Similar presentations:

Morphological analysis for health care systems planning

1.

MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS FOR HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS PLANNING

RICHARD E. TUBLEY, WILLIAM C. RICHARDSON* and JAMES V. HANSENt

Departmentof Mechanical Engineering, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S.A.

(Receiued 16April 1974)

Abstract-Health care planners are continually challenged by the difficulty of ordering and understanding of the

complexities of health care delivery systems. Methods are needed which can aid in extending thought processes into

multi-dimensional solution space and rationalizing the thinking of various health care interests. This paper describes

a useful approach to designing and evaluating health care systems utilizing a case study of a large metropolitan

community.

represented as a horizontal relevance tree. The vertical

axis enumerates individual parts or functions of the

system. The horizontal axis describes the available and

anticipitated subdimensions.

Morphological analysis may be applied at nearly any

level of aggregation. It may, for example, be used to

investigate alternative methods of designing a public

health system, a preventive care program, or a health

maintenance organization (HMO). The approach is

basically the same for each of these objectives.

An important advantage of the morphological method is

its formal approach to discovering and examining solution

alternatives. It forces the planner to work systematically

from “morphological space”, which reflects the known,

into nearby space, which is not known. A typical

procedure is to vary the parameters of the initial

conhguration one at a time keeping the others fixed as the

examination moves into the unknown region[5].

Another advantage of this technique centers on its total

enumeration approach. It provides a means of examining

all possible configurations which may be appropriate to a

given objective. This process often reveals gaps in

required services (or technology) and forces the analyst to

include alternatives which might otherwise be overlooked

or summarily dismissed as being infeasible. Under closer

examination, combinations having the superficial appearance of absurdity may turn out to be viable alternativesor they may suggest modifications which will promote

viability. Zwicky, for example, ultimately identified or

invented fourteen new telescope designs as the result of

preparing a lecture on the morphological method applied

to telescope design[3].

There are, of course, limitations to the morphological

method. One is that it is limited to existing technologiesalthough it can prove valuable in pointing up areas of

needed technologies. Another constraint is that the

analysts must have a thorough knowledge of the field to

which it is being applied. The use of a team of experts can

generally improve the quality and completeness of

solution alternatives.

The first step in constructing the morphological space is

to formulate the problem to be investigated. The narrower

the scope of problem definition, the less complex will be

the subsequent analysis. The second step is to select the

dimensions upon which the attainment of the objective

depends. Next, elements which represent alternatives at

each level are identified as entries or vertices of the tree.

The fourth step is to establish sets of criteria for each of

the levels. Finally, applications of methods drawn from

Health care planners are frequently confronted with the

problem of assessing current system effectiveness, and

developing and evaluating alternatives for meeting health

care needs. This is a particularly difficult task as modern

day health care has become a highly complex system

having numerous components whose relationships are not

generally well understood[l]. Further, major changes in

the arrangements for the delivery of personal health

services have been occurring in recent years, and many

policy questions have arisen as a consequence. Several

substantive problem areas appear to be of particular

concern in the present process of public policy reformulation. These problems include: the types of care rendered

and its continuity, the evenness of access opportunities

across various segments of the population, the utilization

of scarce manpower, and finally, the structuring and

consequences of existing incentives within the health

field. Because proposed solutions within any of these

areas impact other problem areas in complex ways,

increasing attention has been focused on development

and evaluation of diverse health care delivery modes[2].

In order to cope with the need for innovation in the face

of increasing complexity, methods need to be developed

and applied which can upgrade our ability to extend our

thinking into multi-dimensional solution space.

MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

One approach which can facilitate this type of thinking

is morphological analysis. This methodology, formulated

more than two decades ago by Fritz Zwicky [3,4] has not

received wide attention despite his efforts to promote its

application to technological and social problems. The

general objective of morphological analysis is to visualize

all possible solutions to any given problem and to point

the way toward the general performance evaluation of

these solutions. The methodology is based on graph

theory with the morphological space representing a graph

consisting of dimensions which are sets of nodes

representing parameters. If the morphological space

consists of two dimensions it may be expressed as- a

matrix. If it consists of three dimensions it may be

expressed as a box. An n-dimensional space is best

*School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University

of Washington U.S.A.

TPacbic Northwest Laboratories, Battelle Memorial Institute

Richland, Washington 99352,U.S.A.

83

2.

RICHARDE. TURLEY, WILLIAMC. RICHARDSON

and JAMESV. HANSEN

a4

systems analysis and operations research may be utilized

to order the analysis into a logical framework.

A MORPHOLOGY

OF HEALTH CARE DELIYERY

The authors were recently engaged in a study of health

care delivery in a large metropolitan community with the

objectives of assessing the current system’s effectiveness

and developing and evaluating alternatives for meeting

community health care needs. The impetus for this

research derived from a group of concerned community

health care providers who felt that unmet health care

needs existed in the community and that its health care

resources could be utilized more effectively.

Subsequent investigations supported this concern. In

particular, it was determined that a double standard of

health care was being perpetuated in the community. The

individual or family adequately insured or able to pay for

health care was able to exercise freedom in choosing a

provider. Freedom of choice for the poor was, however,

greatly limited. As a consequence, the poor felt rejected

by the county system of health care. While access to the

nongovernmental system was restricted, the poor were

concerned that even if barriers to access were removed

there would be no assurance that they would receive the

same level of treatment and consideration as the

non-poor.

Preliminary analysis suggested that much of the

problem could be eliminated if a means could be found to

pay providers adequately for their services, while at the

same time encouraging

the establishment

of

patient-physician relationships between the poor and

primary care practitioners. This prompted the need for a

framework for thinking about the problem which would

enhance the prospects for developing a sound solutionone which would (1) be operationally feasible, (2) meet the

unsatisfied health care needs of the cornunity, and (3)

receive support from community providers and recipients

of health care, as well as government agencies and the

community at large.

It was clearly evident that in order to promote

development of such a solution there was need for an

approach which would: (1) minimize the possibility of

overlooking an important combination of system dimensions; and (2) help in organizing and directing the thinking

of community health care providers, as well as those

whose cooperation would be necessary for any concept to

be successfully implemented. Morphological analysis

appeared to offer a framework which would facilitate

meeting this need.

DESIGN

Alternatives were derived using five primary dimensions and their associated subdimensions. The subdimension, “Other”, was used to include dimensions not

considered critical to the analysis.

Major dimensions of the system which were of concern

were determined to be the following:

1.O Patient

2.0 Type of care needed

3.0 Organizational base for services

4.0 Ownership

5.0 Provider reimbursement

These major dimensions along with their respective

subdimensions are outlined below and shown in morphological form in Fig. 1.

1.0 Patient: The patient was designated either as (1.1)

Private pay or Insured, or as (1.2) Medically indigent.

2.0 Type of care needed: Three levels of care were

considered as the major subdimensions applicable to the

study. These types of care were as follows: (2.1) Primary,

(2.2) Specialty, (2.3) Inpatient, and another subdimension

was added, (2.4) Other, as a catch-all for any other

conceived type.

3.0 Organizational base for services: Five primary

subdimensions were used to further break down the

organizational base for delivery of the care as described

under major dimension (2.0). These were as follows: (3.1)

Physician’s office, (3.2) Primary ambulatory health care

center, (3.3) Primary-specialty hospital outpatient department, (3.4) Specialty outpatient clinic, and (3.5) Hospital.

The set was left open by adding (3.6) Other.

4.0 Ownership: For the purposes of analysis, ownership of organizations or facilities was classified as either:

(4.1) Nongovernmental, or (4.2) Governmental. It may be

possible, of course, to have a governmental facility

operated by a nongovernmental organization and vice

versa.

5.0 Provider reimbursement: Reimbursement to the

provider was divided broadly into two general categories:

(5.1) Open market fee-for service, and (5.2) Contracted

services. Under the subdimension (5.2) were included

contracted services, either on a capitation basis or a feefor-service basis.

Fig. 1. Dimensions used to derive alternatives for health delivery system.

3.

Morphologicalanalysisfor healthcare systemsplanningSELECTEDSYSTEMALTERNATIVES

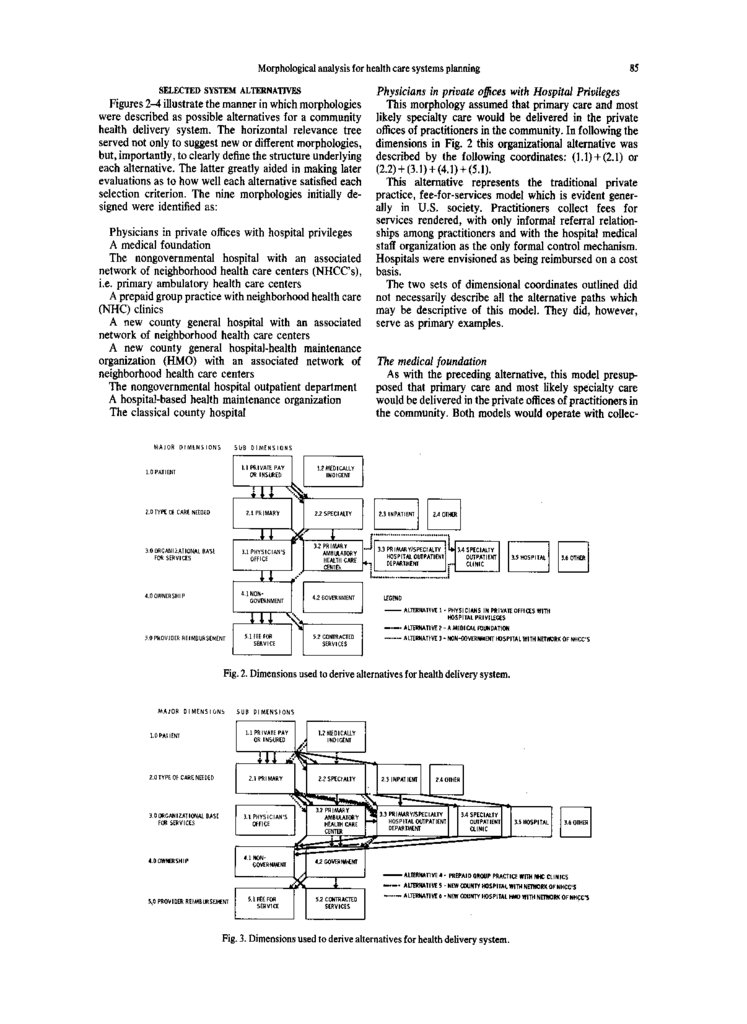

Figures 2-4 illustrate the manner in which morphologies

were described as possible alternatives for a community

health delivery system. The horizontal relevance tree

served not only to suggest new or different morphologies,

but, importantly, to clearly define the structure underlying

each alternative. The latter greatly aided in making later

evaluations as to how well each alternative satisfied each

selection criterion. The nine morphologies initially designed were identified as:

Physicians in private offices with hospital privileges

A medical foundation

The nongovernmental hospital with an associated

network of neighborhood health care centers (NHCC’s),

i.e. primary ambulatory health care centers

A prepaid group practice with neighborhood health care

(NHC) clinics

A new county general hospital with an associated

network of neighborhood health care centers

A new county general hospital-health maintenance

organization (HMO) with an associated network of

neighborhood health care centers

The nongovernmental hospital outpatient department

A hospital-based health maintenance organization

The classical county hospital

85

Physicians in private o&es with Hospital Privileges

This morphology assumed that primary care and most

likely specialty care would be delivered in the private

offices of practitioners in the community. In following the

dimensions in Fig. 2 this organizational alternative was

described by the following coordinates: (1.1)+ (2.1) or

(2.2)+(3.1)+(4.1)+(5.1).

This alternative represents the traditional private

practice, fee-for-services model which is evident generally in U.S. society. Practitioners collect fees for

services rendered, with only informal referral relationships among practitioners and with the hospital medical

staff organization as the only formal control mechanism.

Hospitals were envisioned as being reimbursed on a cost

basis.

The two sets of dimensional coordinates outlined did

not necessarily describe all the alternative paths which

may be descriptive of this model. They did, however,

serve as primary examples.

The medical foundation

As with the preceding alternative, this model presupposed that primary care and most likely specialty care

would be delivered in the private offices of practitioners in

the community. Both models would operate with collec-

4.0 OWNERSHIP

Fig. 2. Dimensionsusedto derivealternativesfor healthdeliverysystem.

Fig. 3. Dimensionsused to derivealternativesfor healthdeliverysystem.

4.

86RICHARD

E. TURLEY,WILLIAM

C. RICHARDSON

and JAMES

V. HANSEN

Fig.4. Dimensionsused to derivealternativesfor healthdeliverysystem.

tion on a capitation basis, but in the latter payment to both

primary and specialty physicians generally would be on a

prorated fee-for-services basis under contractural arrangements. There would also be contractual relatronships with local hospitals.

This morphology assumed a dual system of provider

reimbursement, i.e. patients having the option of paying

the customary fee-for-services and being free to enter and

leave the system, or patients enrolling to receive care

through contracted services. The dimensional coordinates

from Fig. 2 were the same as in the case of the

physician in his private office, except that the subdimension (5.2) was added.

The nongovernmental hospital with NHCC’s

The third alternative was identified as the nongovem-

mental hospital with an associated network of primary

ambulatory health care centers or neighborhood health

care centers. This model was characterized by a primary

ambulatory care center, or centers, located in the

community and operated under voluntary nongovernmental auspices. This was a three-level-of-care model with the

primary care delivered in the

* borhood and the

specialty care not necessarily prov

?Zh ed nearby but at a

related hospital. Physicians in the NHCC would have

privileges on the staff of the nongovernmental hospital

and follow their patients into the hospital as a consequence. Physicians in the NHCC would be organized as a

group and paid on a negotiated basis. Revenues received

by the NHCC would be generated from contracts for

selected populations and from fee-for service reimbursement.

One of the coordinate sets which describes this

alternative was (1.1)+(2.1)+(3.2)+(4.1)+(5.1)+or

(5.2)

(Fig. 2).

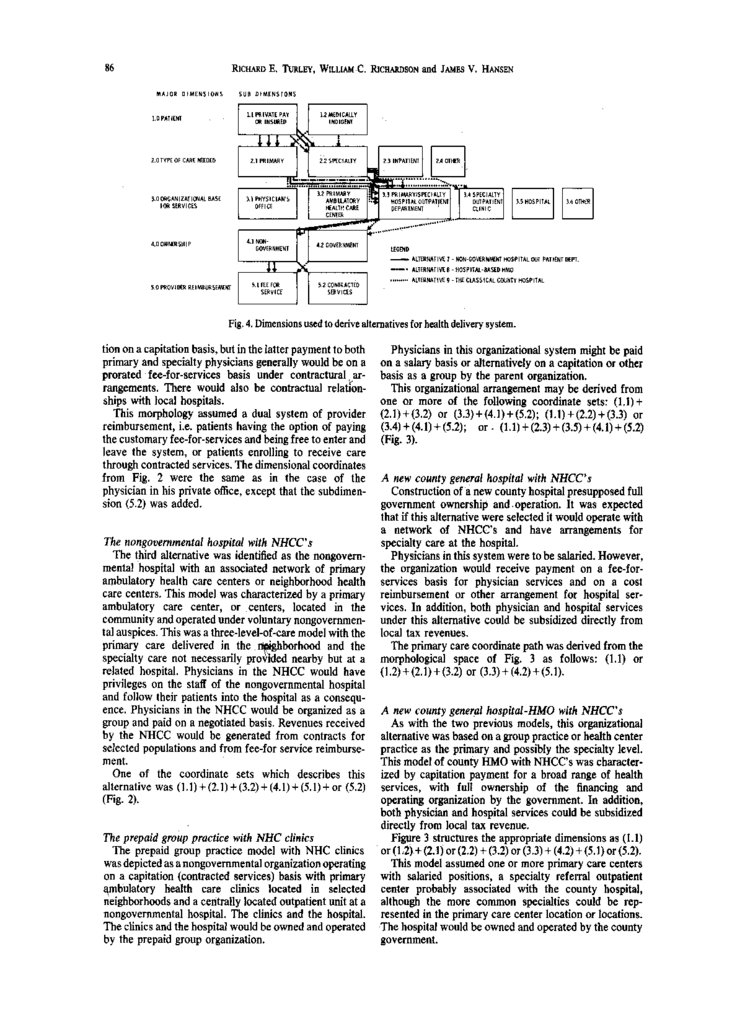

The prepaid group practice with NHC clinics

The prepaid group practice model with NHC clinics

was depicted as a nongovernmental organization operating

on a capitation (contracted services) basis with primary

ambulatory health care clinics located in selected

neighborhoods and a centrally located outpatient unit at a

nongovernmental hospital. The clinics and the hospital.

The clinics and the hospital would be owned and operated

by the prepaid group organization.

Physicians in this organizational system might be paid

on a salary basis or alternatively on a capitation or other

basis as a group by the parent organization.

This organizational arrangement may be derived from

one or more of the following coordinate sets: (1.1)+

(2.1)+(3.2) or (3.3)+(4.1)+(5.2); (l.l)t(2.2)+(3.3)

or

(3.4) + (4.1)t (5.2); or . (1.1)t (2.3) t (3.5) t (4.1) t (5.2)

(Fig. 3).

A new county general hospital with NHCC’s

Construction of a new county hospital presupposed full

government ownership and. operation. It was expected

that if this alternative were selected it would operate with

a network of NHCC’s and have arrangements for

specialty care at the hospital.

Physicians in this system were to be salaried. However,

the organization would receive payment on a fee-forservices basis for physician services and on a cost

reimbursement or other arrangement for hospital services. In addition, both physician and hospital services

under this alternative could be subsidized directly from

local tax revenues.

The primary care coordinate path was derived from the

morphological space of Fig. 3 as follows: (1.1) or

(1.2) t(2.1)+(3.2)

or (3.3)+(4.2)+(5.1).

A new county genecal hospital-HMO

with NHCC’s

As with the two previous models, this organizational

alternative was based on a group practice or health center

practice as the primary and possibly the specialty level.

This model of county HMO with NHCC’s was characterized by capitation payment for a broad range of health

services, with full ownership of the financing and

operating organization by the government. In addition,

both physician and hospital services could be subsidized

directly from local tax revenue.

Figure 3 structures the appropriate dimensions as (1.1)

or (1‘2)t (2.1) or (2.2) t (3.2) or (3.3) t (4.2) t (5.1) or (5.2).

This model assumed one or more primary care centers

with salaried positions, a specialty referral outpatient

center probably associated with the county hospital,

although the more common specialties could be represented in the primary care center location or locations.

The hospital would be owned and operated by the county

government.

5.

a7Morphological analysis for health care systems planning

The nongovernmental hospital outpatient department

This organizational alternative was hospital based. The

coordinates from Fig. 4 which trace the morphology of

this organizational arrangement are as follows: (l.l)t

(2.1) or (2.2) t (3.3) + (4.1) t (5.1).

The expanded nongovernmental outpatient department

exemplifies this alternative. Physicians would be reimbursed on a fee-for services basis or under negotiated

contract with the hospital.

A hospital-based HMO

This alternative was described as an organization

operated by a nongovernmental hospital on a capitation

basis. Physicians would serve as salaried employees of

the hospital. The organizational arrangement was derived

from the following coordinates as shown in Fig. 4:

(1.1) t (2.1) or (2.2)t (3.3)

t (4.1) t (5.1) or (5.2).

The classical county hospital

This alternative was the classical county hospital

model, with the entire operation owned and conducted by

local county government. Physicians in this model would

be on salary, and the organization reimbursed on a cost

basis to include physician services. In addition, the

hospital could be subsidized directly from local tax

revenues. The set of coordinates which describes the

system is graphed in Fig. 4 as follows: (1.1) or (1.2) t (2.1)

or (2.2)t (3.3) or (3.4) + (4.2) + (5.1).

RESULTS

Evaluation based upon predetermined criteria identified

the preferred morphologies as: (2) a medical foundation

(Fig. 2), (3) the nongovernmental hospital with NHCC’s

(Fig. 2), (4) a prepaid group practice with NHC clinics

(Fig. 3), and (8) a hospital-based HMO (Fig. 4).

An iterative assessment of the top-ranked alternatives

suggested that no one of them could by itself meet the

total health care needs of the community. For example,

Alternative 8 would require an unacceptable length of

time to implement. Alternative 4 as a single choice was

not viewed as being sufficient since the vast majority of

physicians in the community were currently in private

practice, and it became increasingly evident that any

viable system would have to include elements of

Alternative 1.

Utilizing the morphological space once again, a tenth

alternative was formulated drawing from the mor-

phologies of Alternatives 1, 2 and 3. Figure 5 illustrates

the health care system recommended for implementation

in the community. Under this morphology physicians

would continue to practice in their private offices, while

retaining privileges on the medical staff of one or more of

the nongovernmental hospitals. A medical foundation

would be established which would explore the possibility

of contracting with the county and state to take care of

certain segments of the population on a contracted

services or capitation basis. The individuals covered

under such an arrangement would either be the entire

categorical group in an agreed upon geographical area, or

a random selection of such patients to insure an

acceptable underwriting risk. The medical society of the

community would form the nucleus for such a foundation.

The society would set up a separate organization or other

acceptable alternative as the administrative agency for the

foundation. The more physicians participating in the

foundation, the more likely that suitable arrangements

could be made with the county or state.

The foundation would reimburse the physicians on a

fee-for-services basis. Immediately upon billing, the

physician would receive partial payment of his fee based

upon a maximum fee schedule. At the end of an agreed

upon fiscal period, the remainder of the fee would be

prorated or paid in full depending upon the fiscal

soundness of the program. Surplus funds could be set

aside as reserves for future underwriting losses or for

broadening the benefit program.

The medically indigent would also be treated by the

foundation, provided that a satisfactory arrangement

could be made with the county to serve their needs.

DISCUSSION

I The authors’ experience in assisting health care planners

suggests that a major obstacle to effective planning is the

inability to cope with the complexities of the health care

system. This tends to stifle creativity and to foster

dogmatism, and is a particularly severe problem in health

care delivery because of the number of special interests

involved. Tools to facilitate communication among these

interests and to aid in rational thinking are badly needed.

In this study, it was especially important that health care

experts representing the various interests have the

opportunity to suggest solutions or innovations from their

particular point of view. The morphological framework

provided a useful vehicle for subsequent analysis. First,

6.

88RICHARDE. TURLEY, WILLIAM

C. RICHARDSON

and JAMESV. HANSEN

the expert could readily determine whether all the

dimensions he perceived as being relevant were represented. Second, his suggestions for systems configurations could be quickly understood and analyzed by others.

Both of these processes stimulated rigorous discussions

which often produced new alternative structures.

It was another of the researchers’ objectives that no

important alternative be overlooked. While there is no

surety that this was accomplished, the range of alternatives considered (as well as modifications thereof) was

well beyond that which had been proposed initially.

Additionally, since the structure of each alternative

system was clearly defined, evaluations as to how well

each one satisfied the selection criteria was more easily

rationalized by the group. This was evidenced by several

preliminary evaluations which were unable to be supported under close examination of the structure and intent

of the particular alternative.

Finally, the numerous interations through the morphological graph generated the thinking which resulted in

the recommended alternative.

CONCLUSION

Many of the most pressing problems of our society lie

unsolved or partially solved because of our limited ability

to extend our thinking into a multidimensional solution

space. As a tool for stimulating ideas, morphological

analysis represents a useful approach to invention,

discovery, and innovation. Devices or ideas in a set

representing the state-of-the-art may be reduced to their

basic parameters and these parameters categorized to

establish the dimensions of morphological space. These

may, in turn, be expanded by adding other appropriate

parameters. The best combination of parameters may be

suggested through the application of elements of graph

theory and decision theory.

REFFBENCFS

1. William J. Horvath, The systems approach to the national

health problem, Mgmt Sci. 12, B391-B395(1966).

2. Richard E. Turley, William C. Richardson and James V.

Hansen, A morphological approach to designing and evaluating

health care systems. Proc. Fifth Nat. Meeting Am. Inst.

Decision Sci. (1973).

3. Fritz Zwicky, Discovery, Invention, Research. Macmillan, New

York (1%9).

4. A. G. Wilson and F. Zwicky, MorphologicalResearch. Springer,

New York (1967).

5. Robert U. Ayres, Technological Forecasting and Long-Range

Planning.McGraw-Hill,New York (1969).

medicine

medicine