Similar presentations:

Cultural relativism

1.

2.

PHIL210 ETHICSREVISION

Anthi Chrysanthou PhD

Week 13/Teaching Session 26 – December 30th, 2023

ac00@aubmed.ac.cy | American University of Beirut

3. Cultural relativism

CULTURAL RELATIVISM4.

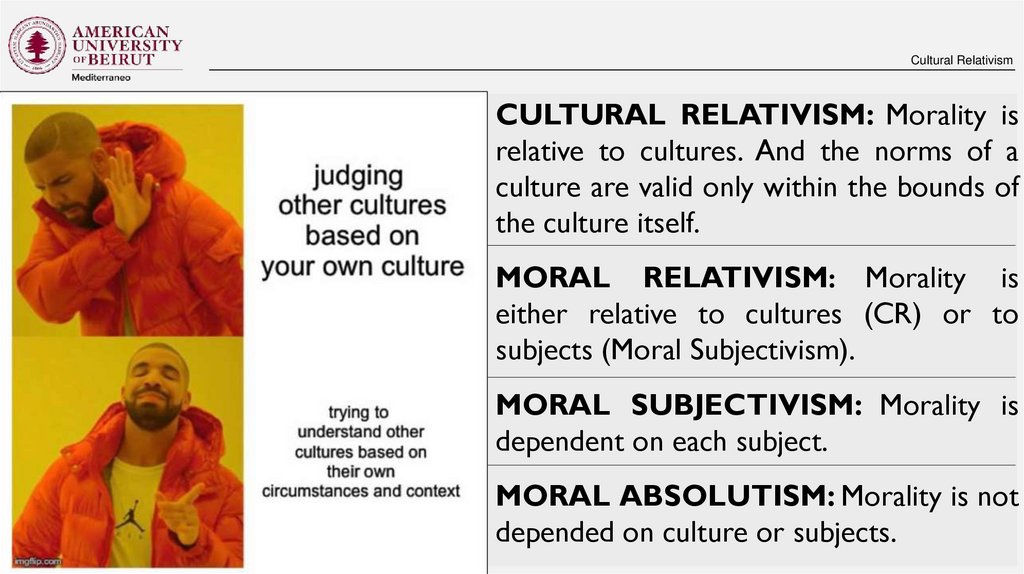

Cultural RelativismCULTURAL RELATIVISM: Morality is

relative to cultures. And the norms of a

culture are valid only within the bounds of

the culture itself.

MORAL RELATIVISM: Morality is

either relative to cultures (CR) or to

subjects (Moral Subjectivism).

MORAL SUBJECTIVISM: Morality is

dependent on each subject.

MORAL ABSOLUTISM: Morality is not

depended on culture or subjects.

5.

Cultural RelativismArgument in favor of Cultural Relativism

1. Different cultures have different moral codes.

2. Therefore, there is no objective truth in morality.

Right and wrong are only matters of opinion, and

opinions vary from culture to culture.

6.

Cultural RelativismDISADVANTAGES OF CULTURAL RELATIVISM

1. If morality is dependent on the culture that

individuals belong to, then there follows an

absurd consequence: individuals are not entitled

to criticize the practices of cultures that they

don’t belong to, even though these practices may

appear intuitively wrong.

7.

Cultural RelativismDescriptive Cultural Relativism: The difference between what is

considered good and bad between different cultures.

Absolute cultural relativism indicates that whatever activities are

practiced within a culture, no matter how weird and dangerous

they appear to be, should not be questioned by other cultures.

Critical cultural relativism asks questions about cultural practices

and why they are practiced. It seeks answers about the cultural

practices in line with who is accepting them and why they are

doing so.

8.

Cultural RelativismDISADVANTAGES OF CULTURAL RELATIVISM

2. Not only individuals can’t criticize the

practices of cultures that they don’t belong to,

but also they cannot criticize their own culture.

How can we criticize our own culture if there is

not some moral standard to appeal to?

9.

Cultural RelativismDISADVANTAGES OF CULTURAL RELATIVISM

3. The idea of moral progress and reform is

considered invalid. For if morality depends on

culture, then it depends on the culture’s moral

codes at a certain time.

10.

Cultural RelativismOBJECTIONS TO CULTURAL RELATIVISM

1.There might be less disagreement in

values than it may seem.

2.There exists a number of universal

values across cultures.

3.Relativism ignores diversity within a

culture.

11.

Cultural RelativismETHNOCENTRISM

A culture and its moral

values are superior to

another. The customs of

other societies are

morally inferior to our

own.

12.

Cultural RelativismImplications of Ethical Relativism

• If ethical truth is determined by

personal opinion or cultural ideals,

then it's impossible for one's personal

ethical opinions or a culture's ideals to

ever be mistaken. It can be argued,

however, that some practices are

wrong.

• The moral views of all individuals or all

cultures are equally good.

• Moral progress is impossible.

13. KANT

14.

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of MoralsThe Good Will

“Nothing can possibly be conceived in the world, or even out of it, which can be

called good, without qualification, except a good will.”

Kant claimed that the only thing that is good in all circumstances is the good will.

The good will: the ability to reliably know what your duty is and a steady

commitment to doing your duty for its own sake.

[Intrinsic value. The outcome doesn’t matter. Deontology and not

consequentialism.]

Moral Worth: An action possesses moral worth if and only if it is truly

praiseworthy. Kant claimed that the only actions that possess moral worth are

actions performed from the good will.

15.

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of MoralsKant makes three claims:

First: That an action must be done from duty in order

to have moral worth.

Second: That an action done from duty, is morally

worthy based on the maxim according to which we

decided to act in this way, and not in its purpose.

Thirdly, Kant claims that: “Duty is the necessity of

acting from respect for the law.”.

16.

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals“An action must be done from duty in order to have

moral worth.”

Three kinds of motivation:

1) *Duty*

2) Inclination

3) Self – interest

17.

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of MoralsMaxim: The Maxim is a subjective principle of volition, the way that

you describe a specific act to yourself. This description is subjective to

you, the subject, and it describes how you desire to behave in a

specific situation.

“Duty is the necessity of acting from respect for the law. […]Now an

action done from duty must wholly exclude the influence of inclination

and with it every object of the will, so that nothing remains which can

determine the will except objectively the law, and subjectively pure

respect for this practical law, and consequently the maxim * that I

should follow this law even to the thwarting of all my inclinations.”

18.

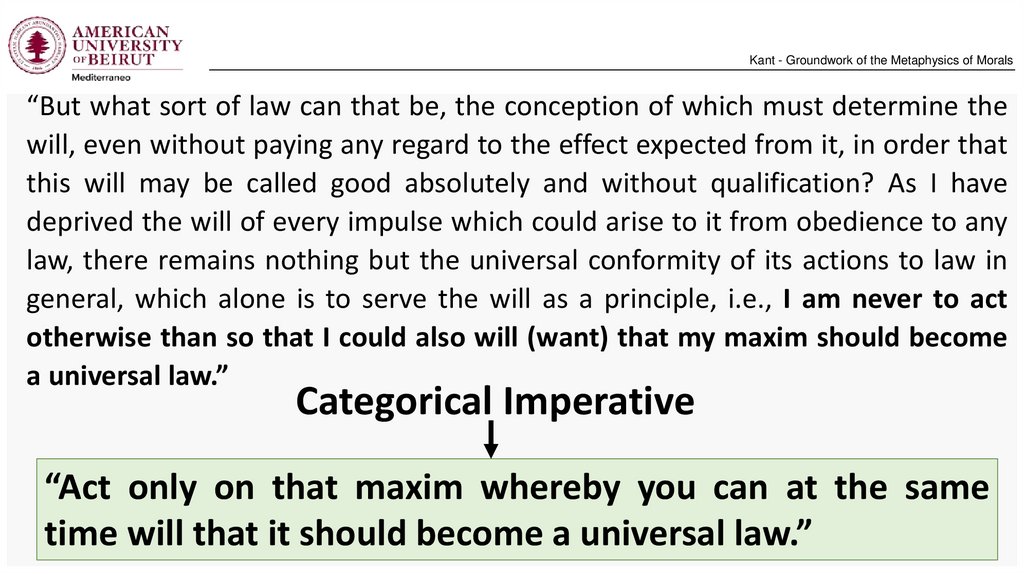

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals“But what sort of law can that be, the conception of which must determine the

will, even without paying any regard to the effect expected from it, in order that

this will may be called good absolutely and without qualification? As I have

deprived the will of every impulse which could arise to it from obedience to any

law, there remains nothing but the universal conformity of its actions to law in

general, which alone is to serve the will as a principle, i.e., I am never to act

otherwise than so that I could also will (want) that my maxim should become

a universal law.”

Categorical Imperative

“Act only on that maxim whereby you can at the same

time will that it should become a universal law.”

19.

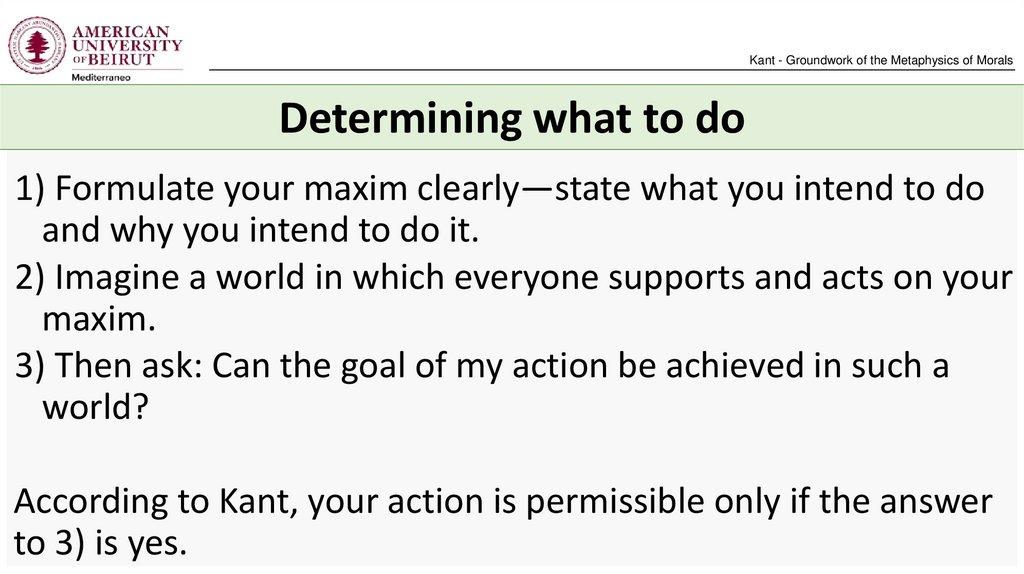

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of MoralsDetermining what to do

1) Formulate your maxim clearly—state what you intend to do

and why you intend to do it.

2) Imagine a world in which everyone supports and acts on your

maxim.

3) Then ask: Can the goal of my action be achieved in such a

world?

According to Kant, your action is permissible only if the answer

to 3) is yes.

20.

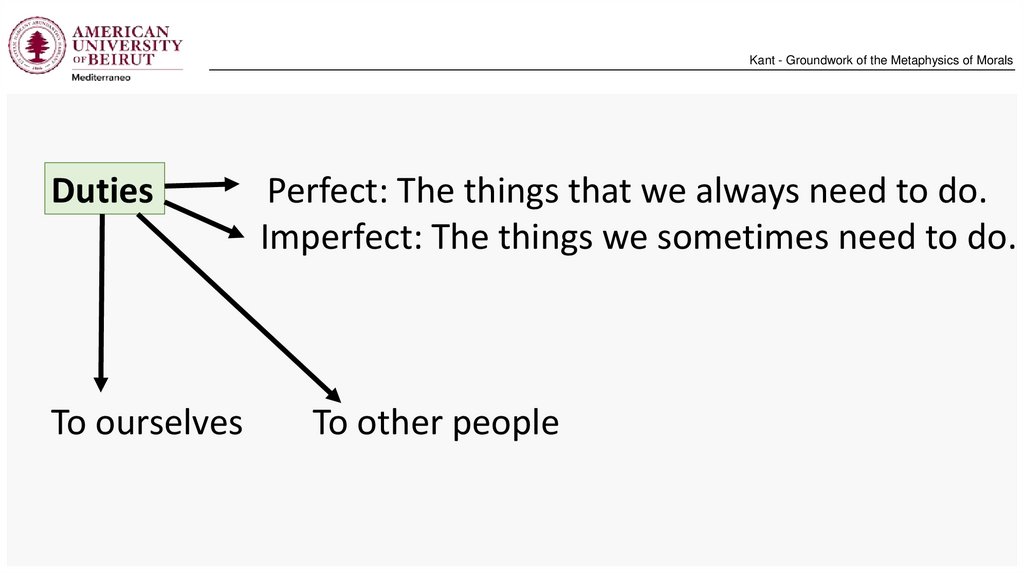

Kant - Groundwork of the Metaphysics of MoralsDuties

To ourselves

Perfect: The things that we always need to do.

Imperfect: The things we sometimes need to do.

To other people

21. HEGEL

22.

Hegel – The Ethical LifeGEIST = SPIRIT [MIND]

Something between spirit and mind Connotations more mental than

the word “spirit” and more spiritual than the world “mind”.

What is Geist? The ultimate essence of being, the stuff of existence. A

principle of motion, or self-consciousness coming to know itself.

[Heraclitus (Greek philosopher): “No man ever steps in the same river

twice. For it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”]

The world is always in movement. The movement that Spirit represents is

always heading towards greater freedom.

23.

Hegel – The Ethical LifeWorld History: The unfolding of Spirit which always has a progressive movement. The

development of Spirit towards self-awareness.

Goal: the “Idea”

The synthesis of subjectivity and objectivity, of matter and spirit.

For the Idea to become a reality it needs human activity.

THREE STAGES OF SPIRIT

1. Spirit is completely immersed in nature, it’s everywhere around in nature.

2. Spirit emerges into self-consciousness and freedom. It reflects on itself.

3. Spirit achieves universality. It unifies the subjective with the objective.

Highest achievement of Spirit To know itself.

Hegel calls this state of self-awareness of everything “the Absolute”

So his philosophy became known as “Absolute Idealism”.

24.

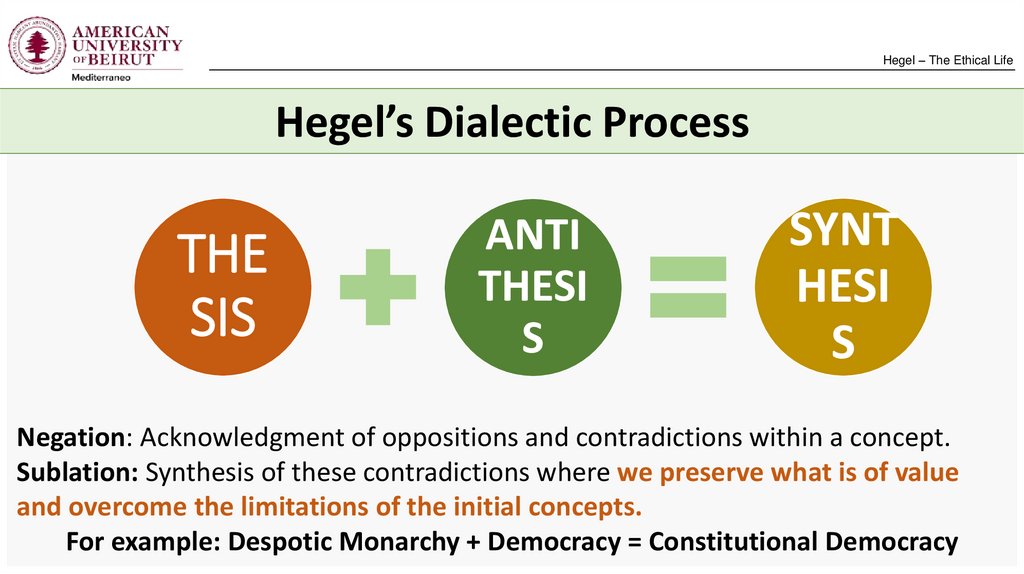

Hegel – The Ethical LifeHegel’s Dialectic Process

THE

SIS

ANTI

THESI

S

SYNT

HESI

S

Negation: Acknowledgment of oppositions and contradictions within a concept.

Sublation: Synthesis of these contradictions where we preserve what is of value

and overcome the limitations of the initial concepts.

For example: Despotic Monarchy + Democracy = Constitutional Democracy

25.

Hegel – The Ethical LifeMaster – Servant Dialectic

In Phenomenology of Spirit par.178 and forward.

Self-consciousness emerges through being faced with another consciousness, the “other”.

Consciousness

of the self

(Being-for-self)

Self-existence acknowledged

by other human beings

(Being-for-others)

MASTER

SERVA

NT

26.

Hegel – The Ethical Life“Sittlichkeit” – The Ethical Life

It has a Triadic Structure: Family - Civil Society - State

Family: Important role for instilling values and promoting personal

relationships.

Importance of marriage as an institution.

Civil Society: It consists of individual rights, social institutions and economic

activity.

Dangers: Unregulated Capitalism and Abstract Individualism.

State: “Man owes his entire existence to the State.” The peak of the ethical

system. Not just government but all the dimensions of cultural life, arts,

education, religion, ethics. Important role in judging conflicts.

27.

Hegel – The Ethical LifeStructures and Institutions which promote freedom so that

Ethical Life is possible (because not all social or political

institutions count as ethical)

family life founded on love (not violence).

a civil society in which the right to own and exchange property, and the

freedom to pursue the occupation of one’s own choice, are guaranteed.

courts of law in which justice is upheld in public and on the basis of published

laws.

a public authority and corporations that protect members of society and

defend their rights.

a state in which the monarchical, executive, and legislative powers are

distinguished and we have assemblies responsible for legislation.

28. HEDONISM

29.

Hedonism – Epicurus and AristippusHedonism

The word “Hedonism” comes from the Greek word

hēdonē, which means “pleasure”.

Hedonism: the view that our life is good if it is filled

with pleasure and is free of pain.

Pleasure is the only thing that is intrinsically good for

people.

30.

Hedonism – Epicurus and AristippusPsychological Hedonism and Ethical Hedonism

Psychological Hedonism: Suggests that everything we do, we do it so we

ultimately gain pleasure.

Ethical Hedonism: Suggests that only pleasure has worth or value. Only pleasure

is an intrinsic good.

Normative Hedonism: the idea that pleasure should be people’s primary

motivation.

Motivational Hedonism: only pleasure and pain cause people to do what they do.

Egoistical Hedonism: requires a person to consider only his or her own pleasure

in making choices.

Altruistic Hedonism: the creation of pleasure for all people is the best way to

measure if an action is ethical.

31.

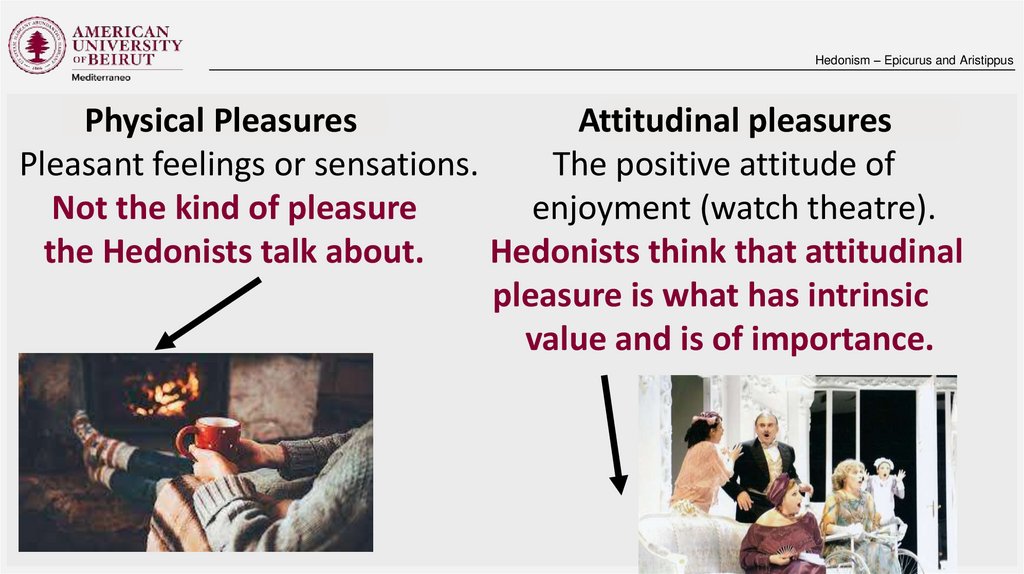

Hedonism – Epicurus and AristippusPhysical Pleasures

Attitudinal pleasures

Pleasant feelings or sensations.

The positive attitude of

Not the kind of pleasure

enjoyment (watch theatre).

the Hedonists talk about.

Hedonists think that attitudinal

pleasure is what has intrinsic

value and is of importance.

32.

Hedonism – Epicurus and AristippusATARAXIA

“The greatest reward of righteousness is peace of mind.”

“The just man is most free from disturbance, while the unjust is full of the utmost

disturbance.”

“There are two kinds of pleasure: one consisting in a state of rest, in which both body

and mind are undisturbed by any kind of pain; the other arising from an agreeable

agitation of the senses, producing a correspondent emotion in the soul. It is upon the

former of these that the enjoyment of life chiefly depends. Happiness may therefore

be said to consist in bodily ease, and mental tranquility.”

33.

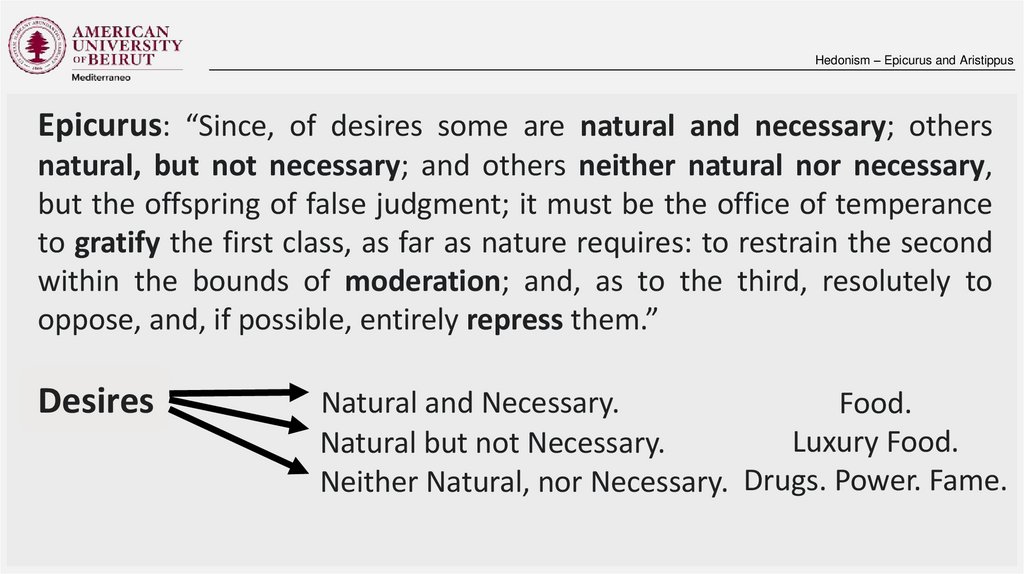

Hedonism – Epicurus and AristippusEpicurus: “Since, of desires some are natural and necessary; others

natural, but not necessary; and others neither natural nor necessary,

but the offspring of false judgment; it must be the office of temperance

to gratify the first class, as far as nature requires: to restrain the second

within the bounds of moderation; and, as to the third, resolutely to

oppose, and, if possible, entirely repress them.”

Desires

Natural and Necessary.

Food.

Luxury Food.

Natural but not Necessary.

Neither Natural, nor Necessary. Drugs. Power. Fame.

34. utilitarianism

UTILITARIANISM35.

Utilitarianism – Bentham and MillFelicific Calculus

The Felicific Calculus measures an action based on its tendency to produce pleasure or pain on seven

circumstances. The following are the circumstances to be consulted:

Intensity — what is the strength of the feeling of pleasure or pain that would result from the action?

Duration — how long would the pleasure or pain last after the action?

Certainty/Uncertainty — how sure can we be that the action will result in pleasure or pain?

Propinquity/Remoteness — is the pleasure or pain immediate, or will it be delayed to another future

time?

Fecundity — does the action have the ability to reproduce the same sort of feelings?

Purity — is there a chance that the pleasure of an action will lead to further pain and vice versa?

Extent — how far-reaching is the action regarding people impacted as a result?

Calculate:

1.Winning the lottery.

2.Curing cancer.

36.

Utilitarianism – Bentham and MillGreatest Happiness Principle

“Actions are right in proportion as they

tend to promote happiness, wrong as

they tend to promote the reverse of

happiness. By happiness is intended

pleasure, and the absence of pain; by

unhappiness, pain, and the privation of

pleasure.’”

John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, Ch.2

37.

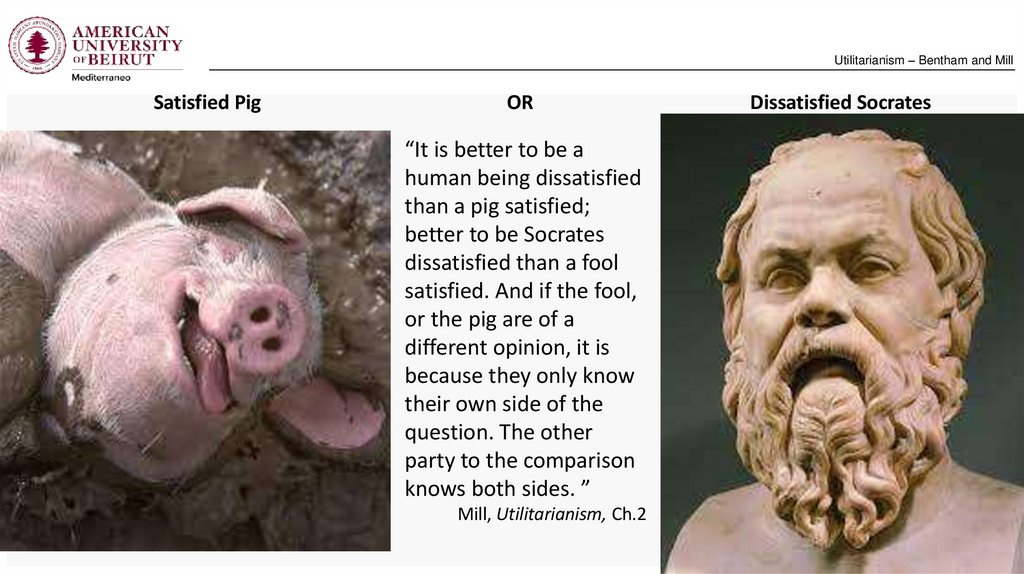

Utilitarianism – Bentham and MillSatisfied Pig

OR

“It is better to be a

human being dissatisfied

than a pig satisfied;

better to be Socrates

dissatisfied than a fool

satisfied. And if the fool,

or the pig are of a

different opinion, it is

because they only know

their own side of the

question. The other

party to the comparison

knows both sides. ”

Mill, Utilitarianism, Ch.2

Dissatisfied Socrates

38.

Utilitarianism – Bentham and MillHigher and Lower Pleasures

We should consider quality as well as quantity of pleasure.

“It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognize the fact that some kinds of

pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. It would be absurd that, while in

estimating all other things quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasure

should be supposed to depend on quantity alone.”

Mill, Utilitarianism, Ch.2

“If I am asked what I mean by difference of quality in pleasures...except [one’s] being greater in

amount, there is but one possible answer. Of two pleasures, if there be one to which all or

almost all who have experience of both give a decided preference, irrespective of any feeling

of moral obligation to prefer it, that is the more desirable pleasure.”

Mill, Utilitarianism, Ch.2

39.

Utilitarianism – Bentham and MillMotivation is Irrelevant to the Action

The motive has nothing to do with the morality of the action:

“He who saves another creature from drowning does what is morally right

whether his motive be duty or the hope of being paid for his trouble”.

Intrinsic or instrumental value of goodness.

Motivation is Relevant to the Agent

Mill acknowledges that there is a difference between someone that is motivated

by true good intentions and someone that will get something in return.

40.

Against UtilitarianismObjection to Utilitarianism

Premise 1: If utilitarianism were true, it would tell us, correctly, which acts are

right and which are wrong.

Premise 2: Utilitarianism tells us that if torturing an innocent child to death

would bring about better consequences than anything else we could do, then

torturing an innocent child to death would be the right thing to do.

Premise 3: Torturing an innocent child to death is always wrong.

Conclusion: Utilitarianism is false.

41.

Against UtilitarianismObjections to Utilitarianism

“Are Consequences all that matter?”

If things other than consequences are important in determining what is right, then

Utilitarianism is incorrect.

Other factors matter:

JUSTICE: Justice requires us to treat people fairly, according to the facts of their particular

situations. If Utilitarianisms requests that we treat someone unfairly, then Utilitarianism can’t

be right.

RIGHTS: We all have rights, and it shouldn’t be ok that someone’s or some people’s rights are

violated in order to produce more happiness or pleasure for other people.

BACKWARD-LOOKING REASONS: Utilitarianism only cares about the consequence and so it

doesn’t look at things that took place in the past and could be relevant to making a decision.

42.

Against UtilitarianismMEASURING UTILITY – PRACTICALLY IMPOSSIBLE

43. Virtue ethics

VIRTUE ETHICS44.

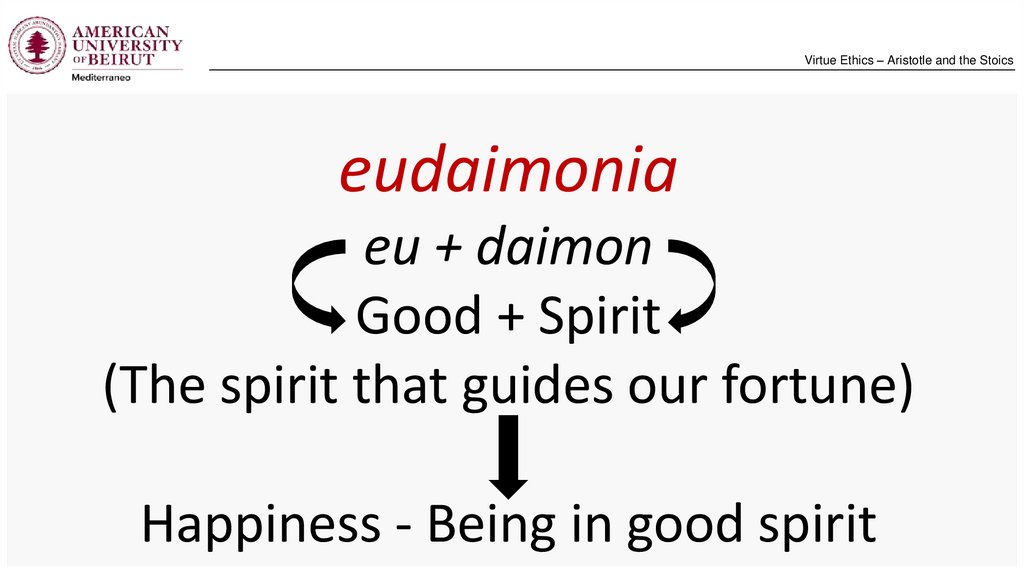

Virtue Ethics – Aristotle and the Stoicseudaimonia

eu + daimon

Good + Spirit

(The spirit that guides our fortune)

Happiness - Being in good spirit

45.

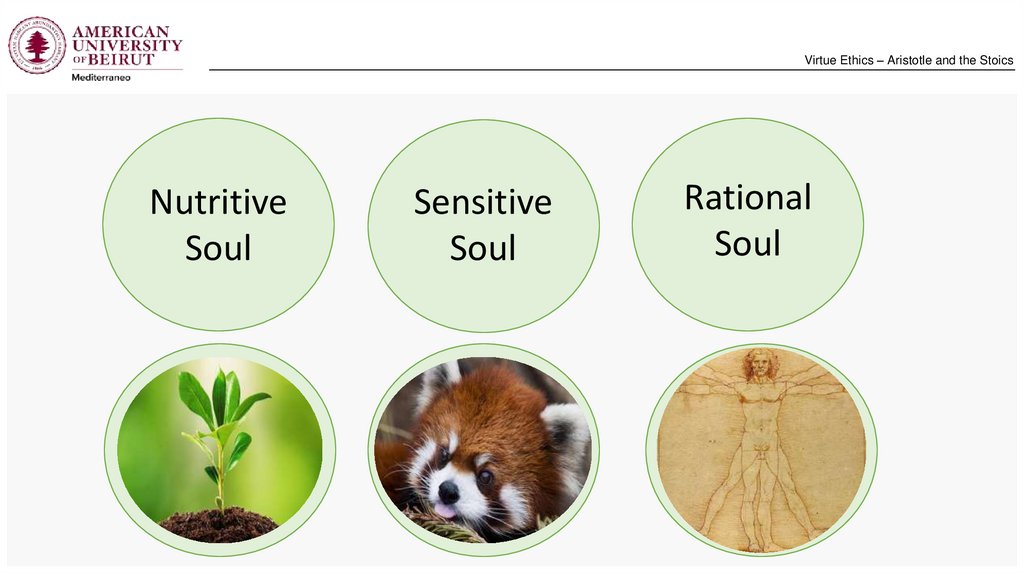

Virtue Ethics – Aristotle and the StoicsNutritive

Soul

Sensitive

Soul

Rational

Soul

46.

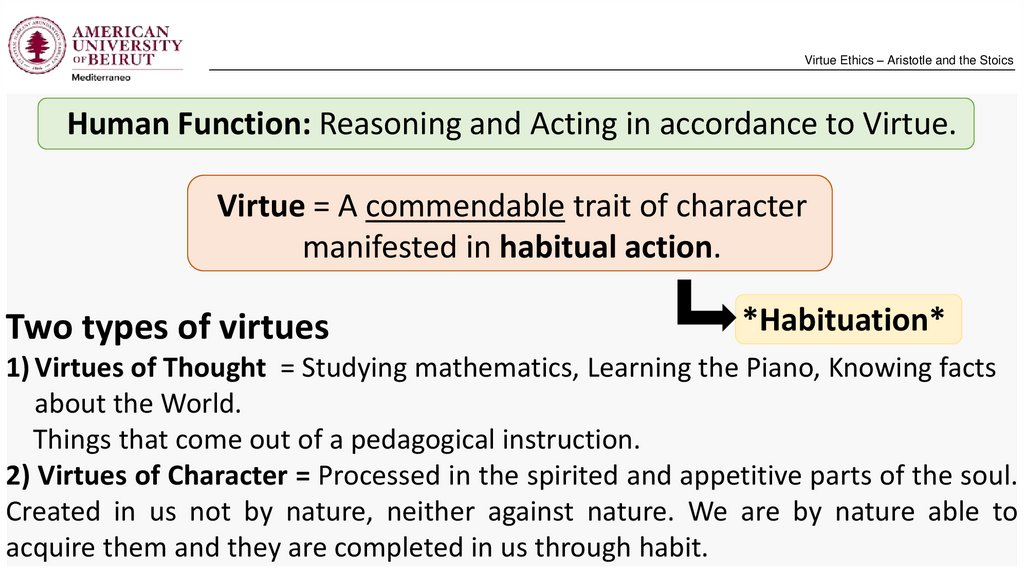

Virtue Ethics – Aristotle and the StoicsHuman Function: Reasoning and Acting in accordance to Virtue.

Virtue = A commendable trait of character

manifested in habitual action.

Two types of virtues

*Habituation*

1) Virtues of Thought = Studying mathematics, Learning the Piano, Knowing facts

about the World.

Things that come out of a pedagogical instruction.

2) Virtues of Character = Processed in the spirited and appetitive parts of the soul.

Created in us not by nature, neither against nature. We are by nature able to

acquire them and they are completed in us through habit.

47.

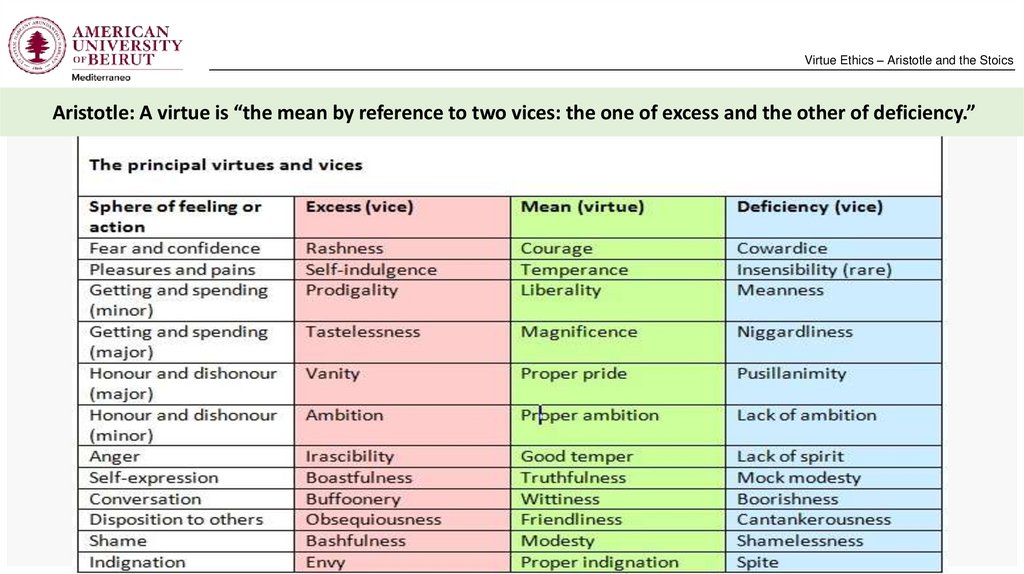

Virtue Ethics – Aristotle and the StoicsAristotle: A virtue is “the mean by reference to two vices: the one of excess and the other of deficiency.”

48.

Virtue Ethics – Aristotle and the StoicsNE, Book II, Ch.4: “The question might be asked,; what we mean by saying that

we must become just by doing just acts, and temperate by doing temperate acts;

for if men do just and temperate acts, they are already just and temperate,

exactly as, if they do what is in accordance with the laws of grammar and of

music, they are grammarians and musicians.”

Even though, to be just and temperate, it is a requirement that you act in

a just and temperate way, it is not a sufficient condition.

NE, Book II, Ch.4: “The agent also must be in a certain condition

when he does them…”

49.

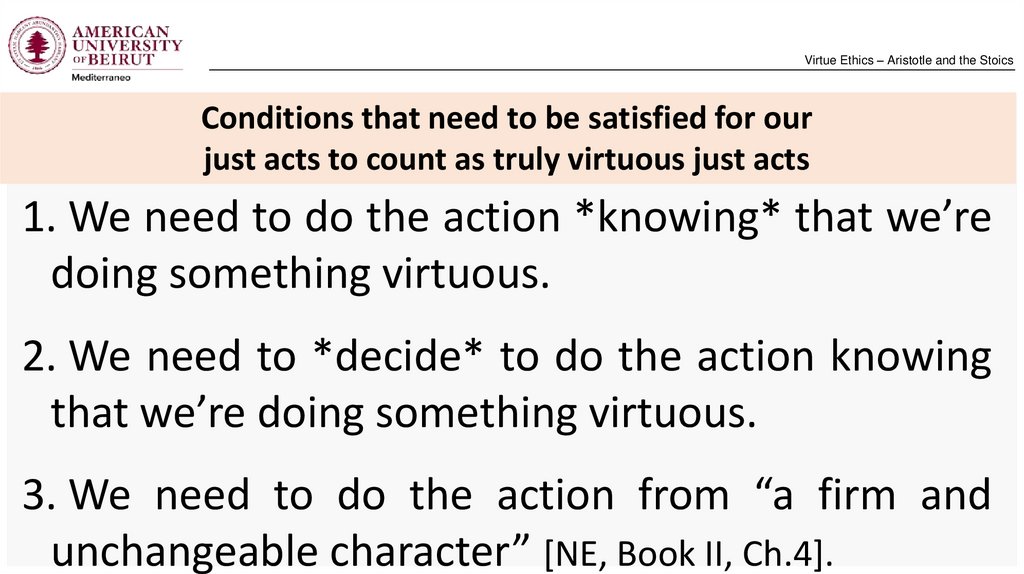

Virtue Ethics – Aristotle and the StoicsConditions that need to be satisfied for our

just acts to count as truly virtuous just acts

1. We need to do the action *knowing* that we’re

doing something virtuous.

2. We need to *decide* to do the action knowing

that we’re doing something virtuous.

3. We need to do the action from “a firm and

unchangeable character” [NE, Book II, Ch.4].

philosophy

philosophy