Similar presentations:

Abnormalities of the expulsive forces

1.

ABNORMALITIES OFTHE EXPULSIVE FORCES

2.

Types of UterineDysfunction

• Uterine contractions are needed to dilate the cervix and to

expel the fetus.

• A contraction is initiated by spontaneous action potentials

in the membrane of smooth muscle cells.

• Unlike the heart, a single pacemaker or its site remain

unresolved.

• Resulting uterine contractions in normal labor show a rising

and falling gradient of myometrial activity.

• Normal spontaneous contractions can exert pressures

approximating 60 mmHg .

• Even so, the lower limit of contraction pressure required to

dilate the cervix is 15 mmHg.

3.

Types of UterineDysfunction

• In abnormal labor, two physiological types of uterine

dysfunction may develop.

• In the more common hypotonic uterine dysfunction,

basal tone is normal and uterine contractions have a

normal gradient pattern (synchronous).

• However, pressure during a contraction is insufficient

to dilate the cervix.

• In the second type, hypertonic uterine dysfunction or

incoordinate uterine dysfunction, either basal tone is

elevated appreciably or the pressure gradient is

distorted.

4.

Risk Factors for UterineDysfunction

• Various factors are implicated in uterine

dysfunction.

• First, neuraxial analgesia can slow labor and has

been associated with longer first and second

stages of labor.

• With current anesthesia methods, however, its

effect on labor length is blunted.

5.

Risk Factors for UterineDysfunction

• Chorioamnionitis is associated with prolonged labor.

• Uterine infection may directly contribute to uterine

dysfunction or instead may simply be an associated

consequence of prolonged, dysfunctional labor.

• Affected gravidas are monitored for labor progress, and

augmentation of protracted labor is prudent.

6.

Risk Factors for UterineDysfunction

• A higher station at the onset of labor is

significantly linked with subsequent dystocia.

• Although a risk factor, most nulliparas without

fetal head engagement at diagnosis of active

labor still deliver vaginally.

• These observations apply especially for parous

women because the head typically descends later

in labor.

7.

Risk Factors for UterineDysfunction

• Dystocia rate rises proportionally with maternal age even

after adjusting for maternal and fetal weight and parity.

• Maternal obesity lengthens the first stages of labor by 30 to

60 minutes in nulliparas, even after adjusting for associated

diabetes, fetal weight, and parity.

• Dystocia-associated cesarean delivery rates are higher in

this group.

• Growing evidence suggests a pathologic biological effect of

obesity on normal parturition.

8.

Labor Disorders9.

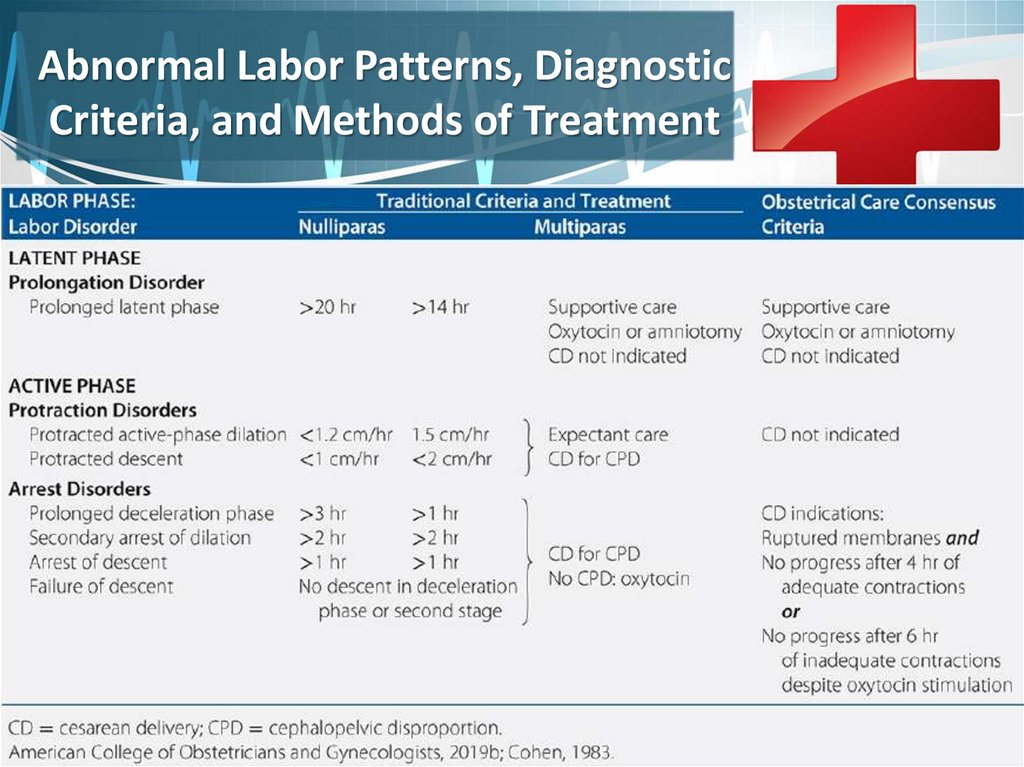

Abnormal Labor Patterns, DiagnosticCriteria, and Methods of Treatment

10.

Latent-phase Prolongation• Uterine dysfunction can in turn lead to labor abnormalities.

• First, the latent phase may be prolonged, which is defined

as >20 hours in the nullipara and >14 hours in the

multipara.

• In some, uterine contractions cease, suggesting false labor.

• In the remainder, an abnormally long latent phase persists

and is often treated with amniotomy and oxytocin

stimulation.

• The diagnosis of uterine dysfunction in the latent phase is

difficult and commonly is made retrospectively.

• Women who are not yet in active labor often are

erroneously treated for perceived uterine dysfunction.

11.

Active-phase Disorders• In active labor, disorders are divided into

those with slow progress — a protraction

disorder or those with halted progress — an

arrest disorder.

• Terms presented in table and their diagnostic

criteria describe abnormal labor.

• To be diagnosed with either of these, a

woman must be in the active phase of labor.

12.

Active-phase Protraction• Of active-phase disorders, protraction disorders are less well

described.

• Previously, protraction has been defined as <1 cm/hr cervical

dilation for a minimum of 4 hours.

• For this disorder, observation for further progress is appropriate

treatment.

• In monitoring active labor, if hypotonic contractions are strongly

suspected, internal monitors may be placed with amniotomy and

again cervical change and contraction pattern are reassessed.

• Deficient Montevideo units and poor active labor progress typically

prompts oxytocin augmentation.

• Slow but progressive first-stage labor should not be an indication

for cesarean delivery.

13.

Montevideo units• To assess uterine activity, many methods have been

proposed, based on a complex mathematical

assessment of the duration of contractions, their

intensity and frequency over a certain period of time

(usually 10 minutes).

• The most widespread assessment of uterine activity is

in Montevideo units (MU).

• Montevideo units are the product of the contraction

intensity and the frequency of uterine contractions in

10 minutes.

• Normally, uterine activity increases as labor progresses

and amounts to 150-300 MU.

14.

15.

Active-phase Arrest• Handa and Laros (1993) diagnosed active-phase arrest, defined as

no dilation for ≥2 hours, in 5 percent of term nulliparas.

• Inadequate uterine contractions, defined as <180 Montevideo

units, were diagnosed in 80 percent of women with active-phase

arrest.

• Hauth and coworkers (1986, 1991) reported that when labor is

effectively induced or augmented with oxytocin, 90 percent of

women achieve 200 to 225 Montevideo units, and 40 percent

achieve at least 300 Montevideo units.

• These results suggest that certain minimums of uterine activity

should be achieved before performing cesarean delivery for

dystocia.

• Oxytocin regimens suitable to augment labor mirror those to induce

labor.

16.

Active-phase Arrest• Other criteria should also be met.

• First, the latent phase should be completed, and

the cervix is dilated ≥4 cm.

• Also, a uterine contraction pattern of ≥200

Montevideo units in a 10-minute period has been

present for ≥4 hours without cervical change

(Rouse, 1999).

• The Consensus Committee has extended this

further, as described next.

17.

Obstetric CareConsensus Committee

• The Obstetric Care Consensus series are

documents jointly developed with the Society

for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) with

The American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists (ACOG) (a professional

association of physicians specializing in

obstetrics and gynecology in the United

States).

18.

Obstetric CareConsensus Committee

• Four recommendations of the Consensus

Committee apply to management of firststage labor.

• The first admonishes against cesarean delivery

in the latent phase.

• Specifically, a prolonged latent phase should

not be the sole indication for cesarean

delivery.

19.

Obstetric CareConsensus Committee

• The second directive, too, is conventional

practice.

• It recommends against cesarean delivery if

labor is progressive but slow—a protraction

disorder.

• This instance is typically managed with

observation, assessment of uterine activity,

and stimulation of contractions as needed.

20.

Obstetric CareConsensus Committee

• A third instruction addresses the cervical dilation

threshold that serves to herald active labor.

• Namely, a cervical dilation of 6 cm—not 4 cm—is

now the recommended threshold.

• Moreover, before this threshold, standards for

active-phase progress should not be applied.

• Of note, the WHO (2018) recognizes 5 cm as the

active-labor threshold.

• Other large studies noted labor acceleration after

5 cm (Ashwal, 2020; Oladapo, 2018).

21.

Obstetric CareConsensus Committee

• A fourth stipulation notes that cesarean

delivery for active-phase arrest is best

reserved for women with cervical dilation ≥6

cm and ruptured membranes who fail to

progress despite 4 hours of adequate uterine

activity or despite at least 6 hours of oxytocin

administration but inadequate contractions.

22.

Cervical dilation curves fromFriedman (1955) and Zhang (2002).

23.

Second-stage DescentDisorders

• Fetal descent largely follows complete

dilation.

• Moreover, the second stage incorporates

many of the cardinal movements necessary

for the fetus to negotiate the birth canal.

• Thus, disproportion of the fetus and pelvis

frequently becomes apparent during secondstage labor.

24.

Second-stage DescentDisorders

• Similar to first-stage labor, time boundaries have been

supported to limit second-stage duration to minimize

adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

• The second stage in nulliparas has been limited to 2

hours and extended to 3 hours when regional analgesia

is used.

• For multiparas, 1 hour has been the limit, extended to

2 hours with regional analgesia.

• However, of maternal outcomes, higher rates of

chorioamnionitis, anal sphincter injury, operative

vaginal birth, and postpartum hemorrhage accrue as

the second stage lengthens.

25.

Second-stage DescentDisorders

• Newer guidelines have been promoted by the Consensus

Committee (2019b) for second-stage labor.

• These recommend that a nullipara push for at least 3 hours and a

multipara push for at least 2 hours before second-stage labor arrest

is diagnosed.

• Importantly, one caveat is that maternal and fetal status should be

reassuring.

• These authors provide options to these times before cesarean

delivery is performed.

• Namely, longer durations may be appropriate as long as progress is

documented.

• Also, a specific maximal length of time spent in second-stage labor

beyond which all women should undergo operative delivery has not

been identified.

26.

Maternal Pushing Efforts• With full cervical dilation, most women cannot resist the urge to push with

uterine contractions.

• The combined force created by contractions of the uterus and abdominal

musculature propels the fetus downward.

• However, at times, force created by abdominal musculature is

compromised sufficiently to slow or even prevent spontaneous vaginal

delivery.

• Heavy sedation or regional analgesia may reduce the reflex urge to push

and may impair the ability to contract abdominal muscles sufficiently.

• Allowing time for these to abate is reasonable.

• In other instances, the urge to push is overridden by the intense pain

created by bearing down.

• Depending on fetal station and anticipated second stage, options include

emotional support and encouragement, parenteral analgesia, pudendal

blockade, or neuraxial analgesia.

27.

Oxytocin• As previously emphasized, in many instances, preinduction

cervical ripening and labor induction are simply a

continuum.

• In this regard “ripening” can also stimulate labor.

• If not, induction or augmentation may be continued with

solutions of oxytocin given by infusion pump.

• Its use in augmentation is a key component in the active

management of labor.

• With oxytocin use, the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists (2019a) recommends fetal heart rate

and uterine contraction monitoring.

• Contractions can be monitored either by palpation or by

electronic means.

28.

Oxytocin• preparation of solution: for intravenous

administration with a perfuser - 1 ml (5 IU) in 49

ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution.

• Administration schemes:

• Low-dose infusion – starting dose 3 mU/min – 1.8

ml/hour (“step” – 1.8 ml/hour)

• High-dose infusion – starting dose 6 mU/min –

3.6 ml/h (“step” – 3.6 ml/h)

29.

Oxytocin• Increase the rate of oxytocin administration

every 20-30 minutes by 1 “step” until 4-5

contractions are achieved in 10 minutes/

• The monitoring of the condition of the mother

and fetus, then fix this minimally effective

dose.

• 33 mU/min (19.8 ml/hour) is an extremely

dangerous level.

30.

Oxytocin• If there is no effect from the administration of

Oxytocin:

• lack of labor and dynamics of cervical

dilatation within 3-5 hours

• inability to reach the active phase of labor

within 5-15 hours

• - resolve the issue of delivery by CS surgery.

medicine

medicine