Similar presentations:

Morphology. Word formation rule

1.

MORPHOLOGYWORD FORMATION RULE

2.

MORPHEME• Linguists define a morpheme as the smallest

unit of language that has its own meaning.

3.

WORDA word can be defined as one or more

morphemes that can stand alone in a

language.

4.

• We each have a mental lexicon, a sort ofinternalized dictionary that contains an

enormous number of words that we can

produce, or at least understand when we

hear them. But we also have a set of word

formation rules which allows us to create

new words and understand new words when

we encounter them.

5.

• Each person’s mental lexicon is sure to containthings that are different from other people’s

mental lexicons. One person may know lots of

words for types of birds or flowers, another

might know all the specialized vocabulary of

sailing, and so on. But our individual mental

lexicons overlap enough that we speak the

same language.

6.

• Psycholinguists estimate that the averageEnglish-speaking six-year-old knows 10,000

words, and the average high-school graduate

around 60,000 words.

• Psycholinguists calculate that between the

ages of one and 18 we would have to learn

approximately ten words every day to have a

vocabulary of 60,000 words.

7.

The organization of the mental lexicon: storage versusrules.

• The mental lexicon is not organized

alphabetically like a dictionary. Rather, it is a

complex web composed of stored items

(morphemes, words, idiomatic phrases) that

may be related to each other by the sounds that

form them and by their meanings. Along with

these stored items we also have rules that

allow us to combine morphemes in different

ways.

8.

• It is the rules of word formation that we knowthat most distinguish our mental lexicon from

the dictionary. The dictionary does not need

to list all the words that we know or that we

could create, because once we know word

formation rules we can produce and

understand potentially infinite numbers of

new words from the morphemes available to

us.

9.

Affixation• Prefixes and suffixes usually have special

requirements for the sorts of bases they can

attach to. Some of these requirements

concern the phonology (sounds) of their

bases, and others concern the semantics

(meaning) of their bases, but the most basic

requirements are often the syntactic part of

speech or category of their bases.

10.

• The prefix un- attaches to adjectives (where itmeans ‘not’) and to verbs (where it means

‘reverse action’), but not to nouns:

• a. un- on adjectives: unhappy, uncommon,

unkind, unserious

b. un- on verbs: untie, untwist, undress,

unsnap

c. un- on nouns: *unchair, *unidea,

*ungiraffe

11.

• The suffix -ness attaches to adjectives, as theexamples in (a) show, but not to verbs or nouns

(b–c):

• a. -ness on adjectives: redness, happiness,

wholeness, commonness,

• niceness

• b. -ness on nouns: *chairness, *ideaness,

*giraffeness

• c. -ness on verbs: *runness, *wiggleness,

*yawnness

12.

• Challenge• Look at the following words and try to work out

more details of the rule for un- in English. The (a)

list contains some adjectives to which negative

un- can be attached and others which seem

impossible. The (b) list contains some verbs to

which un- can attach and others which seem

impossible. See if you can discern some patterns:

• (a) unhappy, *unsad, unlovely, *unugly,

unintelligent, *unstupid

• (b) untie, unwind, unhinge, unknot, *undance,

*unyawn, *unexplode, *unpush

13.

• The negative prefix un- in English prefers toattach to bases that do not themselves have

negative connotations. This is not true all of

the time – adjective like unselfish is attested in

English – but it’s at least a significant

tendency.

• The un- that attaches to verbs prefers verbal

bases that imply some sort of result, and

moreover that the result is not permanent.

14.

• A word formation rule:a rule which makes explicit all the categorial,

semantic, and phonological information that native

speakers know about the kind of base that an affix

attaches to and about the kind of word it creates.

• The full word formation rules for negative un-:

rule for negative un- (final version): un- attaches to

adjectives,

preferably those with neutral or

positive connotations, and creates negative

adjectives. It has no phonological restrictions.

15.

Word structure• When you divide up a complex word into its

morphemes, it’s easy to get the impression that

words are put together like the beads that make

up a necklace – one after the other in a line:

Unhappiness = un+happy+ness

But morphologists believe that words are more like

onions than like necklaces: onions are made up of

layers from innermost to outermost.

16.

• Challenge• In English, the suffix -ize attaches to nouns or

adjectives to form verbs. The suffix -ation attaches to

verbs to form nouns. And the suffix -al attaches to

nouns to form adjectives. Interestingly, these suffixes

can be attached in a recursive fashion: convene →

convention → conventional → conventionalize →

conventionalization.

See if you can find other bases on which you can attach

these suffixes recursively. What is the most complex

word you can create from a single base that still

makes sense to you? Are there any limits to the

complexity of words derived in this way?

17.

• Languages frequently have affixes that fall intocommon semantic categories. Among those

categories are:

• personal affixes: These are affixes that create

‘people nouns’ either from verbs or from

nouns. Among the personal affixes in English

are the suffix -er which forms agent nouns

(the ‘doer’ of the action) like writer or runner

and the suffix -ee which forms patient nouns

(the person the action is done to).

18.

• negative and privative (ˈprɪvətɪv) affixes:Negative affixes add the meaning ‘not’ to their

base; examples in English are the prefixes un-,

in- and non- (unhappy, inattentive, nonfunctional). Privative affixes mean something

like ‘without X’; in English, the suffix -less

(shoeless, hopeless) is a privative suffix, and

the prefix de- has a privative flavor as well (for

example, words like debug or debone mean

something like ‘cause to be without

bugs/bones’).

19.

• prepositionaland

relational

affixes:

Prepositional and relational affixes often

convey notions of space and/or time.

Examples in English might be prefixes like

over- and out- (overfill, overcoat, outrun,

outhouse).

20.

• quantitative affixes: These are affixes thathave something to do with amount. In English

we have affixes like -ful (handful, helpful) and

multi- (multifaceted). Another example might

be the prefix re- that means ‘repeated’ action

(reread), which we can consider quantitative if

we conceive of a repeated action as being

done more than once.

21.

• evaluative affixes: Evaluative affixes consist ofdiminutives (dɪˈmɪnjʊtɪv), affixes that signal a

smaller version of the base (for example in

English -let as in booklet or droplet) and

augmentatives (ɔːɡˈmɛntətɪv), affixes that

signal a bigger version of the base. The closest

we come to augmentative affixes in English

are prefixes like mega- (megastore, megabite).

22.

• https://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/word-formation/prefixes

• https://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/bri

tish-grammar/word-formation/suffixes

23.

• Infixation in EnglishEnglish doesn’t have any productive processes of infixation, but

there’s one marginal process that comes close. In colloquial

spoken English, we will often take our favorite taboo word or

expletive – in American English fucking, goddam, or frigging,

in British English bloody – and insert it into a base word:

• fan-bloody-tastic

• Ala-friggin’-bama

This kind of infixation is used to emphasize a word, to make it

stronger.

What’s particularly interesting is that we can’t insert fuckin just

anywhere in a word. In other words, there are phonological

restrictions.

(CAMBRIDGE INTRODUCTION TO MORPHOLOGY)

24.

INFLECTION• Morphology can be divided into two domains:

inflectional and derivational word formation.

• Inflection:

word formation process that

expresses a grammatical distinction.

• Inflection refers to word formation that does

not change category and does not create new

lexemes, but rather changes the form of

lexemes so that they fit into different

grammatical contexts.

25.

• Inflection in English26.

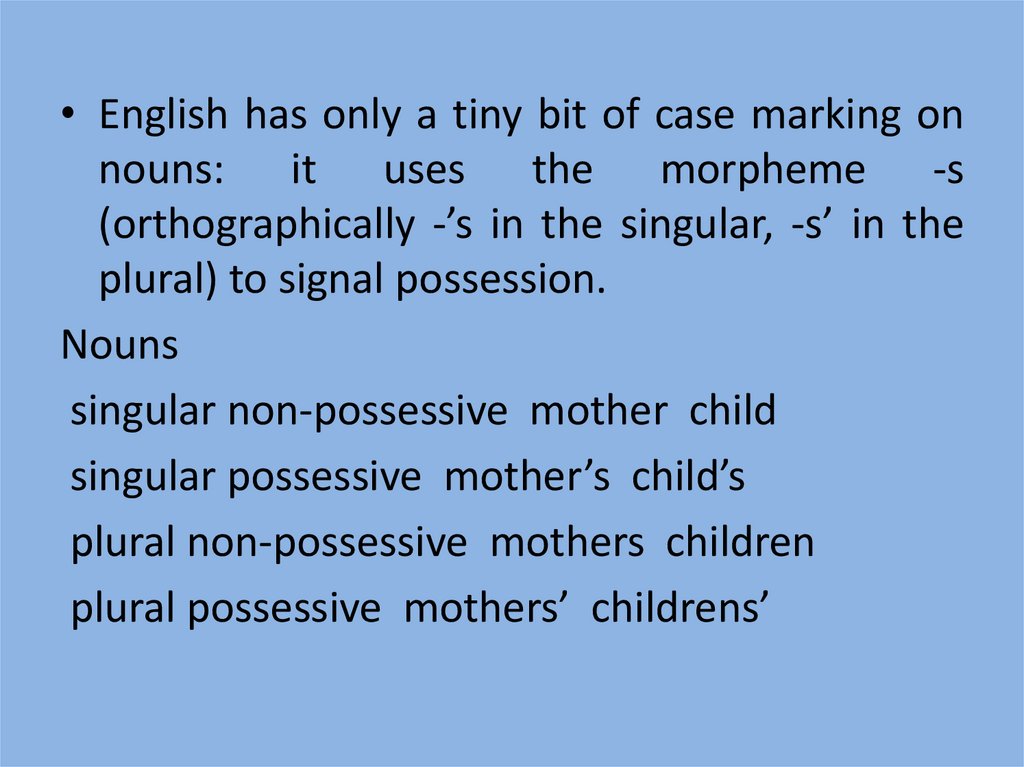

• English has only a tiny bit of case marking onnouns: it uses the morpheme -s

(orthographically -’s in the singular, -s’ in the

plural) to signal possession.

Nouns

singular non-possessive mother child

singular possessive mother’s child’s

plural non-possessive mothers children

plural possessive mothers’ childrens’

27.

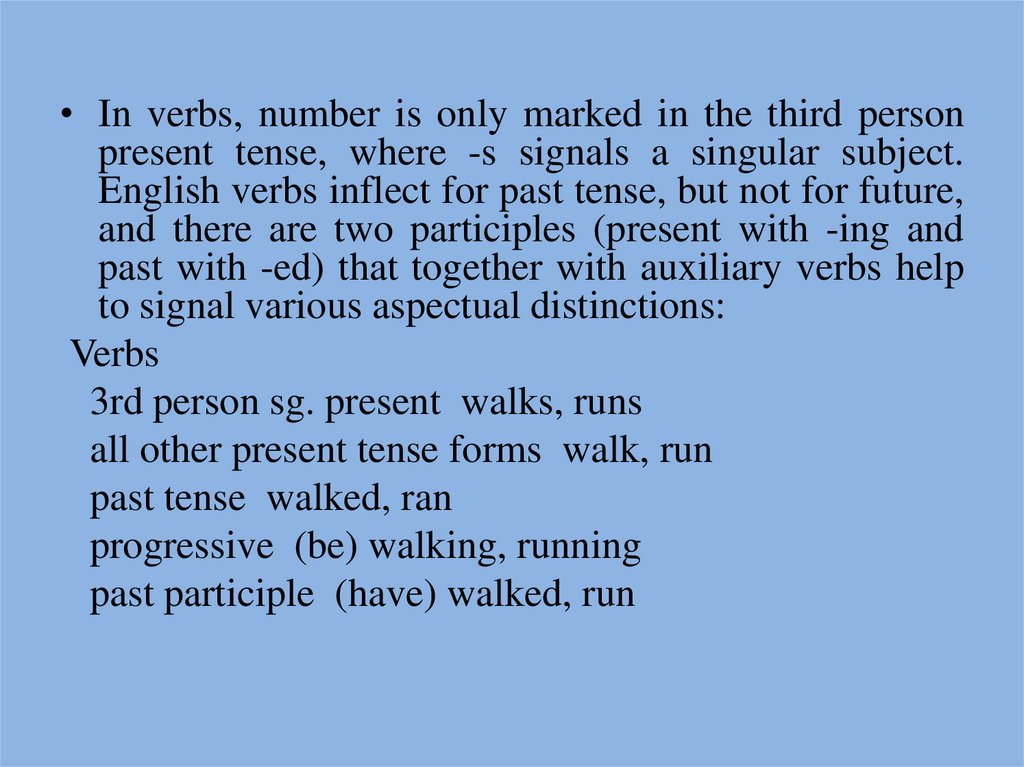

• In verbs, number is only marked in the third personpresent tense, where -s signals a singular subject.

English verbs inflect for past tense, but not for future,

and there are two participles (present with -ing and

past with -ed) that together with auxiliary verbs help

to signal various aspectual distinctions:

Verbs

3rd person sg. present walks, runs

all other present tense forms walk, run

past tense walked, ran

progressive (be) walking, running

past participle (have) walked, run

28.

Why English has so little inflection?29.

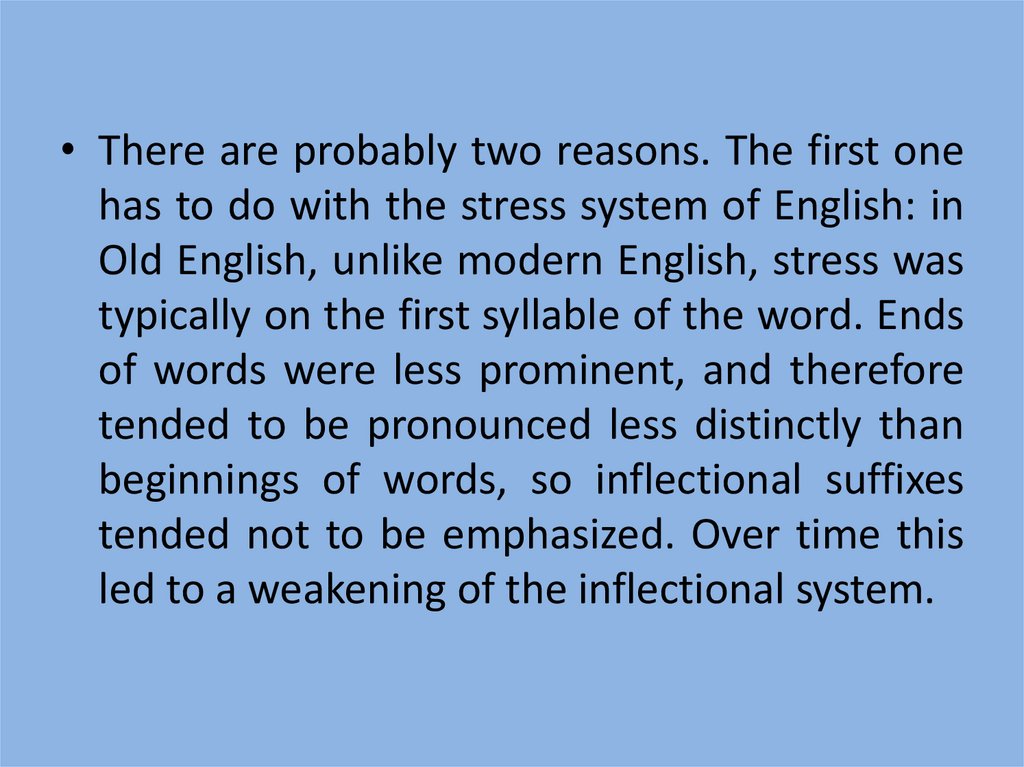

• There are probably two reasons. The first onehas to do with the stress system of English: in

Old English, unlike modern English, stress was

typically on the first syllable of the word. Ends

of words were less prominent, and therefore

tended to be pronounced less distinctly than

beginnings of words, so inflectional suffixes

tended not to be emphasized. Over time this

led to a weakening of the inflectional system.

30.

• Some scholars attribute the loss of inflectionto language contact in the northern parts of

Britain. For some centuries during the Old

English period, northern parts of Britain were

occupied by the Danes, who were speakers of

Old Norse. Old Norse is closely related to Old

English. The actual inflectional endings,

however, were different, although the two

languages shared a fair number of lexical

stems.

31.

Analogy• Sometimes new complex words are derived

without an existing word formation rule, but

formed on the basis of a single (or very few)

model words. For example, earwitness

‘someone who has heard a crime being

commited’ was coined on the basis of

eyewitness, cheeseburger on the basis of

hamburger, and air-sick on the basis of seasick. The process by which these words came

into being is called analogy.

32.

• Rochelle Lieber “Introducing Morphology”(Cambridge Introductions to Language and

Linguistics), 2009.

• Geert Booij “The Grammar of Words. An

Introduction to Linguistic Morphology “

(OXFORD TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS), 2005.

english

english