Similar presentations:

Consumer Behavior

1. Chapter 3

Consumer Behavior2. Introduction

How are consumer preferences used todetermine demand?

How do consumers allocate income to

the purchase of different goods?

How do consumers with limited income

decide what to buy?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

2

3. Introduction

How can we determine the nature ofconsumer preferences for observations

of consumer behavior?

How can cost of living indexes measure

the well-being of consumers?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

3

4. Consumer Behavior - Applications

Consumer Behavior Applications1. How would General Mills determine the

price to charge for a new cereal before

it went to the market?

2. To what extent did the food stamp

program provide individuals with more

food versus merely subsidizing food

they bought anyway?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

4

5. Consumer Behavior

The theory of consumer behavior can beused to help answer these and many

more questions

Theory of consumer behavior

The explanation of how consumers allocate

income to the purchase of different goods

and services

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

5

6. Consumer Behavior

There are three steps involved in thestudy of consumer behavior

1. Consumer Preferences

To describe how and why people prefer one

good to another

2. Budget Constraints

People have limited incomes

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

6

7. Consumer Behavior

3. Given preferences and limited incomes,what amount and type of goods will be

purchased?

What combination of goods will consumers

buy to maximize their satisfaction?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

7

8. Consumer Preferences

How might a consumer compare differentgroups of items available for purchase?

A market basket is a collection of one or

more commodities

Individuals can choose between market

baskets containing different goods

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

8

9. Consumer Preferences – Basic Assumptions

1. Preferences are completeConsumers can rank market baskets

2. Preferences are transitive

If they prefer A to B, and B to C, they must

prefer A to C

3. Consumers always prefer more of any

good to less

More is better

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

9

10. Consumer Preferences

Consumer preferences can berepresented graphically using

indifference curves

Indifference curves represent all

combinations of market baskets that the

person is indifferent to

A person will be equally satisfied with either

choice

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

10

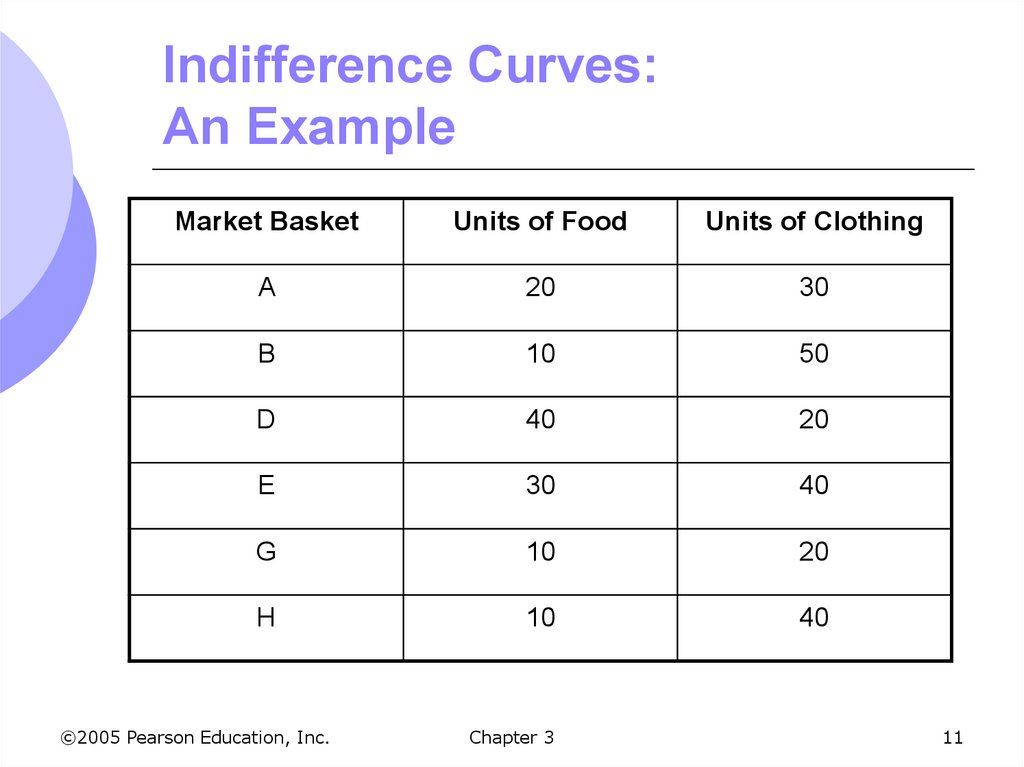

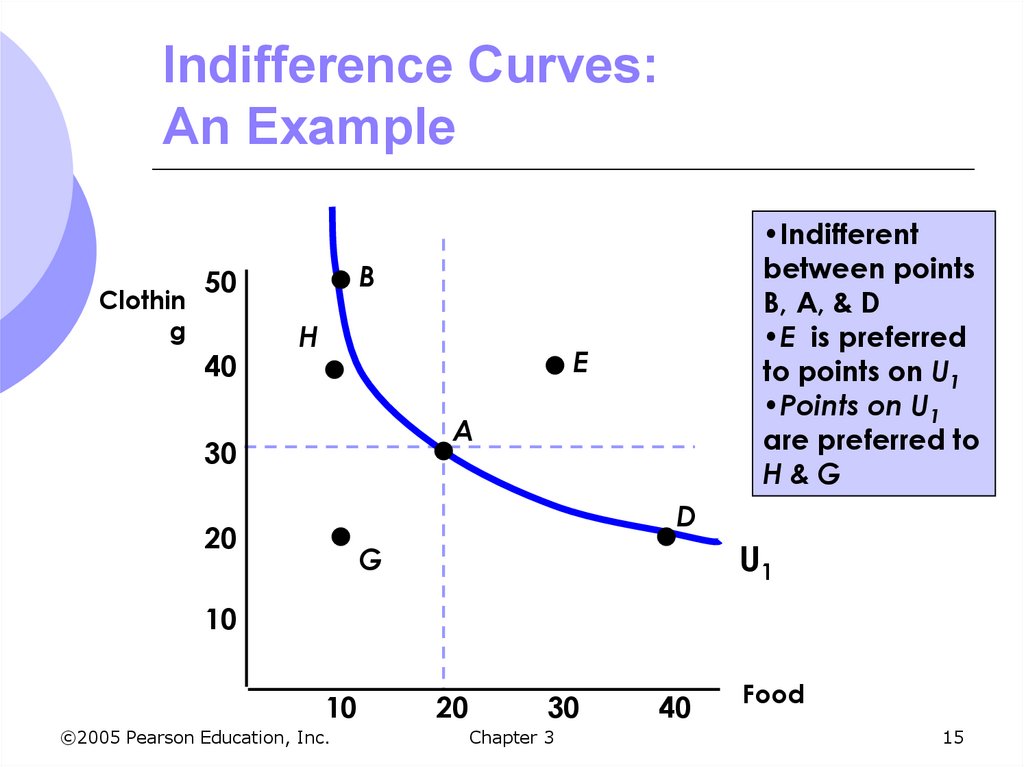

11. Indifference Curves: An Example

Market BasketUnits of Food

Units of Clothing

A

20

30

B

10

50

D

40

20

E

30

40

G

10

20

H

10

40

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

11

12. Indifference Curves: An Example

Graph the points with one good on the xaxis and one good on the y-axisPlotting the points, we can make some

immediate observations about

preferences

More is better

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

12

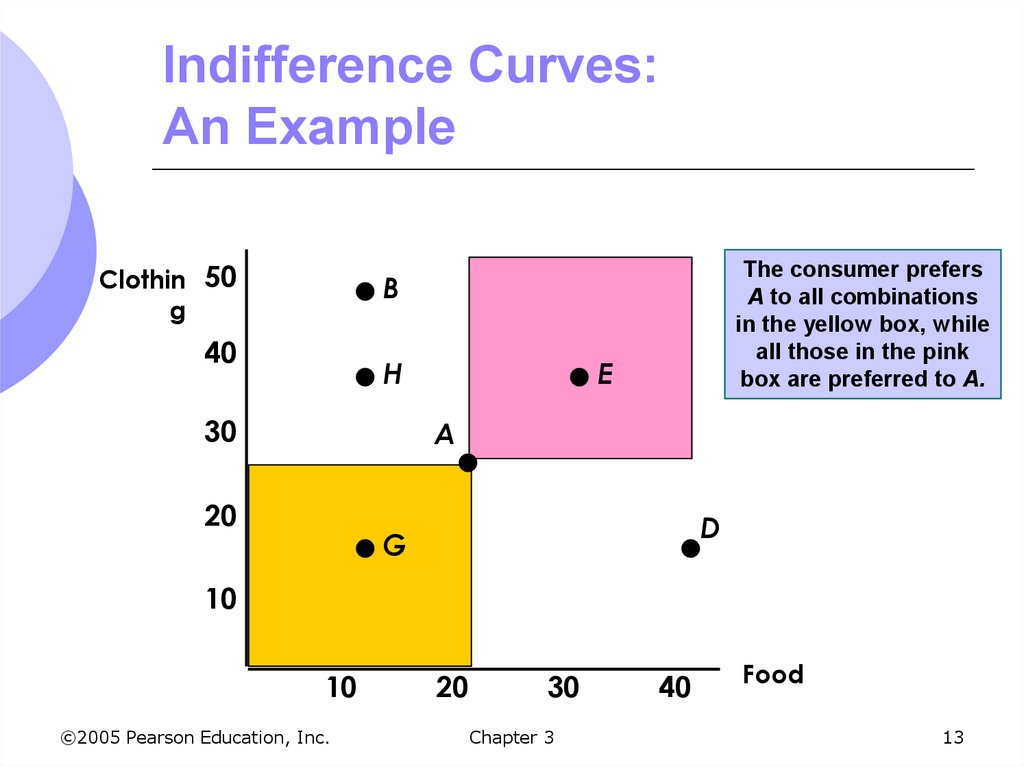

13. Indifference Curves: An Example

Clothin 50g

The consumer prefers

A to all combinations

in the yellow box, while

all those in the pink

box are preferred to A.

B

40

H

30

E

A

20

D

G

10

10

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

20

30

Chapter 3

40

Food

13

14. Indifference Curves: An Example

Points such as B & D have more of onegood but less of another compared to A

Need more information about consumer

ranking

Consumer may decide they are

indifferent between B, A and D

We can then connect those points with an

indifference curve

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

14

15. Indifference Curves: An Example

Clothing

B

50

40

•Indifferent

between points

B, A, & D

•E is preferred

to points on U1

•Points on U1

are preferred to

H&G

H

E

A

30

D

20

U1

G

10

10

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

20

30

Chapter 3

40

Food

15

16. Indifference Curves

Any market basket lying northeast of anindifference curve is preferred to any

market basket that lies on the

indifference curve

Points on the curve are preferred to

points southwest of the curve

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

16

17. Indifference Curves

Indifference curves slope downward tothe right

If they sloped upward, they would violate the

assumption that more is preferred to less

Some points that had more of both goods would

be indifferent to a basket with less of both goods

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

17

18. Indifference Curves

To describe preferences for allcombinations of goods/services, we have

a set of indifference curves – an

indifference map

Each indifference curve in the map shows

the market baskets among which the person

is indifferent

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

18

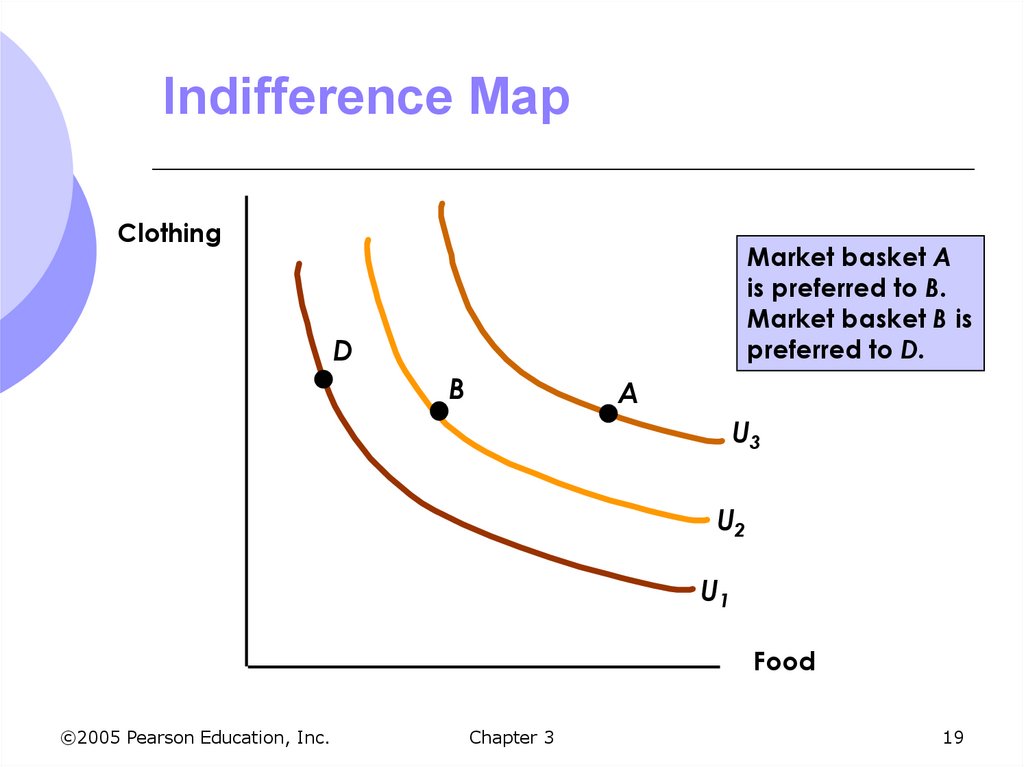

19. Indifference Map

ClothingMarket basket A

is preferred to B.

Market basket B is

preferred to D.

D

B

A

U3

U2

U1

Food

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

19

20. Indifference Maps

Indifference maps give more informationabout shapes of indifference curves

Indifference curves cannot cross

Violates assumption that more is better

Why? What if we assume they can cross?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

20

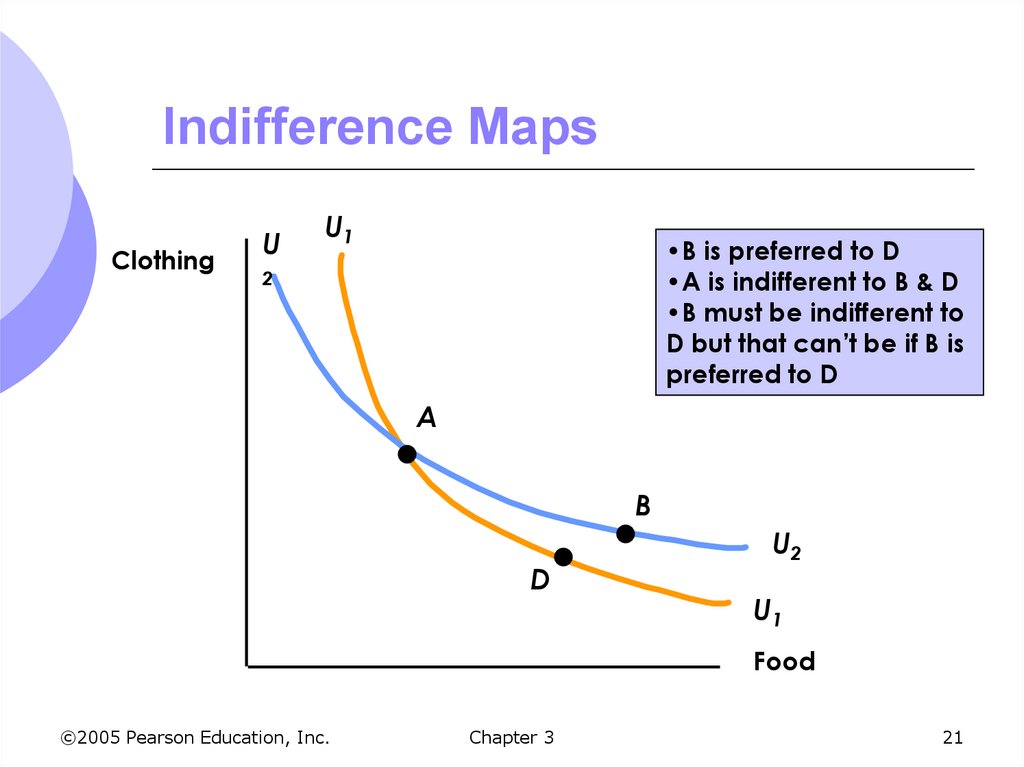

21. Indifference Maps

ClothingU

U1

•B is preferred to D

•A is indifferent to B & D

•B must be indifferent to

D but that can’t be if B is

preferred to D

2

A

B

D

U2

U1

Food

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

21

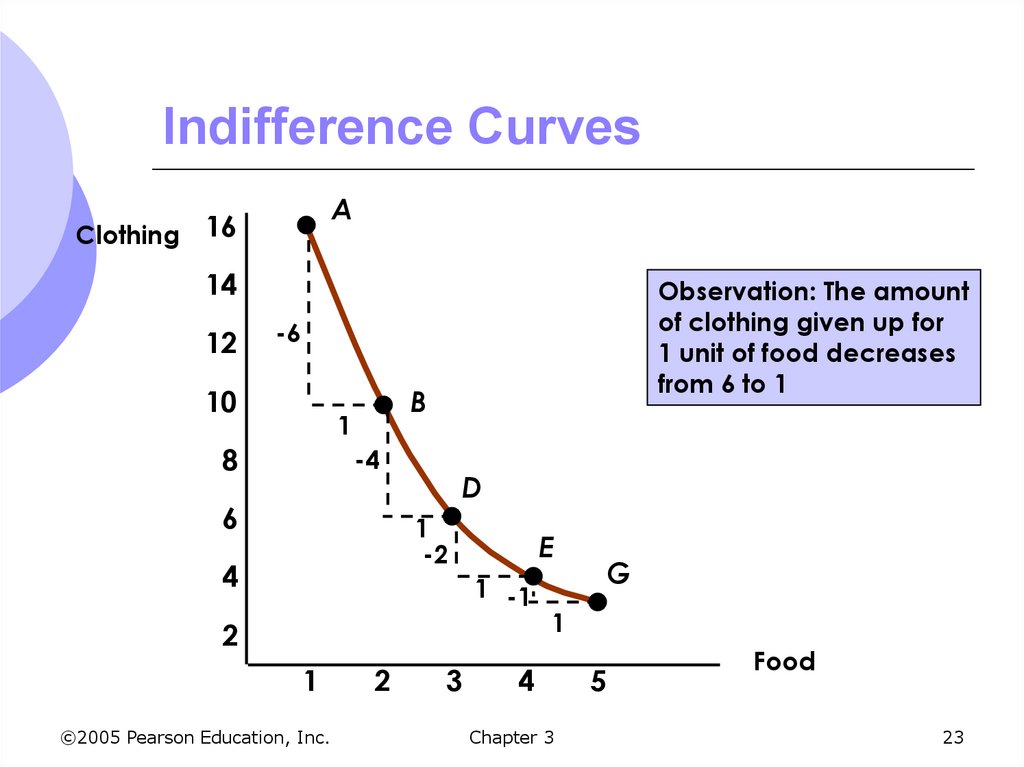

22. Indifference Curves

The shapes of indifference curvesdescribe how a consumer is willing to

substitute one good for another

A to B, give up 6 clothing to get 1 food

D to E, give up 2 clothing to get 1 food

The more clothing and less food a person

has, the more clothing they will give up to

get more food

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

22

23. Indifference Curves

AClothing 16

14

12

Observation: The amount

of clothing given up for

1 unit of food decreases

from 6 to 1

-6

10

B

1

8

-4

6

D

1

-2

4

E

1 -1

2

1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

2

3

G

1

4

Chapter 3

5

Food

23

24. Indifference Curves

We measure how a person trades onegood for another using the marginal rate

of substitution (MRS)

It quantifies the amount of one good a

consumer will give up to obtain more of

another good

It is measured by the slope of the

indifference curve

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

24

25. Marginal Rate of Substitution

AClothing 16

14

12

MRS C

MRS = 6

F

-6

10

B

1

8

-4

6

D

1

-2

4

MRS = 2

E

1 -1

2

1

1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

2

3

4

Chapter 3

5

G

Food

25

26. Marginal Rate of Substitution

Indifference curves are convexAs more of one good is consumed, a

consumer would prefer to give up fewer units

of a second good to get additional units of

the first one

Consumers generally prefer a balanced

market basket

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

26

27. Marginal Rate of Substitution

The MRS decreases as we move downthe indifference curve

Along an indifference curve there is a

diminishing marginal rate of substitution.

The MRS went from 6 to 4 to 1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

27

28. Marginal Rate of Substitution

Indifference curves with different shapesimply a different willingness to substitute

Two polar cases are of interest

Perfect substitutes

Perfect complements

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

28

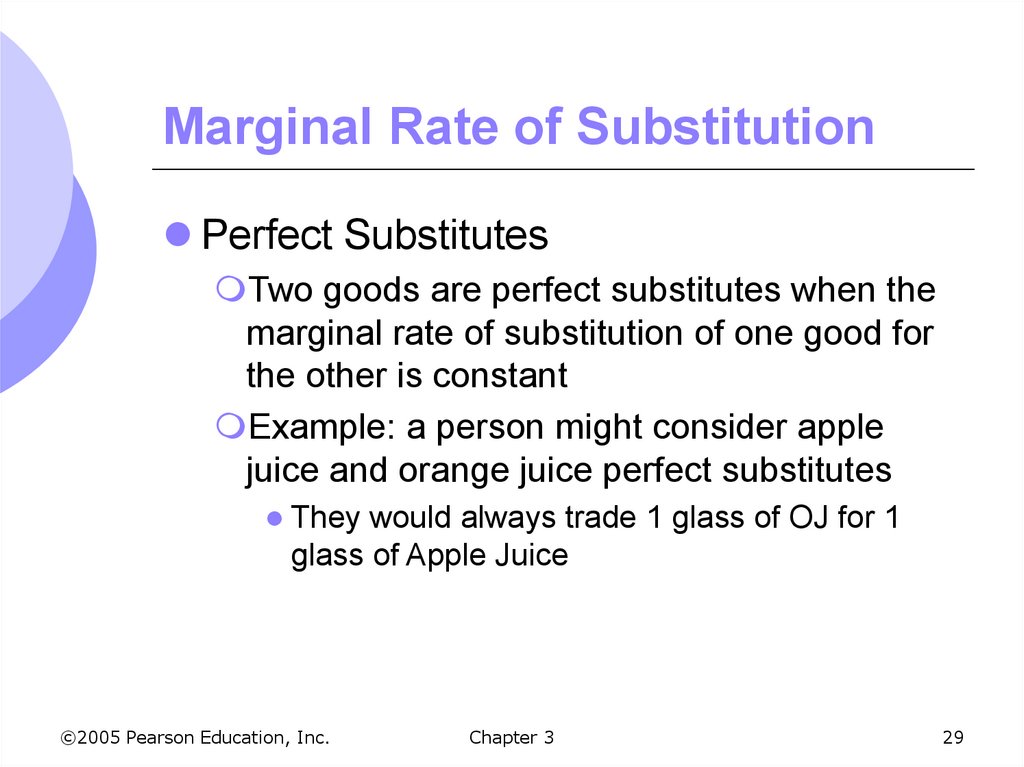

29. Marginal Rate of Substitution

Perfect SubstitutesTwo goods are perfect substitutes when the

marginal rate of substitution of one good for

the other is constant

Example: a person might consider apple

juice and orange juice perfect substitutes

They would always trade 1 glass of OJ for 1

glass of Apple Juice

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

29

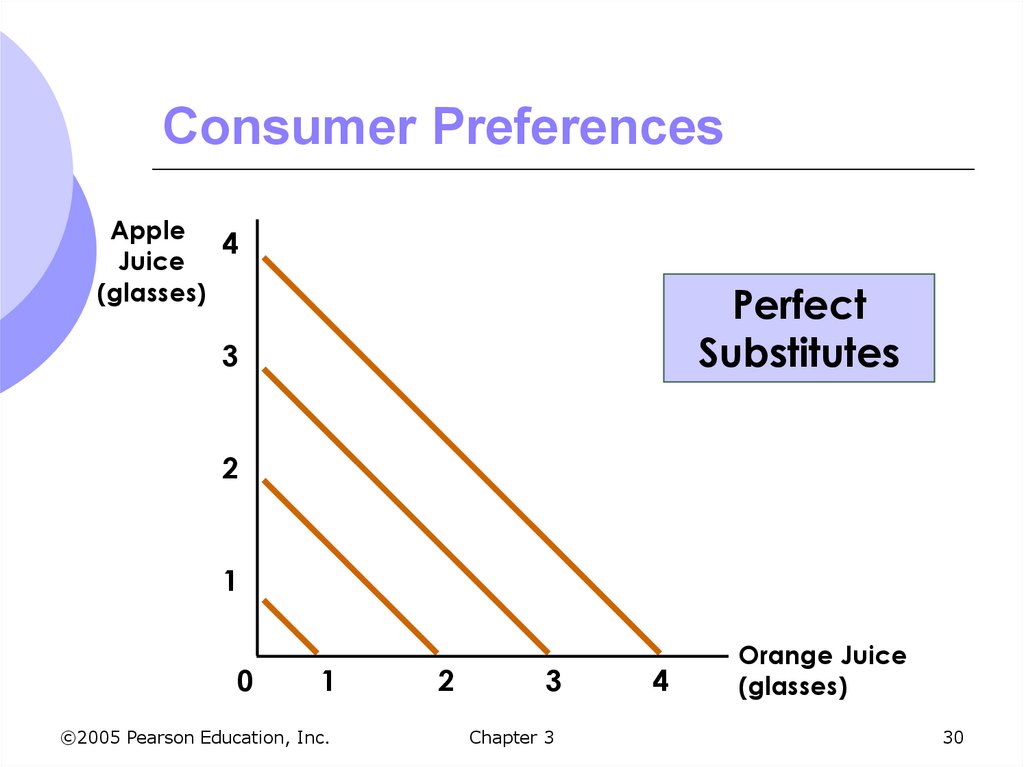

30. Consumer Preferences

Apple4

Juice

(glasses)

Perfect

Substitutes

3

2

1

0

1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

2

3

Chapter 3

4

Orange Juice

(glasses)

30

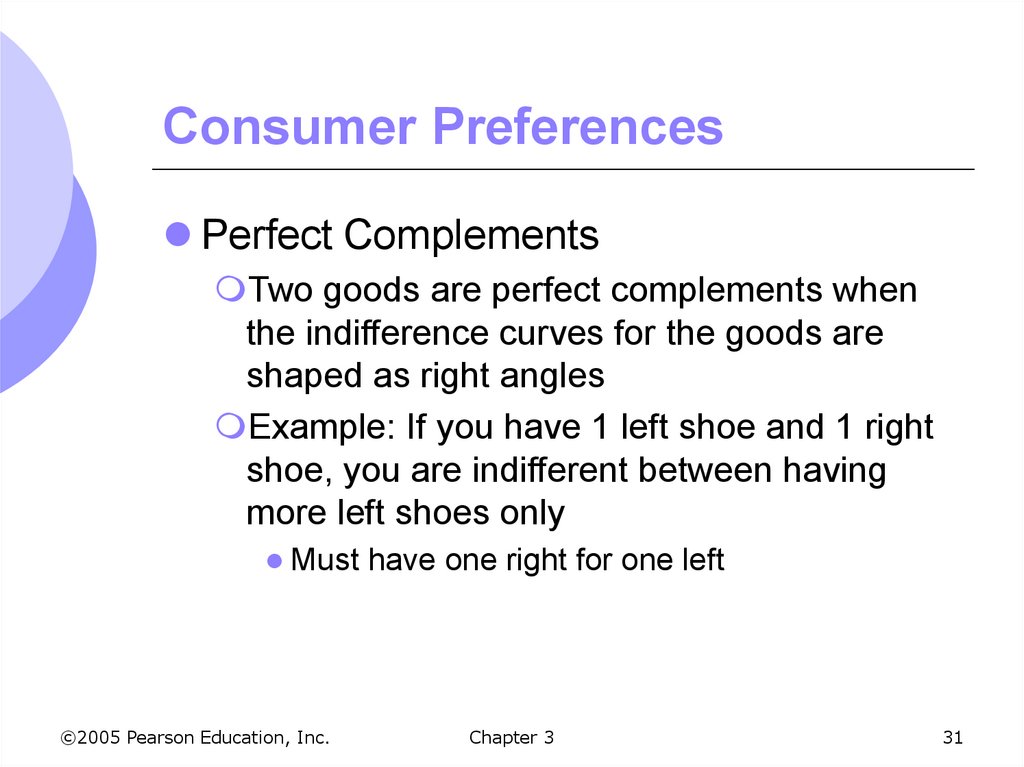

31. Consumer Preferences

Perfect ComplementsTwo goods are perfect complements when

the indifference curves for the goods are

shaped as right angles

Example: If you have 1 left shoe and 1 right

shoe, you are indifferent between having

more left shoes only

Must have one right for one left

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

31

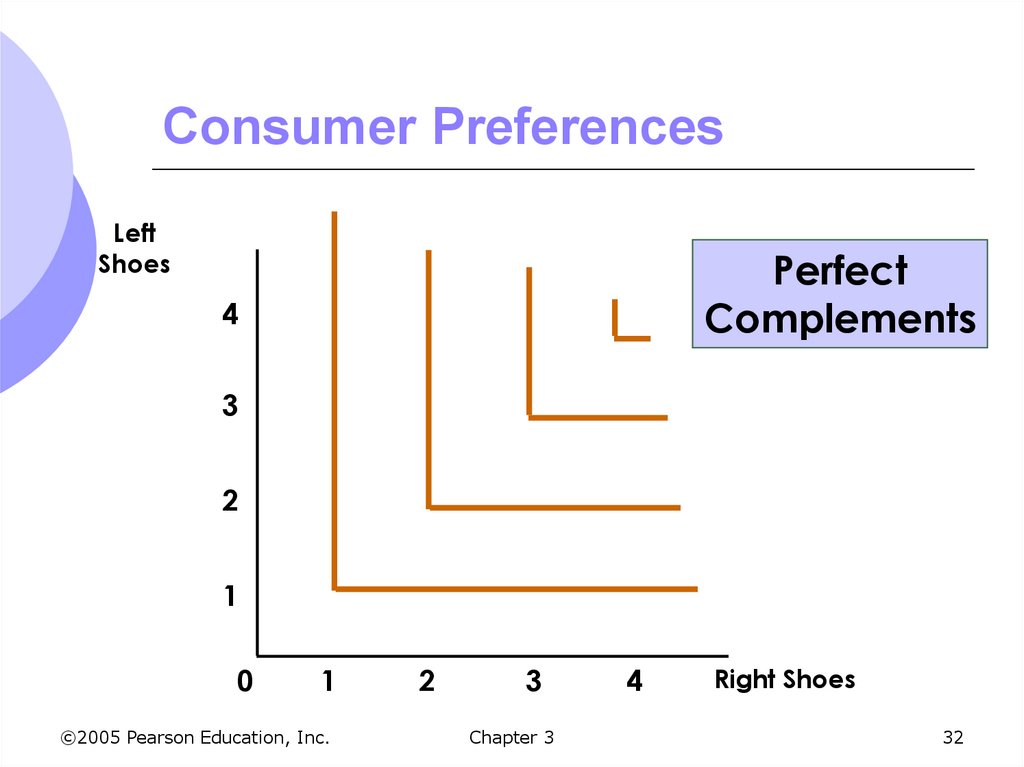

32. Consumer Preferences

LeftShoes

Perfect

Complements

4

3

2

1

0

1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

2

3

Chapter 3

4

Right Shoes

32

33. Consumer Preferences

We have assumed all our commoditiesare “goods”

There are commodities we don’t want

more of - bads

Things for which less is preferred to more

Examples

Air pollution

Asbestos

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

33

34. Consumer Preferences

How do we account for bads in ourpreference analysis?

We redefine the commodity

Clean air

Pollution reduction

Asbestos removal

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

34

35. Consumer Preferences: An Application

In designing new cars, automobileexecutives must determine how much

time and money to invest in restyling

versus increased performance

Higher demand for car with better styling and

performance

Both cost more to improve

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

35

36. Consumer Preferences: An Application

An analysis of consumer preferenceswould help to determine where to spend

more on change: performance or styling

Some consumers will prefer better styling

and some will prefer better performance

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

36

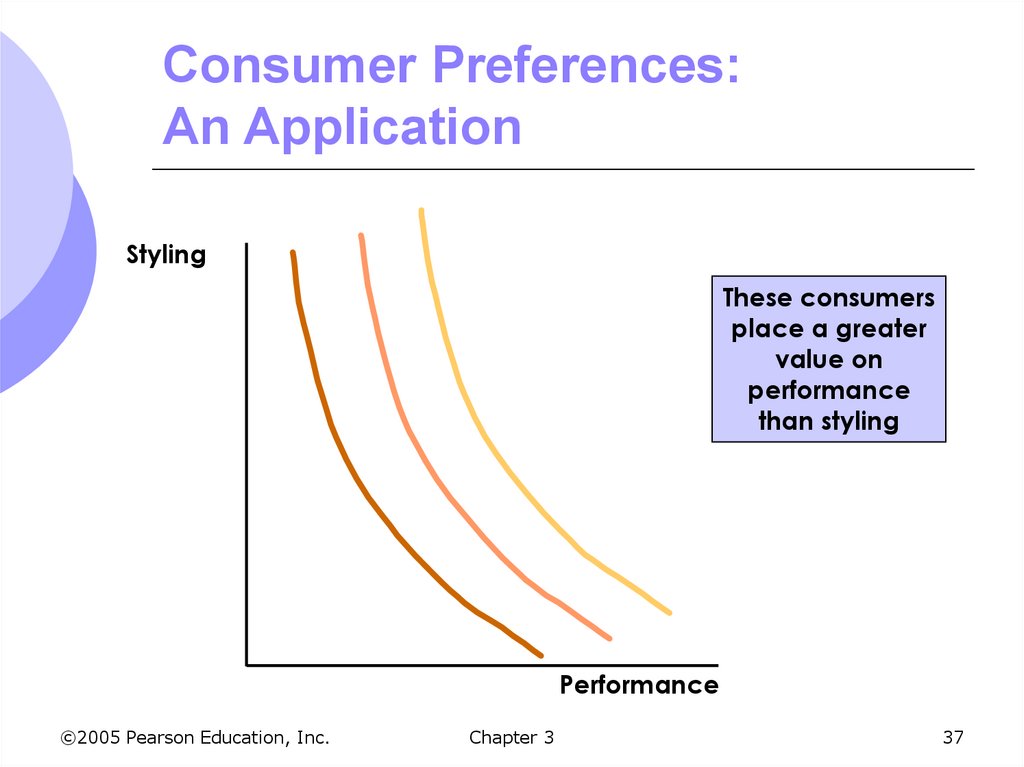

37. Consumer Preferences: An Application

StylingThese consumers

place a greater

value on

performance

than styling

Performance

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

37

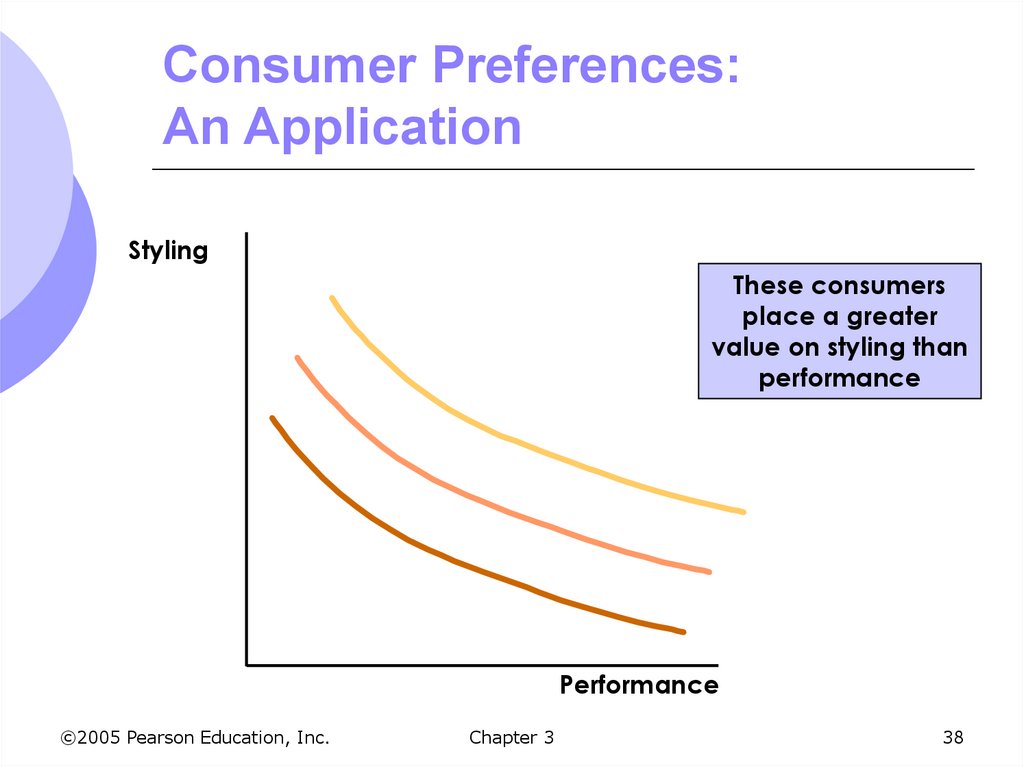

38. Consumer Preferences: An Application

StylingThese consumers

place a greater

value on styling than

performance

Performance

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

38

39. Consumer Preferences: An Application

Knowing which group dominates themarket will help decide where

redesigning dollars should go

A recent study in the US shows that over

the past two decades, most consumers

have preferred styling over performance

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

39

40. Consumer Preferences

The theory of consumer behavior doesnot required assigning a numerical value

to the level of satisfaction

Although ranking of market baskets is

good, sometimes numerical value is

useful

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

40

41. Consumer Preferences

UtilityA numerical score representing the

satisfaction that a consumer gets from a

given market basket

If buying 3 copies of Microeconomics makes

you happier than buying one shirt, then we

say that the books give you more utility than

the shirt

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

41

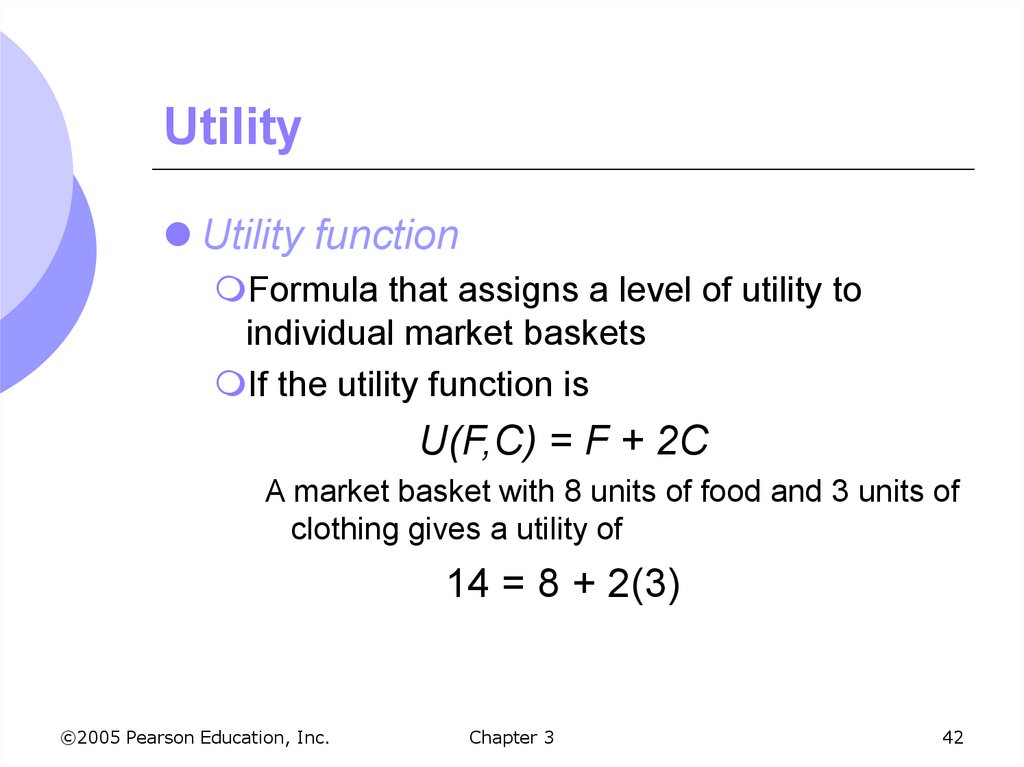

42. Utility

Utility functionFormula that assigns a level of utility to

individual market baskets

If the utility function is

U(F,C) = F + 2C

A market basket with 8 units of food and 3 units of

clothing gives a utility of

14 = 8 + 2(3)

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

42

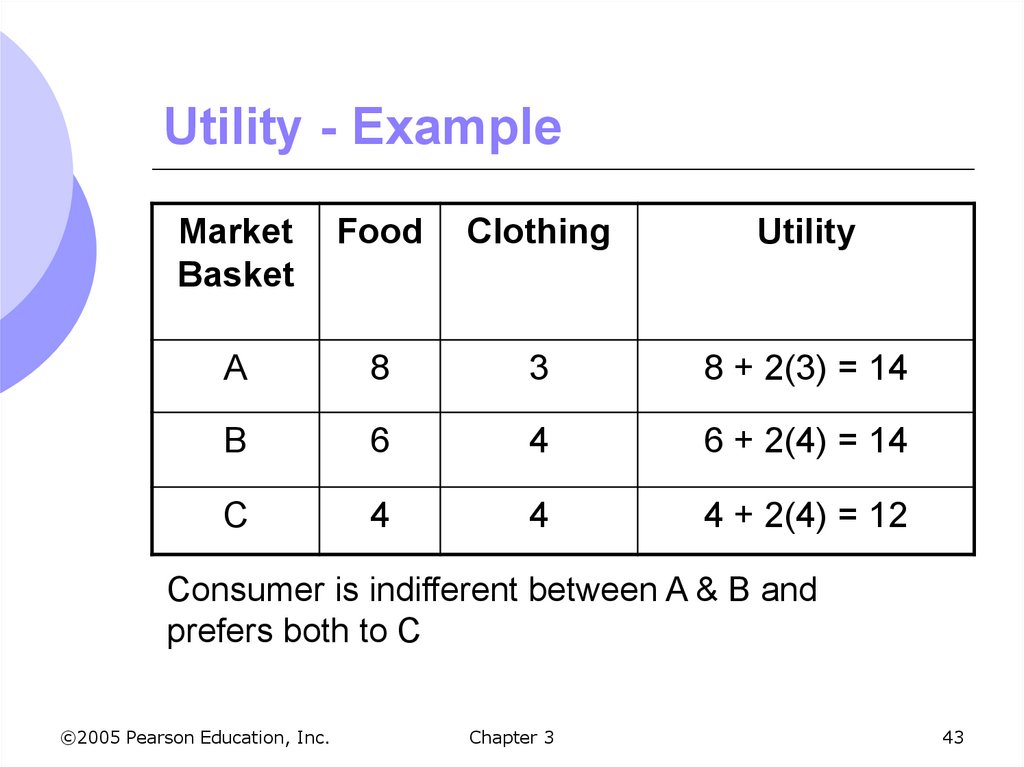

43. Utility - Example

MarketBasket

Food

Clothing

Utility

A

8

3

8 + 2(3) = 14

B

6

4

6 + 2(4) = 14

C

4

4

4 + 2(4) = 12

Consumer is indifferent between A & B and

prefers both to C

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

43

44. Utility - Example

Baskets for each level of utility can beplotted to get an indifference curve

To find the indifference curve for a utility of

14, we can change the combinations of food

and clothing that give us a utility of 14

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

44

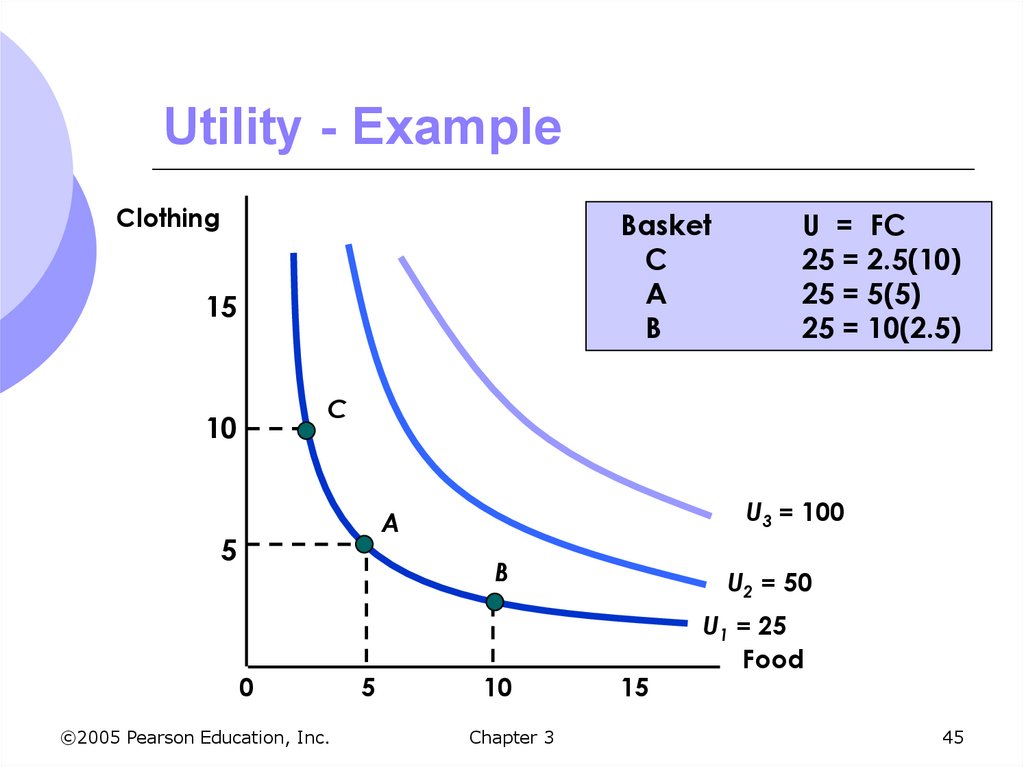

45. Utility - Example

ClothingBasket

C

A

B

15

U = FC

25 = 2.5(10)

25 = 5(5)

25 = 10(2.5)

C

10

U3 = 100

A

5

B

0

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

5

10

Chapter 3

U2 = 50

15

U1 = 25

Food

45

46. Utility

Although we numerically rank basketsand indifference curves, numbers are

ONLY for ranking

A utility of 4 is not necessarily twice as

good as a utility of 2

There are two types of rankings

Ordinal ranking

Cardinal ranking

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

46

47. Utility

Ordinal Utility FunctionPlaces market baskets in the order of most

preferred to least preferred, but it does not

indicate how much one market basket is

preferred to another

Cardinal Utility Function

Utility function describing the extent to which

one market basket is preferred to another

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

47

48. Utility

The actual unit of measurement for utilityis not important

An ordinal ranking is sufficient to explain

how most individual decisions are made

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

48

49. Budget Constraints

Preferences do not explain all ofconsumer behavior

Budget constraints also limit an

individual’s ability to consume in light of

the prices they must pay for various

goods and services

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

49

50. Budget Constraints

The Budget LineIndicates all combinations of two

commodities for which total money spent

equals total income

We assume only 2 goods are consumed, so

we do not consider savings

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

50

51. The Budget Line

Let F equal the amount of foodpurchased, and C is the amount of

clothing

Price of food = PF and price of

clothing = PC

Then PFF is the amount of money spent

on food, and PCC is the amount of money

spent on clothing

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

51

52. The Budget Line

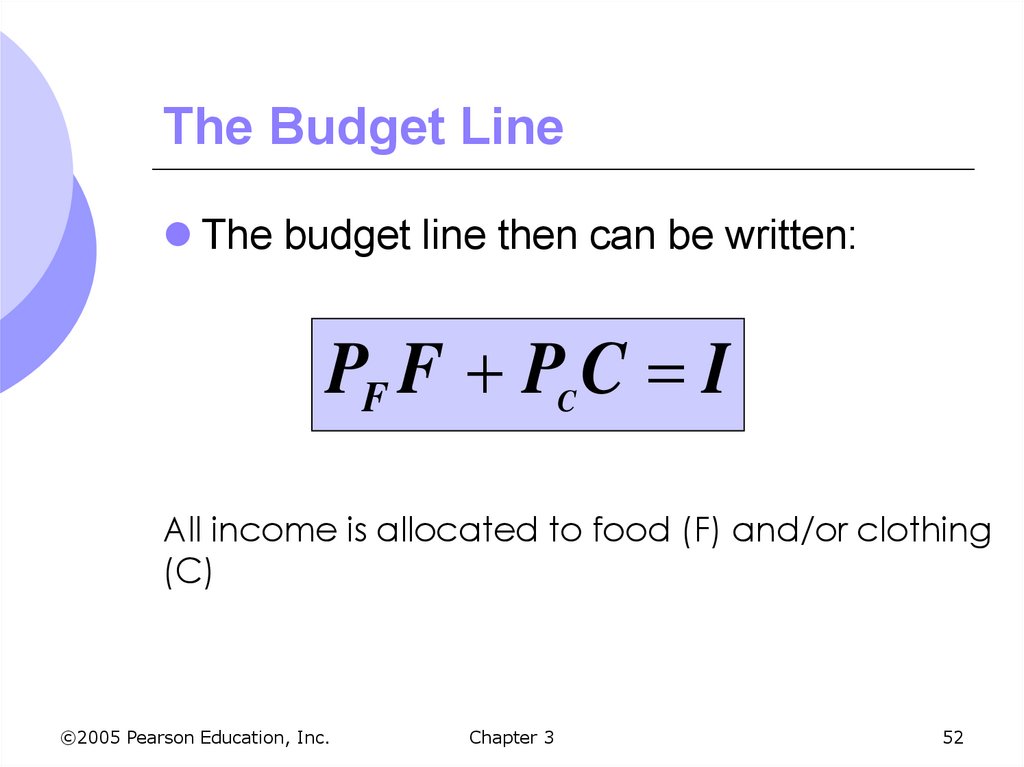

The budget line then can be written:PF F PC C I

All income is allocated to food (F) and/or clothing

(C)

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

52

53. The Budget Line

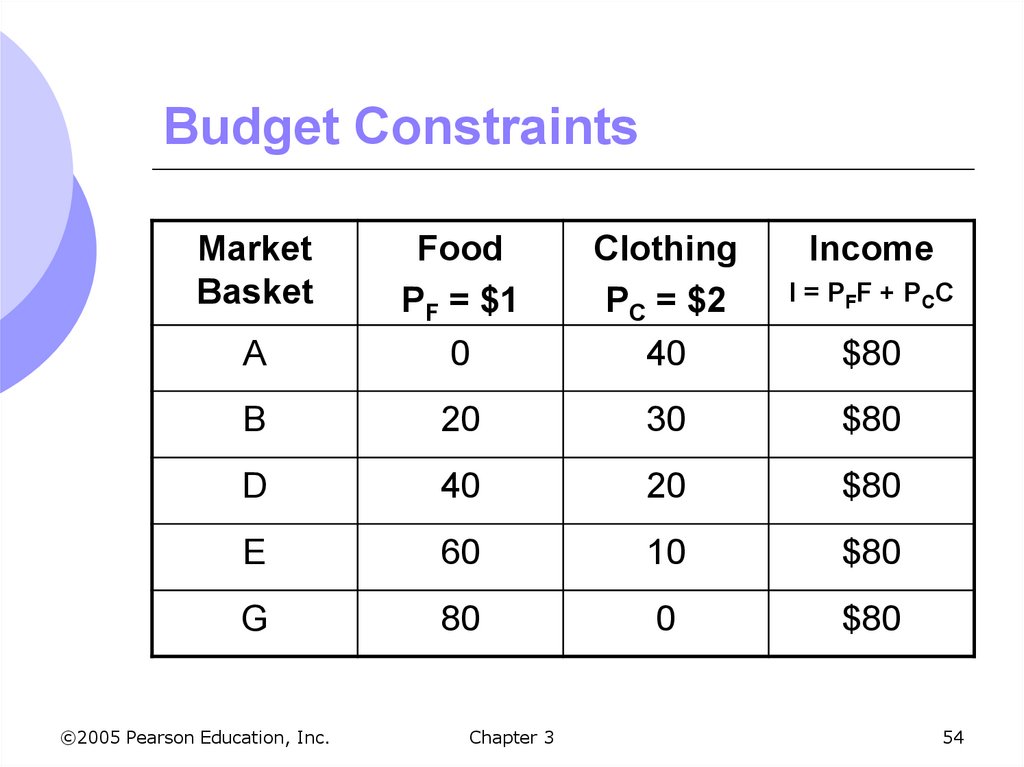

Different choices of food and clothing canbe calculated that use all income

These choices can be graphed as the budget

line

Example:

Assume income of $80/week, PF = $1 and PC

= $2

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

53

54. Budget Constraints

MarketBasket

Clothing

PC = $2

40

I = PFF + PCC

A

Food

PF = $1

0

B

20

30

$80

D

40

20

$80

E

60

10

$80

G

80

0

$80

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

Income

$80

54

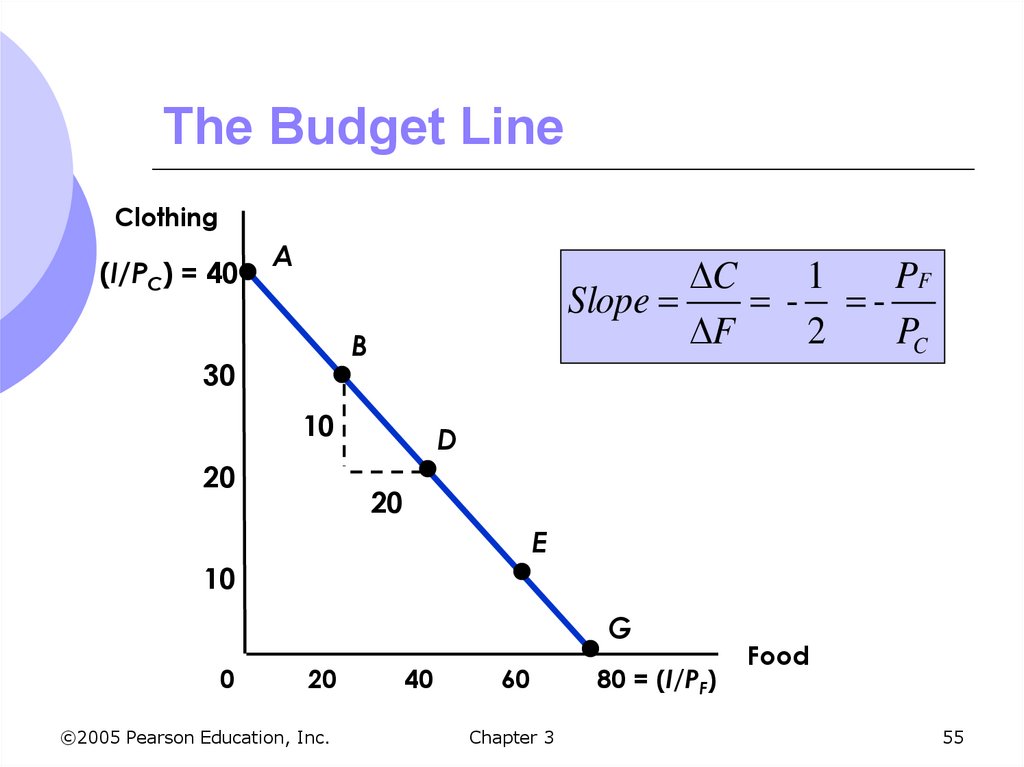

55. The Budget Line

Clothing(I/PC) = 40

A

C

1

PF

Slope

- F

2

PC

B

30

10

20

D

20

E

10

G

0

20

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

40

60

Chapter 3

80 = (I/PF)

Food

55

56. The Budget Line

As consumption moves along a budgetline from the intercept, the consumer

spends less on one item and more on the

other

The slope of the line measures the

relative cost of food and clothing

The slope is the negative of the ratio of

the prices of the two goods

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

56

57. The Budget Line

The slope indicates the rate at which thetwo goods can be substituted without

changing the amount of money spent

We can rearrange the budget line

equation to make this more clear

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

57

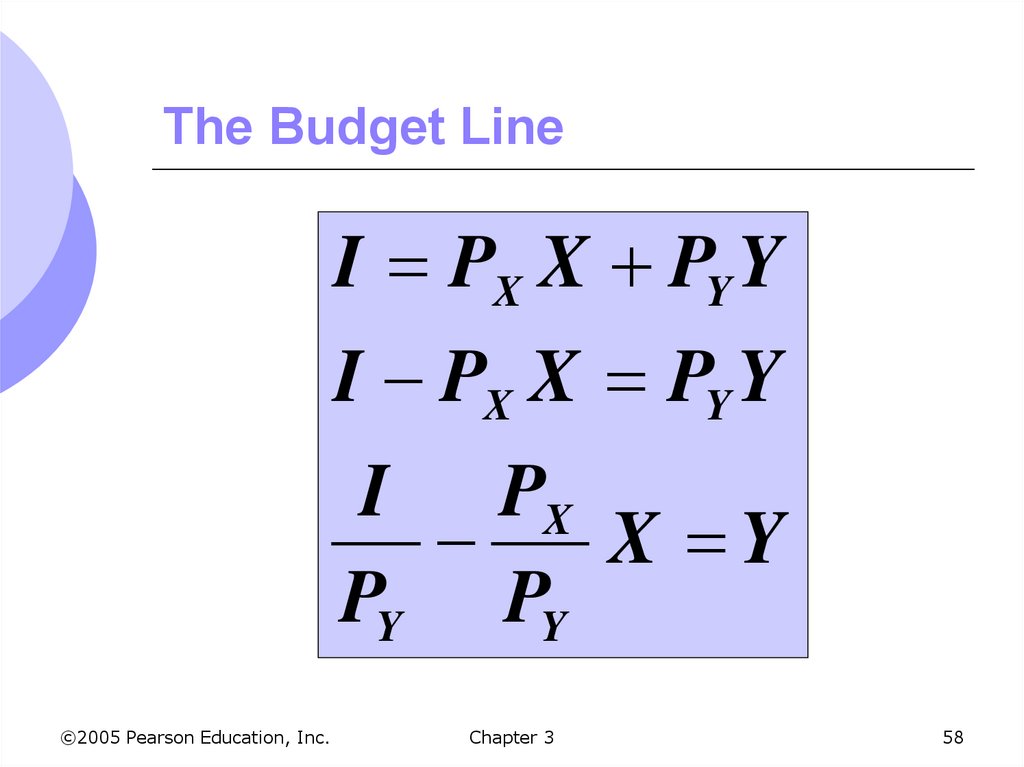

58. The Budget Line

I PX X PY YI PX X PY Y

I PX

X Y

PY PY

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

58

59. Budget Constraints

The Budget LineThe vertical intercept, I/PC, illustrates the

maximum amount of C that can be

purchased with income I

The horizontal intercept, I/PF, illustrates the

maximum amount of F that can be

purchased with income I

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

59

60. The Budget Line

As we know, income and prices canchange

As incomes and prices change, there are

changes in budget lines

We can show the effects of these

changes on budget lines and consumer

choices

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

60

61. The Budget Line - Changes

The Effects of Changes in IncomeAn increase in income causes the budget

line to shift outward, parallel to the original

line (holding prices constant).

Can buy more of both goods with more

income

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

61

62. The Budget Line - Changes

The Effects of Changes in IncomeA decrease in income causes the budget line

to shift inward, parallel to the original line

(holding prices constant)

Can buy less of both goods with less income

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

62

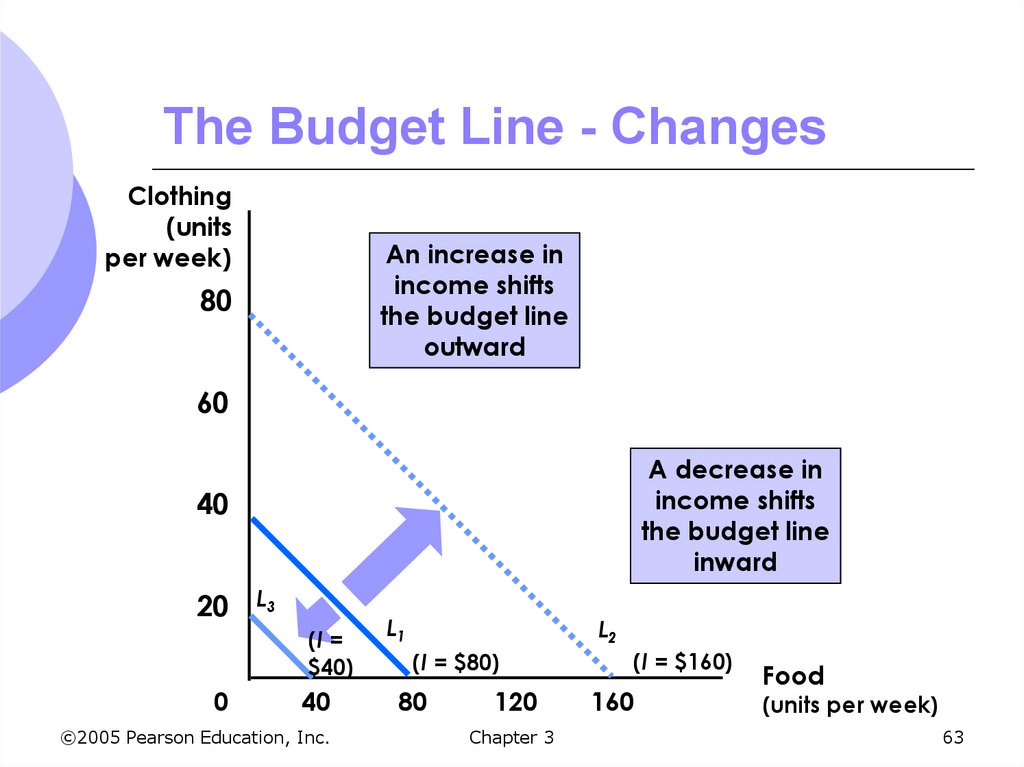

63. The Budget Line - Changes

Clothing(units

per week)

An increase in

income shifts

the budget line

outward

80

60

A decrease in

income shifts

the budget line

inward

40

20

0

L3

(I =

$40)

L1

40

80

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

L2

(I = $80)

120

Chapter 3

(I = $160)

160

Food

(units per week)

63

64. The Budget Line - Changes

The Effects of Changes in PricesIf the price of one good increases, the

budget line shifts inward, pivoting from the

other good’s intercept.

If the price of food increases and you buy

only food (x-intercept), then you can’t buy as

much food. The x-intercept shifts in.

If you buy only clothing (y-intercept), you can

buy the same amount. No change in yintercept.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

64

65. The Budget Line - Changes

The Effects of Changes in PricesIf the price of one good decreases, the

budget line shifts outward, pivoting from the

other good’s intercept.

If the price of food decreases and you buy

only food (x-intercept), then you can buy

more food. The x-intercept shifts out.

If you buy only clothing (y-intercept), you can

buy the same amount. No change in yintercept.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

65

66. The Budget Line - Changes

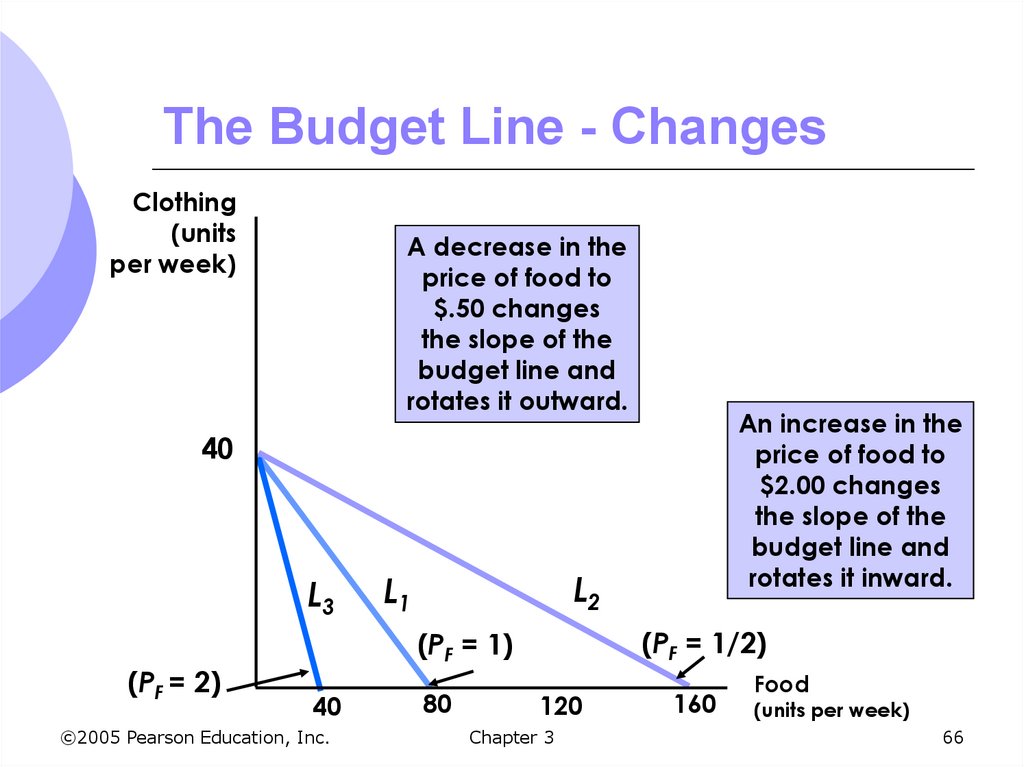

Clothing(units

per week)

A decrease in the

price of food to

$.50 changes

the slope of the

budget line and

rotates it outward.

An increase in the

price of food to

$2.00 changes

the slope of the

budget line and

rotates it inward.

40

L3

(PF = 2)

L2

L1

(PF = 1/2)

(PF = 1)

40

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

80

120

Chapter 3

160

Food

(units per week)

66

67. The Budget Line - Changes

The Effects of Changes in PricesIf the two goods increase in price, but the

ratio of the two prices is unchanged, the

slope will not change

However, the budget line will shift inward

parallel to the original budget line

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

67

68. The Budget Line - Changes

The Effects of Changes in PricesIf the two goods decrease in price, but the

ratio of the two prices is unchanged, the

slope will not change

However, the budget line will shift outward

parallel to the original budget line

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

68

69. Consumer Choice

Given preferences and budgetconstraints, how do consumers choose

what to buy?

Consumers choose a combination of

goods that will maximize their

satisfaction, given the limited budget

available to them

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

69

70. Consumer Choice

The maximizing market basket mustsatisfy two conditions:

1. It must be located on the budget line

They spend all their income – more is better

2. It must give the consumer the most

preferred combination of goods and

services

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

70

71. Consumer Choice

Graphically, we can see differentindifference curves of a consumer

choosing between clothing and food

Remember that U3 > U2 > U1 for our

indifference curves

Consumer wants to choose highest utility

within their budget

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

71

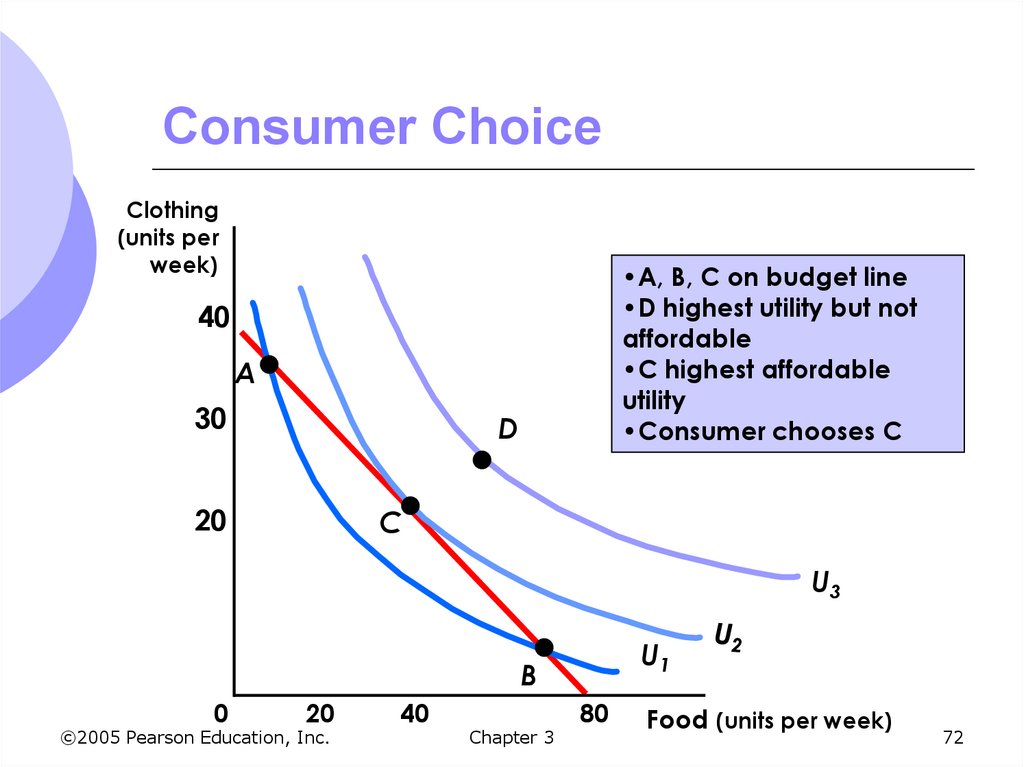

72. Consumer Choice

Clothing(units per

week)

•A, B, C on budget line

•D highest utility but not

affordable

•C highest affordable

utility

•Consumer chooses C

40

A

30

D

20

C

U3

U1

B

0

20

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

40

Chapter 3

80

Food (units per week)

72

73. Consumer Choice

Consumer will choose highestindifference curve on budget line

In previous graph, point C is where the

indifference curve is just tangent to the

budget line

Slope of the budget line equals the slope

of the indifference curve at this point

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

73

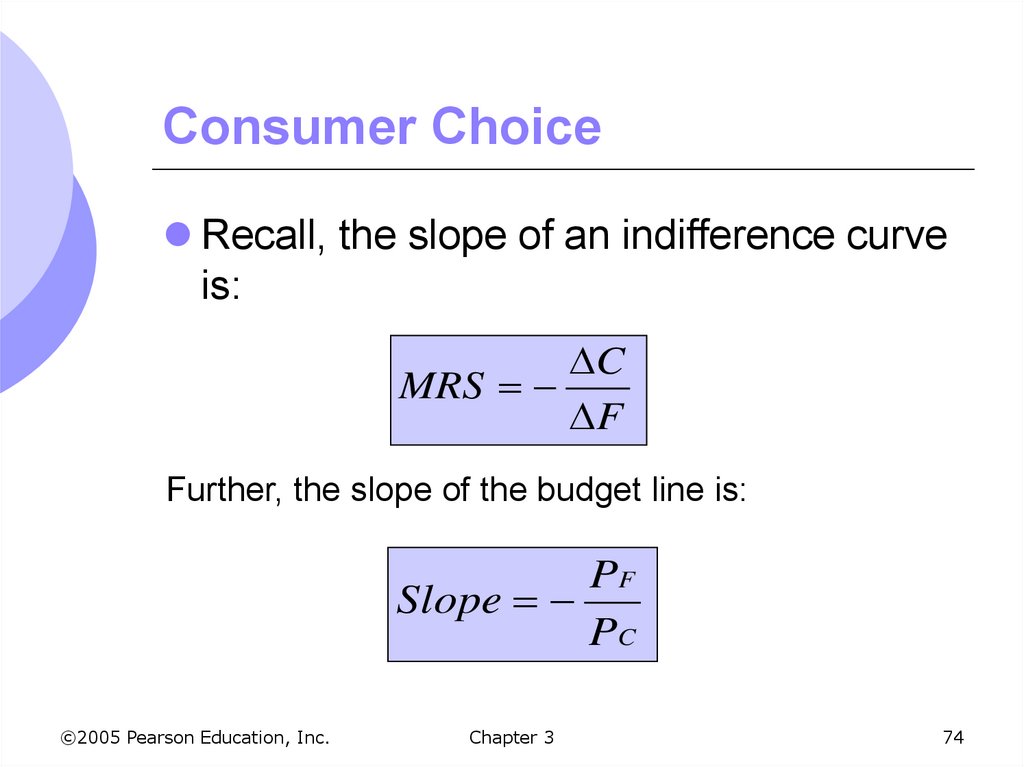

74. Consumer Choice

Recall, the slope of an indifference curveis:

C

MRS

F

Further, the slope of the budget line is:

PF

Slope

PC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

74

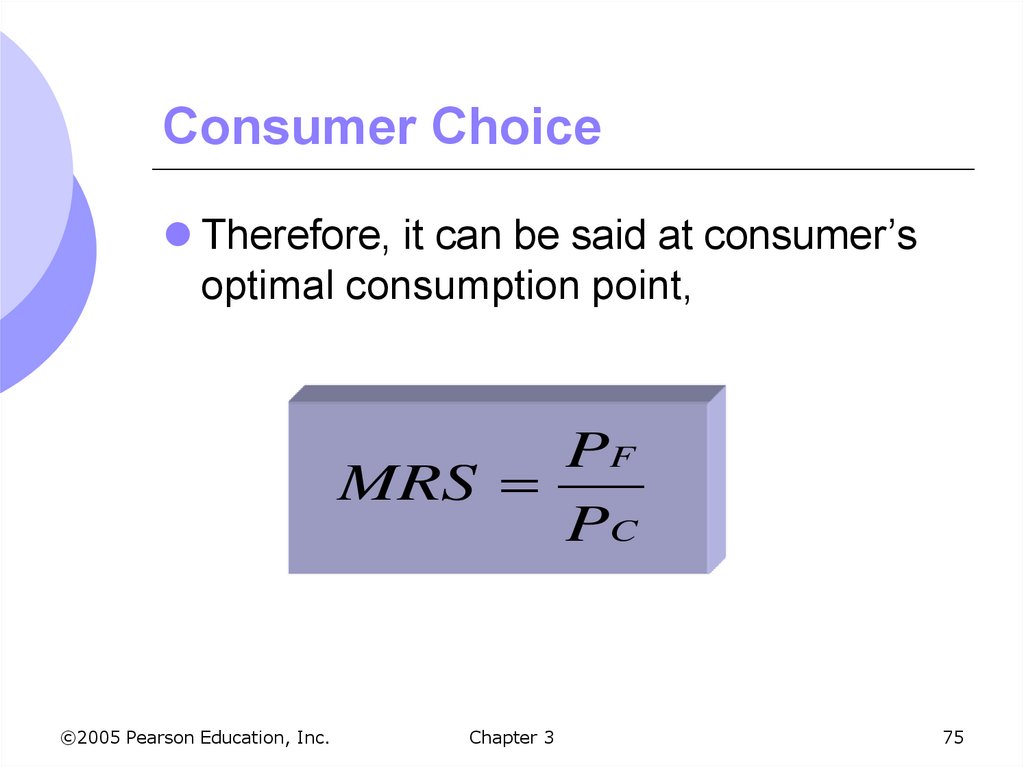

75. Consumer Choice

Therefore, it can be said at consumer’soptimal consumption point,

PF

MRS

PC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

75

76. Consumer Choice

It can be said that satisfaction ismaximized when marginal rate of

substitution (of F and C) is equal to the

ratio of the prices (of F and C)

Note this is ONLY true at the optimal

consumption point

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

76

77. Consumer Choice

Optimal consumption point is wheremarginal benefits equal marginal costs

MB = MRS = benefit associated with

consumption of 1 more unit of food

MC = cost of additional unit of food

1 unit food = ½ unit clothing

PF/PC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

77

78. Consumer Choice

If MRS ≠ PF/PC then individuals canreallocate basket to increase utility

If MRS > PF/PC

Will increase food and decrease clothing until

MRS = PF/PC

If MRS < PF/PC

Will increase clothing and decrease food until

MRS = PF/PC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

78

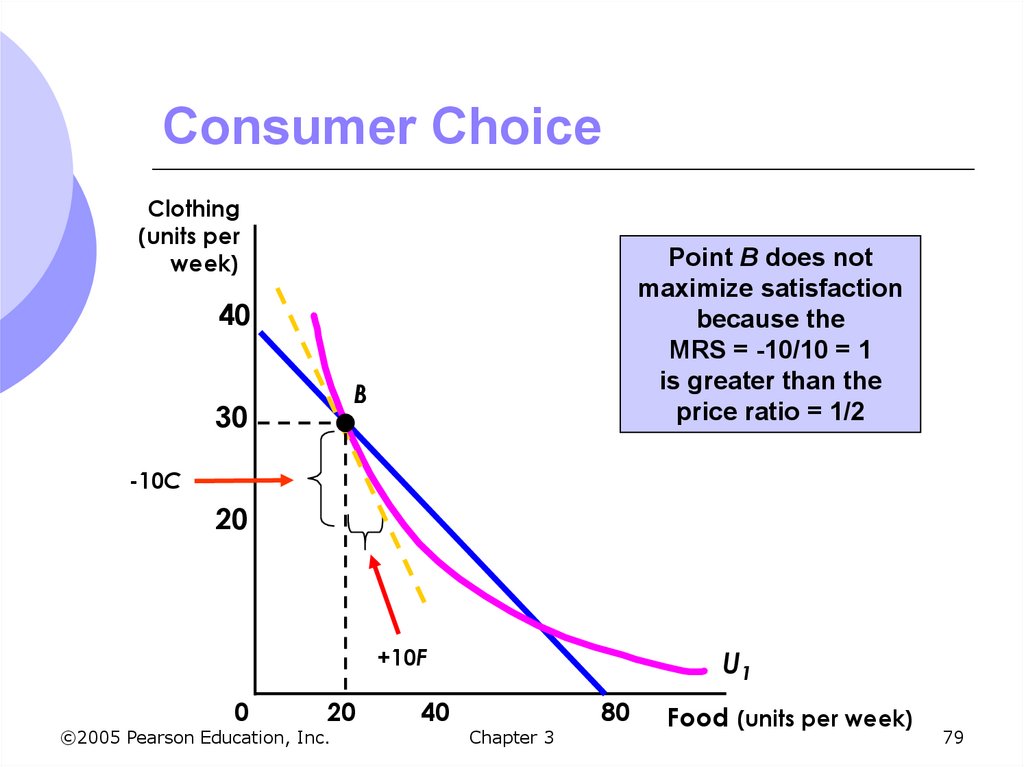

79. Consumer Choice

Clothing(units per

week)

Point B does not

maximize satisfaction

because the

MRS = -10/10 = 1

is greater than the

price ratio = 1/2

40

B

30

-10C

20

+10F

0

20

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

40

U1

Chapter 3

80

Food (units per week)

79

80. Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited

Consider two groups of consumers, eachwishing to spend $10,000 on the styling

and performance of a car

Each group has different preferences

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

80

81. Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited

By finding the point of tangency betweena group’s indifference curve and the

budget constraint, auto companies can

see how much consumers value each

attribute

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

81

82. Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited

Styling$10,000

These consumers

want performance

worth $7000 and styling

worth $3000

$3,000

$7,000

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

$10,000 Performance

82

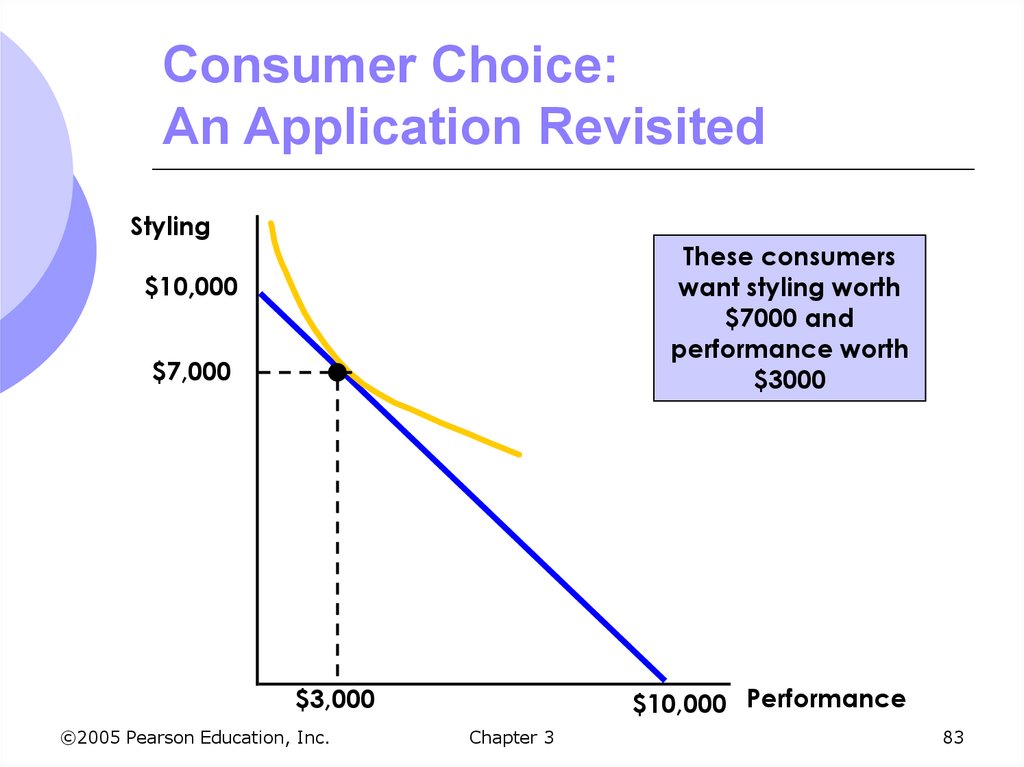

83. Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited

StylingThese consumers

want styling worth

$7000 and

performance worth

$3000

$10,000

$7,000

$10,000 Performance

$3,000

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

83

84. Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited

Once a company knows preferences, itcan design a production and marketing

plan

Company can then make a sensible

strategic business decision on how to

allocate performance and styling on new

cars

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

84

85. Consumer Choice

A corner solution exists if a consumerbuys in extremes, and buys all of one

category of good and none of another

MRS is not necessarily equal to PA/PB

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

85

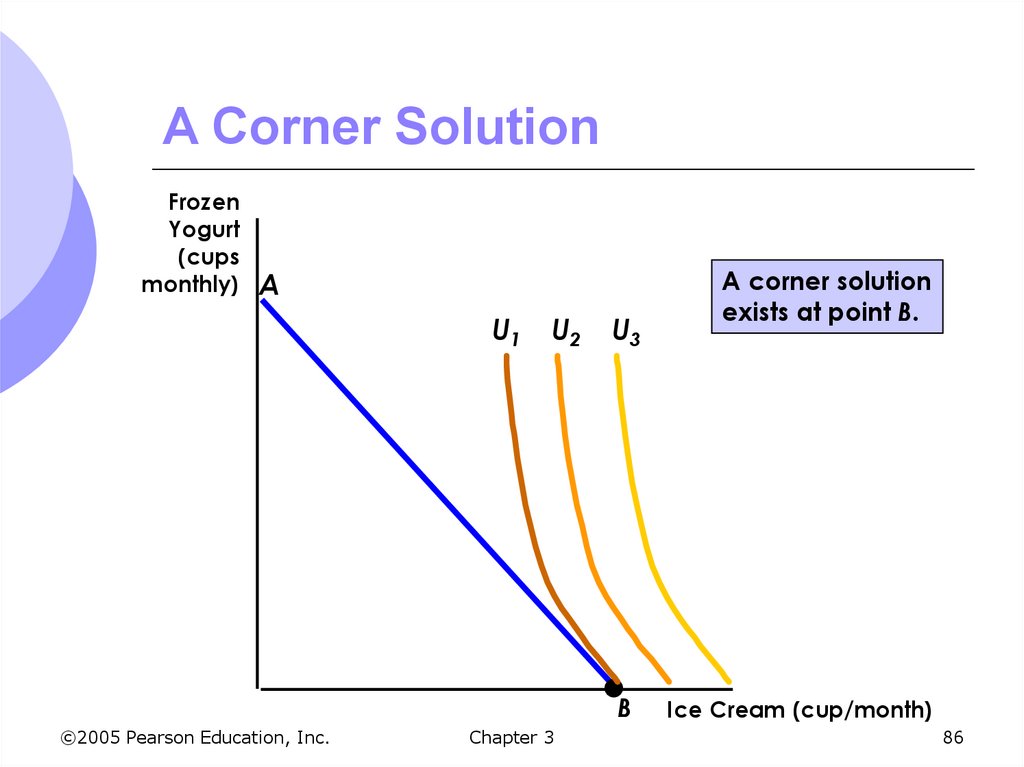

86. A Corner Solution

FrozenYogurt

(cups

monthly)

A

U1

U2

U3

B

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

A corner solution

exists at point B.

Ice Cream (cup/month)

86

87. A Corner Solution

At point B, the MRS of ice cream for frozenyogurt is greater than the slope of the budget

line

If the consumer could give up more frozen

yogurt for ice cream, he would do so

However, there is no more frozen yogurt to give

up

Opposite is true if corner solution was at point A

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

87

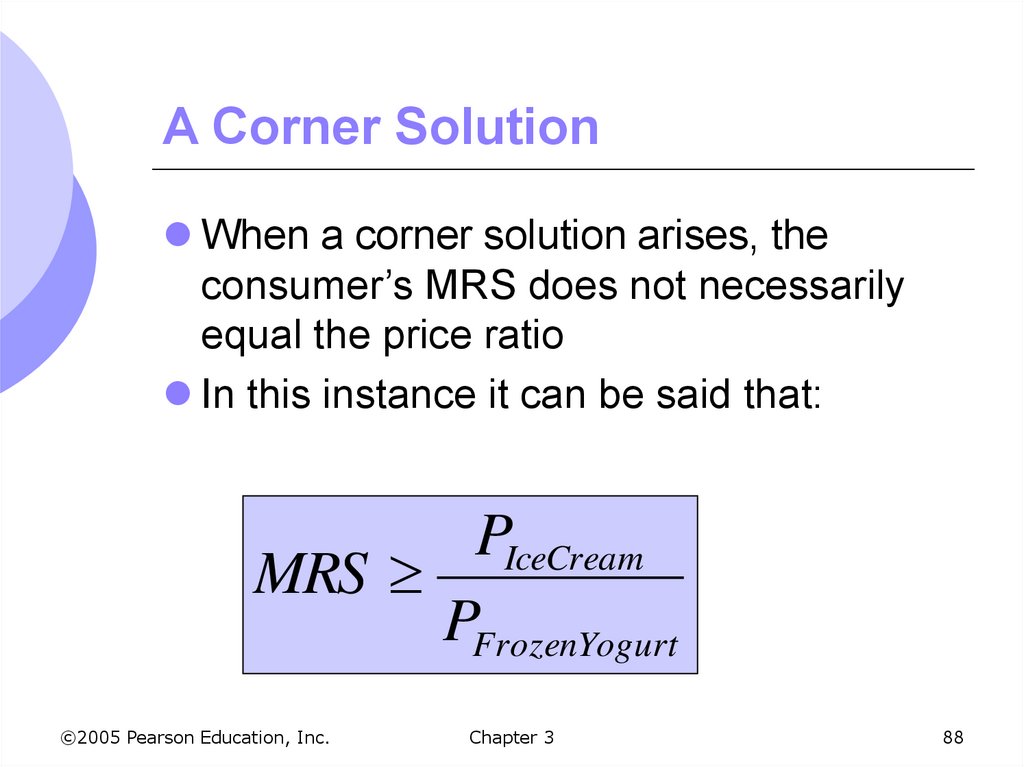

88. A Corner Solution

When a corner solution arises, theconsumer’s MRS does not necessarily

equal the price ratio

In this instance it can be said that:

PIceCream

MRS

PFrozenYogurt

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

88

89. A Corner Solution

If the MRS is, in fact, significantly greaterthan the price ratio, then a small

decrease in the price of frozen yogurt will

not alter the consumer’s market basket

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

89

90. A Corner Solution - Example

Suppose Jane Doe’s parents set up atrust fund for her college education

The money must be used only for

education

Although a welcome gift, an unrestricted

gift might be better

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

90

91. A Corner Solution - Example

Original budget line, PQ, with a marketbasket, A, of education and other goods

Trust fund shifts out the budget line as

long as trust fund, PB, is spent on

education

Jane increases satisfaction, moving to

higher indifference curve, U2

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

91

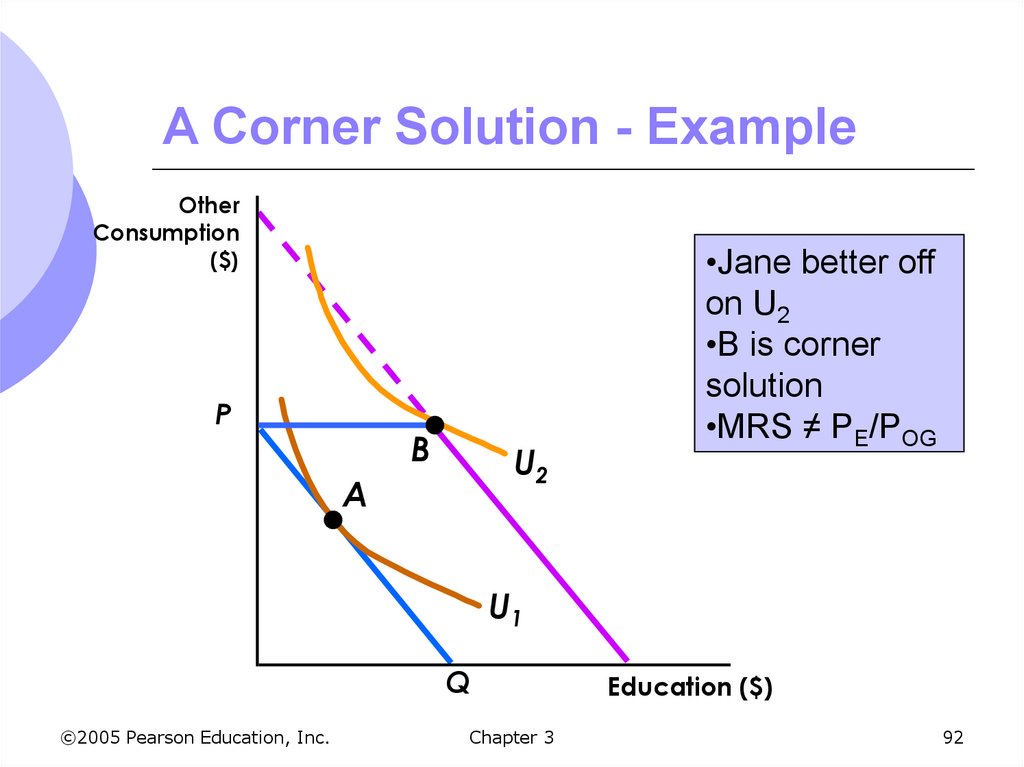

92. A Corner Solution - Example

OtherConsumption

($)

P

B

U2

A

•Jane better off

on U2

•B is corner

solution

•MRS ≠ PE/POG

U1

Q

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

Education ($)

92

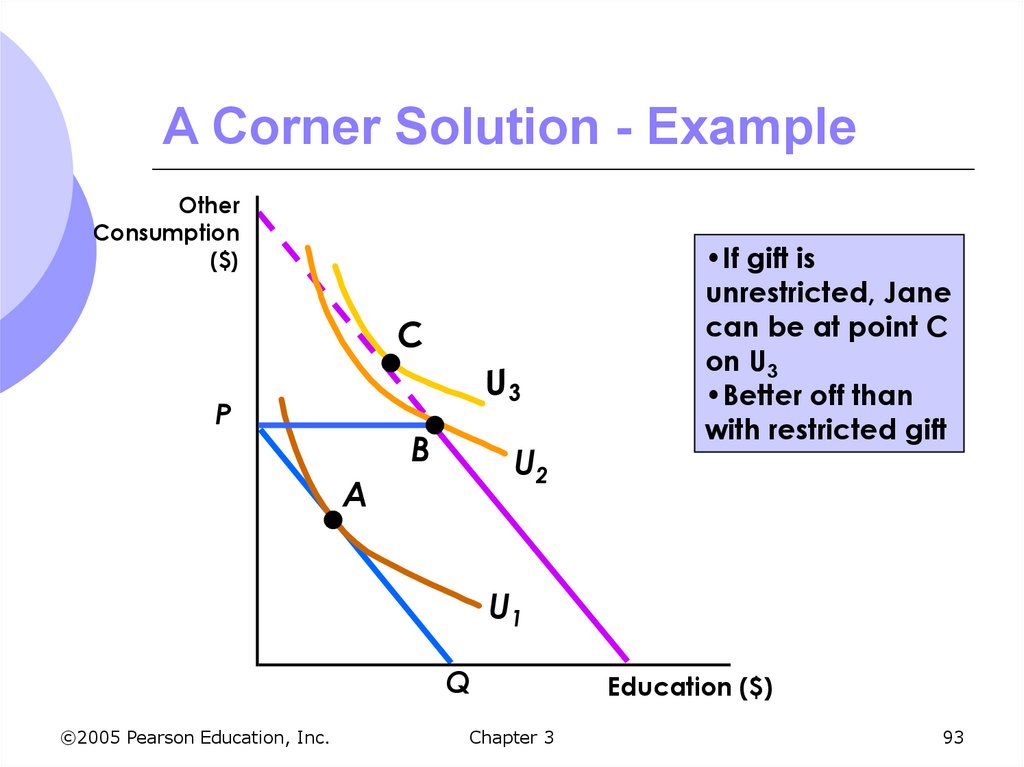

93. A Corner Solution - Example

OtherConsumption

($)

P

B

U2

A

•If gift is

unrestricted, Jane

can be at point C

on U3

•Better off than

with restricted gift

U1

Q

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

Education ($)

93

94. Revealed Preferences

If we know the choices a consumer hasmade, we can determine what their

preferences are if we have information

about a sufficient number of choices that

are made when prices and incomes vary.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

94

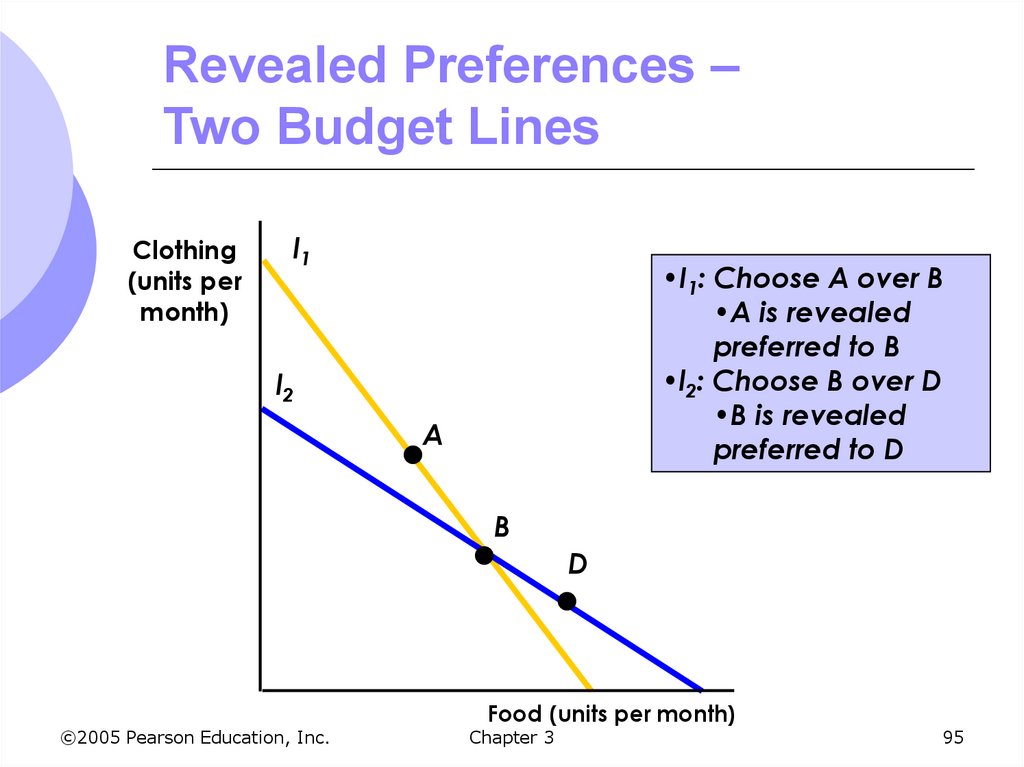

95. Revealed Preferences – Two Budget Lines

Clothing(units per

month)

l1

•I1: Choose A over B

•A is revealed

preferred to B

•l2: Choose B over D

•B is revealed

preferred to D

l2

A

B

D

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Food (units per month)

Chapter 3

95

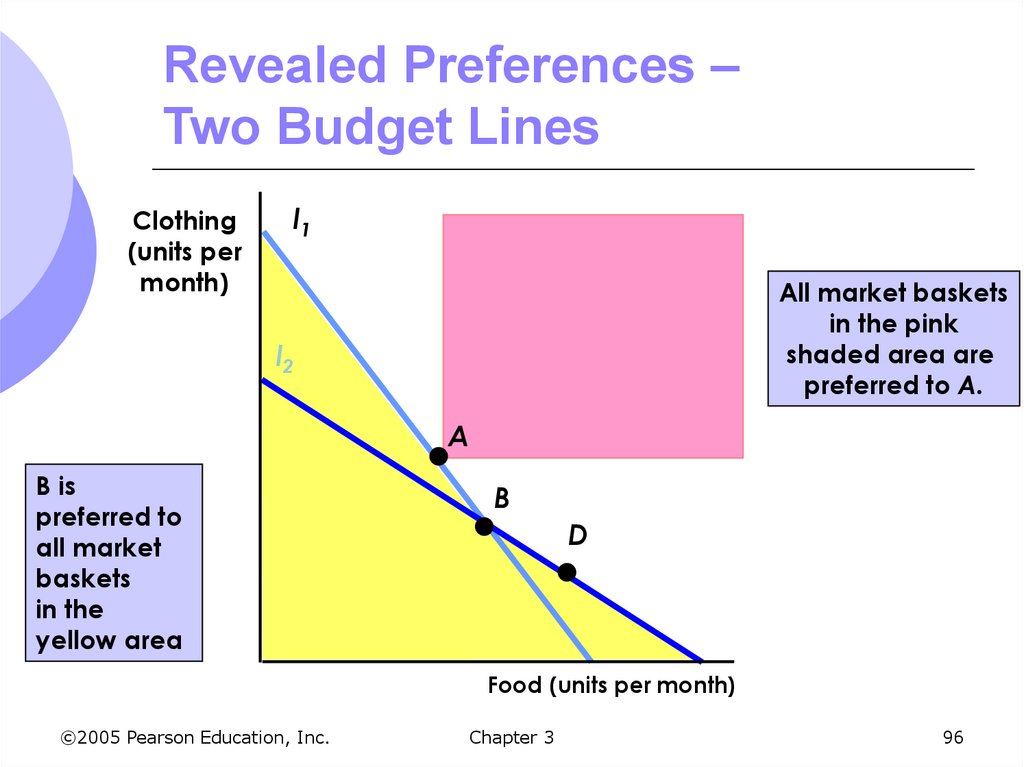

96. Revealed Preferences – Two Budget Lines

Clothing(units per

month)

l1

All market baskets

in the pink

shaded area are

preferred to A.

l2

A

B is

preferred to

all market

baskets

in the

yellow area

B

D

Food (units per month)

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

96

97. Revealed Preference

As you continue to change the budgetline, individuals can tell you which basket

they prefer to others

The more the individual reveals, the more

you can discern about their preferences

Eventually you can map out an

indifference curve

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

97

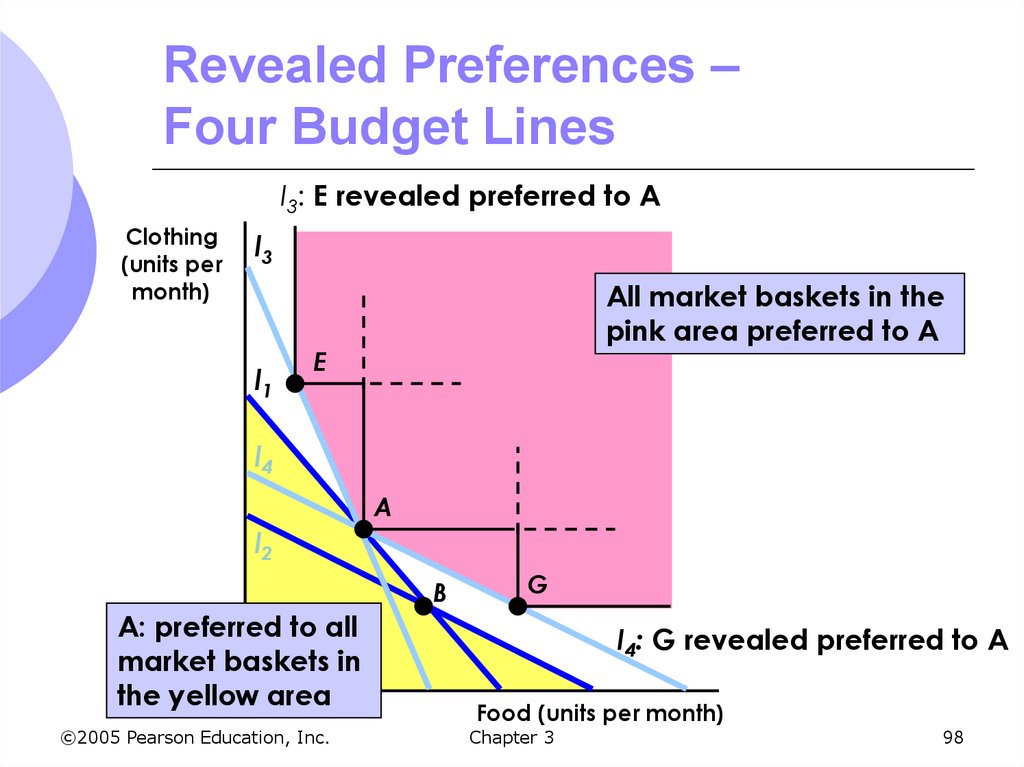

98. Revealed Preferences – Four Budget Lines

I3: E revealed preferred to AClothing

(units per

month)

l3

l1

All market baskets in the

pink area preferred to A

E

l4

A

l2

B

A: preferred to all

market baskets in

the yellow area

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

G

I4: G revealed preferred to A

Food (units per month)

Chapter 3

98

99. Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice

Marginal utility measures the additionalsatisfaction obtained from consuming

one additional unit of a good

How much happier is the individual from

consuming one more unit of food?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

99

100. Marginal Utility - Example

The marginal utility derived fromincreasing from 0 to 1 units of food might

be 9

Increasing from 1 to 2 might be 7

Increasing from 2 to 3 might be 5

Observation: Marginal utility is

diminishing as consumption increases

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

100

101. Marginal Utility

The principle of diminishing marginalutility states that as more of a good is

consumed, the additional utility the

consumer gains will be smaller and

smaller

Note that total utility will continue to

increase since consumer makes choices

that make them happier

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

101

102. Marginal Utility and Indifference Curves

As consumption moves along anindifference curve:

Additional utility derived from an increase in

the consumption one good, food (F), must

balance the loss of utility from the decrease

in the consumption in the other good,

clothing (C)

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

102

103. Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice

Formally:0 MUF( F) MUC( C)

No change in total utility along an indifference curve.

Trade off of one good to the other leaves the consumer

just as well off.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

103

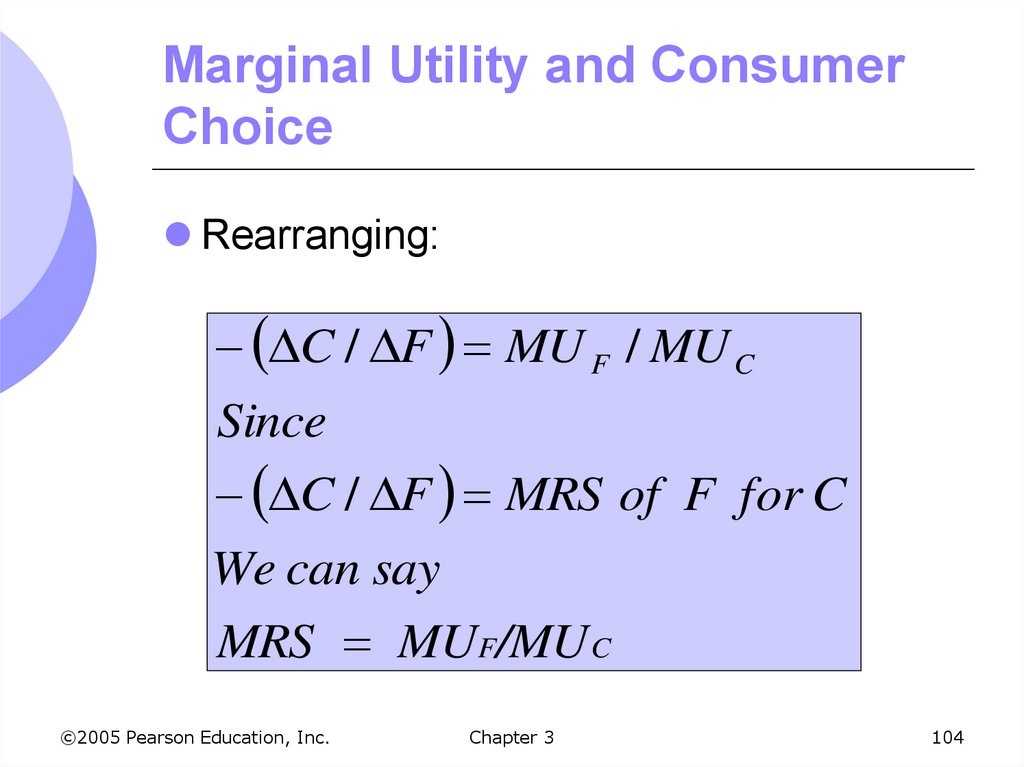

104. Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice

Rearranging:C / F MU F / MU C

Since

C / F MRS of F for C

We can say

MRS MUF/MU C

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

104

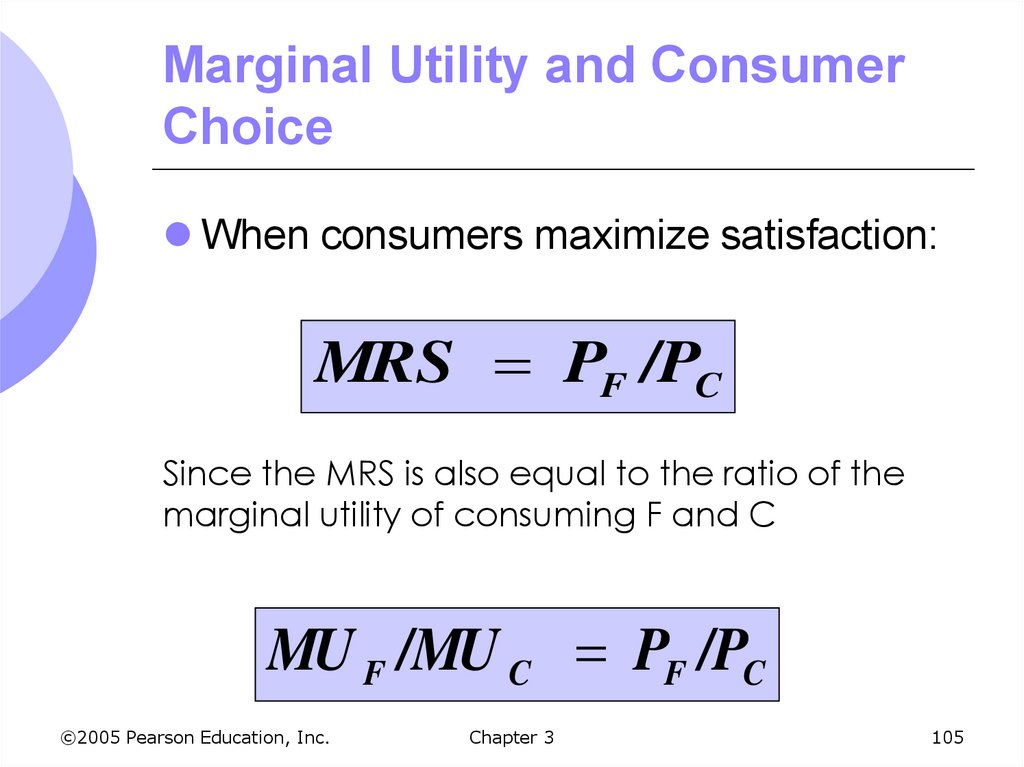

105. Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice

When consumers maximize satisfaction:MRS PF /PC

Since the MRS is also equal to the ratio of the

marginal utility of consuming F and C

MU F /MU C PF /PC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

105

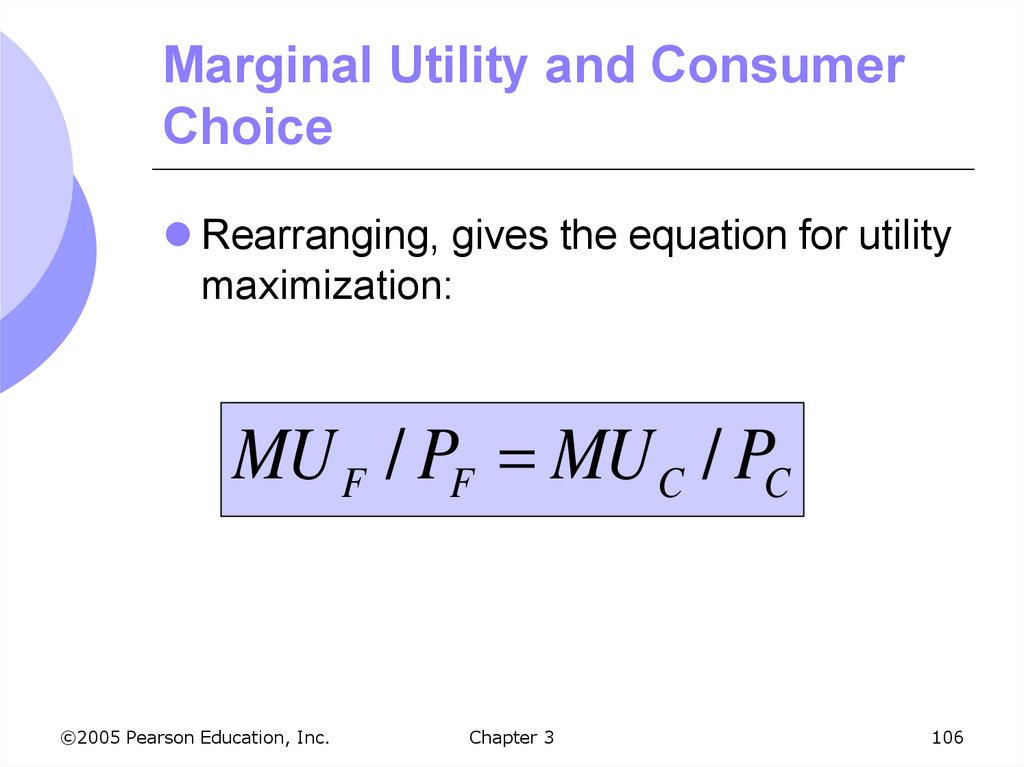

106. Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice

Rearranging, gives the equation for utilitymaximization:

MU F / PF MU C / PC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

106

107. Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice

Total utility is maximized when the budgetis allocated so that the marginal utility per

dollar of expenditure is the same for each

good.

This is referred to as the equal marginal

principle.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

107

108. Cost-of-Living Indexes

Social Security payments are given toqualifying individuals

Each year the benefit increases equal to

the rate of increase of the Consumer

Price Index (CPI)

Ratio of the present cost of typical bundle of

goods/services in comparison to the cost

during a base period

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

108

109. Cost-of-Living Indexes

Does the CPI give a good measure ofinflation and therefore a measure of the

cost of living changes?

Should the CPI be used to measure how

much cost of living has increased,

determining increases in government

payment programs?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

109

110. Cost-of-Living Indexes

The ideal cost of living index representsthe cost of attaining a given level of utility

at current prices relative to the cost of

attaining the same utility at base prices

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

110

111. Cost-of-Living Indexes

To obtain the ideal cost of living indexwould require too much information, such

as consumer preferences as well as

prices and expenditures

Actual price indexes are based on

consumer purchases, not preferences

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

111

112. Cost-of-Living Indexes

Laspeyres price indexAmount of money at current year prices that

an individual requires to purchase a bundle

of goods/services chosen in a base year

divided by the cost of purchasing the same

bundle at base-year prices

Ex: CPI

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

112

113. Cost-of-Living Indexes

The Laspeyres price index assumes thatconsumers do not alter their consumption

patterns as prices change

Tends to overstate the true cost of living

index

Using the CPI to adjust retirement

benefits will tend to overcompensate

most recipients, requiring greater

government expenditure

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

113

114. Cost-of-Living Indexes

Paasche indexFocuses on the cost of buying the current

year’s bundle

Amount of money at current-year prices that

an individual requires to purchase a current

bundle of goods/services divided by the cost

of purchasing the same bundle in a base

year

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

114

115. Cost-of-Living Indexes

Comparison of indexesBoth are fixed weight indexes

Quantities of various goods and services in

each index remain unchanged

Laspeyres index keeps quantities at base

year levels

Paasche index keeps unchanged quantities

at current year levels

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

115

116. Cost-of-Living Indexes

Chain-Weighted IndexesCost-of-living index that accounts for

changes in quantities of goods and services

Introduced to overcome problems that arose

when long-term comparisons were made

using fixed weight price indexes

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 3

116

economics

economics