Similar presentations:

A healthy ocean

1.

QuotesEven if you never have a chance to see or

touch the ocean, the ocean touches you with

every breath you take, every drop you drink,

every bite you consume. Everyone,

everywhere is inextricably connected to and

utterly dependent upon the existence of the

sea.

Our oceans are the natural treasure upon which

marine and coastal resources and industries have

been able to flourish and which today represent

more than five percent of global GDP.

2.

A healthy ocean means a healthy planet!3.

Noise pollution 'drowns out ocean soundscape4.

Researchers say evidence of the harm ocean noisepollution can do has been building for decades

Noise from shipping, construction, sonar and

seismic surveys is "drowning out" the healthy

ocean soundscape, scientists say.

And an "overwhelming body of evidence" has

revealed the harm human-made noise does to

marine life.

"We've degraded habitats and depleted marine

species," said Prof Carlos Duarte, who led the study,

said.

"So we've silenced the soundtrack of the healthy

ocean and replaced it with the sound that we create."

5.

Sound is a fundamental cue"Sound is a fundamental cue for feeding, navigation, communication and

social interaction in the ocean," he told BBC News.

A great deal of the decades of research into ocean sound has focused on

marine mammals such as humpback whales that communicate across vast

distances with complex and mysterious songs.

But Prof Duarte said there was evidence even newly hatched fish larvae

were now unable to hear "the call of home" when drifting in the vast ocean.

"We now know that [these tiny larvae] hear the call from their habitat and

follow it," he said.

"And that call is no longer being heard."

Marine scientist Dr Heather Koldewey, from the Zoological Society of

London, said that the underwater realm was a "a cacophony of sound as

animals meet, greet, breed, and use noise in a variety of ways".

"It's is an important yet overlooked aspect of what constitutes a healthy

ocean," she added.

6.

The soundscape of even the most pristine oceanenvironments has been altered by human activity

7.

But the scientists pointed out that the globallockdown revealed how quickly and easily the

problem of noise pollution could be solved.

"Last year, when 60% of all humans were in

lockdown, the level of human noise [in the ocean]

reduced by about 20%," said Prof Duarte.

"That relatively modest reduction was enough for a

wave of observations.

"Large marine mammals - the easiest to observe were seen near coastlines and in waterways that

they'd not been seen in for generations."

8.

And this showed tackling this marine "anthrophony"was the "low-hanging fruit" of ocean health.

"If we look at climate change and plastic pollution,

it's a long and painful path to recovery," Prof Duarte

said.

"But the moment we turn the volume down, the

response of marine life is instantaneous and

amazing."

9.

An anthropogenic cacophonySound travels faster and farther in water than in air.

Over evolutionary time, many marine organisms

have come to rely on sound production,

transmission, and reception for key aspects of their

lives. These important behaviors are threatened by

an increasing cacophony in the marine environment

as human-produced sounds have become louder and

more prevalent. Duarte et al. review the importance

of biologically produced sounds and the ways in

which anthropogenically produced sounds are

affecting the marine soundscape.

10.

BACKGROUNDSound is the sensory cue that travels farthest through the

ocean and is used by marine animals, ranging from

invertebrates to great whales, to interpret and explore

the marine environment and to interact within and

among species. Ocean soundscapes are rapidly changing

because of massive declines in the abundance of soundproducing animals, increases in anthropogenic noise,

and altered contributions of geophysical sources, such as

sea ice and storms, owing to climate change. As a result,

the soundscape of the Anthropocene ocean is

fundamentally different from that of preindustrial times,

with anthropogenic noise negatively impacting marine

life.

11.

ADVANCESWe find evidence that anthropogenic noise negatively

affects marine animals. Strong evidence for such impacts

is available for marine mammals, and some studies also

find impacts for fishes and invertebrates, marine birds,

and reptiles. Noise from vessels, active sonar, synthetic

sounds (artificial tones and white noise), and acoustic

deterrent devices are all found to affect marine animals,

as are noise from energy and construction infrastructure

and seismic surveys. Although there is clear evidence that

noise compromises hearing ability and induces

physiological and behavioral changes in marine animals,

there is lower confidence that anthropogenic noise

increases the mortality of marine animals and the

settlement of their larvae.

12.

OUTLOOKAnthropogenic noise is a stressor for marine animals. Thus, we call

for it to be included in assessments of cumulative pressures on

marine ecosystems. Compared with other stressors that are

persistent in the environment, such as carbon dioxide emitted to the

atmosphere or persistent organic pollutants delivered to marine

ecosystems, anthropogenic noise is typically a point-source

pollutant, the effects of which decline swiftly once sources are

removed. The evidence summarized here encourages national and

international policies to become more ambitious in regulating and

deploying existing technological solutions to mitigate marine noise

and improve the human stewardship of ocean soundscapes to

maintain a healthy ocean. We provide a range of solutions that may

help, supported by appropriate managerial and policy frameworks

that may help to mitigate impacts on marine animals derived from

anthropogenic noise and perturbations of soundscapes.

13.

Changing ocean soundscapesThe illustrations from top to bottom show ocean soundscapes

from before the industrial revolution that were largely

composed of sounds from geological (geophony) and

biological sources (biophony), with minor contributions from

human sources (anthrophony), to the present Anthropocene

oceans, where anthropogenic noise and reduced biophony

owing to the depleted abundance of marine animals and

healthy habitats have led to impacts on marine animals. These

impacts range from behavioral and physiological to, in

extreme cases, death. As human activities in the ocean

continue to increase, management options need be deployed

to prevent these impacts from growing under a “business-asusual” scenario and instead lead to well-managed

soundscapes in a future, healthy ocean. AUV, autonomous

underwater vehicle.

14.

A healthy oceanOceans have become substantially noisier since the Industrial

Revolution. Shipping, resource exploration, and infrastructure

development have increased the anthrophony (sounds

generated by human activities), whereas the biophony

(sounds of biological origin) has been reduced by hunting,

fishing, and habitat degradation. Climate change is affecting

geophony (abiotic, natural sounds). Existing evidence shows

that anthrophony affects marine animals at multiple levels,

including their behavior, physiology, and, in extreme cases,

survival. This should prompt management actions to deploy

existing solutions to reduce noise levels in the ocean, thereby

allowing marine animals to reestablish their use of ocean

sound as a central ecological trait in a healthy ocean.

15.

Why This Year Is Our Last, Best Chance for Saving the OceansIn fact, the underwater realm sounds more like an orchestra warming up,

the cetaceans hitting their high notes while other marine mammals clear

their throats against a background of breaking waves. A distant downpour

sends out a staccato riff that can be heard for miles, even as fish and marine

invertebrates snap out a syncopated rhythm designed to scare off predators

or attract mates. It is a cacophonous soundscape that had changed little in

tens of thousands of years. Until, that is, modern humans brought their leaf

blowers to the concert hall.

Over the past couple of hundred years, humans have progressively altered

the ocean soundtrack with the introduction of shipping, industrial fishing,

coastal construction, oil drilling, seismic surveys, warfare, sea-bed mining

and sonar-based navigation. Until recently, underwater sound pollution

had not attracted the same attention as its terrestrial equivalent. Now, a

new paper published in the journal Science titled “Soundscape of the

Anthropocene Ocean” lays out the repercussions, demonstrating that noise

pollution can be just as harmful to the ocean environment as other kinds of

pollution.

16.

Human beings owe their life to the seaFour in 10 humans rely on the ocean for food. Marine

life produces 70% of our oxygen; 90% of global goods

travel via shipping lanes. We turn to the sea for solace—

ocean-based tourism in the U.S. alone is worth $124

billion a year—and medical advancement. An enzyme

used for COVID-19 testing was originally sourced from

bacteria found in the ocean’s hydro-thermal vents. The

ocean also acts as a giant planetary air conditioner. Over

the past century, the ocean has absorbed 93% of the heat

trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse-gas emissions.

“If all that heat hadn’t been taken up by the ocean, we’d

all be living in Death Valley conditions by now,” says

marine-conservation biologist Callum Roberts at the

U.K.’s University of York.

17.

a powerful part of the solutionA revitalized ocean would not only feed a growing population

but could also strengthen our fight against climate change.

Coastal habitats such as mangroves and salt marshes are

extraordinary carbon sinks, sequestering as much CO₂ per

acre as 16 acres of pristine Amazonian rain forest. New

developments in offshore wind-farm technology can provide

an inexhaustible supply of green energy, while mineral

deposits on the seafloor, if mined sustainably, offer the raw

ingredients for the batteries to store it. “It’s time to stop

thinking of the ocean as a victim of climate change and start

thinking of it as a powerful part of the solution,” says Jane

Lubchenco, a marine ecologist who served as head of the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

under President Barack Obama.

18.

The stakes for oceanThe stakes for ocean health have never been higher. The

dying kelp and disappearing coral reefs should be

sounding an urgent alarm, says Christopher Trisos, a

senior researcher at the African Climate and

Development Initiative at the University of Cape Town

who focuses on the inter-section of climate change,

biodiversity and human well-being. “Bio-diversity loss

from climate change looks like a trickle right now, but it

could become a flood very quickly,” he says. Even greater

“catastrophic multi-species die-offs” could begin within

the decade, Trisos predicts, starting with tropical oceans

and spreading to tropical forests and temperate

ecosystems by the 2050s.

19.

the ocean has an extraordinary ability to regenerate.But there are ways of preserving the ecosystems many

nations depend upon. Spanish-American marine

ecologist and conservationist Enric Sala has spent the

past 12 years surveying and documenting the ocean’s last

wilderness areas as a National Geographic explorer in

residence. Through his Pristine Seas project, he has

rallied governments to set aside 5.7 million sq km of

coastline and ocean as marine parks where fishing,

dumping, mining and other destructive industries are

prohibited. The results, he says, have been astonishing.

Even over a short time frame, he has watched depleted

fish populations grow sixfold, kelp flourish and coral

reefs bloom. Given the chance, he says, the ocean has an

extraordinary ability to regenerate.

20.

An international agreement to protect the oceanswould be a huge step—but it is only one tool, and an

expensive one. No amount of protection can block

pollution or plastic debris, or reduce temperatures.

Establishing marine protected areas is like taking an

aspirin for brain cancer, says Camilo Mora, a reefecology scientist at the University of Hawaii at

Manoa. “You think it’s working because the

headache goes away, but the tumor is still growing.

Unless we cut greenhouse-gas emissions, the threat

remains.”

21.

But the balance between sustainable use andconservation of the oceans is delicate, and sometimes

fraught with complications. Deep-sea mining in the

Pacific Ocean, for example, could yield massive increases

in cobalt, nickel, copper and other materials essential to

meet the demand for clean-energy technologies and

batteries. The U.N.’s International Seabed Authority is

expected this year to codify environmental-protection

codes before allocating permits for the extraction of socalled polymetallic nodules. But environmentalists and

marine biologists are calling for a moratorium on

permits until more research has been done on these

deposits and their role in the ecosystem.

22.

Why the Ocean MattersCovering 72 percent of the Earth and supplying half

its oxygen, the ocean is our planet's life support

system—and it’s in danger. Watch this video to learn

why a healthier ocean means a healthier planet, and

find out how you can help.

23.

With every breath we take, every drop we drink, we'reconnected to the ocean. Our planet depends on the vitality of

the ocean to support and sustain it. But our ocean faces major

threats: global climate change, pollution, habitat destruction,

invasive species, and a dramatic decrease in ocean fish

stocks. These threats to the ocean are so extensive that more

than 40 percent of the ocean has been severely affected and

no area has been left untouched. Consequently, humanity is

losing the food, jobs, and critical environmental services that a

healthy ocean generates. National Geographic Society's

Ocean Initiative aims to restore health and productivity to the

ocean by inspiring people to care and act, reducing

the impact of fishing, and promoting the creation of marine

protected areas.

24.

Explorer-in-Residencepre-eminent explorers and scientists collaborating

with the National Geographic Society to make

groundbreaking discoveries that generate critical

scientific information, conservation-related

initiatives and compelling stories.

25.

marine protected area (MPA)area of the ocean where a government has placed

limits on human activity.

26.

What does the ocean have to do with human health?Our ocean and coasts affect us all—even those of us

who don't live near the shoreline. Consider the

economy. Through the fishing and boating industry,

tourism and recreation, and ocean transport, one in

six U.S. jobs is marine-related. Coastal and marine

waters support over 28 million jobs. U.S. consumers

spend over $55 billion annually for fishery products.

Then there's travel and tourism. Our beaches are a

top destination, attracting about 90 million people a

year. Our coastal areas generate 85 percent of all

U.S. tourism revenues.

27.

Ocean in DistressWhen we think of public health risks, we may not think of the

ocean as a factor. But increasingly, the health of the ocean is

intimately tied to our health. One sign of an ocean in distress

is an increase in beach or shellfish harvesting closures across

the nation. Intensive use of our ocean and runoff from landbased pollution sources are just two of many factors that

stress our fragile ecosystems—and increasingly lead to human

health concerns. Waterborne infectious diseases, harmful

algal bloom toxins, contaminated seafood, and chemical

pollutants are other signals. Just as we can threaten the health

of our ocean, so, too, can our ocean threaten our health. And it

is not public health alone that may be threatened; our coastal

economies, too, could be at significant risk.

28.

Closing the Safety GapThroughout the U.S., there are thousands of beach and

shellfish closures or advisories each year due to the

presence of harmful marine organisms, chemical

pollutants, or algal toxins. To address public health

threats and benefits from the sea, NOAA scientists and

partners are developing and delivering useful tools,

technologies, and environmental information to public

health and natural resource managers, decision-makers,

and the public. These products and services include

predictions for harmful algal blooms and harmful

microbes to reduce exposure to contaminated seafood,

and early warning systems for contaminated beaches and

drinking water sources to protect and prevent human

illness.

29.

Emerging Health ThreatsWhales, dolphins, and other marine mammals eat much of the

same seafood that we consume, and we swim in shared coastal

waters. Unlike us, however, they are exposed to potential

ocean health threats such as toxic algae or poor water quality

24 hours a day, seven days a week. These mammals, and other

sentinel species, can shed important light on how the

condition of ocean environments may affect human health

now and in the future. As the principal stewardship agency

responsible for protecting marine mammals in the wild,

NOAA's Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

Program supports a network of national and international

projects aimed at investigating health concerns. This research

can not only warn us about potential public health risks and

lead to improved management of the protected species, but

may also lead to new medical discoveries.

30.

Cures from the DeepKeeping our ocean healthy is about more than

protecting human health—it's also about finding new

ways to save lives. The diversity of species found in

our ocean offers great promise for a treasure chest of

pharmaceuticals and natural products to combat

illness and improve our quality of life. Many new

marine-based drugs have already been discovered

that treat some types of cancer, antibiotic resistant

staph infections, pain, asthma, and inflammation.

31.

5 Ocean Terms You May Not Know — But Should!1. Tidal Bore

The name “tidal bore,” also called a “bore tide,” is a bit of

a misnomer — these natural occurrences are anything

but boring. Also called mascaret (French), pororoca

(Brazilian), and “the Bono” (Indonesian) — tidal bores

occur when the water in relatively shallow, sloping

estuaries or rivers moves as one massive solitary wave. In

order for a tidal bore to occur, the local tides must be

higher than average, and large amounts of water must be

concentrated as it flows down tight channels. Tidal bores

can reach up to 20 feet in height.

32.

This historic photograph shows a tidal bore in Turnagain Arm, awaterway that flows into Cook Inlet, Alaska.

33.

2. Hadal ZoneWant to hear something that’s really “deep?” The

ocean is made up of five “zones.” The hadalpelagic

zone, commonly known as the hadal zone, is the

deepest part of the ocean, with depths ranging from

approximately 6,096 meters to 10,973 meters

(20,000 feet to 36,000 feet). Named after the Greek

underworld Hades, the hadal zone is made up of a

series of trenches, troughs, and deep depressions.

The hadal zone remains one of the least investigated

and most mysterious places on Earth. More than 400

species are now known to live in the 21 trenches of

the hadal zone.

34.

Cusk eels (family Ophidiidae) are common in the deep sea, like this one of the genusLeucicorus.

35.

3. MixotrophyMost people think of life on Earth as being divided into

two categories: plants and animals. But that’s not always

the case. In the ocean, some single-celled, planktonic

algae, have the ability to photosynthesize like a plant and

consume other organisms like an animal. This hybrid

source of nutrition is called “mixotrophy.” A study from

NOAA’s National Ocean Service found that mixotrophic

algae may have an advantage in the formation of harmful

algal blooms — when algae grow out of control and

produce toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish,

marine mammals, and birds. The information from the

study will allow scientists to improve the models that

predict these dangerous occurrences.

36.

an example of mixotrophy37.

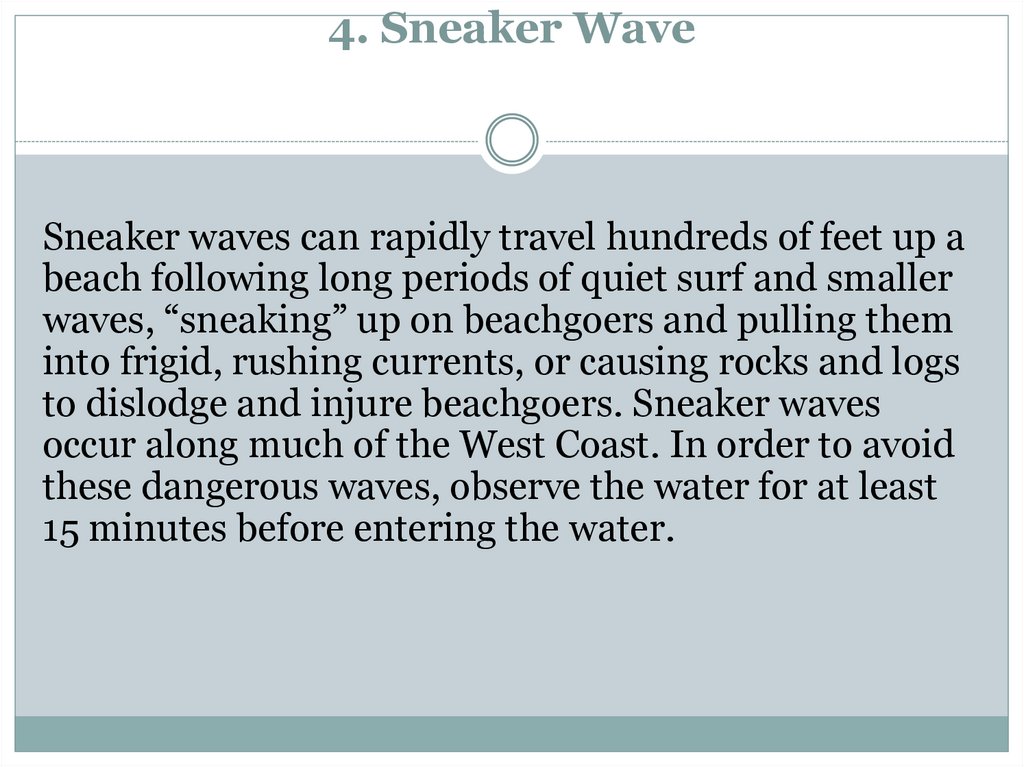

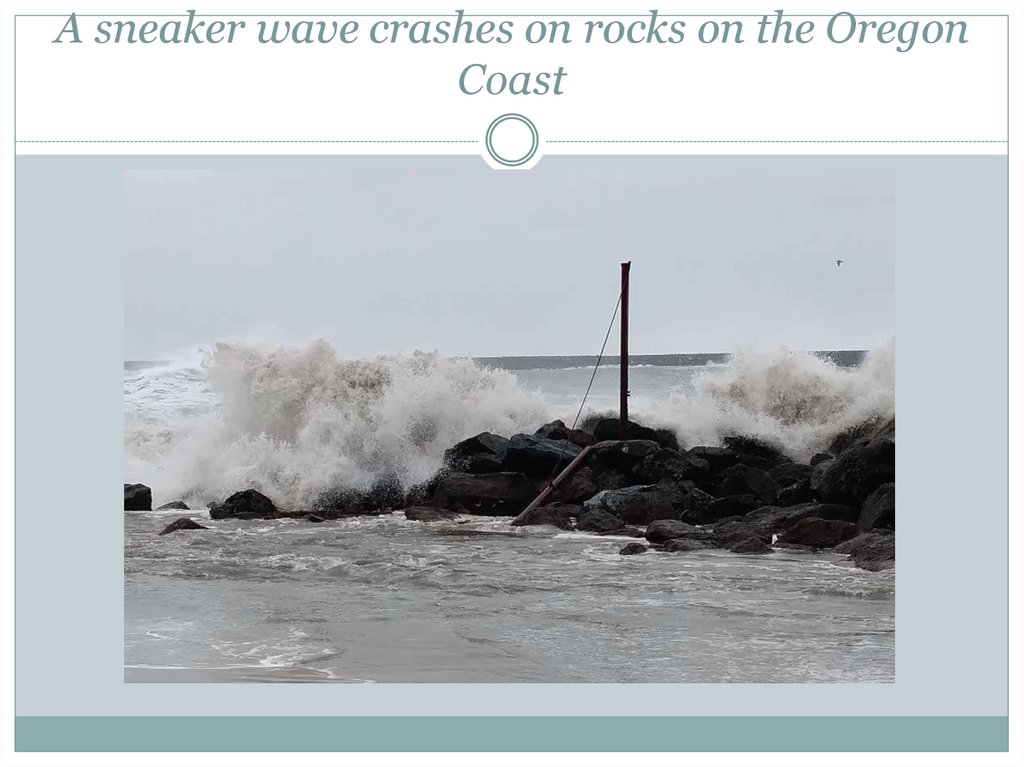

4. Sneaker WaveSneaker waves can rapidly travel hundreds of feet up a

beach following long periods of quiet surf and smaller

waves, “sneaking” up on beachgoers and pulling them

into frigid, rushing currents, or causing rocks and logs

to dislodge and injure beachgoers. Sneaker waves

occur along much of the West Coast. In order to avoid

these dangerous waves, observe the water for at least

15 minutes before entering the water.

38.

A sneaker wave crashes on rocks on the OregonCoast

39.

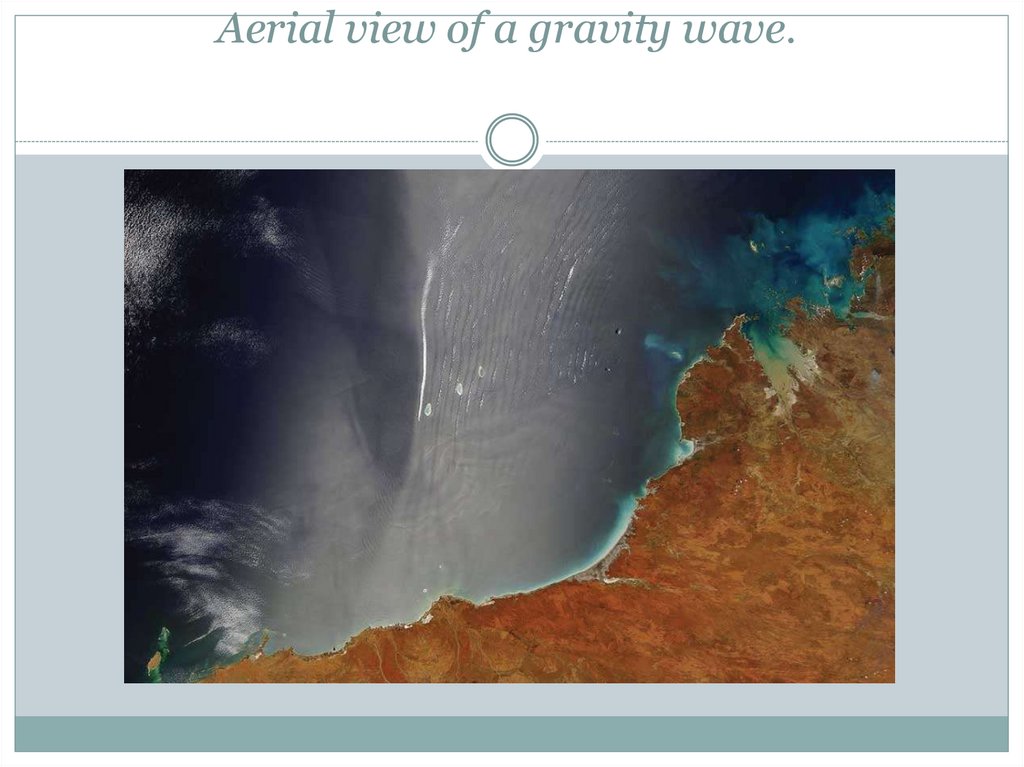

5. Gravity WaveGravity waves, not to be confused with gravitational

waves, form when air is pushed up and gravity pulls

the air back down. On its way down, air displaces

ocean water, forming waves that look like vertical

channels. There are different types of gravity waves.

Gravity waves that form on the surface of the water

are called surface gravity waves. Waves that occur

inside of a body of water are called internal waves.

Waves created by wind on the surface of the water

are wind-generated waves.

40.

Aerial view of a gravity wave.41.

How Healthy Are Earth's Oceans?In a new perspective on ocean health, one that looks

through the lens of both humans and the natural world,

scientists give Earth's seas a grade of 60 out of 100,

meaning there's lots of room for improvement, they say.

The new index ranks oceans' health and the benefits they

provide to humans using 10 categories, such

as biodiversity, clean waters, ability to provide food for

humans and support of the livelihood of people living in

coastal regions

In addition to assessing the present, the index provides a

benchmark against which to measure progress in the

future, writes the research team led by Benjamin Halpern

at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and

Synthesis in California.

42.

The scores on individual goals varied by country"The global score of 60 is a strong message that we are not

managing our use of the oceans in an optimal way," study

researcher Bud Ris, president and CEO of the New England

Aquarium said in a statement. "There is a lot of opportunity for

improvement, and we hope the Index will make that point

abundantly clear."

Countries' individual scores ranged from 36 to 86, with the Atlantic

coast of the west African nation Sierra Leone ranking the least

healthy, while the protected Pacific waters around Jarvis Island, an

uninhabited island designated a U.S. wildlife refuge ranked as the

healthiest.

In general, developed countries performed better than developing

nations, however, there were exceptions. Poland and Singapore

scored poorly, 42 and 48, respectively, while some developing

tropical nations, such as Suriname and Seychelles scored relatively

well, at 69 and 73, respectively.

43.

Here are the 10 goals upon which the ranking isbased

1) Food provision: This goal refers to the amount of seafood a

country catches or grows, all sustainably, from its waters.

2) Artisanal fishing: The opportunity for the small-scale fishing

efforts that are particularly crucial in developing nations.

3) Natural products: The sustainable harvest of living, non-food

natural products, such as corals, shells, seaweeds and fish for the

aquarium trade. It does not include bioprospecting, oil and gas or

mining products.

4) Carbon storage: The protection of three habitats, mangroves,

seagrasses and salt marshes, which store carbon, keeping it out of

the atmosphere and therefore mitigating global warming.

5) Coastal protection: The presence of natural habitats and barriers,

including mangroves, coral reefs, seagrasses, salt marshes and sea

ice, which physically protect coastal structures, like homes, and

uninhabited places, like parks.

44.

6) Coastal livelihoods and economies: Jobs and revenue producedfrom marine-related industry, alongside the indirect benefits of a

stable coastal economy.

7) Tourism and Recreation: The value people place on experiencing

and enjoying coastal areas, not the economic benefit which is

included in coastal economies.

8) Clean waters: Whether or not waters are free from oil spills,

chemicals, algal blooms, disease-causing pathogens, including those

introduced by sewage, floating trash, mass kills of organisms and

oxygen-depleted conditions.

9) Biodiversity: The extinction risk faced by species as well as the

health of their habitats.

10) Sense of Place: Aspects that people value as part of their

identity, including iconic species and places with special cultural

value.

45.

WHAT NEEDS TO HAPPEN?The pragmatic response is to cut carbon emissions as far and as fast as

possible, and at the same time, to fully protect very large marine areas to

help Ocean systems build resilience to the changes happening around

them.

There is more and more evidence that ‘blue carbon’ plays a critical role in

maintaining the health of our biosphere. This is the ability of mangroves,

sea grass beds, fish and marine mammals to play a huge role in

sequestering and storing carbon. By protecting and restoring these crucial

habitats and species, the more carbon will be sequestered and stored

resulting in a healthier planet, which is better for us all.

We also need to make sure that any extractive activities, like fishing or

mining, are sustainable, precautionary, and take account of their impacts

on the entire ecosystem, particularly in a time of change.

Studies have shown that coral reefs for example have a much greater

chance to recover from the effects of bleaching if other stresses have been

minimised or eliminated. For example, areas in no-take marine reserves

where fishing is prohibited have been shown to be more resilient

46.

OCEAN HEATINGIn addition to changing chemistry, the Ocean is also warming. A paper in

the journal Science Advances (March 2017), outlines that the rate of Ocean

warming has quadrupled since the late 20th century, with increasingly more

heat finding its way down into the deep Ocean.

About 93% of all the excess energy trapped in the Earth system by manmade greenhouse gases goes towards heating the Ocean – compared to 1%

for the atmosphere.

If the same amount of heat that’ went into the top 2 kms of the Ocean

between 1955–2010, had gone into the lower 10 kms of the atmosphere,

then the Earth would have seen a warming of 36°C. We therefore owe it to

the Ocean that life goes on.

Ocean warming leads to a whole range of impacts on Ocean life, most

importantly the forced migration of marine species. The knock-on effects of

these changes cannot be underestimated: they threaten food security; the

very existence of coastal communities and the informal economies that

keep these communities intact. Furthermore, they will play a role in human

migrations as these changes impact on some of the most vulnerable peoples

around the world.

47.

DEOXYGENATIONWarming also leads to hypoxia – lack of oxygen – in parts of the

Ocean as it impacts on the microscopic plants that live in the Ocean

and are responsible for more than half the oxygen we breathe.

Oxygen loss from warming has alarming consequences for global

oceanic oxygen reserves, which have already been reduced by 2%

over a period of just 50-years (from 1960 to 2010).

Ocean regions with low oxygen concentrations are expanding, with

around 700 sites worldwide now affected by low oxygen conditions

– up from only 45 in the 1960s.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

warns that at a global-scale, warming-induced oxygen loss is driving

progressive persistent changes in nutrient cycling and recycling,

species distributions, marine ecosystem services and habitat

availability.

48.

Solving Humanity’s Grand Challenges Requires a Healthy OceanHuman well-being and human rights are inextricably tied to the

health of the ocean, yet ocean conservation work is often isolated.

Last month, as the United National General Assembly focused on

tackling the grand challenges represented by the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), both the ocean goal (aka Goal 14, “Life

Under Water”) and me, as a marine biologist, were a bit lonely.

At one event, guests were asked to put a sticker on their name tag

indicating the goal they most supported. Of course, I chose the

ocean goal: “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and

marine resources for sustainable development.” And until a

colleague arrived, I was the only one representing the ocean. What

was supposed to be a conversation starter turned me into a

wallflower. It was a poignant reminder of how misunderstood and

marginalized ocean conservation issues often are — and to our

global detriment.

49.

Healthy oceans equal healthy fish for the world’s poorestOur oceans contribute to food security. Fish, shellfish and seafood

are key food categories for big parts of the population. However, if

not sustainably managed, fishing can damage fish habitats.

Ultimately, overfishing impairs the functioning of ecosystems and

reduces biodiversity, with negative consequences for sustainable

social and economic development. Based on an analysis of fishing

stocks, world marine fish stocks operating within biologically

sustainable levels declined from 90 percent in the mid-1970s to 69

percent in 2013.

What is particularly significant is that a decline in fish

populations poses greater risks for poor people in developing

countries. According to the United Nations, 820 million people do

not have enough to eat . 460 million of these people live in major

fish-dependent nations, countries like the Philippines, Indonesia,

and Mozambique. Seafood is their crucial source of healthy protein

and important micronutrients like iron, omega-3 fatty acids, zinc and

vitamins A and B12

50.

Healthy oceans equal healthy terrestrial ecosystemsOur seas and oceans have provided us with all these benefits while

at the same time absorbing large chunks of the environmental

implications our polluting activities have created. Since the

beginning of the industrial revolution, the ocean has absorbed about

one third of the carbon dioxide released by human activities,

thereby mitigating the full impact of climate change.

However, this comes at a steep ecological price. Greenhouse gas

emissions are increasing the acidity of the ocean and if we continue

business as usual, the ocean could become 150 percent more acidic

by 2100 [4]. This would be catastrophic for all ocean life as it would

lead to a reduction of plankton, threatening the survival of these

organisms and unique ecosystems.

Beyond climate change, our oceans protect coastal areas from

flooding and erosion. In fact, coastal and marine resources

contribute an estimated $28 trillion to the global economy each year

through ecosystem services. But there again, pollution of both land

and seas is a threat in many coastal regions.

51.

5 Ways to boost ocean healthPreserving the ocean wealth

Keeping our oceans clean

Improving coastal environments

Increasing ocean productivity sustainably

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

ecology

ecology