Similar presentations:

The Cost of Production

1. Chapter 7

The Cost of Production2. Topics to be Discussed

Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?Cost in the Short Run

Cost in the Long Run

Long-Run Versus Short-Run Cost Curves

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

2

3. Topics to be Discussed

Production with Two Outputs:Economies of Scope

Dynamic Changes in Costs:

The Learning Curve

Estimating and Predicting Cost

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

3

4. Introduction

Production technology measures therelationship between input and output

Production technology, together with

prices of factor inputs, determine the

firm’s cost of production

Given the production technology,

managers must choose how to produce

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

4

5. Introduction

The optimal, cost minimizing, level ofinputs can be determined

A firm’s costs depend on the rate of

output and we will show how these costs

are likely to change over time

The characteristics of the firm’s

production technology can affect costs in

the long run and short run

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

5

6. Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?

For a firm to minimize costs, we mustclarify what is meant by costs and how to

measure them

It is clear that if a firm has to rent equipment

or buildings, the rent they pay is a cost

What if a firm owns its own equipment or

building?

How are costs calculated here?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

6

7. Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?

Accountants tend to take a retrospectiveview of firms’ costs, whereas economists

tend to take a forward-looking view

Accounting Cost

Actual expenses plus depreciation charges

for capital equipment

Economic Cost

Cost to a firm of utilizing economic resources

in production, including opportunity cost

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

7

8. Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?

Economic costs distinguish betweencosts the firm can control and those it

cannot

Concept of opportunity cost plays an

important role

Opportunity cost

Cost associated with opportunities that are

foregone when a firm’s resources are not put

to their highest-value use

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

8

9. Opportunity Cost

An ExampleA firm owns its own building and pays no rent

for office space

Does this mean the cost of office space is

zero?

The building could have been rented instead

Foregone rent is the opportunity cost of

using the building for production and should

be included in the economic costs of doing

business

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

9

10. Opportunity Cost

A person starting their own businessmust take into account the opportunity

cost of their time

Could have worked elsewhere making a

competitive salary

Accountants and economists often treat

depreciation differently as well

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

10

11. Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?

Although opportunity costs are hiddenand should be taken into account, sunk

costs should not

Sunk Cost

Expenditure that has been made and cannot

be recovered

Should not influence a firm’s future economic

decisions

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

11

12. Sunk Cost

Firm buys a piece of equipment thatcannot be converted to another use

Expenditure on the equipment is a sunk

cost

Has no alternative use so cost cannot be

recovered – opportunity cost is zero

Decision to buy the equipment might have

been good or bad, but now does not matter

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

12

13. Prospective Sunk Cost

An ExampleFirm is considering moving its headquarters

A firm paid $500,000 for an option to buy a

building

The cost of the building is $5 million for a

total of $5.5 million

The firm finds another building for $5.25

million

Which building should the firm buy?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

13

14. Prospective Sunk Cost

Example (cont.)The first building should be purchased

The $500,000 is a sunk cost and should

not be considered in the decision to buy

What should be considered is

Spending an additional $5,250,000 or

Spending an additional $5,000,000

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

14

15. Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?

Some costs vary with output, whilesome remain the same no matter the

amount of output

Total cost can be divided into:

1. Fixed Cost

Does not vary with the level of output

2. Variable Cost

Cost that varies as output varies

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

15

16. Fixed and Variable Costs

Total output is a function of variableinputs and fixed inputs

Therefore, the total cost of production

equals the fixed cost (the cost of the fixed

inputs) plus the variable cost (the cost of

the variable inputs), or…

TC FC VC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

16

17. Fixed and Variable Costs

Which costs are variable and which arefixed depends on the time horizon

Short time horizon – most costs are fixed

Long time horizon – many costs become

variable

In determining how changes in

production will affect costs, must consider

if fixed or variable costs are affected.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

17

18. Fixed Cost Versus Sunk Cost

Fixed cost and sunk cost are oftenconfused

Fixed Cost

Cost paid by a firm that is in business

regardless of the level of output

Sunk Cost

Cost that has been incurred and cannot be

recovered

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

18

19. Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?

Personal ComputersMost costs are variable

Largest component: labor

Software

Most costs are sunk

Initial cost of developing the software

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

19

20. Marginal and Average Cost

In completing a discussion of costs, mustalso distinguish between

Average Cost

Marginal Cost

After definition of costs is complete, one

can consider the analysis between shortrun and long-run costs

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

20

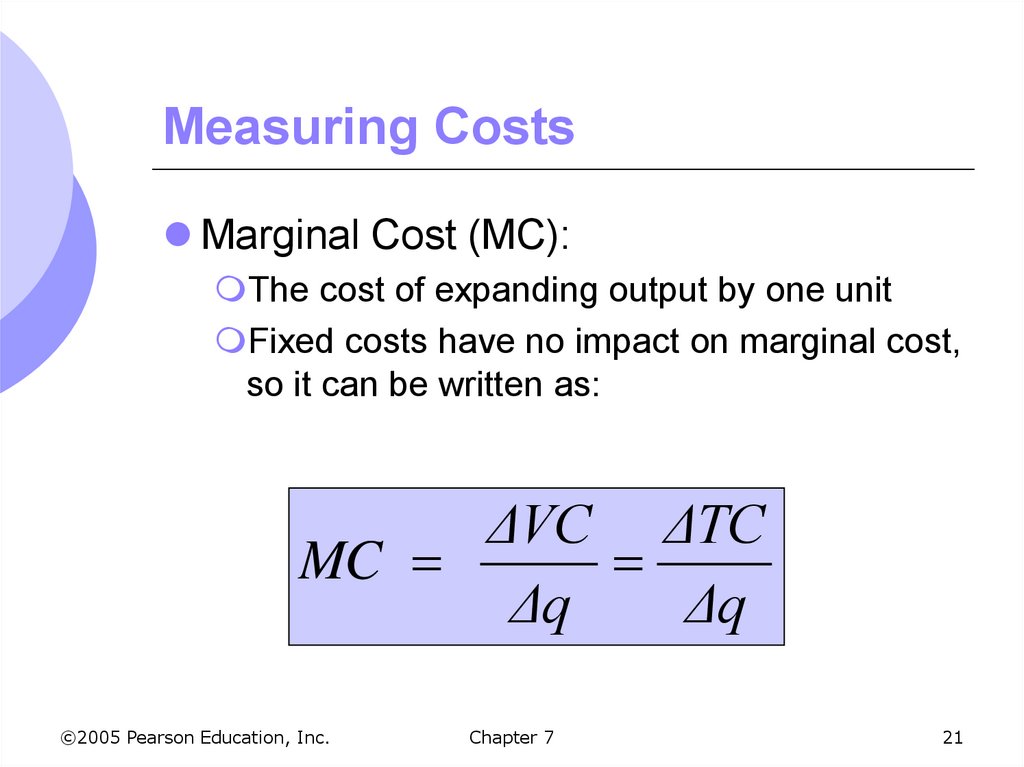

21. Measuring Costs

Marginal Cost (MC):The cost of expanding output by one unit

Fixed costs have no impact on marginal cost,

so it can be written as:

ΔVC ΔTC

MC

Δq

Δq

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

21

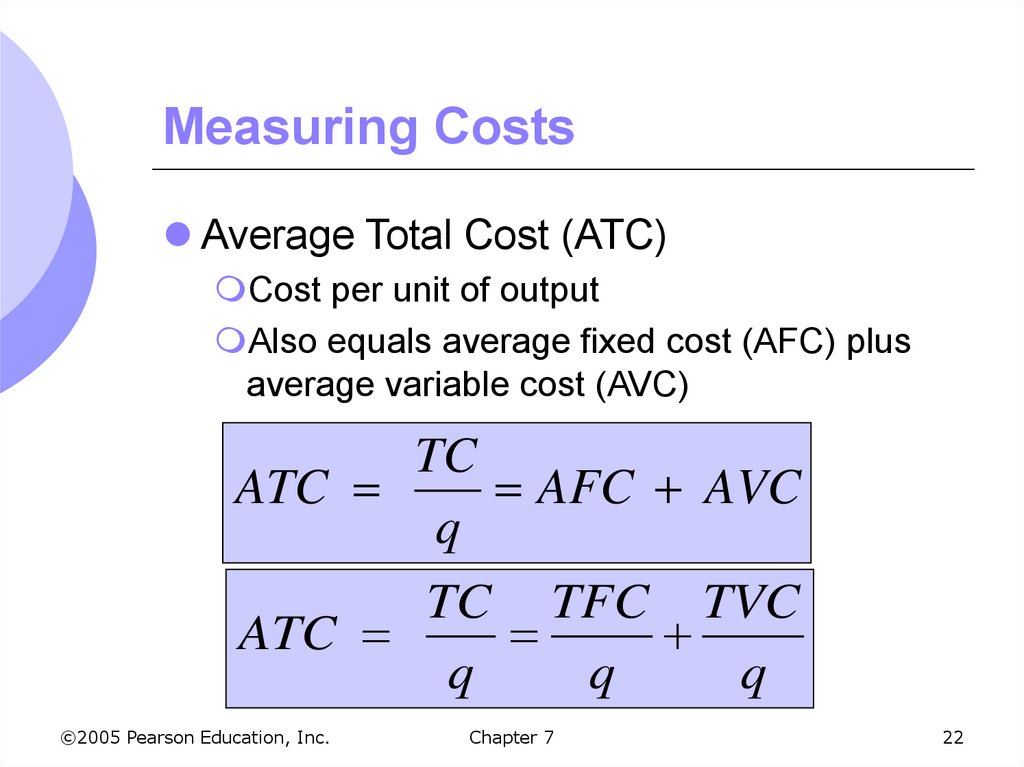

22. Measuring Costs

Average Total Cost (ATC)Cost per unit of output

Also equals average fixed cost (AFC) plus

average variable cost (AVC)

TC

ATC

AFC AVC

q

TC TFC TVC

ATC

q

q

q

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

22

23. Measuring Costs

All the types of costs relevant toproduction have now been discussed

Can now discuss how they differ in the

long and short run

Costs that are fixed in the short run may

not be fixed in the long run

Typically in the long run, most if not all

costs are variable

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

23

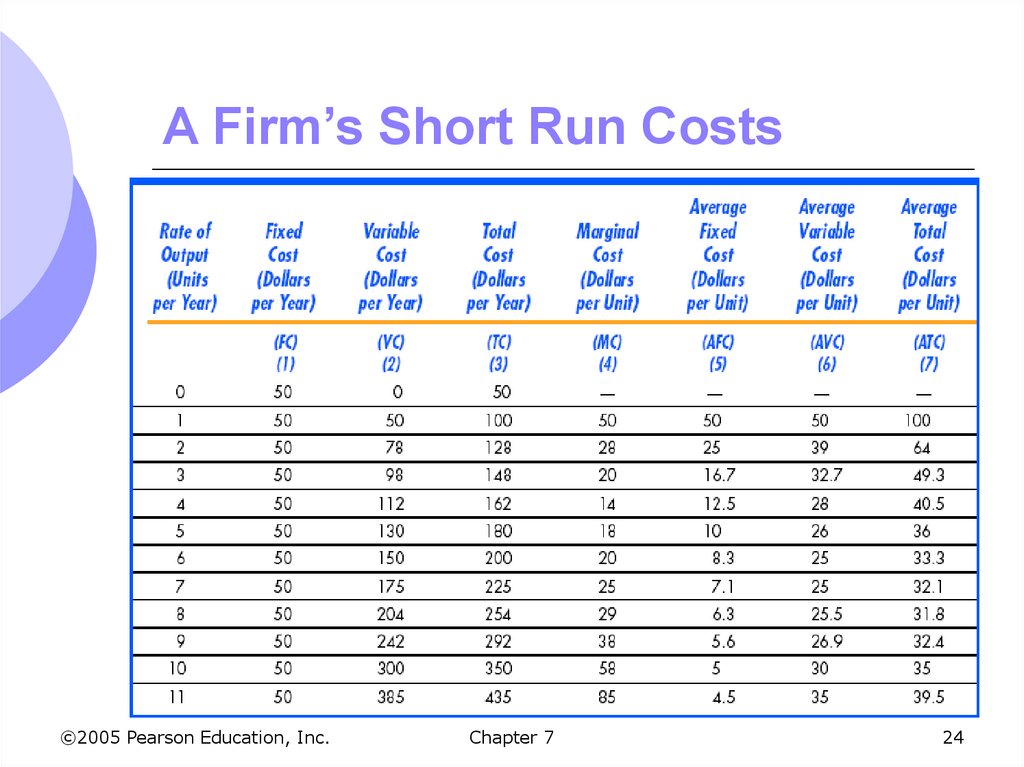

24. A Firm’s Short Run Costs

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.Chapter 7

24

25. Determinants of Short Run Costs

The rate at which these costs increasedepends on the nature of the production

process

The extent to which production involves

diminishing returns to variable factors

Diminishing returns to labor

When marginal product of labor is

decreasing

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

25

26. Determinants of Short Run Costs

If marginal product of labor decreasessignificantly as more labor is hired

Costs of production increase rapidly

Greater and greater expenditures must be

made to produce more output

If marginal product of labor decreases

only slightly as increase labor

Costs will not rise very fast when output is

increased

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

26

27. Determinants of Short Run Costs – An Example

Assume the wage rate (w) is fixedrelative to the number of workers hired

Variable costs is the per unit cost of extra

labor times the amount of extra labor: wL

VC w L

MC

q

q

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

27

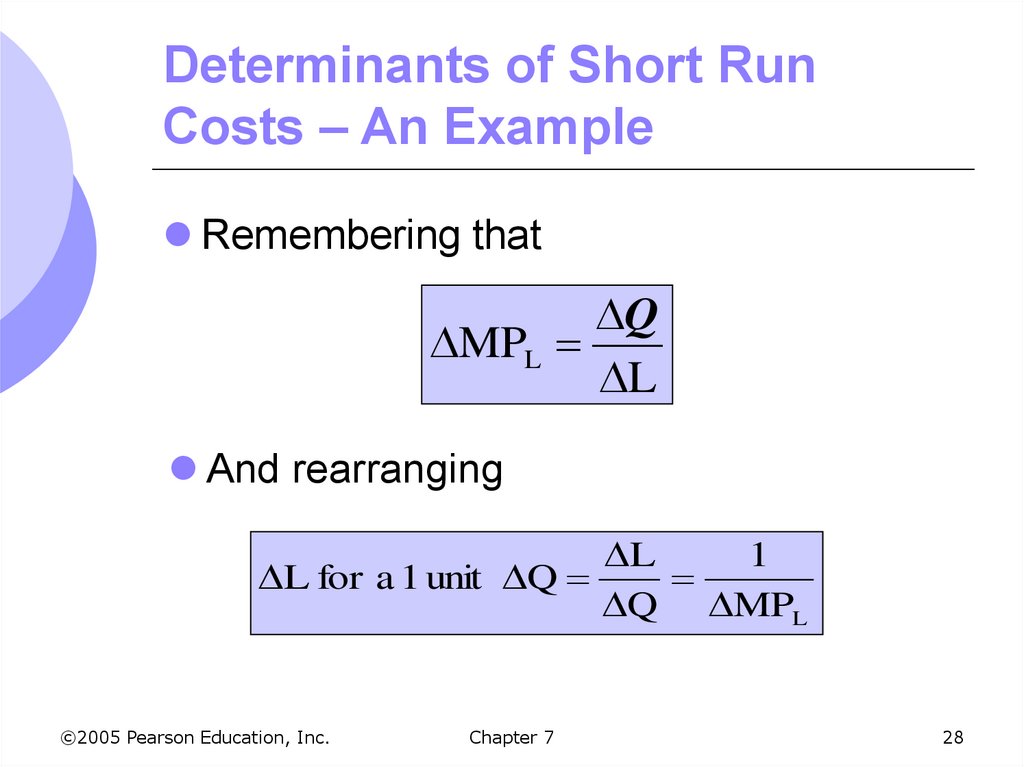

28. Determinants of Short Run Costs – An Example

Remembering thatQ

MPL

L

And rearranging

L

1

L for a 1 unit Q

Q MPL

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

28

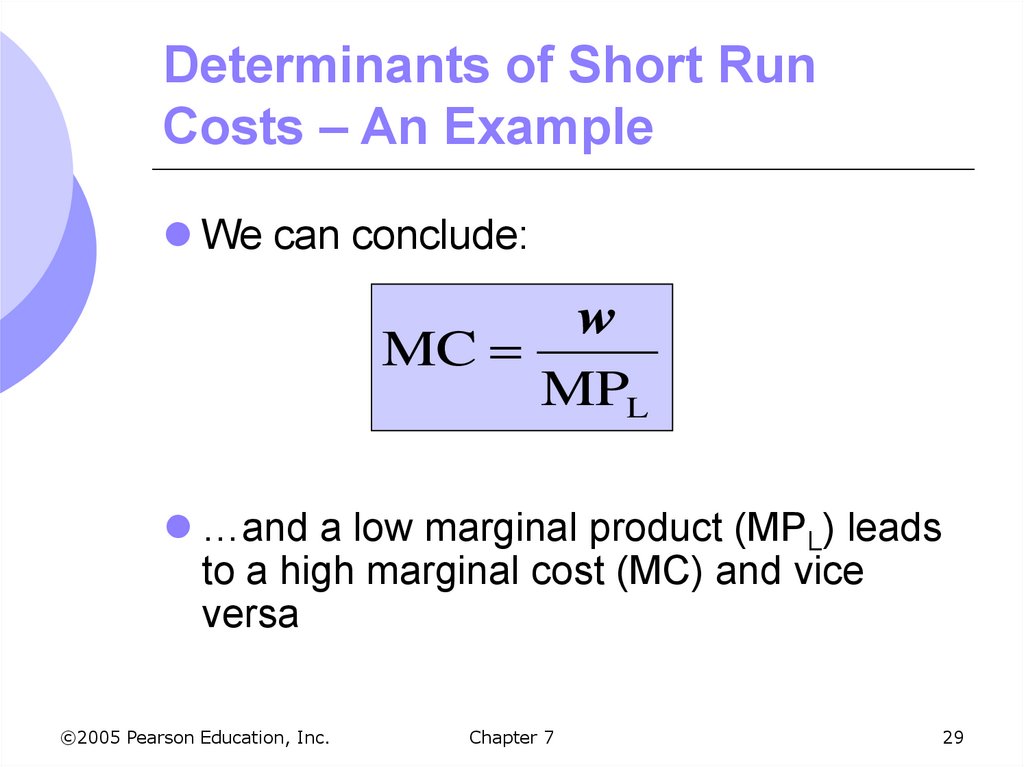

29. Determinants of Short Run Costs – An Example

We can conclude:w

MC

MPL

…and a low marginal product (MPL) leads

to a high marginal cost (MC) and vice

versa

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

29

30. Determinants of Short Run Costs

Consequently (from the table):MC decreases initially with increasing returns

0 through 4 units of output

MC increases with decreasing returns

5 through 11 units of output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

30

31. Cost Curves

The following figures illustrate howvarious cost measures change as

outputs change

Curves based on the information in table

7.1 discussed earlier

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

31

32. Cost Curves for a Firm

TCCost 400

($ per

year)

Total cost

is the vertical

sum of FC

and VC.

300

VC

Variable cost

increases with

production and

the rate varies with

increasing and

decreasing returns.

200

Fixed cost does not

vary with output

100

FC

50

0

1

2

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

3

4

5

6

7

Chapter 7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Output

32

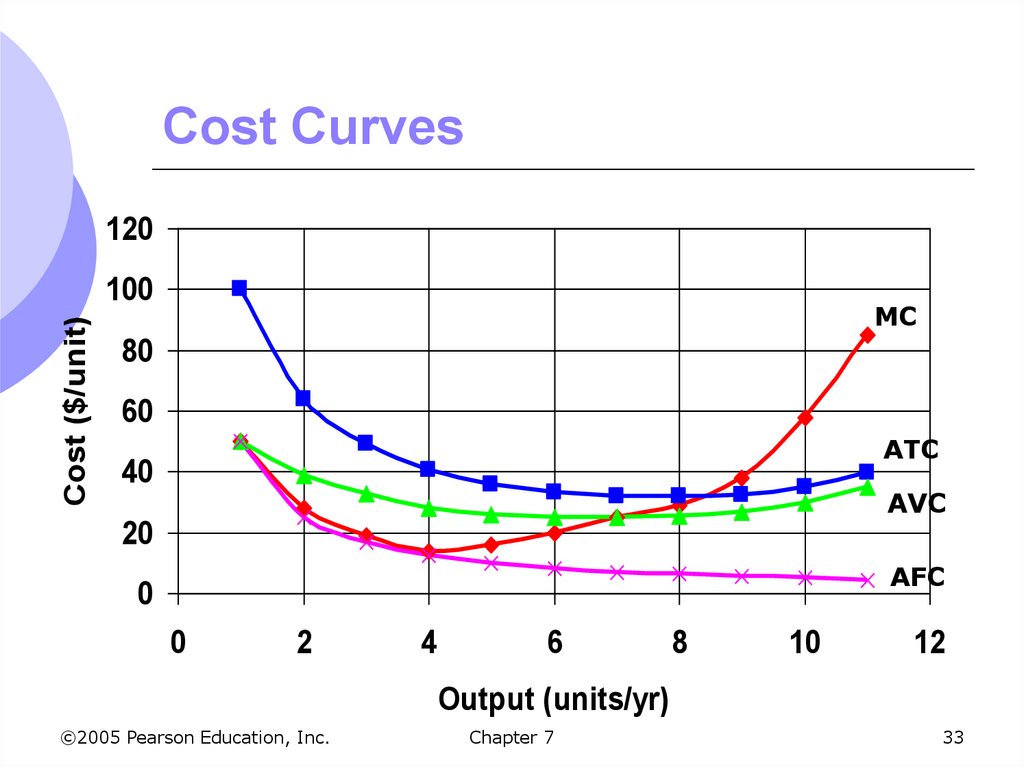

33. Cost Curves

120Cost ($/unit)

100

MC

80

60

ATC

40

AVC

20

AFC

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Output (units/yr)

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

33

34. Cost Curves

When MC is below AVC, AVC is fallingWhen MC is above AVC, AVC is rising

When MC is below ATC, ATC is falling

When MC is above ATC, ATC is rising

Therefore, MC crosses AVC and ATC at

the minimums

The Average – Marginal relationship

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

34

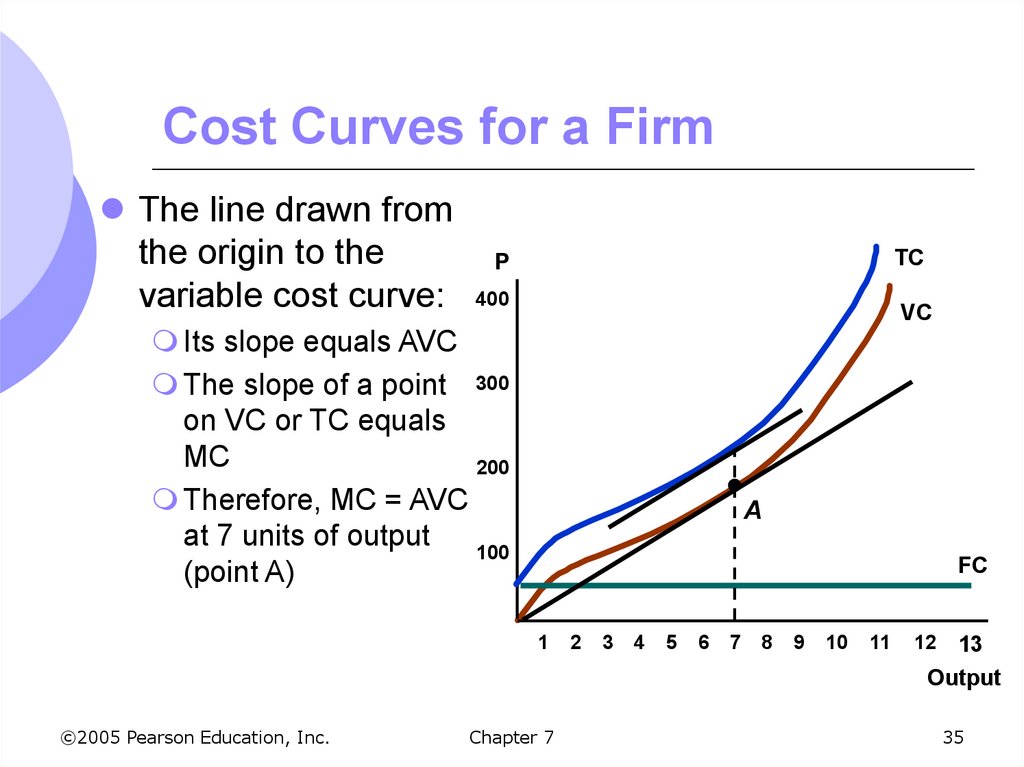

35. Cost Curves for a Firm

The line drawn fromthe origin to the

P

variable cost curve: 400

TC

VC

Its slope equals AVC

The slope of a point 300

on VC or TC equals

MC

200

Therefore, MC = AVC

at 7 units of output

100

(point A)

A

FC

1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Output

35

36. Cost in the Long Run

In the long run a firm can change all of itsinputs

In making cost minimizing choices, must

look at the cost of using capital and labor

in production decisions

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

36

37. Cost in the Long Run

Capital is either rented/leased orpurchased

We will consider capital rented as if it were

purchased

Assume Delta is considering purchasing

an airplane for $150 million

Plane lasts for 30 years

$5 million per year – economic depreciation

for the plane

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

37

38. Cost in the Long Run

Delta needs to compare its revenues andcosts on an annual basis

If the firm had not purchased the plane, it

would have earned interest on the $150

million

Forgone interest is an opportunity cost

that must be considered

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

38

39. User Cost of Capital

The user cost of capital must beconsidered

The annual cost of owning and using the

airplane instead of selling or never buying it

Sum of the economic depreciation and the

interest (the financial return) that could have

been earned had the money been invested

elsewhere

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

39

40. Cost in the Long Run

User Cost of Capital = EconomicDepreciation + (Interest Rate)*(Value of

Capital)

= $5 mil + (.10)($150 mil – depreciation)

Year 1 = $5 million + (.10)($150 million) =

$20 million

Year 10 = $5 million +(.10)($100 million) =

$15 million

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

40

41. Cost in the Long Run

User cost can also be described as:Rate per dollar of capital, r

r = Depreciation Rate + Interest Rate

In our example, depreciation rate was

3.33% and interest was 10%, so

r = 3.33% + 10% = 13.33%

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

41

42. Cost Minimizing Input Choice

How do we put all this together to select inputsto produce a given output at minimum cost?

Assumptions

Two Inputs: Labor (L) and capital (K)

Price of labor: wage rate (w)

The price of capital

r = depreciation rate + interest rate

Or rental rate if not purchasing

These are equal in a competitive

capital market

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

42

43. Cost in the Long Run

The Isocost LineA line showing all combinations of L & K that

can be purchased for the same cost

Total cost of production is sum of firm’s labor

cost, wL, and its capital cost, rK:

C = wL + rK

For each different level of cost, the equation

shows another isocost line

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

43

44. Cost in the Long Run

Rewriting C as an equation for a straightline:

K = C/r - (w/r)L

Slope of the isocost: K L w r

-(w/r) is the ratio of the wage rate to rental cost

of capital.

This shows the rate at which capital can be

substituted for labor with no change in cost

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

44

45. Choosing Inputs

We will address how to minimize cost fora given level of output by combining

isocosts with isoquants

We choose the output we wish to

produce and then determine how to do

that at minimum cost

Isoquant is the quantity we wish to produce

Isocost is the combination of K and L that

gives a set cost

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

45

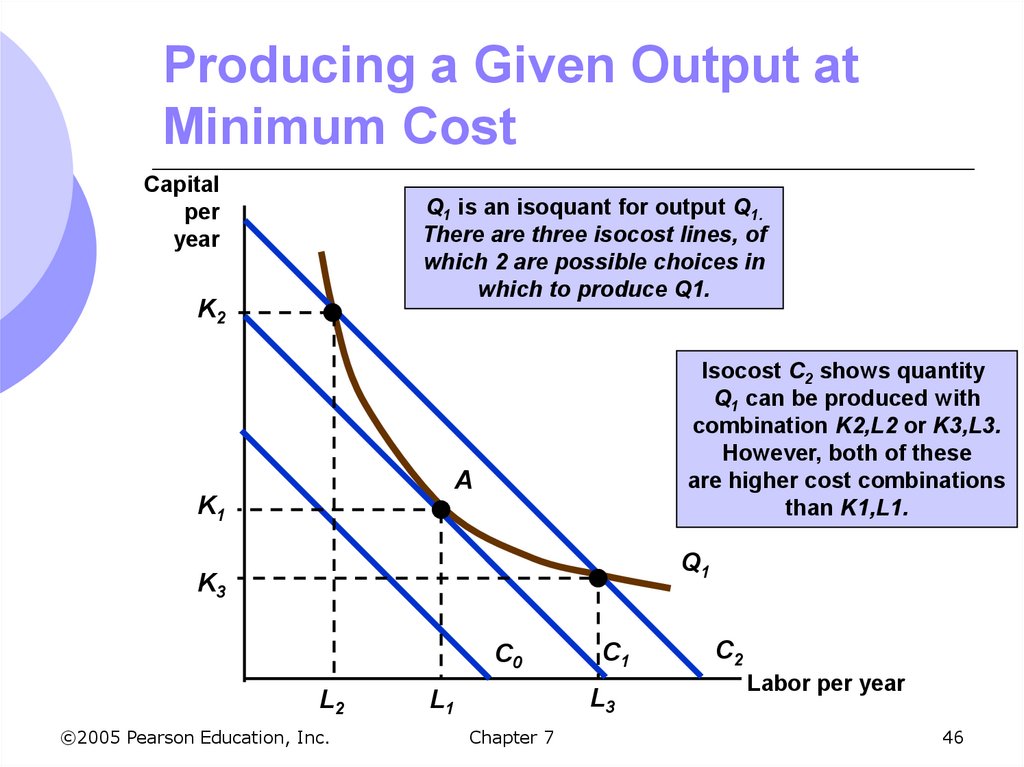

46. Producing a Given Output at Minimum Cost

Capitalper

year

Q1 is an isoquant for output Q1.

There are three isocost lines, of

which 2 are possible choices in

which to produce Q1.

K2

Isocost C2 shows quantity

Q1 can be produced with

combination K2,L2 or K3,L3.

However, both of these

are higher cost combinations

than K1,L1.

A

K1

Q1

K3

C0

L2

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

C1

L3

L1

Chapter 7

C2

Labor per year

46

47. Input Substitution When an Input Price Change

If the price of labor changes, then theslope of the isocost line changes, -(w/r)

It now takes a new quantity of labor and

capital to produce the output

If price of labor increases relative to price

of capital, and capital is substituted for

labor

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

47

48. Input Substitution When an Input Price Change

Capitalper

year

If the price of labor

rises, the isocost curve

becomes steeper due to

the change in the slope -(w/L).

The new combination of K

and L is used to produce Q1.

Combination B is used in

place of combination A.

B

K2

A

K1

Q1

C2

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

L2

L1

Chapter 7

C1

Labor per year

48

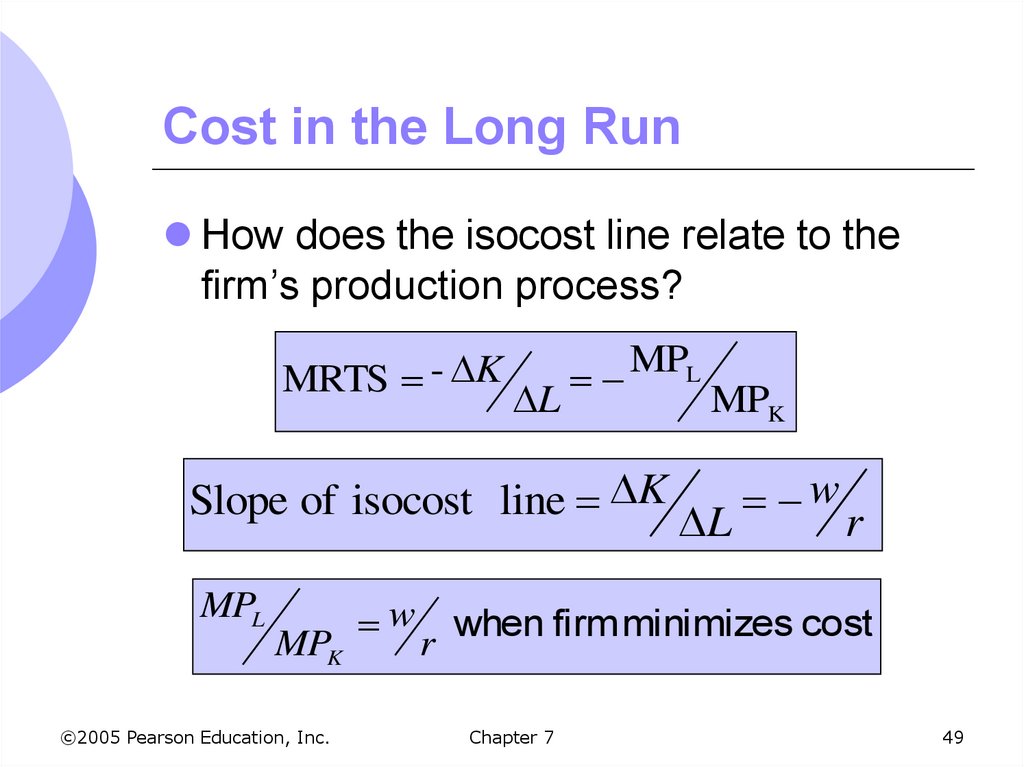

49. Cost in the Long Run

How does the isocost line relate to thefirm’s production process?

MRTS - K

L

MPL

Slope of isocost line K

MPL

MPK

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

w

r

MPK

L

w

r

when firm minimizes cost

Chapter 7

49

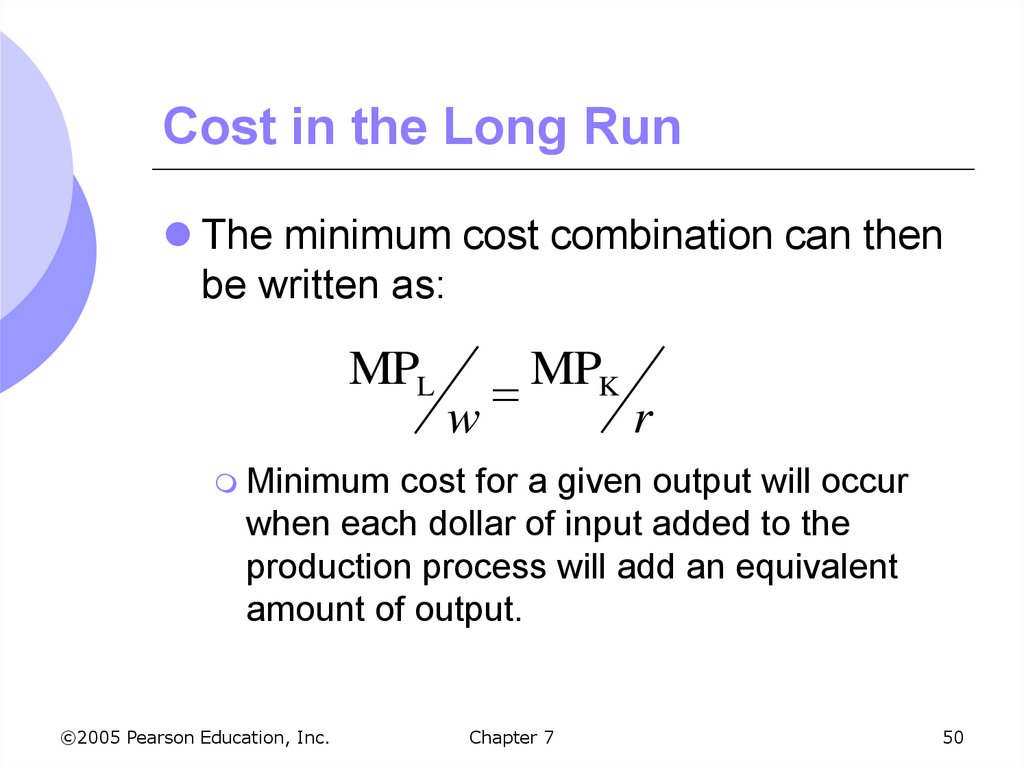

50. Cost in the Long Run

The minimum cost combination can thenbe written as:

MPL

w

MP

K

r

Minimum cost for a given output will occur

when each dollar of input added to the

production process will add an equivalent

amount of output.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

50

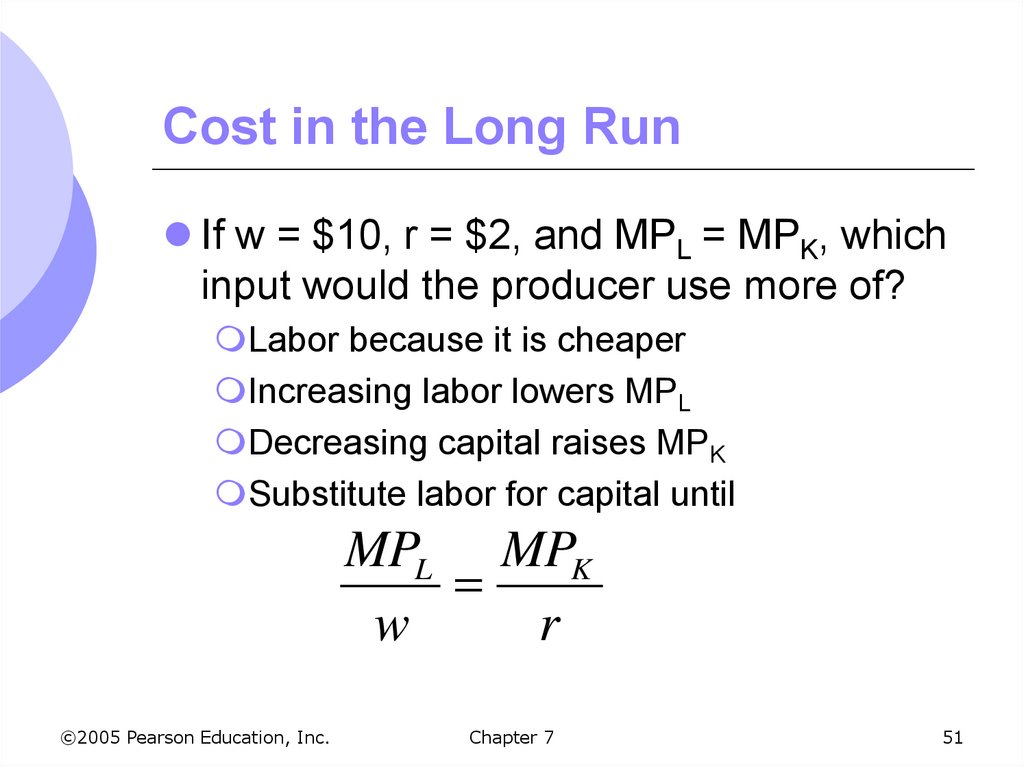

51. Cost in the Long Run

If w = $10, r = $2, and MPL = MPK, whichinput would the producer use more of?

Labor because it is cheaper

Increasing labor lowers MPL

Decreasing capital raises MPK

Substitute labor for capital until

MPL MPK

w

r

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

51

52. Cost in the Long Run

Cost minimization with Varying OutputLevels

For each level of output, there is an isocost

curve showing minimum cost for that output

level

A firm’s expansion path shows the minimum

cost combinations of labor and capital at

each level of output

Slope equals K/ L

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

52

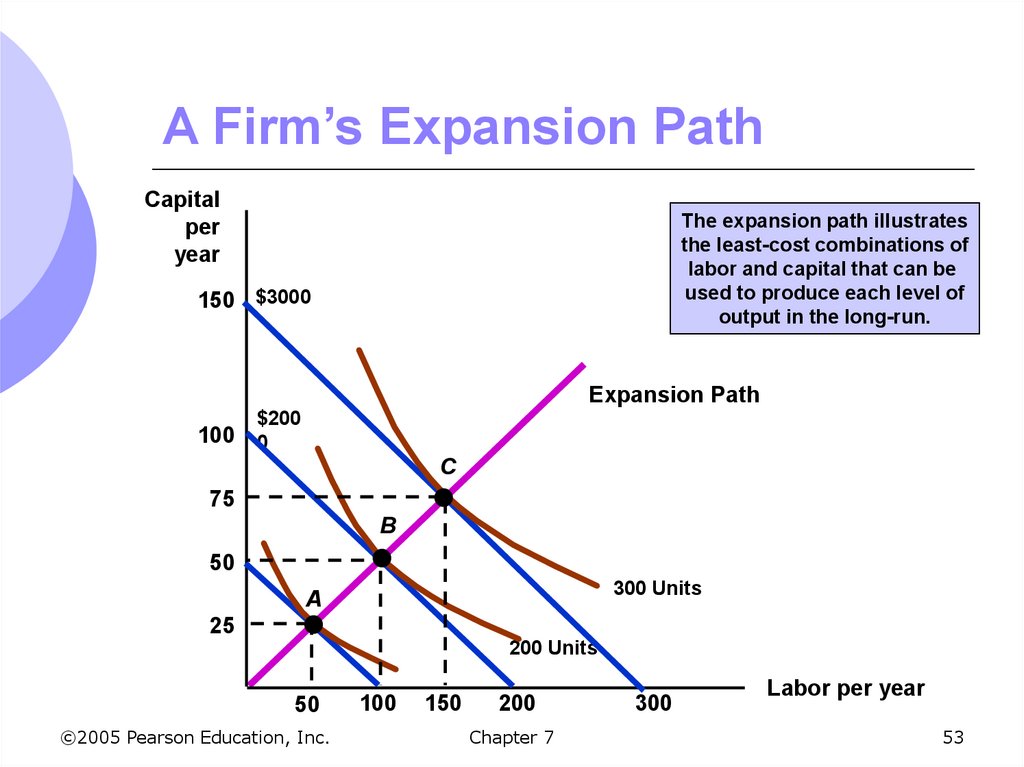

53. A Firm’s Expansion Path

Capitalper

year

The expansion path illustrates

the least-cost combinations of

labor and capital that can be

used to produce each level of

output in the long-run.

150 $3000

Expansion Path

$200

100 0

C

75

B

50

300 Units

A

25

200 Units

50

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

100

150

200

Chapter 7

300

Labor per year

53

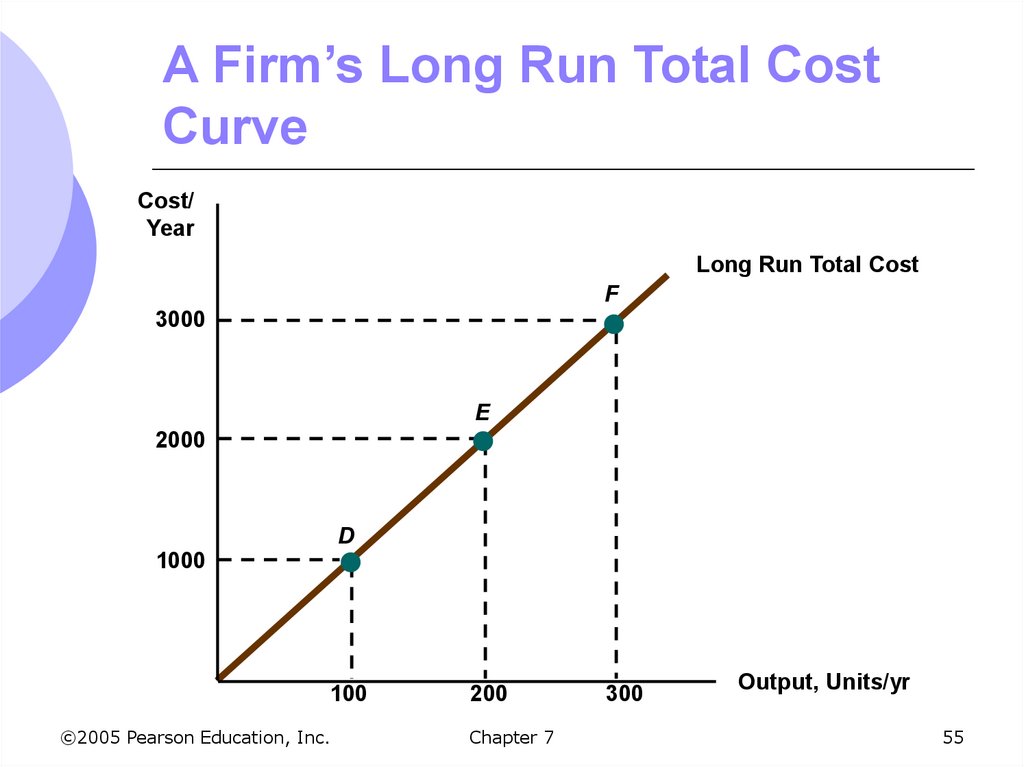

54. Expansion Path and Long Run Costs

Firm’s expansion path has sameinformation as long-run total cost curve

To move from expansion path to LR cost

curve

Find tangency with isoquant and isocost

Determine min cost of producing the output

level selected

Graph output-cost combination

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

54

55. A Firm’s Long Run Total Cost Curve

Cost/Year

Long Run Total Cost

F

3000

E

2000

D

1000

100

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

200

Chapter 7

300

Output, Units/yr

55

56. Long Run Versus Short Run Cost Curves

In the short run, some costs are fixedIn the long run, firm can change anything

including plant size

Can produce at a lower average cost in long

run than in short run

Capital and labor are both flexible

We can show this by holding capital fixed

in the short run and flexible in long run

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

56

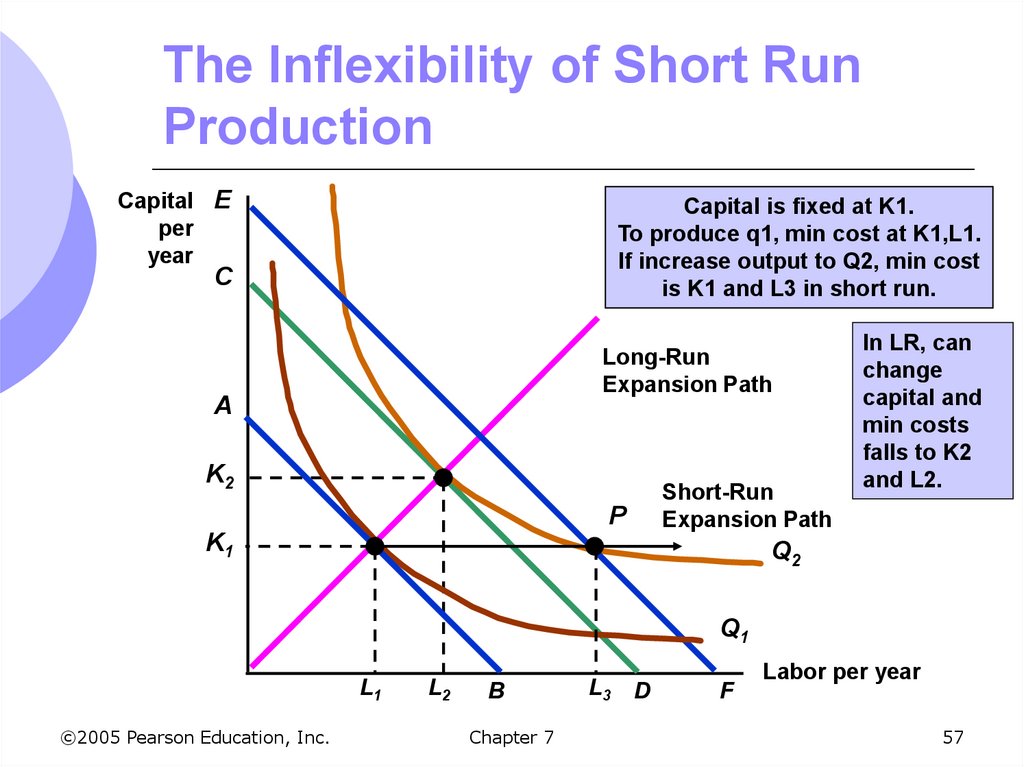

57. The Inflexibility of Short Run Production

Capital Eper

year

Capital is fixed at K1.

To produce q1, min cost at K1,L1.

If increase output to Q2, min cost

is K1 and L3 in short run.

C

Long-Run

Expansion Path

A

K2

Short-Run

Expansion Path

P

K1

In LR, can

change

capital and

min costs

falls to K2

and L2.

Q2

Q1

L1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

L2

B

Chapter 7

L3

D

F

Labor per year

57

58. Long Run Versus Short Run Cost Curves

Long-Run Average Cost (LAC)Most important determinant of the shape of

the LR AC and MC curves is relationship

between scale of the firm’s operation and

inputs required to minimize cost

1. Constant Returns to Scale

If input is doubled, output will double

AC cost is constant at all levels of output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

58

59. Long Run Versus Short Run Cost Curves

2. Increasing Returns to ScaleIf input is doubled, output will more than

double

AC decreases at all levels of output

3. Decreasing Returns to Scale

If input is doubled, output will less than

double

AC increases at all levels of output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

59

60. Long Run Versus Short Run Cost Curves

In the long run:Firms experience increasing and decreasing

returns to scale and therefore long-run

average cost is “U” shaped.

Source of U-shape is due to returns to scale

instead of decreasing returns to scale like the

short-run curve

Long-run marginal cost curve measures the

change in long-run total costs as output is

increased by 1 unit

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

60

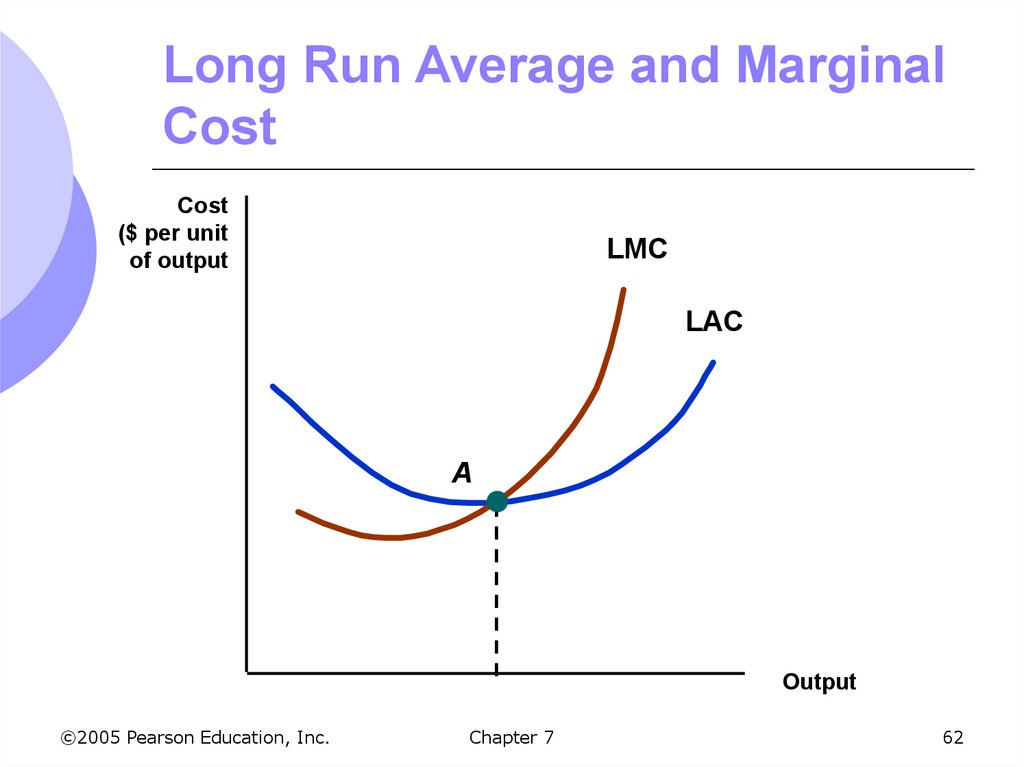

61. Long Run Versus Short Run Cost Curves

Long-run marginal cost leads long-runaverage cost:

If LMC < LAC, LAC will fall

If LMC > LAC, LAC will rise

Therefore, LMC = LAC at the minimum of

LAC

In special case where LAC is constant,

LAC and LMC are equal

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

61

62. Long Run Average and Marginal Cost

Cost($ per unit

of output

LMC

LAC

A

Output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

62

63. Long Run Costs

As output increases, firm’s AC ofproducing is likely to decline to a point

1. On a larger scale, workers can better

specialize

2. Scale can provide flexibility – managers can

organize production more effectively

3. Firm may be able to get inputs at lower cost

if can get quantity discounts. Lower prices

might lead to different input mix.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

63

64. Long Run Costs

At some point, AC will begin to increase1. Factory space and machinery may make it

more difficult for workers to do their jobs

efficiently

2. Managing a larger firm may become more

complex and inefficient as the number of

tasks increase

3. Bulk discounts can no longer be utilized.

Limited availability of inputs may cause

price to rise.

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

64

65. Long Run Costs

When input proportions change, thefirm’s expansion path is no longer a

straight line

Concept of return to scale no longer applies

Economies of scale reflects input

proportions that change as the firm

changes its level of production

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

65

66. Economies and Diseconomies of Scale

Economies of ScaleIncrease in output is greater than the

increase in inputs

Diseconomies of Scale

Increase in output is less than the increase in

inputs

U-shaped LAC shows economies of

scale for relatively low output levels and

diseconomies of scale for higher levels

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

66

67. Long Run Costs

Increasing Returns to ScaleOutput more than doubles when the

quantities of all inputs are doubled

Economies of Scale

Doubling of output requires less than a

doubling of cost

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

67

68. Long Run Costs

Economies of scale are measured interms of cost-output elasticity, EC

EC is the percentage change in the cost

of production resulting from a 1-percent

increase in output

C

C

EC

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Q Q

Chapter 7

MC

AC

68

69. Long Run Costs

EC is equal to 1, MC = ACCosts increase proportionately with output

Neither economies nor diseconomies of scale

EC < 1 when MC < AC

Economies of scale

Both MC and AC are declining

EC > 1 when MC > AC

Diseconomies of scale

Both MC and AC are rising

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

69

70. Long Run Versus Short Run Cost Curves

We will use short and long run costs todetermine the optimal plant size

We can show the short run average costs

for 3 different plant sizes

This decision is important because once

built, the firm may not be able to change

plant size for a while

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

70

71. Long Run Cost with Constant Returns to Scale

The optimal plant size will depend on theanticipated output

If expect to produce q0, then should build

smallest plant: AC = $8

If produce more, like q1, AC rises

If expect to produce q2, middle plant is least

cost

If expect to produce q3, largest plant is best

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

71

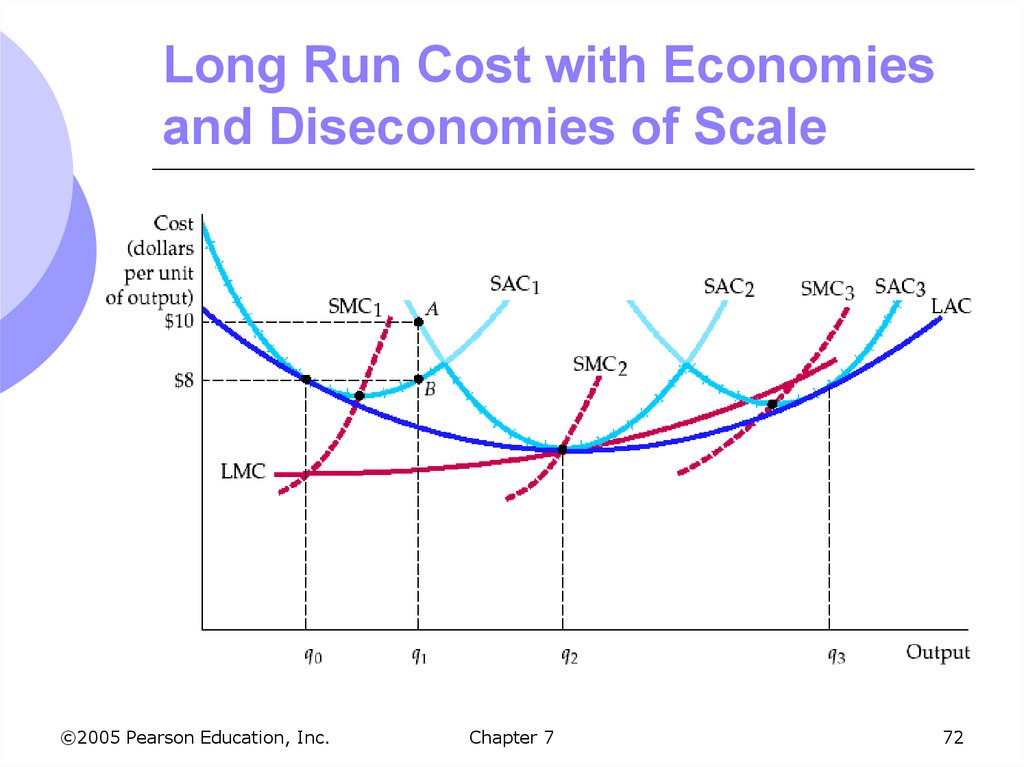

72. Long Run Cost with Economies and Diseconomies of Scale

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.Chapter 7

72

73. Long Run Cost with Constant Returns to Scale

What is the firm’s long run cost curve?Firms can change scale to change output in

the long run

The long run cost curve is the dark blue

portion of the SAC curve which represents

the minimum cost for any level of output

Firm will always choose plant that minimizes

the average cost of production

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

73

74. Long Run Cost with Constant Returns to Scale

The long-run average cost curveenvelops the short-run average cost

curves

The LAC curve exhibits economies of

scale initially but exhibits diseconomies

at higher output levels

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

74

75. Production with Two Outputs – Economies of Scope

Many firms produce more than oneproduct and those products are closely

linked

Examples:

Chicken farm--poultry and eggs

Automobile company--cars and trucks

University--teaching and research

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

75

76. Production with Two Outputs – Economies of Scope

Advantages1. Both use capital and labor

2. The firms share management resources

3. Both use the same labor skills and

types of machinery

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

76

77. Production with Two Outputs – Economies of Scope

Firms must choose how much of each toproduce

The alternative quantities can be

illustrated using product transformation

curves

Curves showing the various combinations of

two different outputs (products) that can be

produced with a given set of inputs

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

77

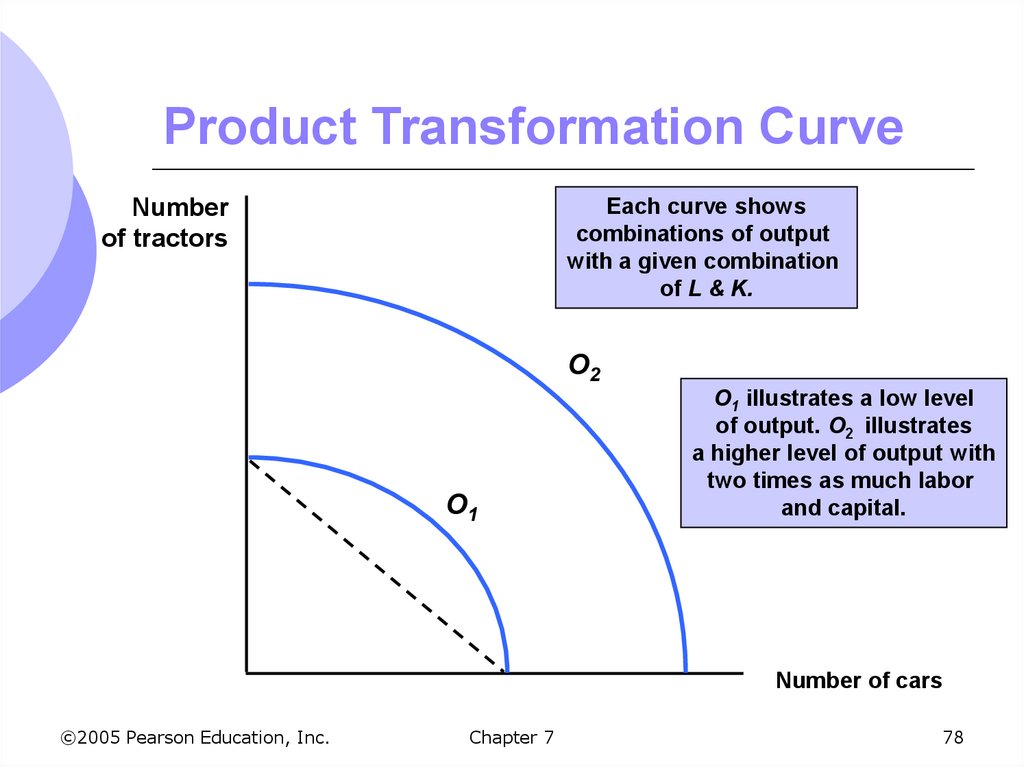

78. Product Transformation Curve

Numberof tractors

Each curve shows

combinations of output

with a given combination

of L & K.

O2

O1

O1 illustrates a low level

of output. O2 illustrates

a higher level of output with

two times as much labor

and capital.

Number of cars

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

78

79. Product Transformation Curve

Product transformation curves arenegatively sloped

To get more of one output, must give up

some of the other output

Constant returns exist in this example

Second curve lies twice as far from origin as

the first curve

Curve is concave

Joint production has its advantages

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

79

80. Production with Two Outputs – Economies of Scope

There is no direct relationship betweeneconomies of scope and economies of

scale

May experience economies of scope and

diseconomies of scale

May have economies of scale and not have

economies of scope

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

80

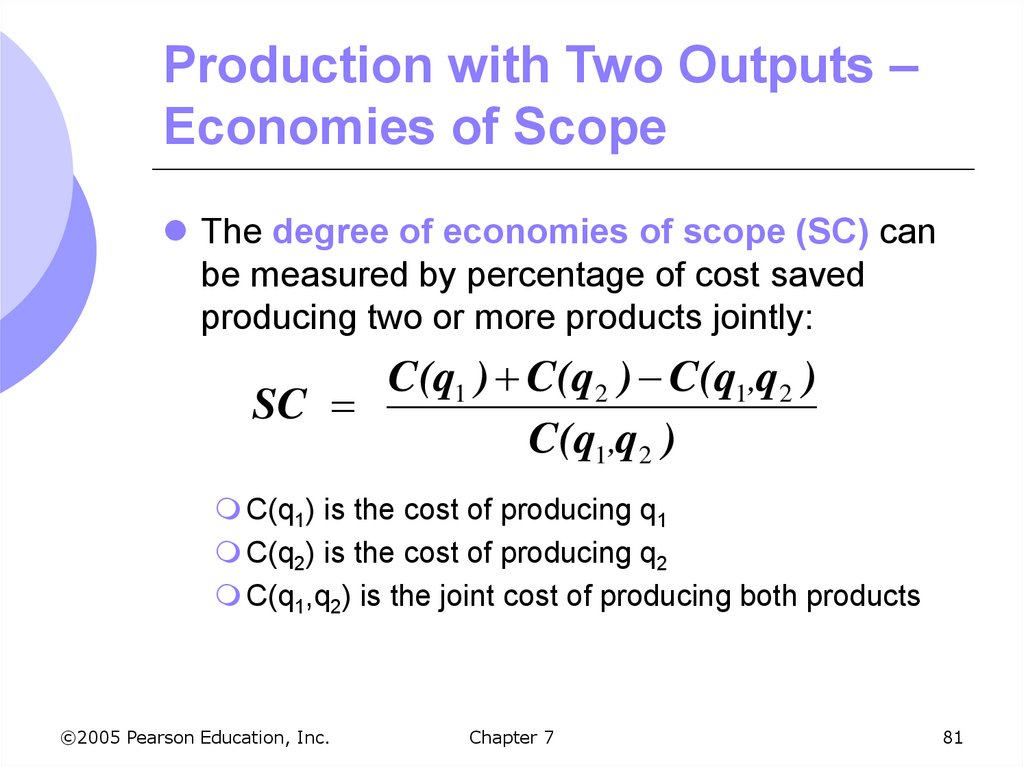

81. Production with Two Outputs – Economies of Scope

The degree of economies of scope (SC) canbe measured by percentage of cost saved

producing two or more products jointly:

C(q1 ) C(q2 ) C(q1 ,q2 )

SC

C(q1 ,q2 )

C(q1) is the cost of producing q1

C(q2) is the cost of producing q2

C(q1,q2) is the joint cost of producing both products

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

81

82. Production with Two Outputs – Economies of Scope

With economies of scope, the joint cost isless than the sum of the individual costs

Interpretation:

If SC > 0 Economies of scope

If SC < 0 Diseconomies of scope

The greater the value of SC, the greater the

economies of scope

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

82

83. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

Firms may lower their costs not only dueto economies of scope, but also due to

managers and workers becoming more

experienced at their jobs

As management and labor gain

experience with production, the firm’s

marginal and average costs may fall

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

83

84. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

Reasons1. Speed of work increases with experience

2. Managers learn to schedule production

processes more efficiently

3. More flexibility is allowed with experience;

may include more specialized tools and

plant organization

4. Suppliers become more efficient, passing

savings to company

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

84

85. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

The learning curve measures the impactof workers’ experience on the costs of

production

It describes the relationship between a

firm’s cumulative output and the amount

of inputs needed to produce a unit of

output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

85

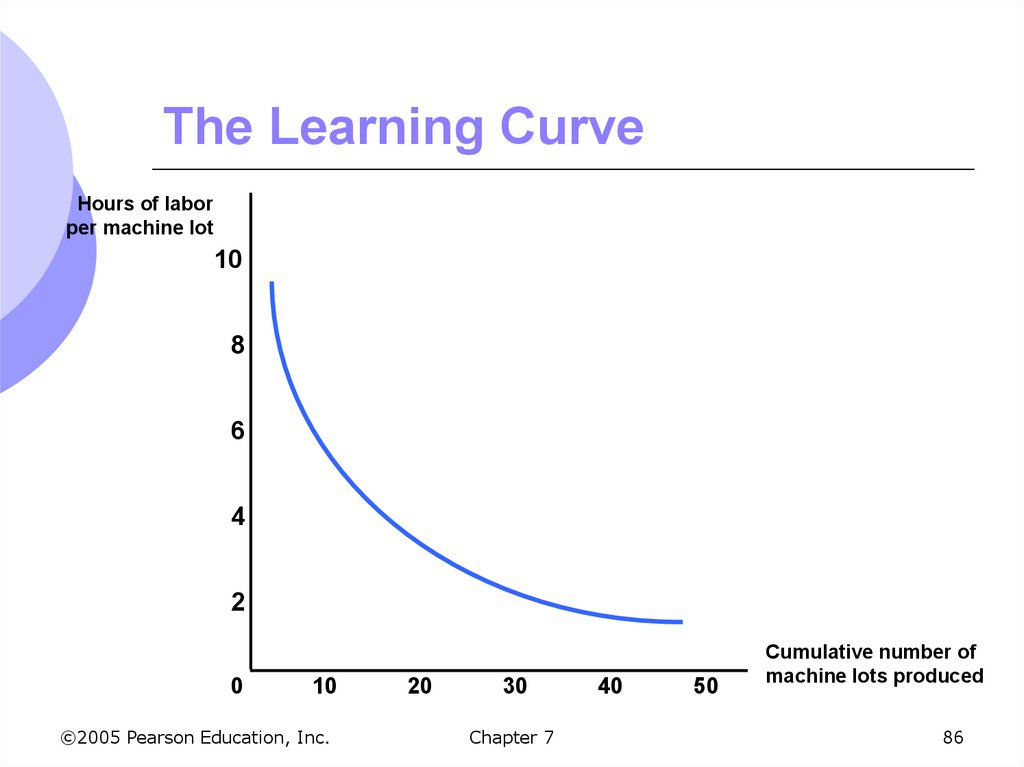

86. The Learning Curve

Hours of laborper machine lot

10

8

6

4

2

0

10

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

20

30

Chapter 7

40

50

Cumulative number of

machine lots produced

86

87. The Learning Curve

The horizontal axis measures thecumulative number of hours of machine

tools the firm has produced

The vertical axis measures the number of

hours of labor needed to produce each

lot

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

87

88. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

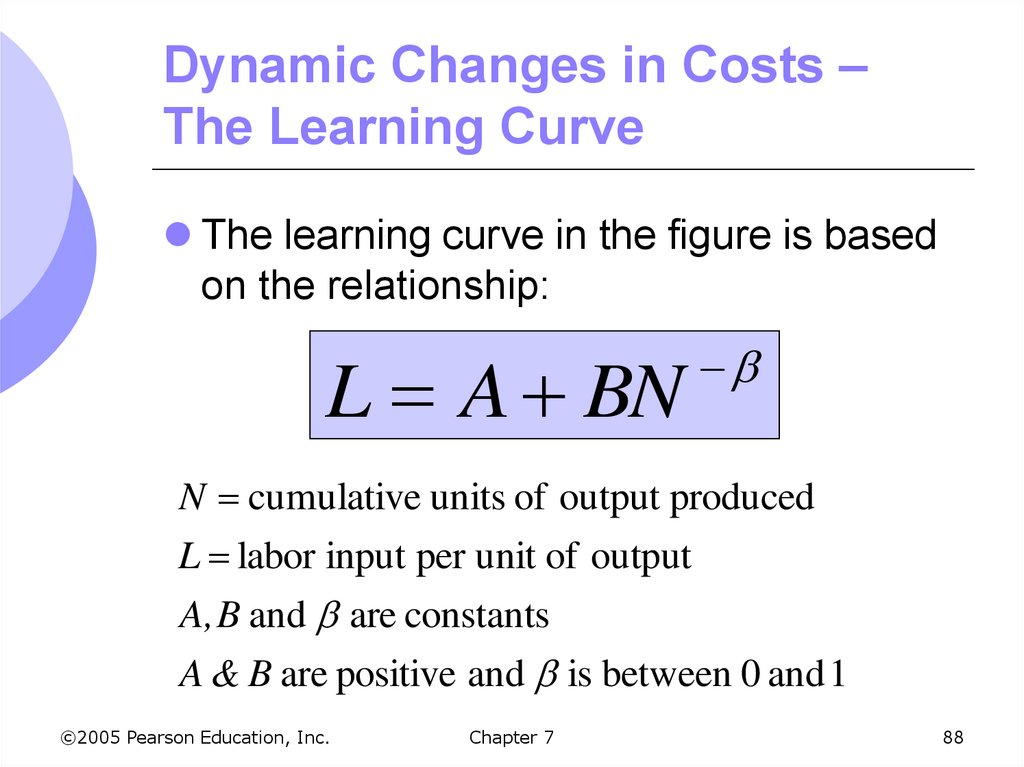

The learning curve in the figure is basedon the relationship:

L A BN

N cumulative units of output produced

L labor input per unit of output

A, B and are constants

A & B are positive and is between 0 and 1

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

88

89. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

If N = 1L equals A + B and this measures labor input

to produce the first unit of output

If = 0

Labor input per unit of output remains

constant as the cumulative level of output

increases, so there is no learning

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

89

90. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

If > 0 and N increases,L approaches A, and A represents minimum

labor input/unit of output after all learning has

taken place

The larger ,

The more important the learning effect

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

90

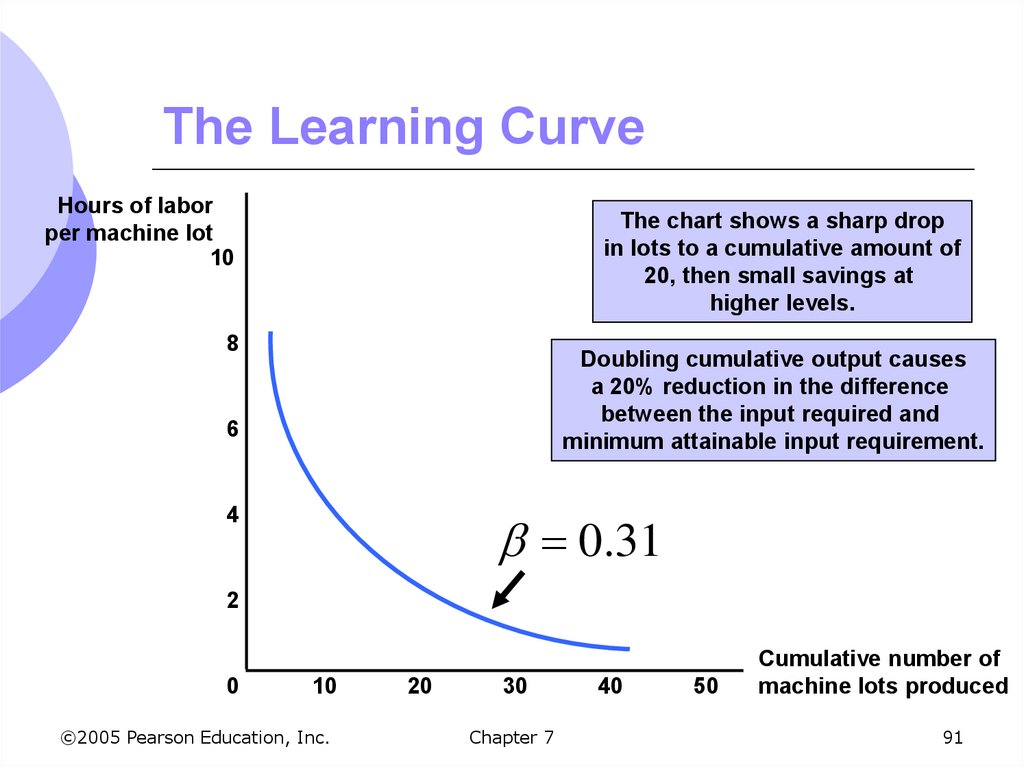

91. The Learning Curve

Hours of laborper machine lot

10

The chart shows a sharp drop

in lots to a cumulative amount of

20, then small savings at

higher levels.

8

Doubling cumulative output causes

a 20% reduction in the difference

between the input required and

minimum attainable input requirement.

6

0.31

4

2

0

10

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

20

30

Chapter 7

40

50

Cumulative number of

machine lots produced

91

92. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

Observations1. New firms may experience a learning curve,

not economies of scale

Should increase production of many lots

regardless of individual lot size

2. Older firms have relatively small gains from

learning

Should produce their machines in very large

lots to take advantage of lower costs

associated with size

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

92

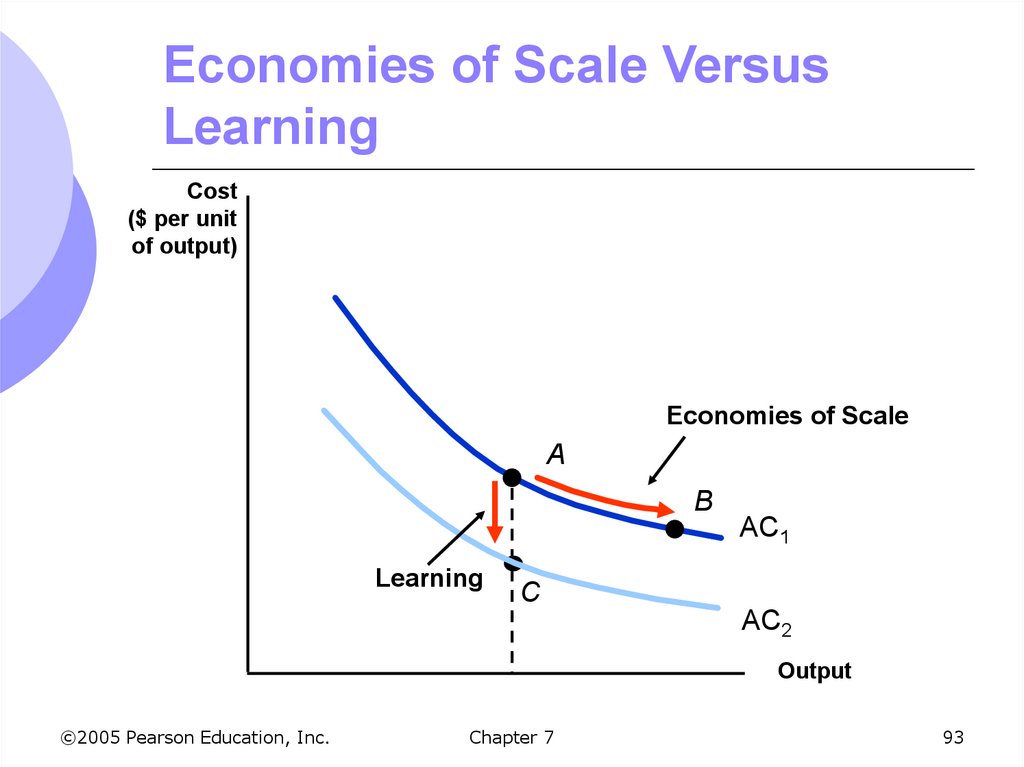

93. Economies of Scale Versus Learning

Cost($ per unit

of output)

Economies of Scale

A

B

Learning

AC1

C

AC2

Output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

93

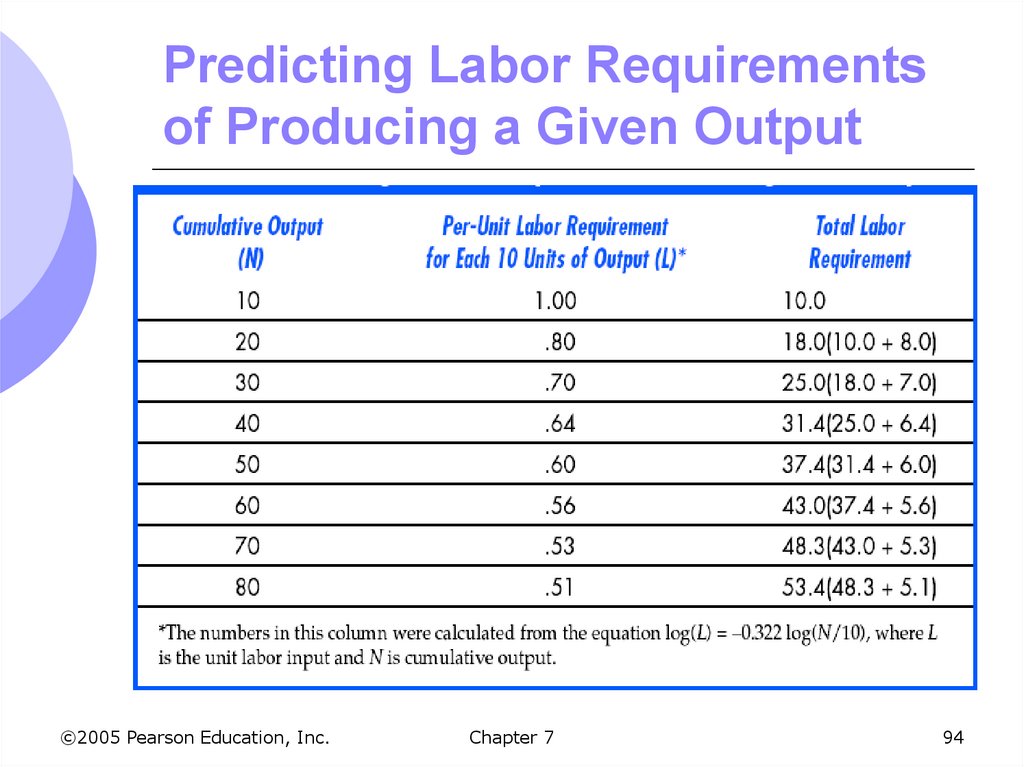

94. Predicting Labor Requirements of Producing a Given Output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.Chapter 7

94

95. Dynamic Changes in Costs – The Learning Curve

From the table, the learning curveimplies:

1. The labor requirement falls per unit

2. Costs will be high at first and then will fall

with learning

3. After 8 years, the labor requirement will be

0.51 and per unit cost will be half what it

was in the first year of production

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

95

96. The Learning Curve in Practice

ScenarioA new firm enters the chemical processing

industry

Do they:

1. Produce a low level of output and sell at a

high price?

2. Produce a high level of output and sell at a

low price?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

96

97. The Learning Curve in Practice

The Empirical FindingsStudy of 37 chemical products

Average cost fell 5.5% per year

For each doubling of plant size, average

production costs fall by 11%

For each doubling of cumulative output, the

average cost of production falls by 27%

Which is more important, the economies

of scale or learning effects?

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

97

98. The Learning Curve in Practice

Other Empirical FindingsIn the semiconductor industry, a study of

seven generations of DRAM semiconductors

from 1974-1992 found learning rates

averaged 20%

In the aircraft industry, the learning rates are

as high as 40%

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

98

99. The Learning Curve in Practice

Applying Learning Curves1. To determine if it is profitable to enter an

industry

2. To determine when profits will occur based

on plant size and cumulative output

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

99

100. Estimating and Predicting Cost

Estimates of future costs can be obtainedfrom a cost function, which relates the

cost of production to the level of output

and other variables that the firm can

control

Suppose we wanted to derive the total

cost curve for automobile production

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

100

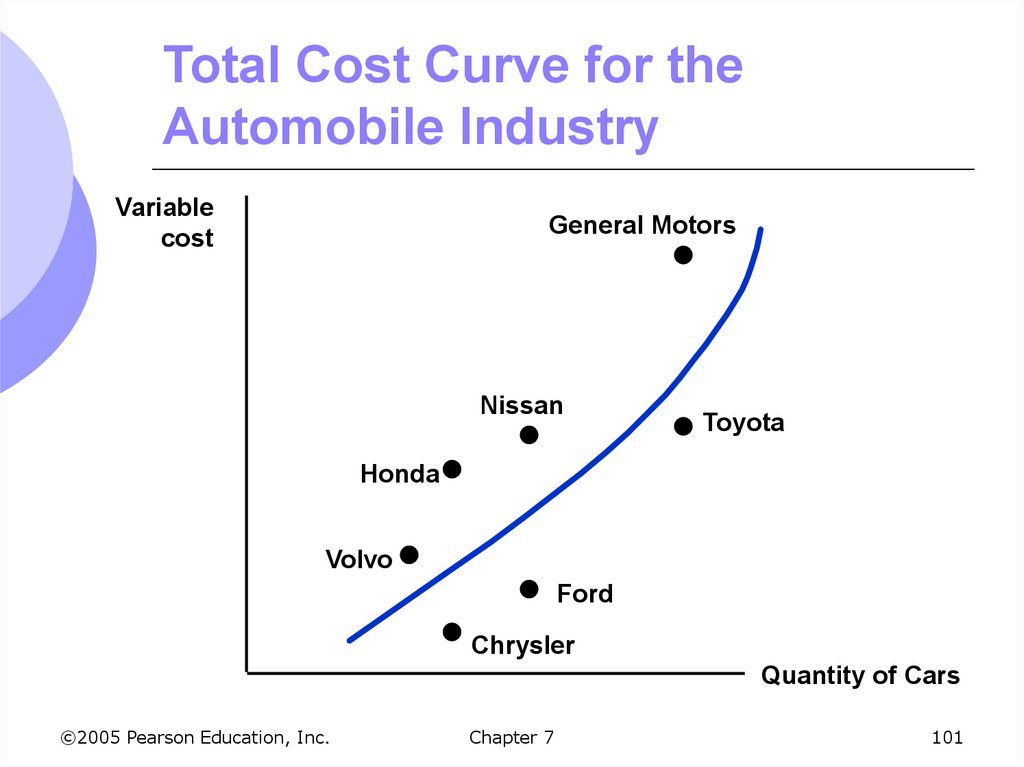

101. Total Cost Curve for the Automobile Industry

Variablecost

General Motors

Nissan

Toyota

Honda

Volvo

Ford

Chrysler

Quantity of Cars

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

101

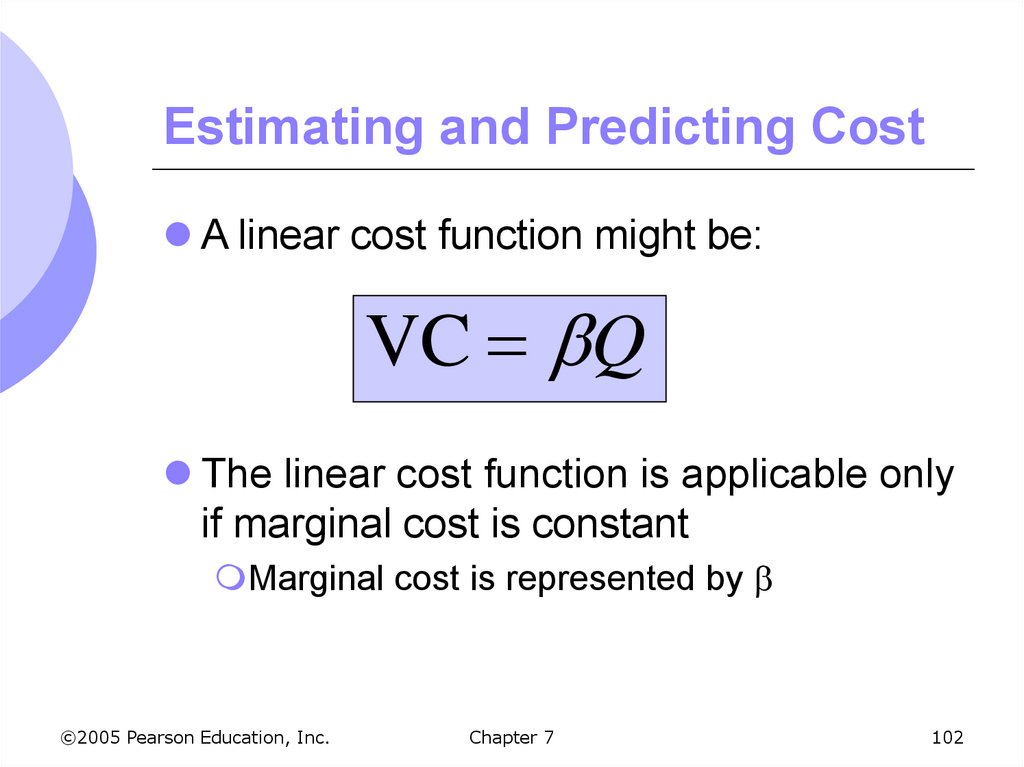

102. Estimating and Predicting Cost

A linear cost function might be:VC Q

The linear cost function is applicable only

if marginal cost is constant

Marginal cost is represented by

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

102

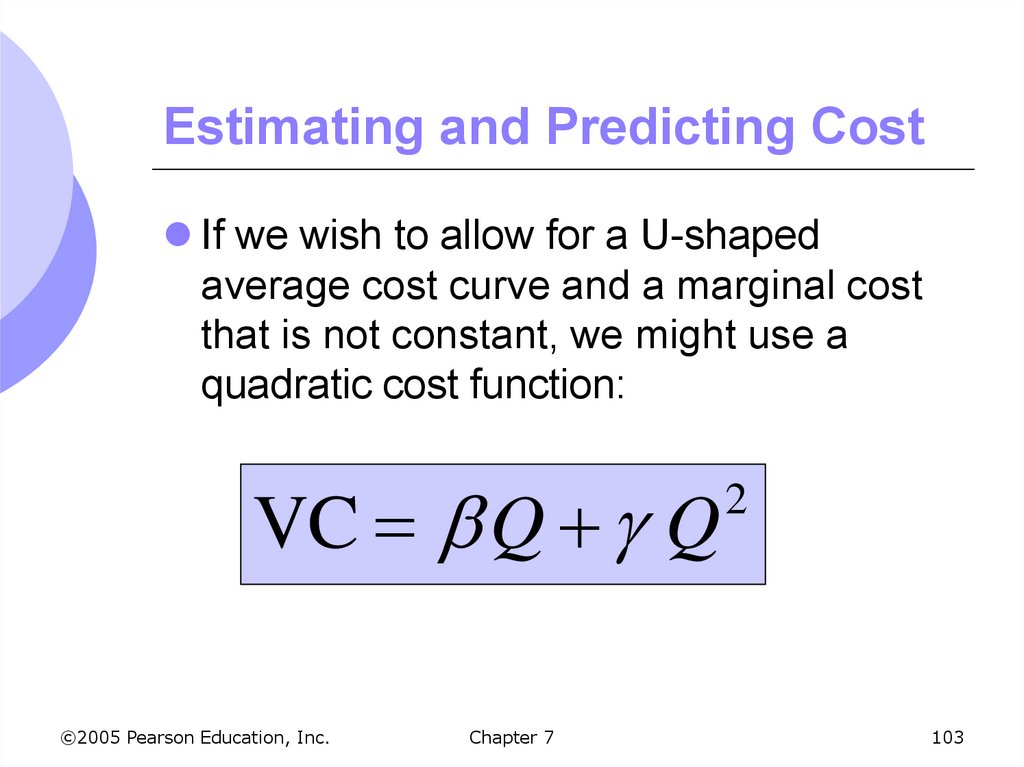

103. Estimating and Predicting Cost

If we wish to allow for a U-shapedaverage cost curve and a marginal cost

that is not constant, we might use a

quadratic cost function:

VC Q Q

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

2

103

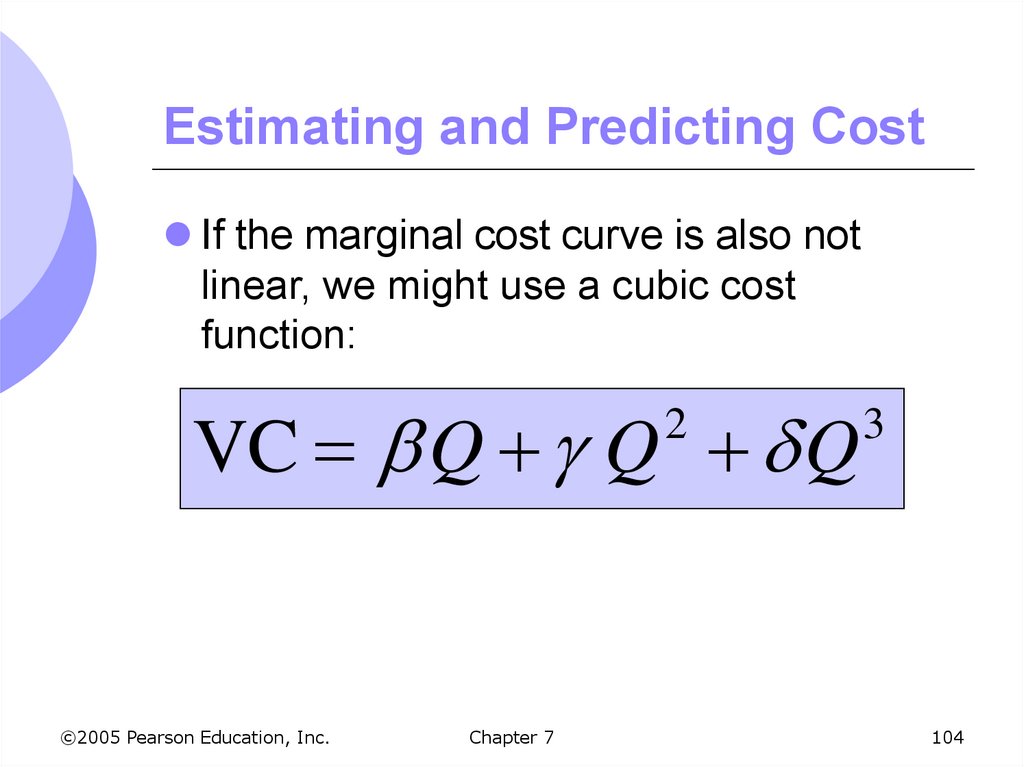

104. Estimating and Predicting Cost

If the marginal cost curve is also notlinear, we might use a cubic cost

function:

VC Q Q Q

2

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

3

104

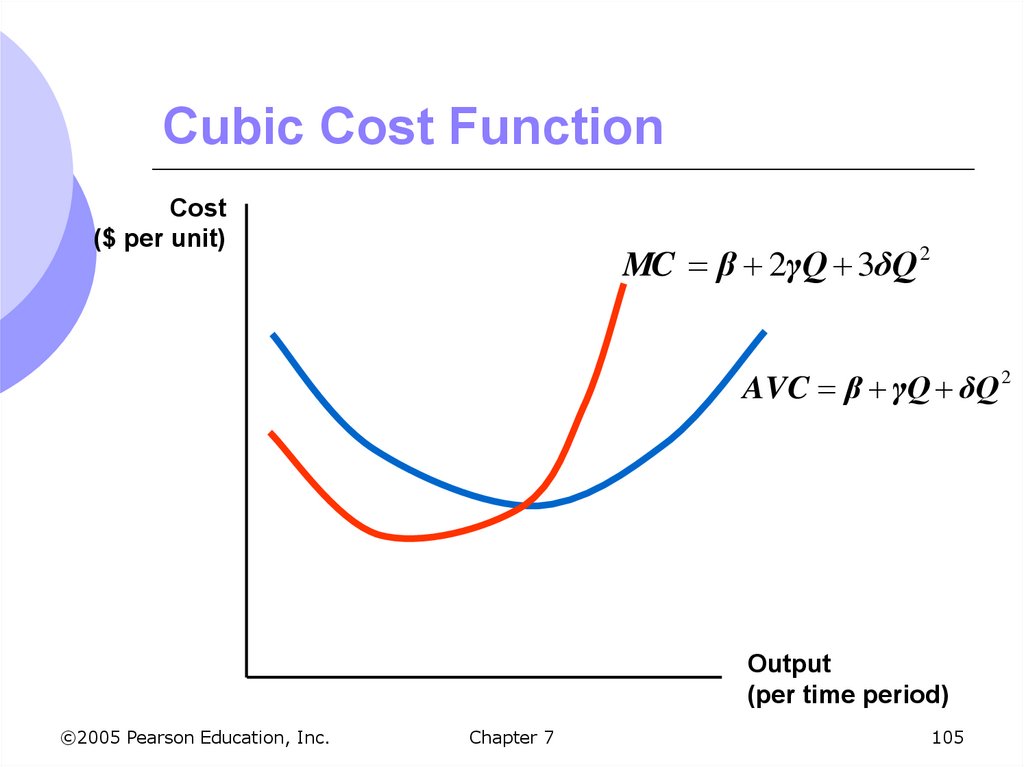

105. Cubic Cost Function

Cost($ per unit)

MC β 2γQ 3δQ 2

AVC β γQ δQ 2

Output

(per time period)

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

105

106. Estimating and Predicting Cost

Difficulties in Measuring Cost1. Output data may represent an aggregate of

different types of products

2. Cost data may not include opportunity cost

3. Allocating cost to a particular product may

be difficult when there is more than one

product line

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

106

107. Cost Functions & Measurement of Scale Economies

Cost Functions & Measurementof Scale Economies

Scale Economy Index (SCI)

EC = 1, SCI = 0: no economies or

diseconomies of scale

EC > 1, SCI is negative: diseconomies of

scale

EC < 1, SCI is positive: economies of scale

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

107

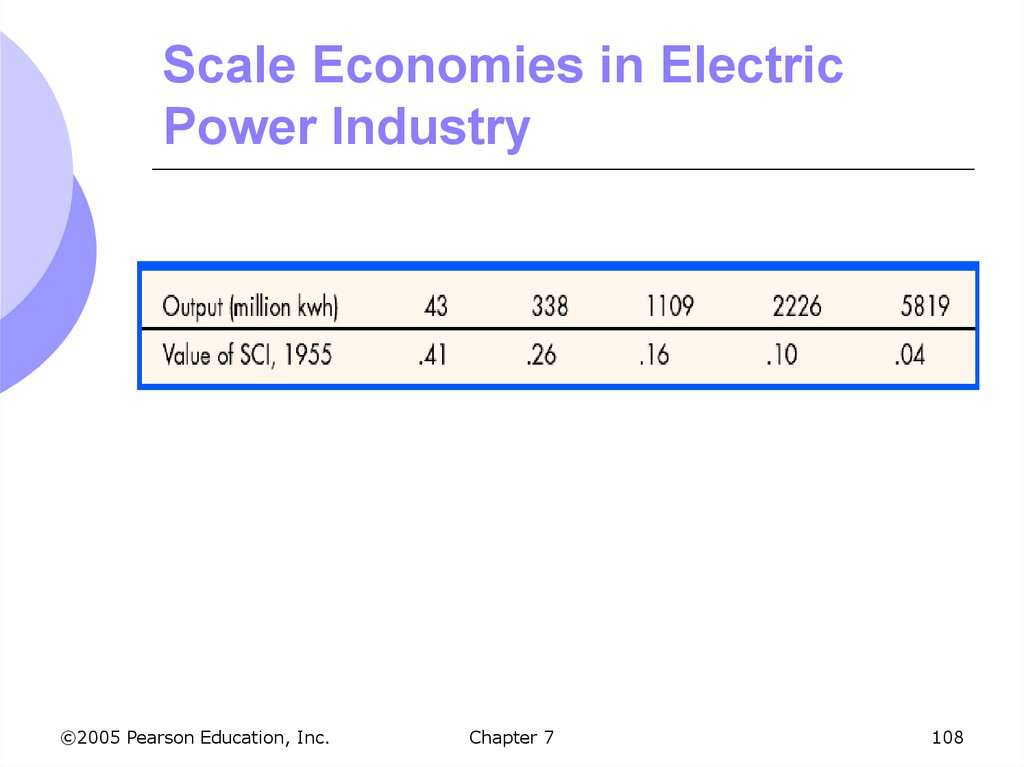

108. Scale Economies in Electric Power Industry

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.Chapter 7

108

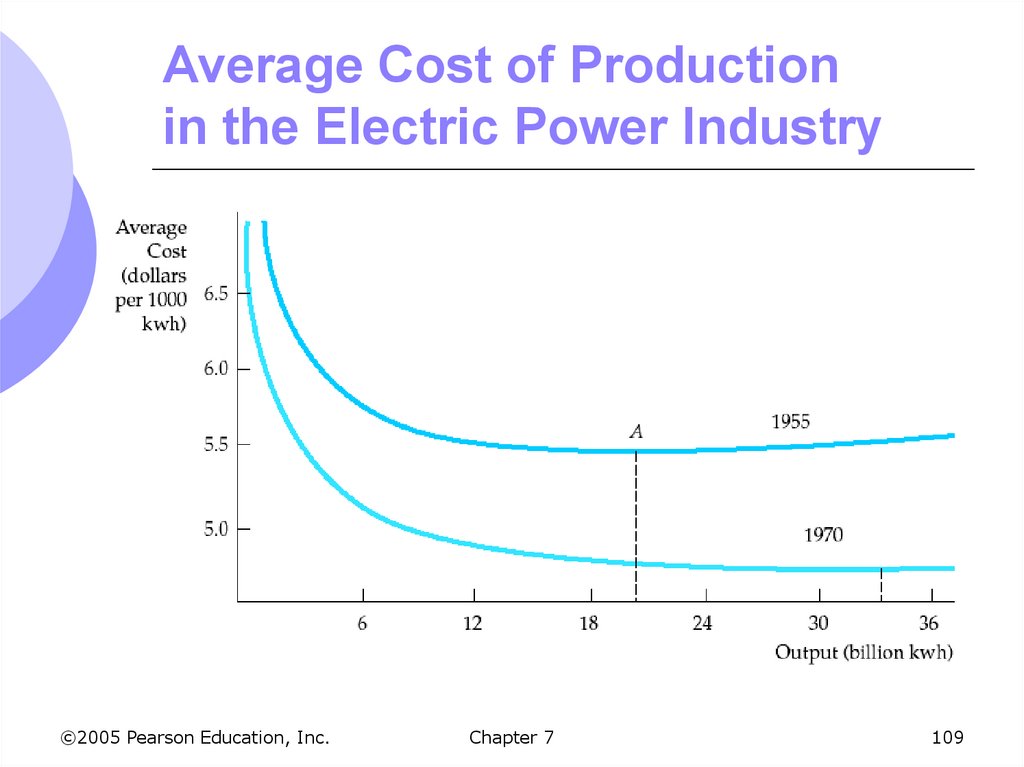

109. Average Cost of Production in the Electric Power Industry

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.Chapter 7

109

110. Cost Functions for Electric Power

FindingsDecline in cost

Not due to economies of scale

Was caused by:

Lower input cost (coal and oil)

Improvements in technology

©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 7

110

economics

economics