Similar presentations:

Getting Started: Planning and Writing Business Messages

1. Getting Started: Planning and Writing Business Messages

CFR CHAPTER 2; CWH 6-16.2. Learning objectives

Upon completing the readings from Week 3, you will be able toIdentify the components that make up the writing process specific to

the context of business.

Adopt individual techniques to plan a message, generate content, avoid

writer’s block, and revise/edit/proofread.

3. Writing is a process

As Boromir implies in this version of the notedinternet meme from Lord of the Rings, producing a

completed message is never achieved in a single step.

Whether composing an essay for university or a memo for

an organization, writing involves a number of steps from

planning to completing the final document. Even a “quick

email” requires some planning and proofreading. This

week, we look closely at the individual steps in the process

of writing.

(“One Does Not Simply”)

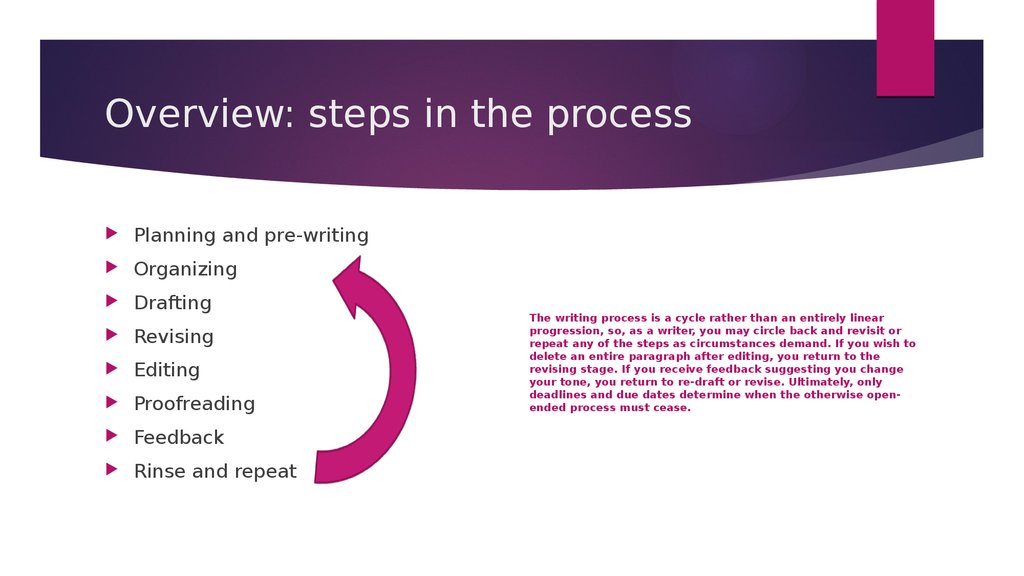

4. Overview: steps in the process

Planning and pre-writingOrganizing

Drafting

Revising

Editing

Proofreading

Feedback

Rinse and repeat

The writing process is a cycle rather than an entirely linear

progression, so, as a writer, you may circle back and revisit or

repeat any of the steps as circumstances demand. If you wish to

delete an entire paragraph after editing, you return to the

revising stage. If you receive feedback suggesting you change

your tone, you return to re-draft or revise. Ultimately, only

deadlines and due dates determine when the otherwise openended process must cease.

5. Planning and pre-writing

The first step for any writing project (and any communications endeavour)is considering the rhetorical situation, the circumstances surrounding

the composition of the message. This includes, first and foremost,

establishing the nature of the audience (Who are they? What are they

like?), your intended purpose, the best channel for the message, and

any “limitations on what can be said” (Meyer 48). Planning effectively

reduces the chance of error and the need to redraft or clarify messages,

which costs time and money while diminishing the reputation of the

sender.

6. Purpose

Within the rhetorical situation, the first consideration when writing isdetermining your purpose, why you are writing. Are you primarily looking

to inform your audience as in an expense report, or is your first goal to

persuade as in a proposal? All other purposes can fit under the umbrella

of these two, and the two may overlap. An advertisement informs about a

product or service while persuading the potential customer to use it. An

internal announcement to staff about how to submit a timesheet seeks to

inform. Perhaps it goes without saying that you need to know why you are

writing before getting started, but thinking consciously about purpose

helps ensure your message is focused.

7. Know the audience: The most important consideration

In case you hadn’t noticed in the previousreadings, the necessity of knowing your audience

has already been emphasized as part of both

cross-cultural and ethical communication.

Purpose and audience are usually the two

foundational aspects to think about when

preparing to write. It’s fairly easy to know your

purpose—you know if you have to give bad news

or if you need to persuade. Knowing the audience

can be more challenging, and given how crucial it

is for all the professional writing you do, we’re

going to take some time to talk about how to do

this in depth here.

(Ganzer)

8. Why does it matter so much?

As is the case when considering culturaldifferences and ethics, empathizing with your

audience, putting yourself in their shoes and

understanding what they want, is the best way to

know what and how to write for them. If you know

your manager is very precise and likes detail,

you’d add more information to the memos you

send her and use a certain tone. If you know the

potential buyers for your product are bored by

complex information but like to feel happy, you

could decide to use the image of a puppy in an

advertisement to sell a beer. By understanding

“the needs and mindset” of your audience, you

can then tailor your message to appeal to them

(Meerman Scott 109).

9. How to do it?

David Meerman Scott, in his now classic book The NewRules of Marketing and PR, talks about creating

buyer personas or buyer profiles, “fictional, generalized

representations of your ideal customers” (Vaughan). For

an audience analysis (your first writing assignment), you

do something similar, trying to get a thorough sense of

who your potential reader will be, then craft your written

work accordingly.

Audience analysis can encompass a range of items such

as whether your audience is likely to be resistant or

compliant, what they know (and need to know) in terms of

background, what their education level and other

demographic traits are, and what their personalities

are like. This is easier for a simple audience comprised

of one individual, especially one you already know, but

more difficult when writing to multiple people (a complex

audience) or those with whom you’ve never spoken.

(Vaughan)

10. Online Audiences

Analyzing your audience may seem particularly daunting whenwriting online content, a situation where you have a potential

audience of more than a billion people with internet access

across the whole world.

You can’t realistically or effectively target the entire Web with

what you write but instead need to tailor digital content to

particular niche audience. For example, instead of blogging

about cars, you might write a blog for Canadian owners of the

second-generation Mazda 3 automobile. Odds are that more

general content will not be found or will be buried online while

the specific focus, the niche topic, will be found more easily by a

certain audience.

11. Examples

David Meerman Scott gives a concreteexample of how a targeted audience

analysis was used to generate campaign

materials for the 2004 Presidential election

in the United States. Instead of trying to

appeal to a general audience of voters,

individualized material was directed toward

specific niche groups like “’NASCAR Dads’

(rural working-class males, many of whom

are NASCAR fans) and ‘Security Moms’

(mothers who were worried about terrorism

and concerned about security)” (Meerman

Scott 122).

12. And specifically, online…

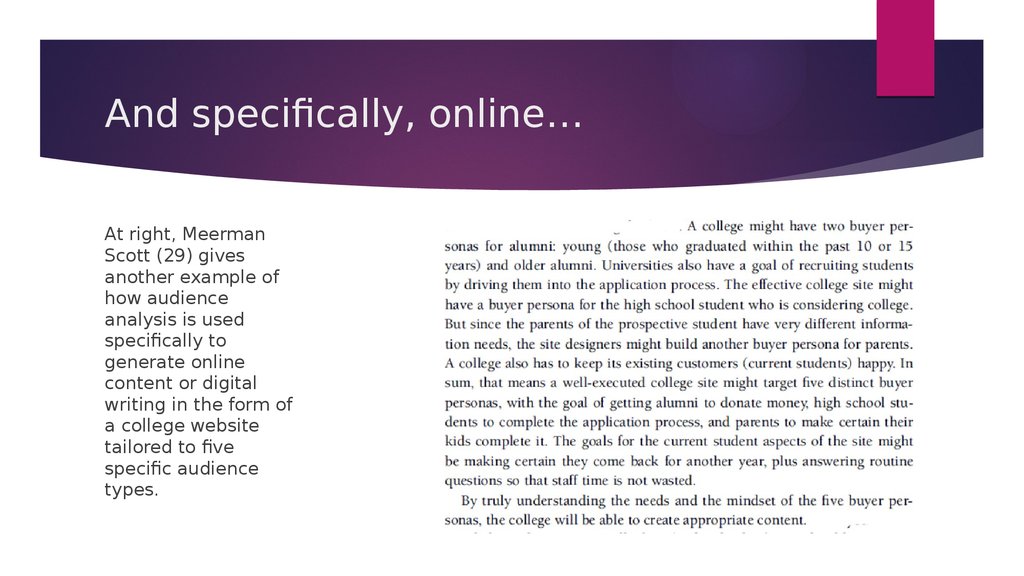

At right, MeermanScott (29) gives

another example of

how audience

analysis is used

specifically to

generate online

content or digital

writing in the form of

a college website

tailored to five

specific audience

types.

13. Keywords

A unique aspect of considering the audience when writing onlinedocuments for an organization, whether it is promotional material, a

website, a blog or anything else available to the public, is knowing how

your desired niche audience thinks in terms of keywords – when they

search the Web, what will they be looking for when searching for

something related to your organization? Part of empathizing with your

audience therefore requires brainstorming search terms they might use

and working them into what you are writing. For example, if you are a

book publisher and are promoting a new novel about a vampire and

human in love, you might use “paranormal romance” or mention Twilight

in order to come up in search results of those who are searching these

terms.

14. Tools: Approaches to audience analysis

To begin, identify the audience or rather audiences.Who is the primary audience, the main recipient

of the message? While the first reader(s)to get your

message, termed the initial audience, might be

the same, this could also be the person who

initiated the communication. This individual could

also be the gatekeeper audience, with the power

to stop your message. Are there additional parties

such as lawyers or the media who may read and act

on the communication after the primary audience?

These would comprise the secondary audience.

Finally, your message could have a watchdog

audience if there are any parties that don’t have a

direct part in your message but who can exert an

influence on it such as a political or regulatory

agency.

(Blackwell)

15. Research

Once you’ve identified who your audience is, learn about themDemographics, the statistical data

on your reader(s), can be helpful in

identifying their attributes. Think of

common census data such as age,

education level, location, gender and

ethnicity. Targeting communications

to retirees would involve different

approaches than addressing young

parents as would writing a farmer in

Winnipeg as opposed to a banker in

Toronto.

Psychographics, the interests, attitudes and opinions (IAO

variables) of your audience are also a valuable tool, highly

used in marketing. Some examples are the goth subculture,

NFL football fans, or those interested in “green” living.

(Rupert)

(Pogrzeba)

16. Myers-Briggs Personality Type

In the 1940s and ‘50s, Elizabeth BriggsMyers identified and described a set of

sixteen personality types based on

individual behavioral preferences such as

introversion vs. extroversion, feeling vs.

thinking. These indicators have since been

used as a means of understanding the

needs of employees, patients, clients,

audiences, and oneself. You can take an

unofficial online quiz to gain some sense of

your personality type. You can also view

the Myers-Briggs types of

notable individuals.

(Jordy)

17. Why?

Using some or all of these tools to analyze your audience helps you craft thecommunication to appeal to them.

If your reader is known to be hostile to an idea, you would take more time

to develop its persuasive aspect.

If you’re writing a technical report for engineers with graduate degrees

you’d choose a different level of diction and use different vocabulary than

if you were creating a public service ad aimed at teens.

If you know your manager is an introvert, you might send an email to

request something rather than asking for a personal meeting, as

introverts prefer to mull over content and are more comfortable reading

material carefully than making an immediate face-to-face decision.

18. Which channel to use

As suggested in the previous slide, knowing your audience’s personalitycan also influence which channel you select in order to convey the

message. Page 54 of our textbook, CFR, provides a detailed list of other

factors governing the choice of channel independent of audience

considerations, such as how quickly the information needs to be received,

how much information needs to be provided, and whether there needs to

be a “paper trail” recording the content.

19. Generating content

Once you have completed the planning of your message, youcan apply a variety of techniques to develop written content and

overcome writer’s block. Brainstorming involves simply thinking

in a concentrated manner about your topic for a set period of

time, translating your ideas to a blank page (hardcopy or on

screen) by listing or freewriting. These are sometimes

considered part of brainstorming (see page 7 of the CWH)

though they really involve externalizing the ideas you have

generated.

(Marcos C.)

20. Freewriting

Freewriting involves writing non-stop,with no heed of grammar or

correctness, for a set period of time

(often ten minutes). You may then

engage in “focused freewriting,”

selecting a particular aspect of what

you have freewritten and freewriting

again on that idea alone. Ultimately,

emphasizing the recursive nature of the

writing process, your job is to go back

and revisit the material, making use of

the best parts and putting order to your

output.

(Oliveri)

21. Questioning

Another approach is to make use of the six“journalist’s questions”—Who? What?

Where? When? Why? How?—asking these

about your topic. Doing this provides a

guide for issues, topics, and considerations

that may be worth addressing in the

message. For example, in announcing a

policy change, you might ask “What

specific changes need to be mentioned?

Who is affected? Why are we changing the

policy? How will this affect employee

behavior?” Answering these questions

furnishes the content for your message.

(Thwip!)

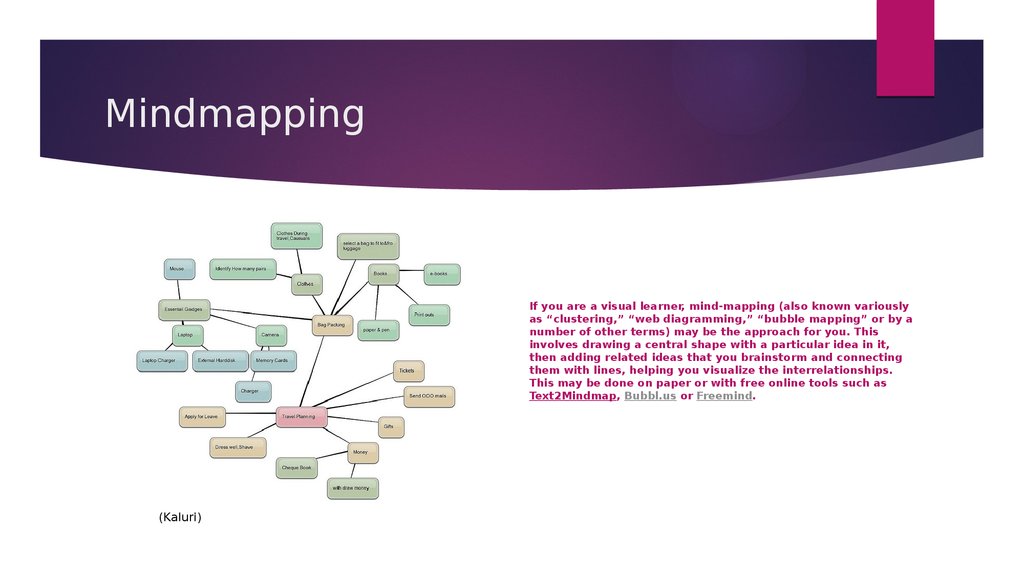

22. Mindmapping

If you are a visual learner, mind-mapping (also known variouslyas “clustering,” “web diagramming,” “bubble mapping” or by a

number of other terms) may be the approach for you. This

involves drawing a central shape with a particular idea in it,

then adding related ideas that you brainstorm and connecting

them with lines, helping you visualize the interrelationships.

This may be done on paper or with free online tools such as

Text2Mindmap, Bubbl.us or Freemind.

(Kaluri)

23. Organizing

To some degree organization occursnaturally while moving from freewriting

to focused freewriting, from answering

the journalist’s questions, or from

drawing a mindmap, but, as a final part

of planning. many writers prefer to map

out the structure of a document using a

outline, which can be as formal as

having a hierarchical list using Roman

numerals, Arabic numerals, and letters,

or more casual, by grouping and

classifying similar ideas on paper.

I. Policy change

1. No alcohol in breakroom.

a)

Beer

b)

Liquor

2. No gambling in breakroom.

c)

Poker

d)

Blackjack

24. Outlines create structure

Formally written messages areconstructed with individual sections

such as an introduction, topic

sentences, body paragraphs, and a

conclusion. Just as one wouldn’t

construct a house without a blueprint,

so too some sort of organizational plan

—a blueprint for your house built of

words—is essential when writing.

(Collapsed House)

25. Drafting and Revision

When planning ends, writing (drafting)and rewriting (revision) take place,

though some form of drafting and

revision may already have taken place

while freewriting and performing

focused freewriting as a means of

developing ideas.

During drafting and revising it is not

uncommon for writer’s block to occur.

Our text (Meyer 59-60) provides some

useful advice on getting around this.

(Coleman)

26. Beating writer’s block

A major cause of writer’s block while drafting (or re-drafting) is the desire for perfection,especially a concern for lower-order issues like correct grammar or choosing exactly the

right word. This idea should be abandoned—one can edit the text later as endless tweaks

or a concern for correctness can hinder the completion of drafting. This is an occasion

where the stages in the writing process should be separated. Revision is distinct from

editing in that it focuses on the large-scale or macro issues such as content and

organization. You may want to move, delete, or add a paragraph. You may reconsider your

entire approach at persuasion in the message. This is part of revision.

Editing should occur later as a distinct step once the higher-order matters are completed to

your satisfaction. However, the ease of editing using word processing software makes it

tempting to do so while still in the middle of drafting or revising. This can be a wasted

effort if you later delete a large chunk of text you’ve spent time editing in addition to being

a major cause of writer’s block. So, leave the lower-order, micro concerns for later.

27. Beating writer’s block

Another tip is to escape writer’s block is toleave the work for a time, either getting

away your desk for a while, even a day or

more, to revisit your content with a

recharged mind.

Alternatively, skip to another section in

the work. If you are having difficulty

drafting the introduction, do the body first.

There’s no rule that you need to progress

through the document in linear order.

If all else fails, try freewriting again as a

way to generate content in the middle of

the drafting process.

(Albaih)

28. Revising, editing, proofreading

Revising usually refers to large-scale changes to a draft such asthose involving content or structure. It implies “seeing again,”

which requires you to visit your work with fresh eyes. Thus, it is

best to leave the work for some time, ideally a day or more,

before reviewing it. Sending the draft to other readers for

feedback can be valuable during the revision stage as well. You

will have the opportunity to engage in this sort of peer review

process for some of the assignments during the term.

(Humpohl)

29. Editing, proofreading

A similar principle applies to editing andproofreading at the end of the writing process.

Besides setting the work aside before looking for

individual issues of wording or grammar, printing

a hardcopy can help. We tend to skim when we

read on screen and therefore miss errors.

Reading the text aloud is also a fantastic way

to hear issues of wording (awkward phrasing,

wordiness) or sentence structure (run-ons,

fragments). Better yet, have someone read the

document to you or use a text-to-speech feature,

so you can concentrate on hearing the content.

Lastly, run a spell check on your document but

realize it will not catch everything (as the widely

circulated poem at right reveals), so scan it closely

yourself.

Eye halve a spelling chequer

It came with my pea sea

It plainly marques four my revue

Miss steaks eye kin knot sea.

Eye strike a key and type a word

And weight four it two say

Weather eye am wrong oar write

It shows me strait a weigh.

As soon as a mist ache is maid

It nose bee fore two long

And eye can put the error rite

Its rare lea ever wrong.

Eye have run this poem threw it

I am shore your pleased two no

Its letter perfect awl the weigh

My chequer tolled me sew.

30. It takes time

If there is one overarching idea that wecan take away from the readings this

week, it is that the writing process can—

and should—take time. Not only do we go

through the steps but we may go through

them multiple times for a single document.

Paralleling the Slow Food and Slow Travel

movements, Slow Writing is the best way

to optimize the writing experience. Of

course, in real life, deadline pressures can

hasten the process, so it is important to

budget and manage your time effectively.

(Depolo)

31. Study Questions

Do you make use of any of the methods of content generation andrevision detailed in the readings of the week? If not, would you? Does

one of them seem particularly appealing to you? Why?

Consider question 4 on page 69 of CFR. Identify for yourself the

purpose for each of the forms of writing listed there.

32. Works Cited

Albaih, Khalid. “Waiting.” Illustration. Flickr. 12 Sep. 2012. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.Blackwell, David. “Silvester the Guard Dog.” Photograph. Flickr. 14 Apr. 2012. Web. 5 Jul.

2014.

Collapsed house. Harris & Ewing. Photograph. Library of Congress. 1923. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

Coleman, Marie. “2.19.10.” Photograph. Flickr. 19 Feb. 2010. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

Depolo, Steven. “SLOW.” Photograph. Flickr. 24 Apr. 2010. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

Ganzer, Rupert. “KOL Audience.” Photograph. Flickr. 9 Dec. 2010. Web. 5 Jul. 2014.

Humpohl, David. “eye see you.” Photograph. Flickr. 30 Oct. 2005. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

Jordy. “I Will Not Be Graphed.” Photograph. Flickr. 22 Sep. 2008. Web. 5 Jul. 2014.

Meerman Scott, David. The New Rules of Marketing and PR. New York: Wiley, 2013. Print.

Meyer, Carolyn. Communicating for Results: A Canadian Student’s Guide. Don Mills:

Oxford UP, 2014.

33. Works Cited (continued)

Kanuri, Kalyan. “Travel Planning – Mindmap.” Image. Flickr. 26 Jul. 2008. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.Marcos C. “Brainstorm.” Photograph. Flickr. 17 Feb. 2011. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

Oliveri, Mike. “Brainstorm.” Photograph. Flickr. 30 Jun. 2007. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

“One does not simply.” Image. Imgflip. n.d. Web. 5 Jul. 2014.

Pogrzeba, Norbert. “Létain.” Photograph. Wikipedia Germany.16 Dec. 2006. Web. 5 Jul.

2014.

Rupert, Nathan. “Ready for War.” Photograph. Flickr. 27 Sep. 2009. Web 5 Jul. 2014.

Thwip! “more at eleven.” Photograph. Flickr. 15 Dec. 2004. Web. 6 Jul. 2014.

Vaughan, Pamela. “How to Create Detailed Buyer Personas for Your Business.” 28 May

2015. Web. 3 Sep 2016.

business

business