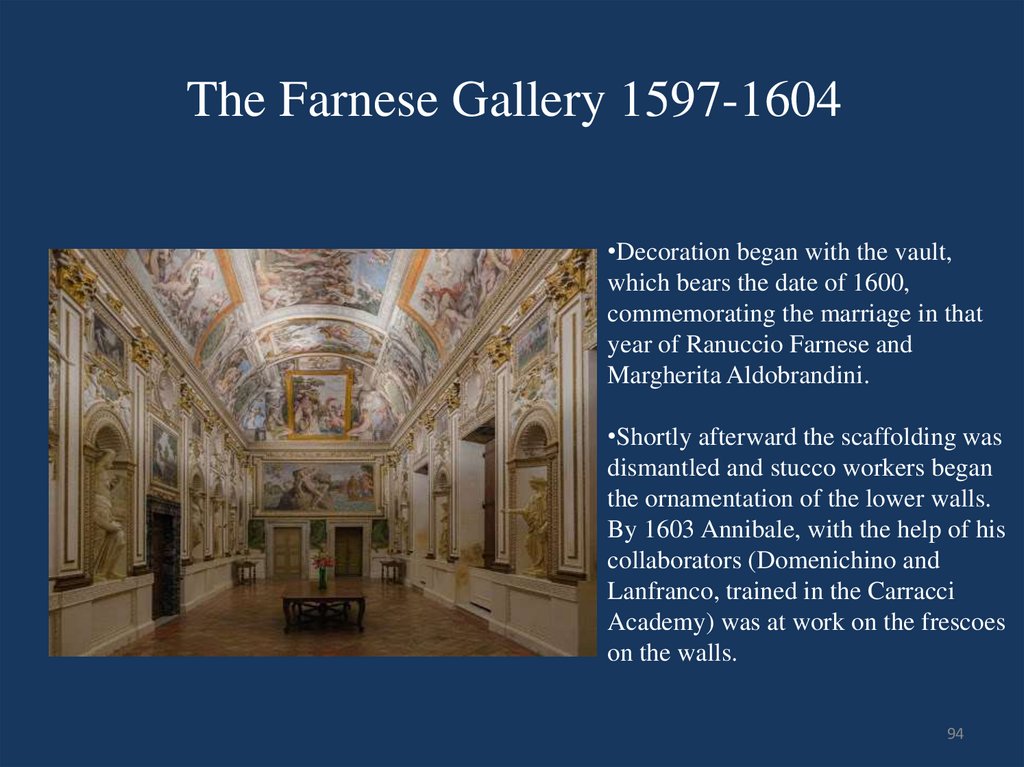

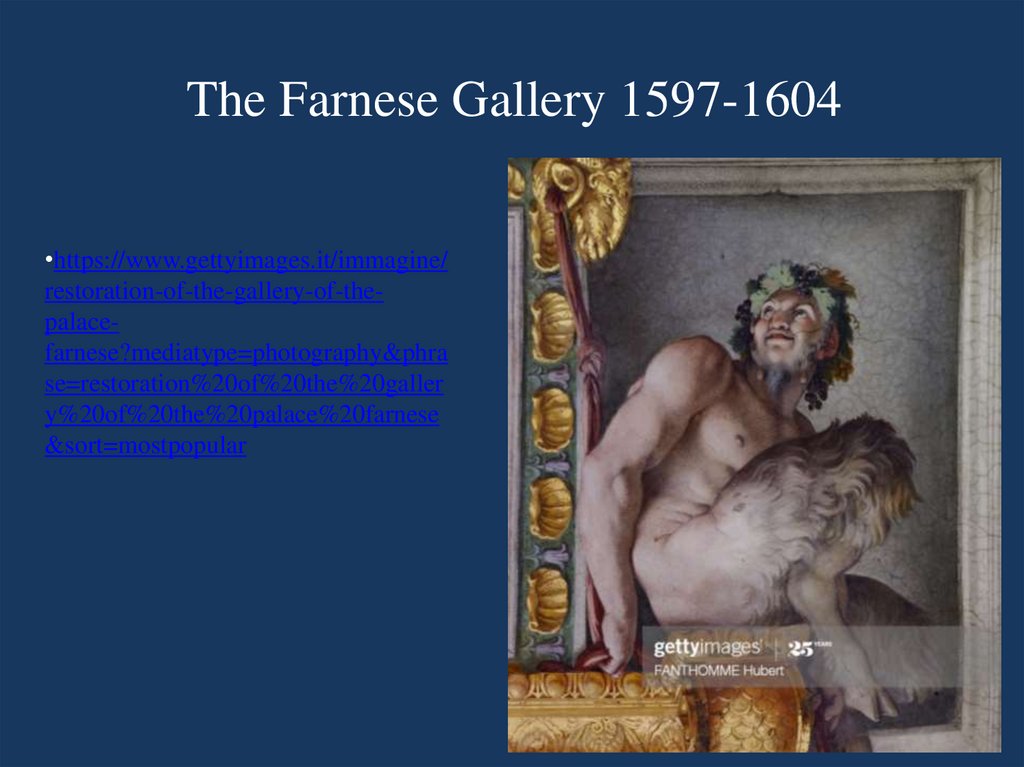

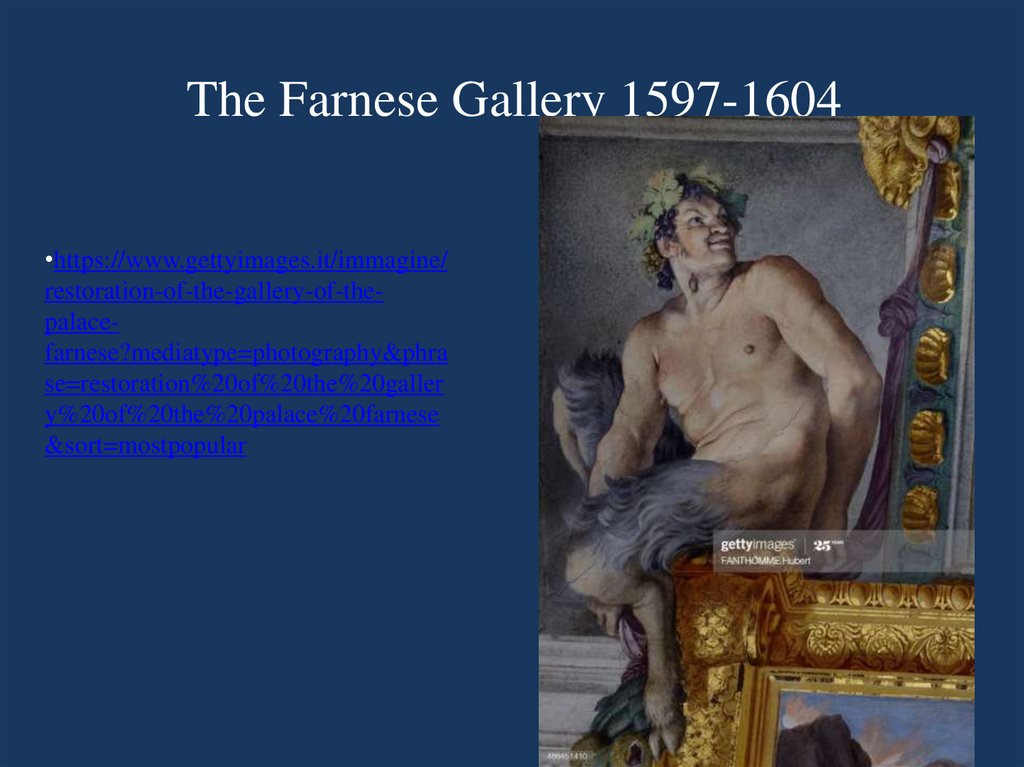

9394. The Farnese Gallery 1597-1604

•Decoration began with the vault,which bears the date of 1600,

commemorating the marriage in that

year of Ranuccio Farnese and

Margherita Aldobrandini.

•Shortly afterward the scaffolding was

dismantled and stucco workers began

the ornamentation of the lower walls.

By 1603 Annibale, with the help of his

collaborators (Domenichino and

Lanfranco, trained in the Carracci

Academy) was at work on the frescoes

on the walls.

94

95. The Farnese Gallery 1597-1604

•https://www.gettyimages.it/immagine/restoration-of-the-gallery-of-thepalacefarnese?mediatype=photography&phra

se=restoration%20of%20the%20galler

y%20of%20the%20palace%20farnese

&sort=mostpopular

95

96. The Farnese Gallery 1597-1604

•https://www.gettyimages.it/immagine/restoration-of-the-gallery-of-thepalacefarnese?mediatype=photography&phra

se=restoration%20of%20the%20galler

y%20of%20the%20palace%20farnese

&sort=mostpopular

96

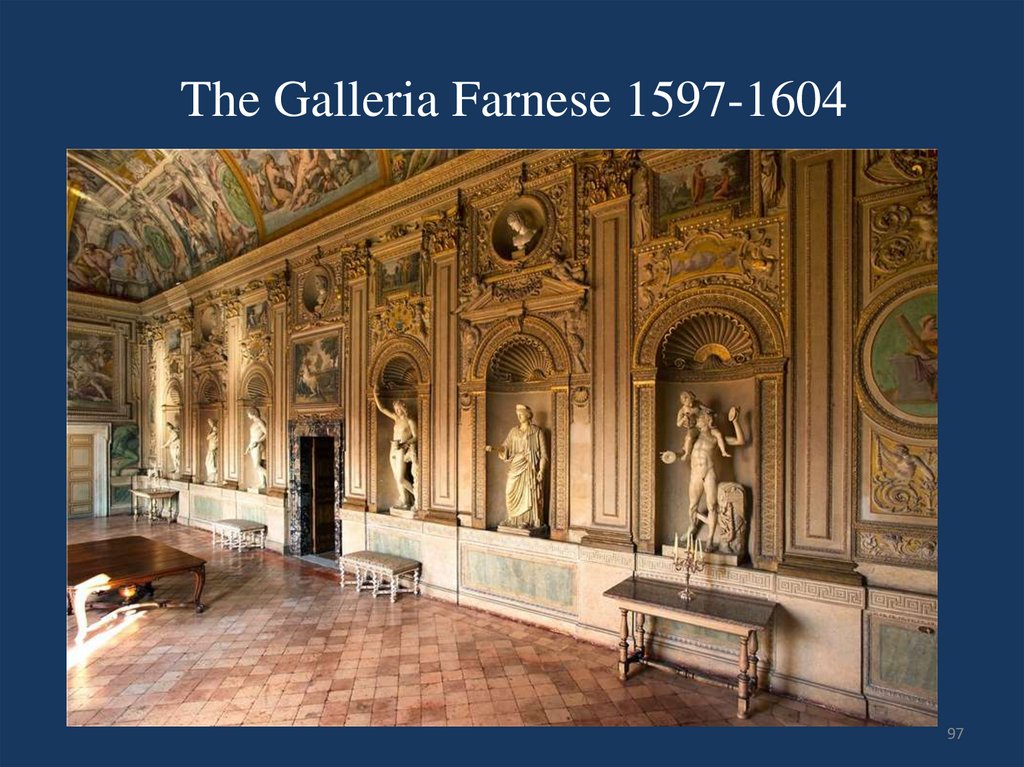

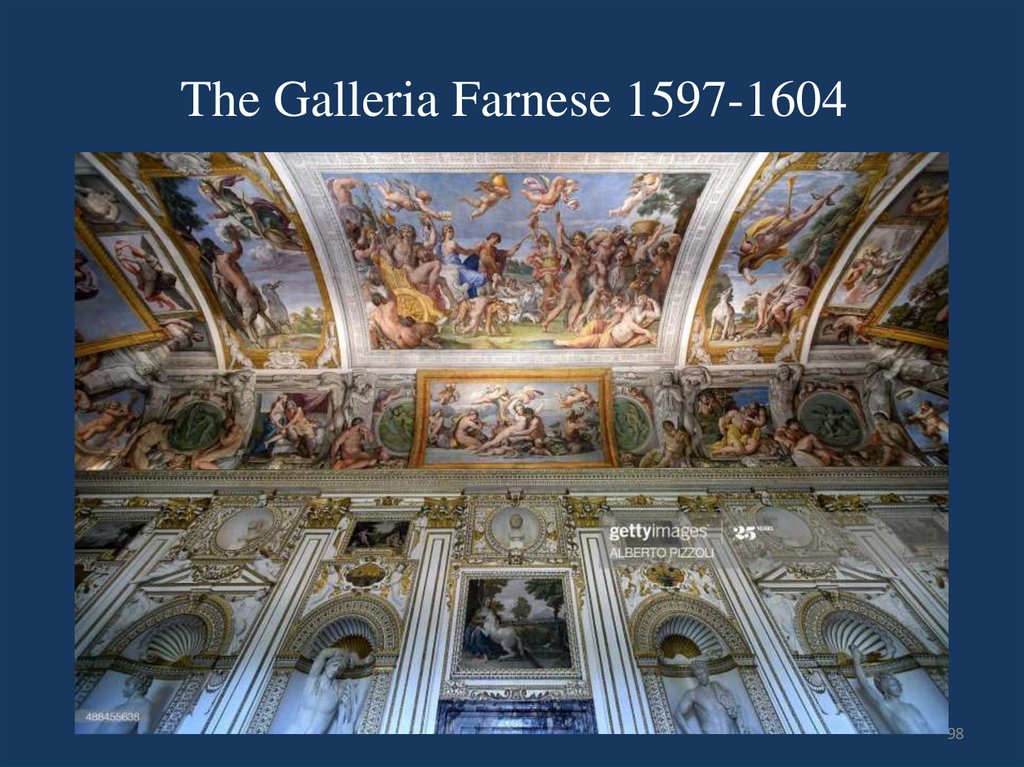

97. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

9798. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

9899. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

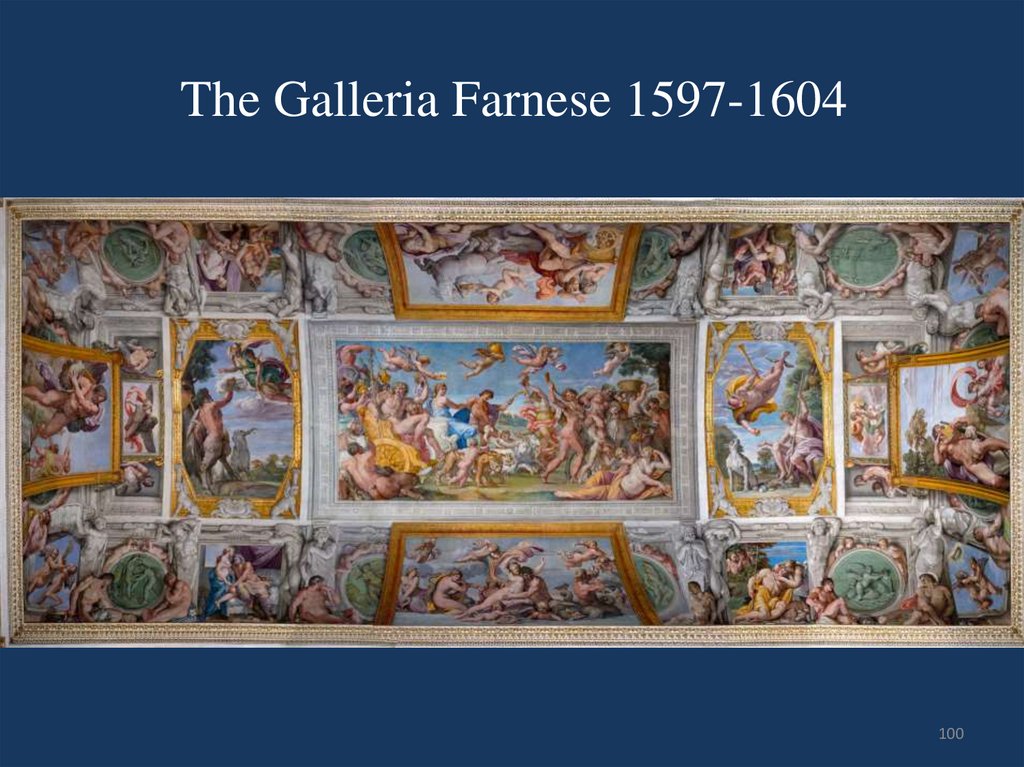

99100. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

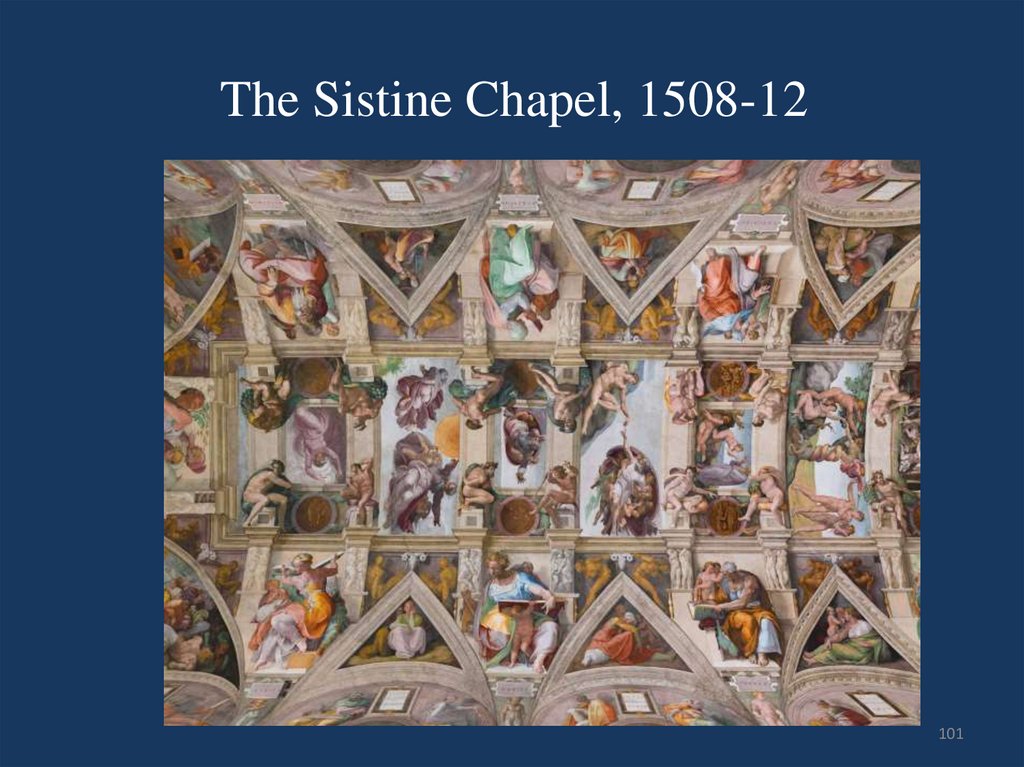

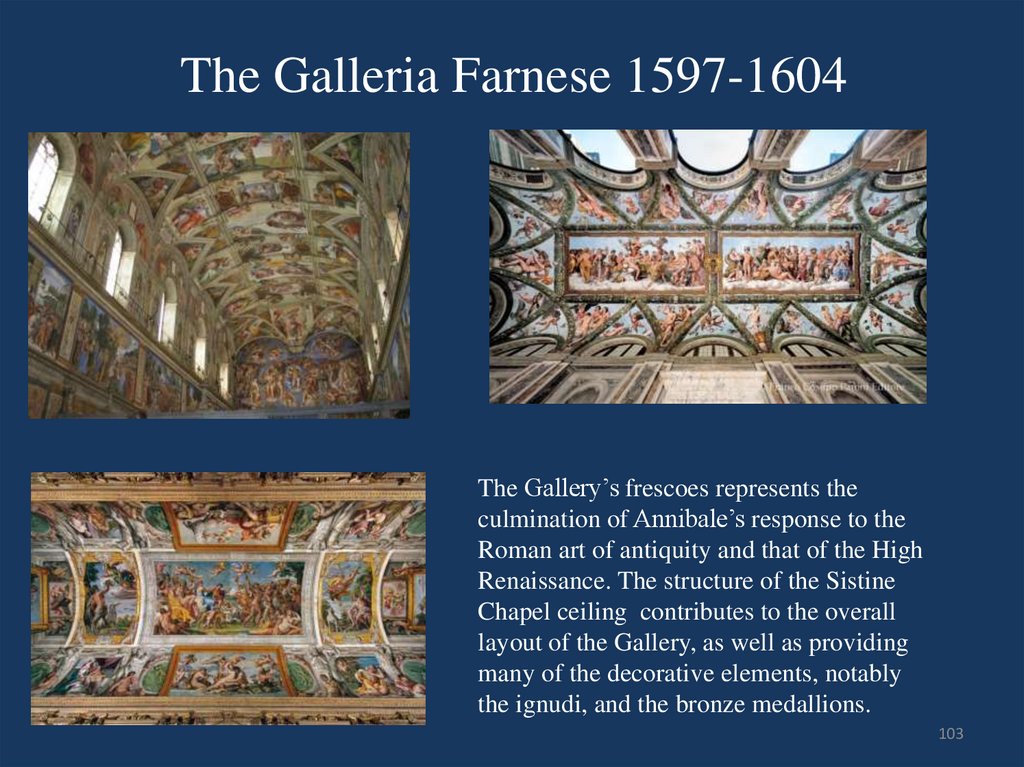

100101. The Sistine Chapel, 1508-12

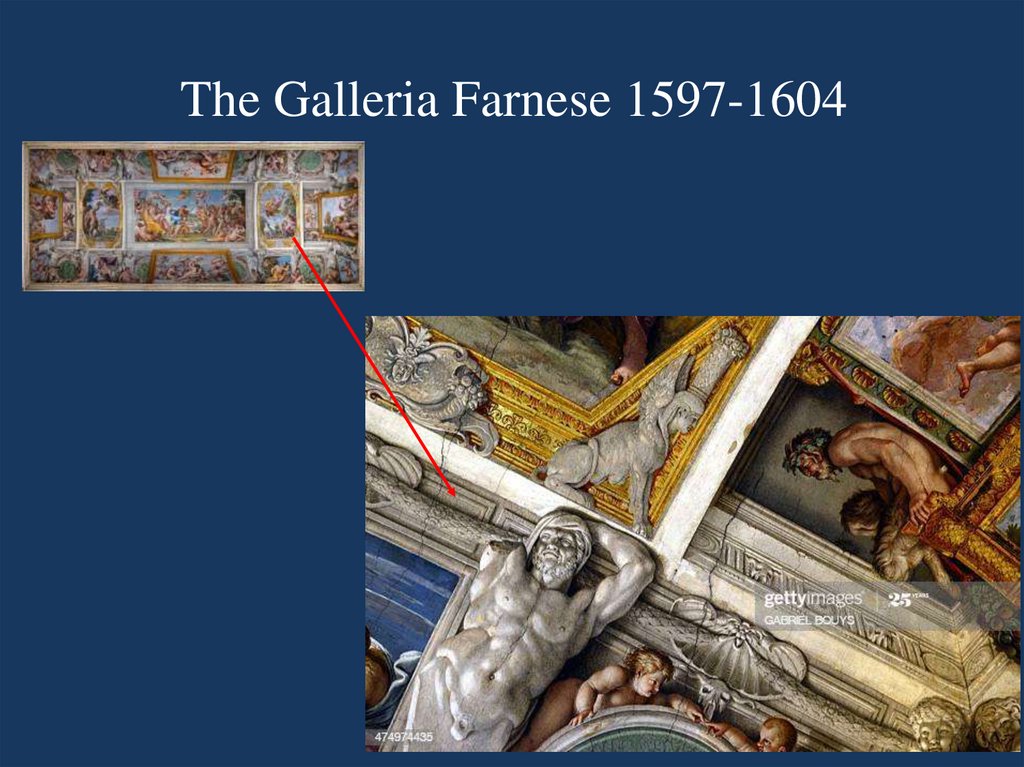

101102. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

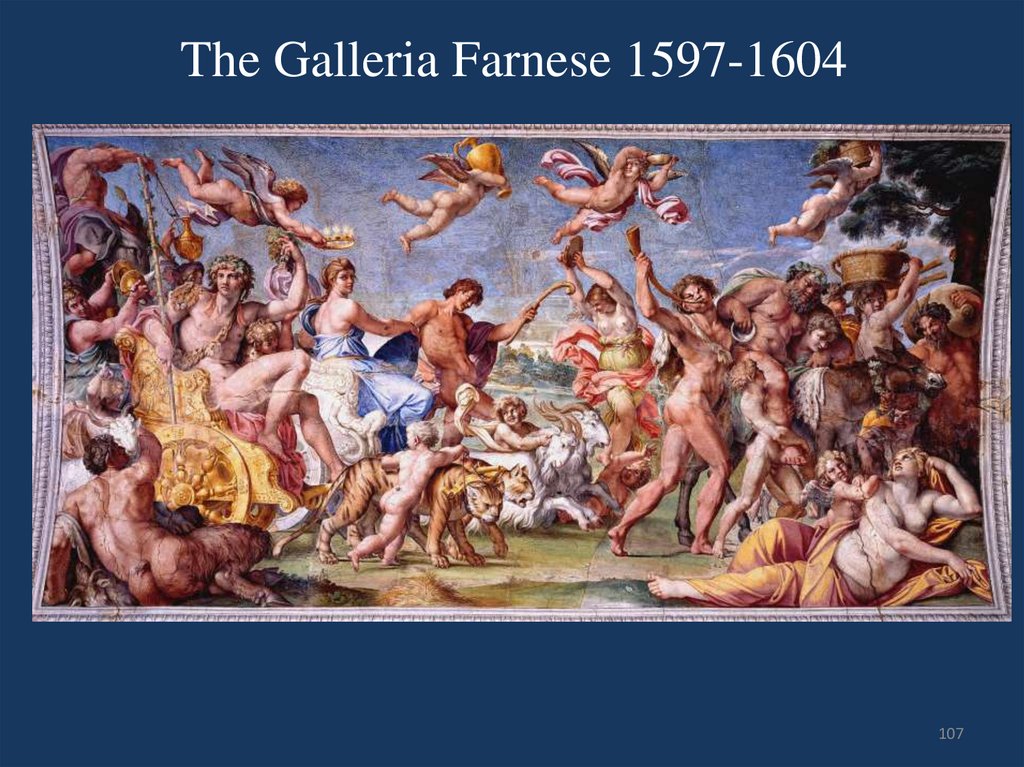

102103. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

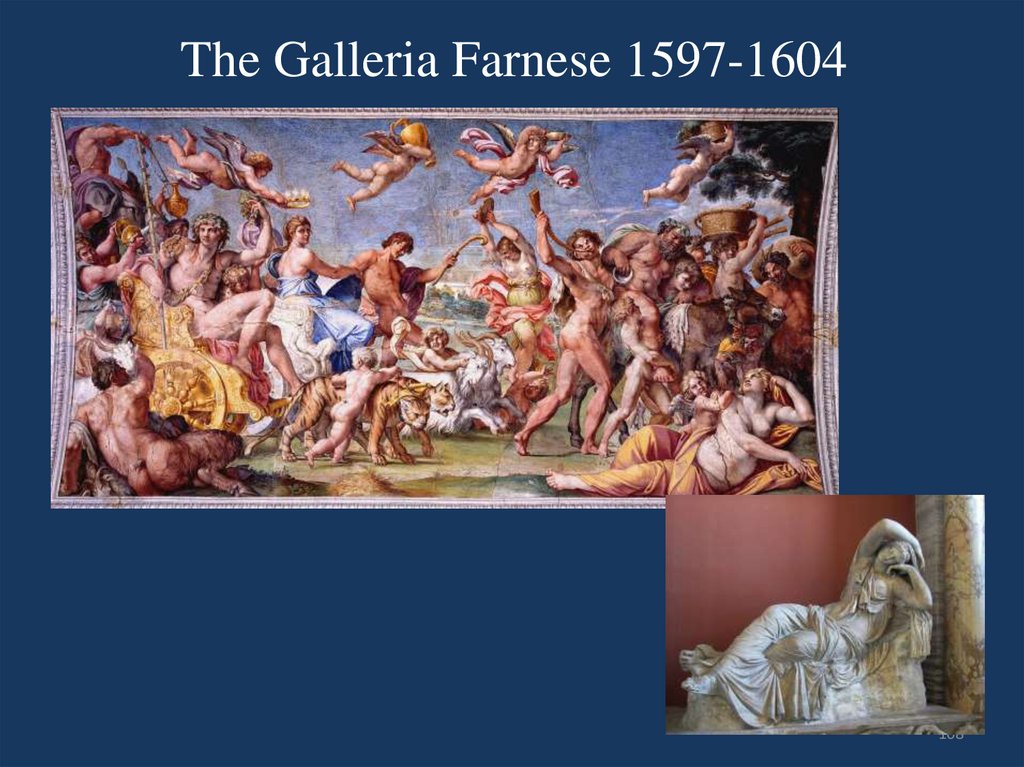

The Gallery’s frescoes represents theculmination of Annibale’s response to the

Roman art of antiquity and that of the High

Renaissance. The structure of the Sistine

Chapel ceiling contributes to the overall

layout of the Gallery, as well as providing

many of the decorative elements, notably

the ignudi, and the bronze medallions.

103

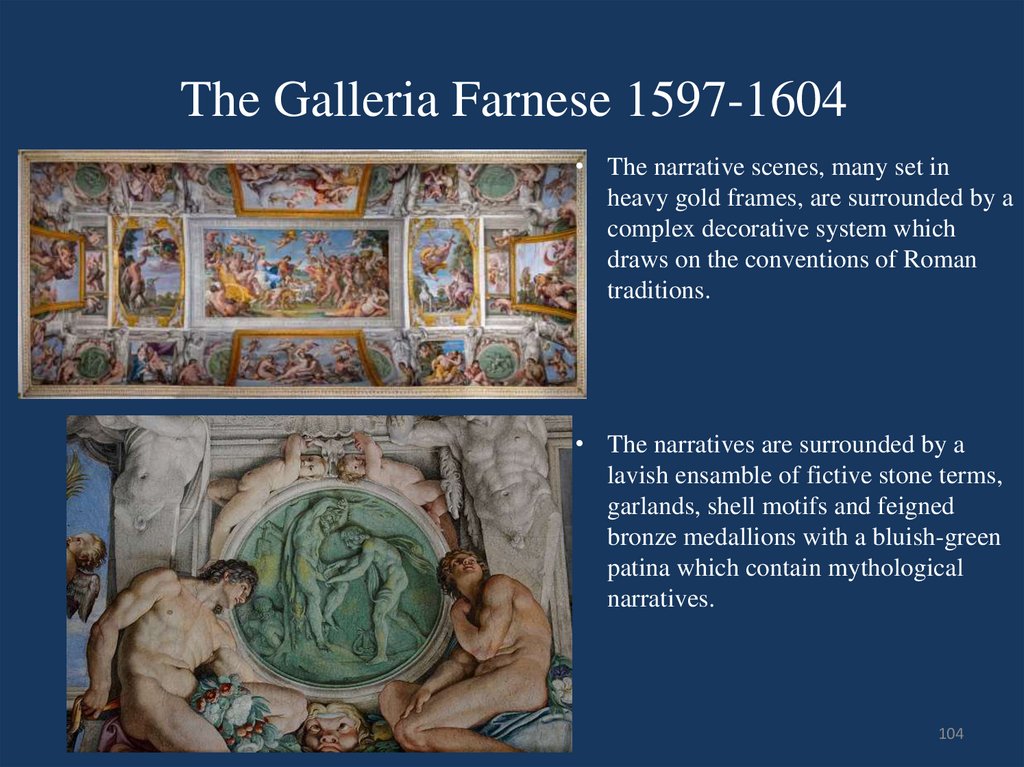

104. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

• The narrative scenes, many set inheavy gold frames, are surrounded by a

complex decorative system which

draws on the conventions of Roman

traditions.

• The narratives are surrounded by a

lavish ensamble of fictive stone terms,

garlands, shell motifs and feigned

bronze medallions with a bluish-green

patina which contain mythological

narratives.

104

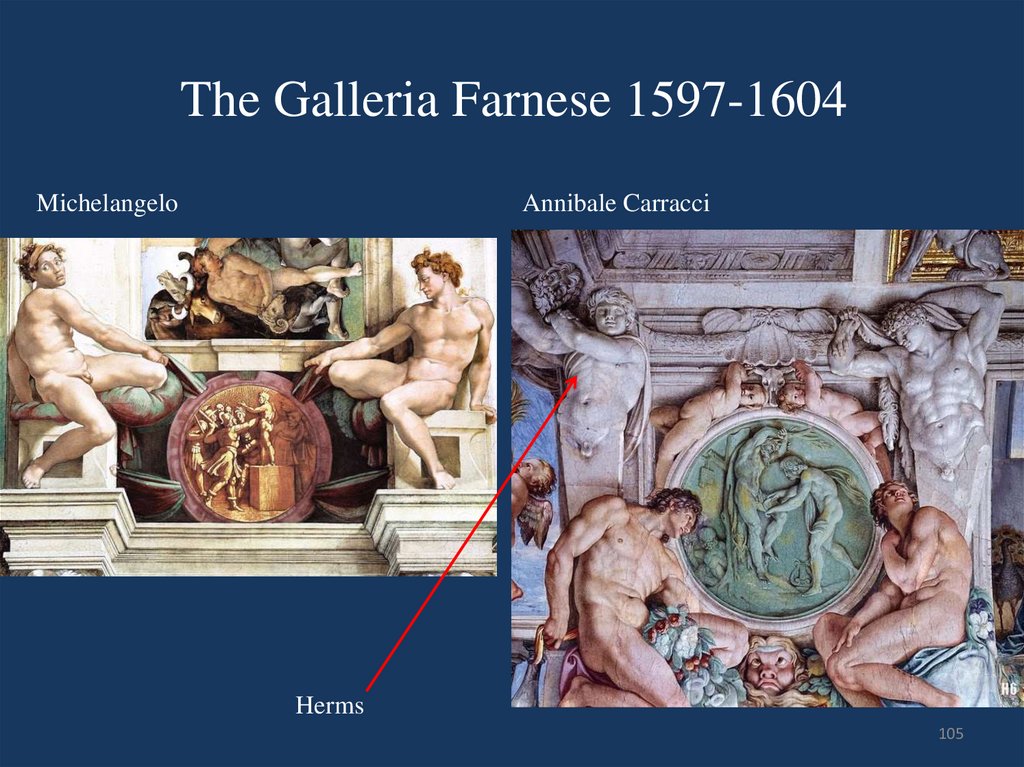

105. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

MichelangeloAnnibale Carracci

Herms

105

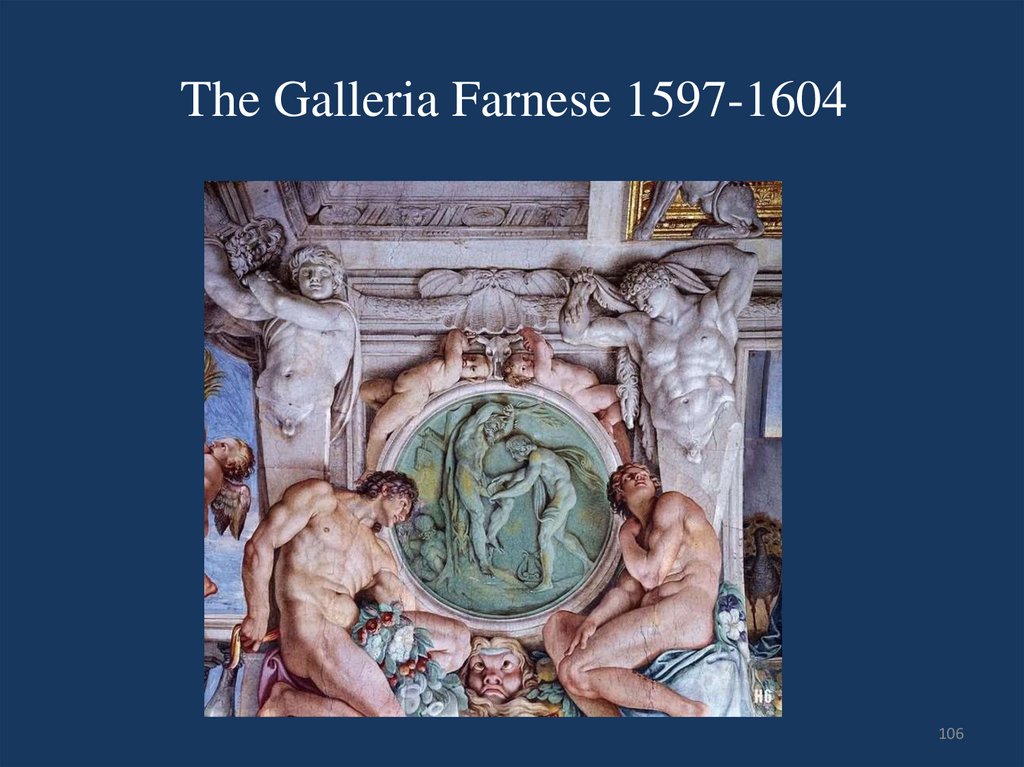

106. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

106107. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

107108. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

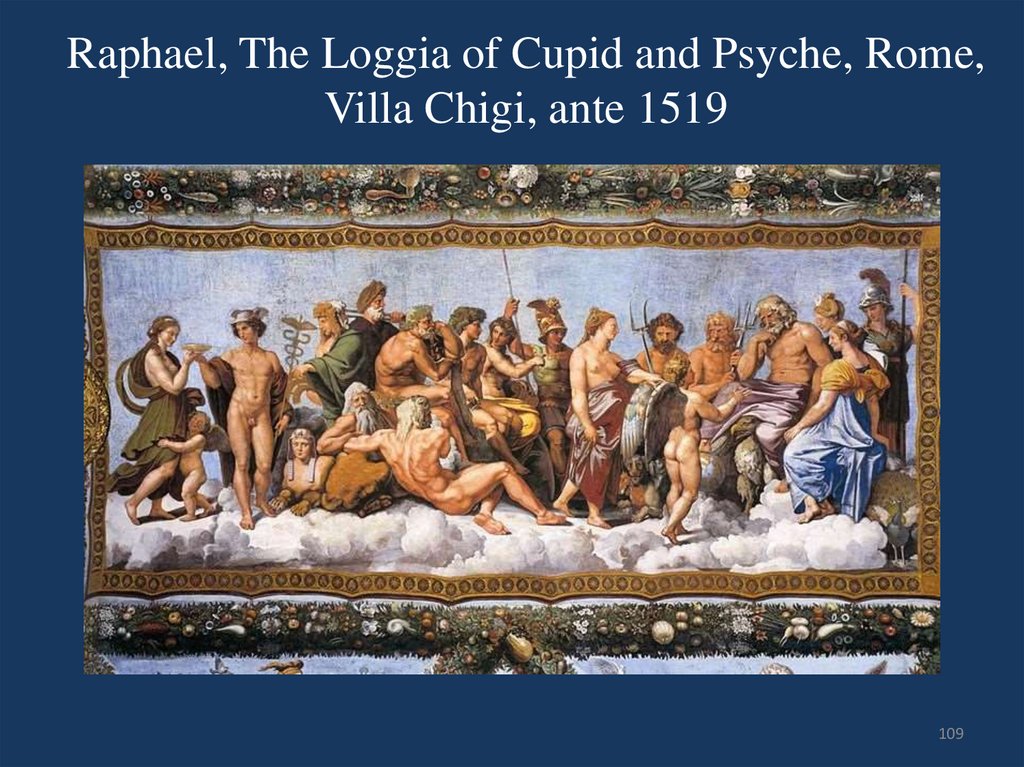

108109. Raphael, The Loggia of Cupid and Psyche, Rome, Villa Chigi, ante 1519

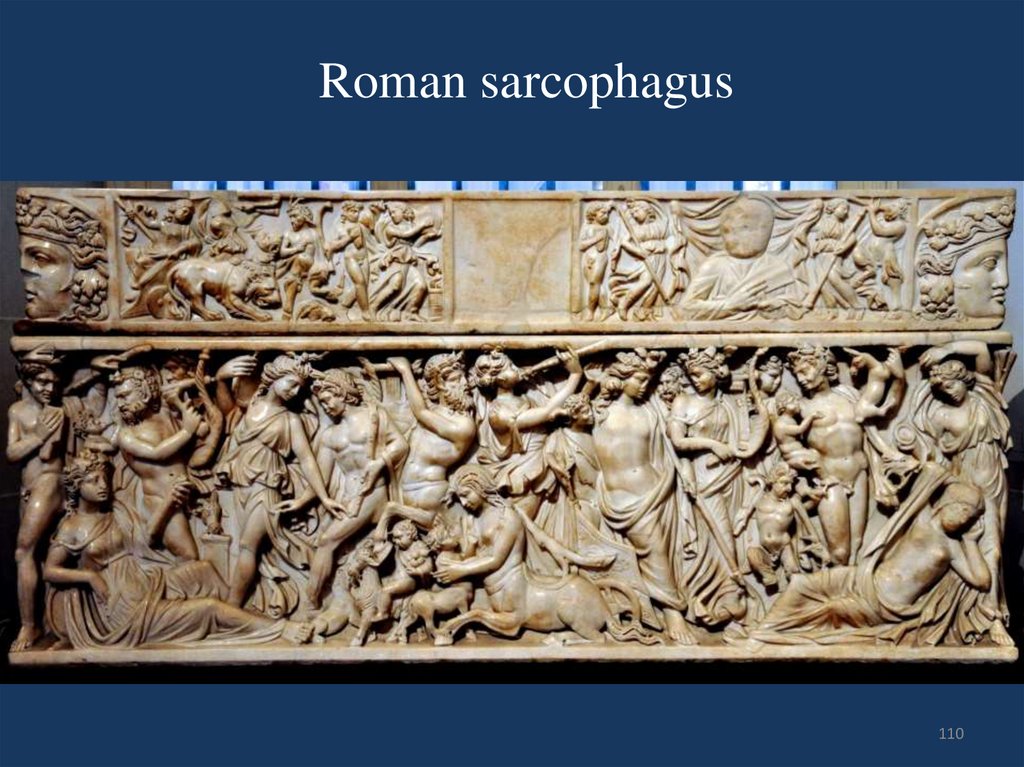

109110. Roman sarcophagus

110111. The Galleria Farnese, 1597-1604

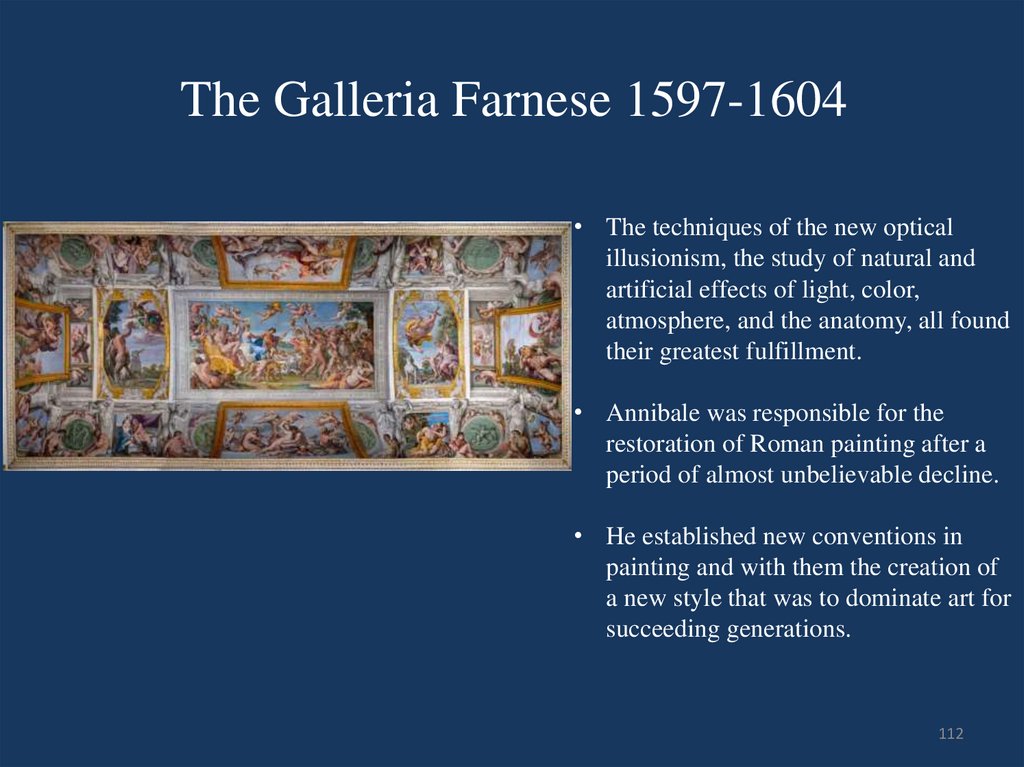

111112. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

• The techniques of the new opticalillusionism, the study of natural and

artificial effects of light, color,

atmosphere, and the anatomy, all found

their greatest fulfillment.

• Annibale was responsible for the

restoration of Roman painting after a

period of almost unbelievable decline.

• He established new conventions in

painting and with them the creation of

a new style that was to dominate art for

succeeding generations.

112

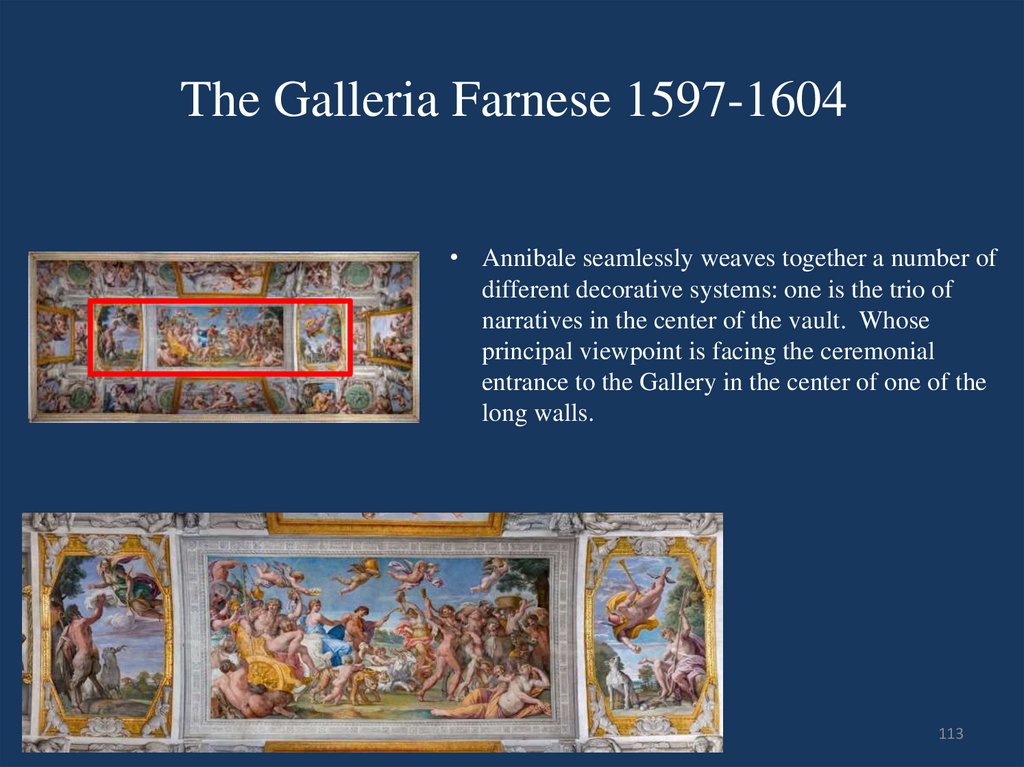

113. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

• Annibale seamlessly weaves together a number ofdifferent decorative systems: one is the trio of

narratives in the center of the vault. Whose

principal viewpoint is facing the ceremonial

entrance to the Gallery in the center of one of the

long walls.

113

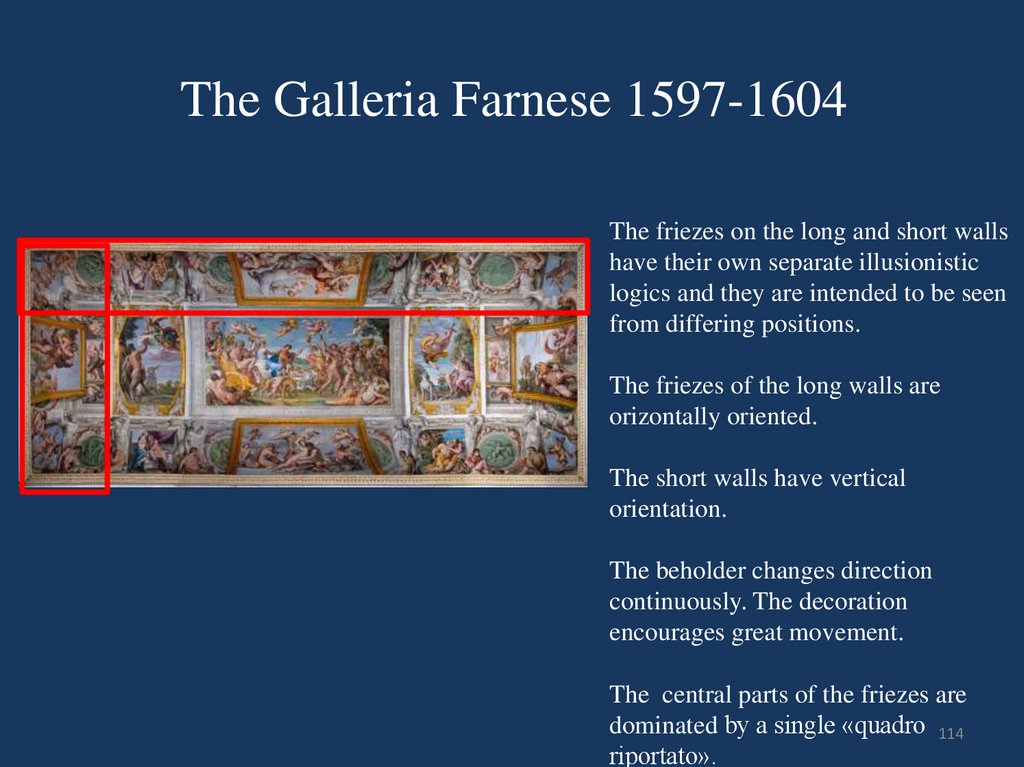

114. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

The friezes on the long and short wallshave their own separate illusionistic

logics and they are intended to be seen

from differing positions.

The friezes of the long walls are

orizontally oriented.

The short walls have vertical

orientation.

The beholder changes direction

continuously. The decoration

encourages great movement.

The central parts of the friezes are

dominated by a single «quadro 114

riportato».

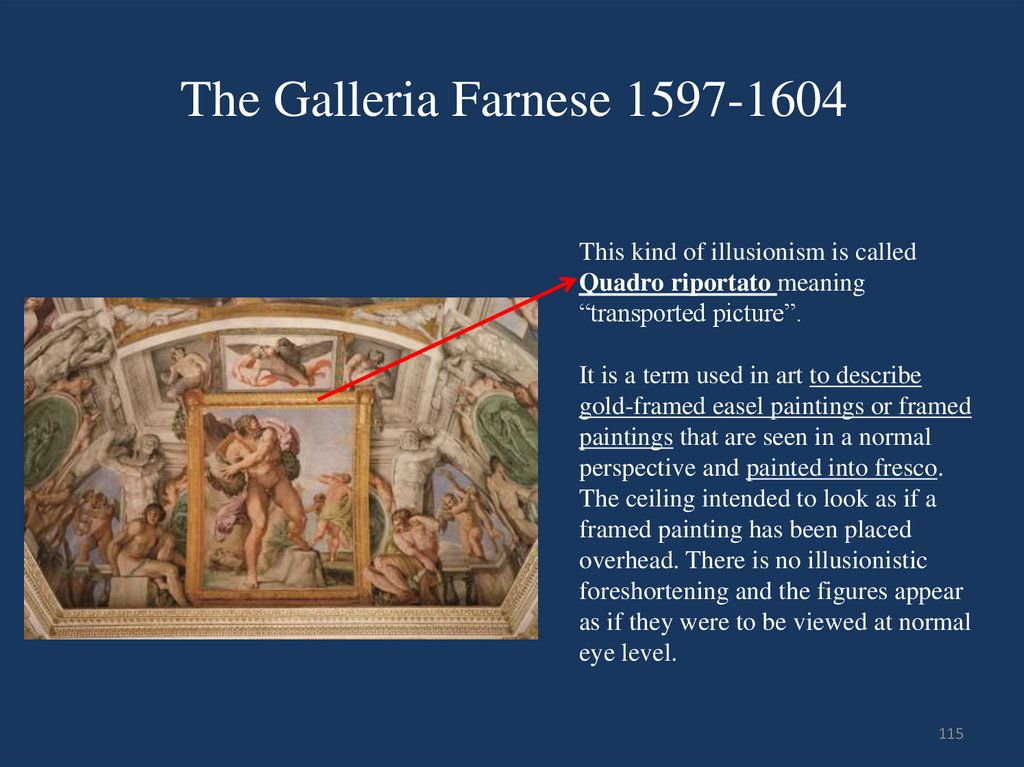

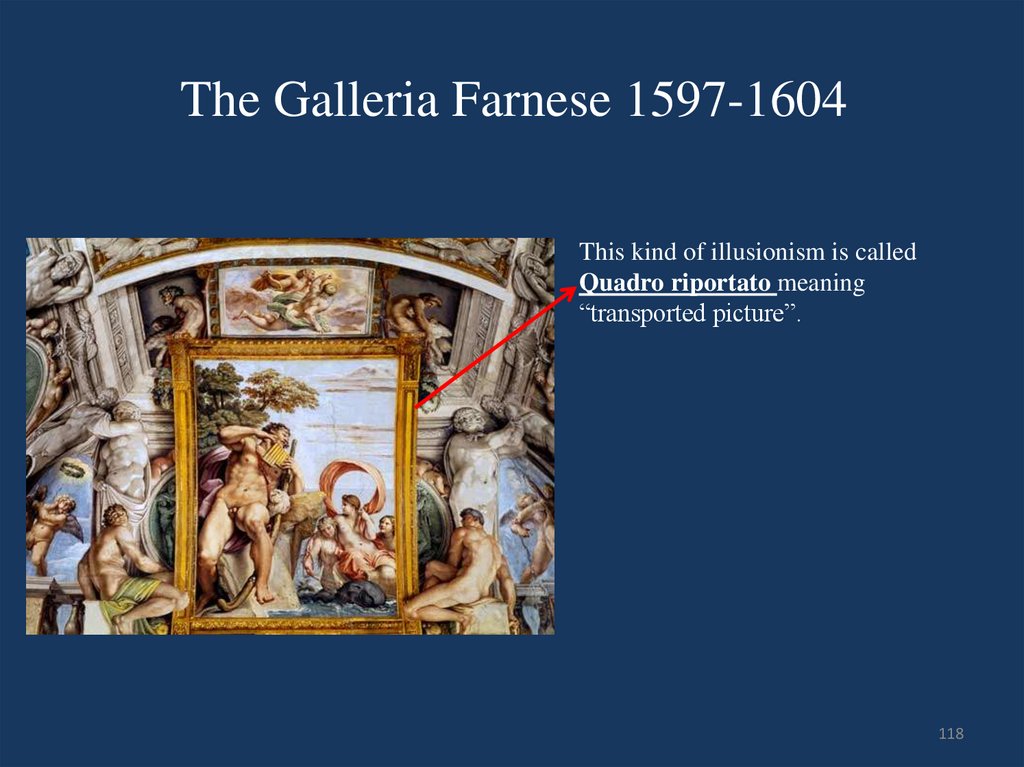

115. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

This kind of illusionism is calledQuadro riportato meaning

“transported picture”.

It is a term used in art to describe

gold-framed easel paintings or framed

paintings that are seen in a normal

perspective and painted into fresco.

The ceiling intended to look as if a

framed painting has been placed

overhead. There is no illusionistic

foreshortening and the figures appear

as if they were to be viewed at normal

eye level.

115

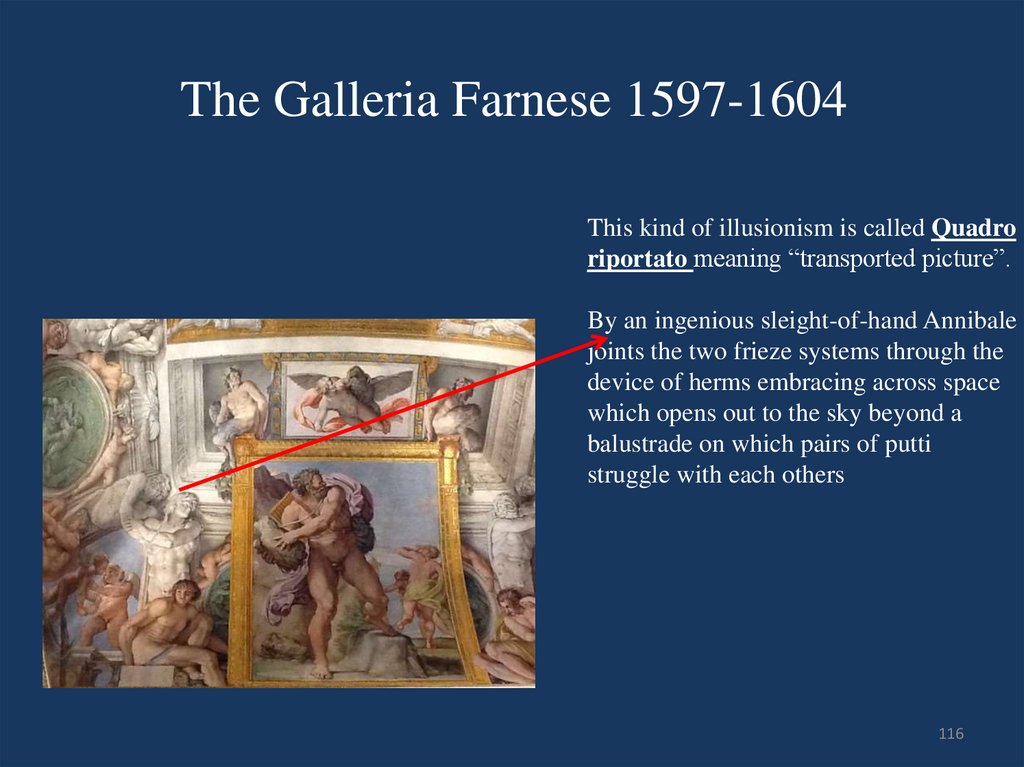

116. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

This kind of illusionism is called Quadroriportato meaning “transported picture”.

By an ingenious sleight-of-hand Annibale

joints the two frieze systems through the

device of herms embracing across space

which opens out to the sky beyond a

balustrade on which pairs of putti

struggle with each others

116

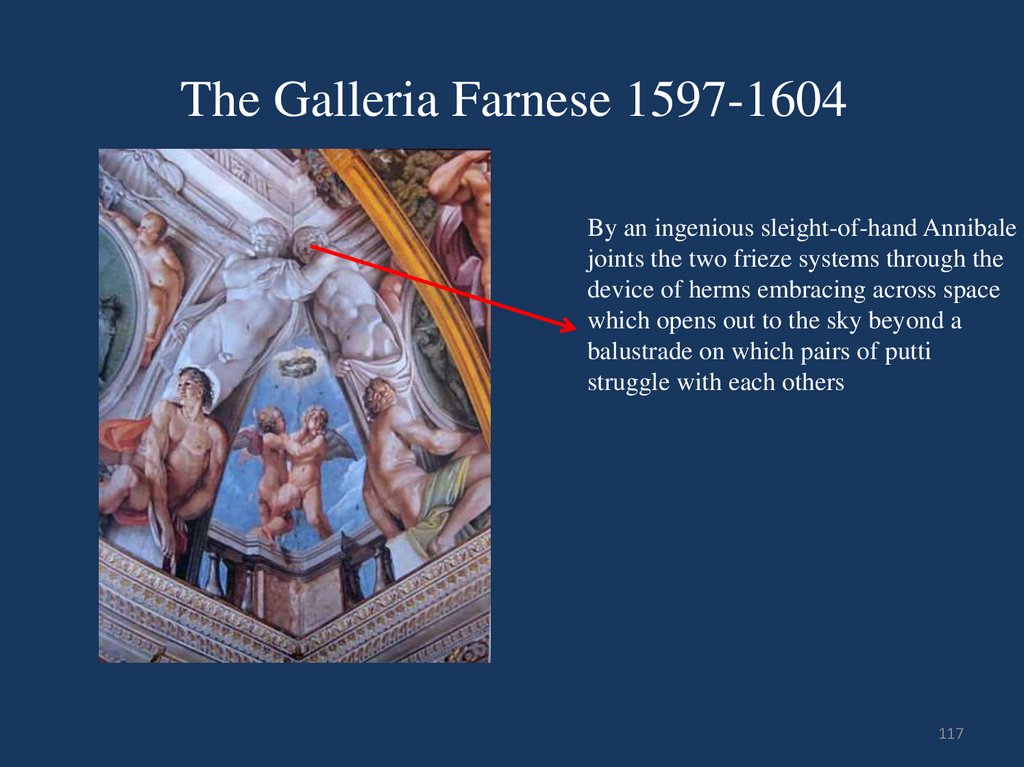

117. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

By an ingenious sleight-of-hand Annibalejoints the two frieze systems through the

device of herms embracing across space

which opens out to the sky beyond a

balustrade on which pairs of putti

struggle with each others

117

118. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

This kind of illusionism is calledQuadro riportato meaning

“transported picture”.

118

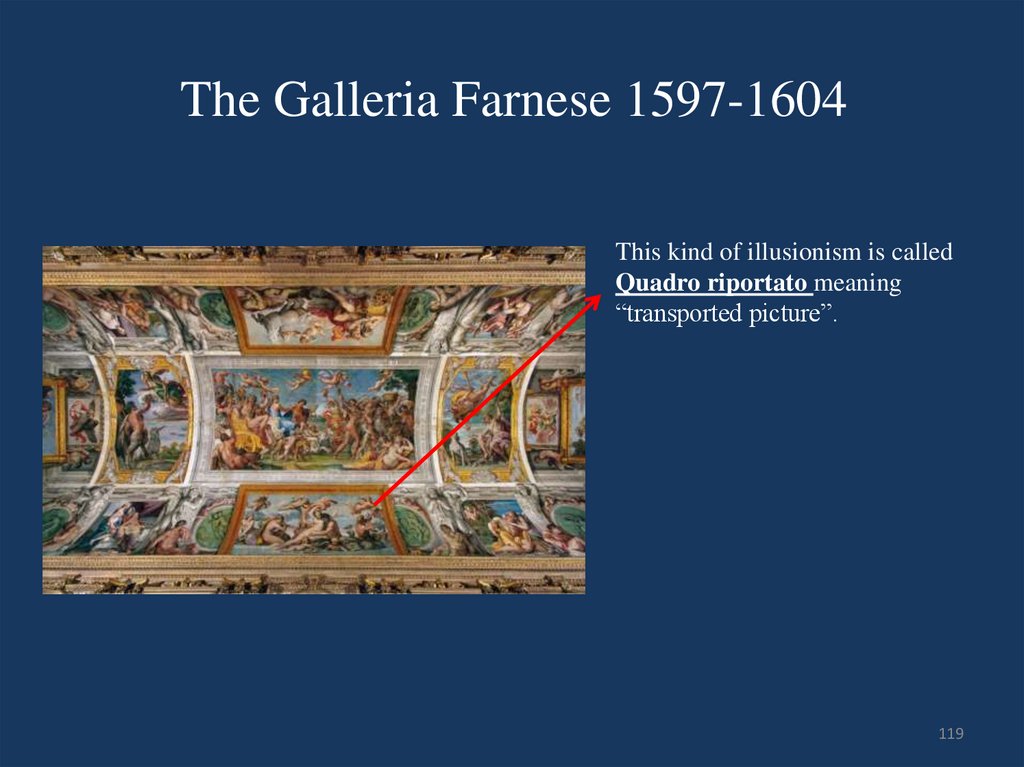

119. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

This kind of illusionism is calledQuadro riportato meaning

“transported picture”.

119

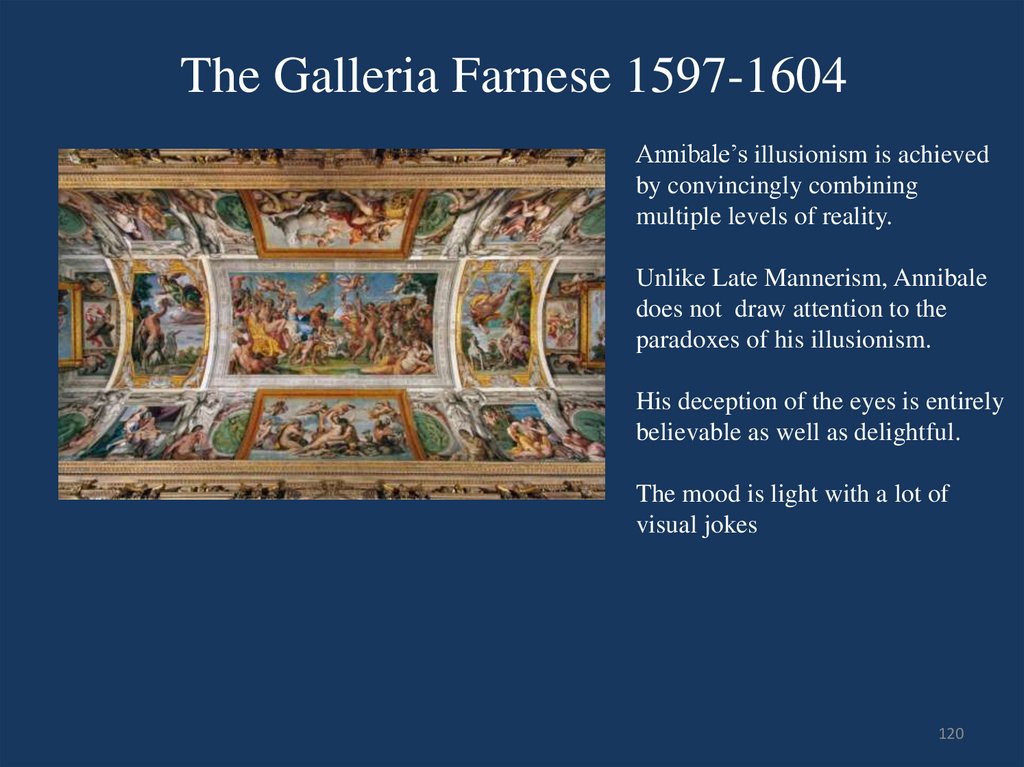

120. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

Annibale’s illusionism is achievedby convincingly combining

multiple levels of reality.

Unlike Late Mannerism, Annibale

does not draw attention to the

paradoxes of his illusionism.

His deception of the eyes is entirely

believable as well as delightful.

The mood is light with a lot of

visual jokes

120

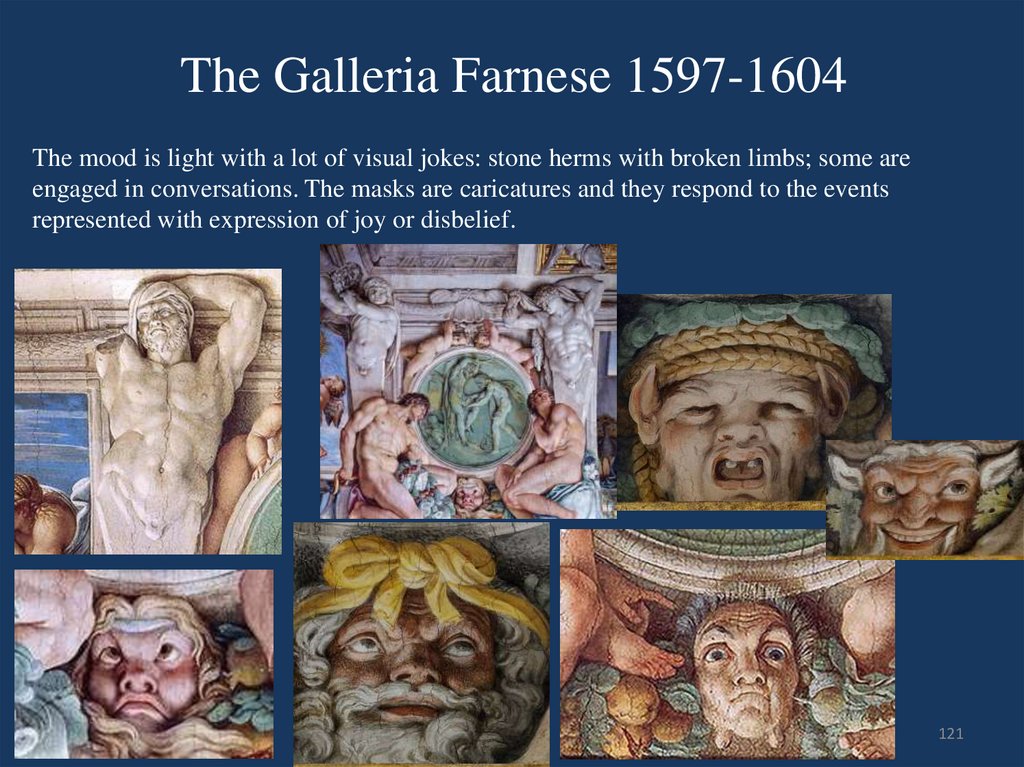

121. The Galleria Farnese 1597-1604

The mood is light with a lot of visual jokes: stone herms with broken limbs; some areengaged in conversations. The masks are caricatures and they respond to the events

represented with expression of joy or disbelief.

121

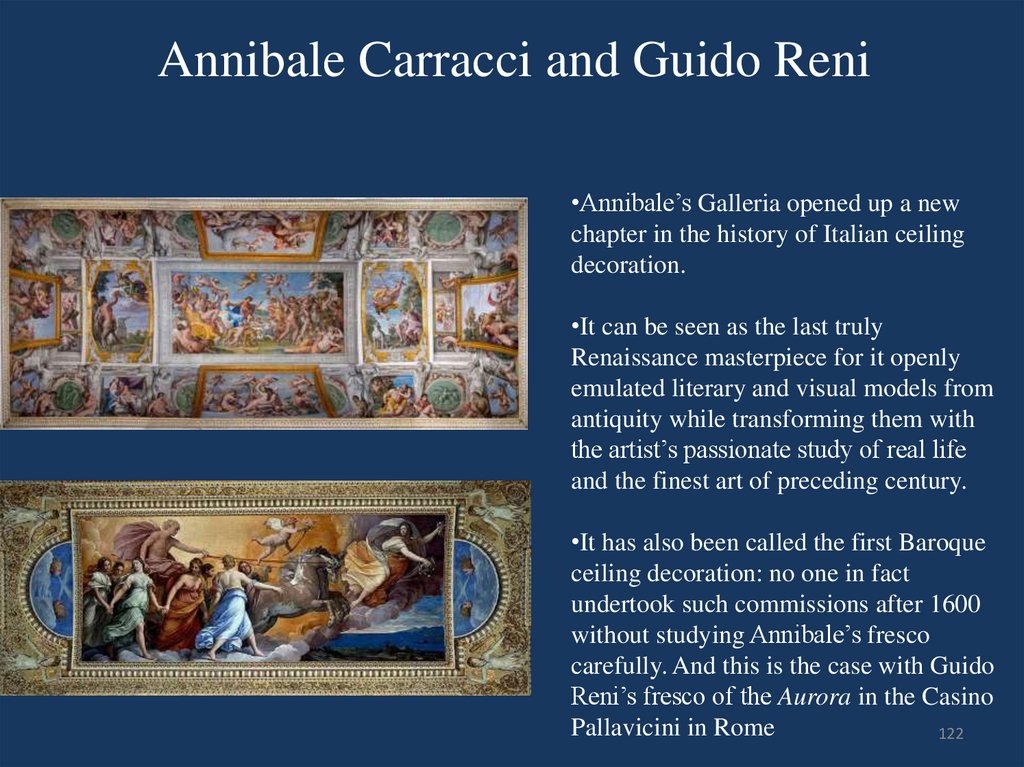

122. Annibale Carracci and Guido Reni

•Annibale’s Galleria opened up a newchapter in the history of Italian ceiling

decoration.

•It can be seen as the last truly

Renaissance masterpiece for it openly

emulated literary and visual models from

antiquity while transforming them with

the artist’s passionate study of real life

and the finest art of preceding century.

•It has also been called the first Baroque

ceiling decoration: no one in fact

undertook such commissions after 1600

without studying Annibale’s fresco

carefully. And this is the case with Guido

Reni’s fresco of the Aurora in the Casino

Pallavicini in Rome

122