Similar presentations:

Beliefs, Values, and Cultural Universals

1.

Beliefs, Values, andCultural Universals

Ruzmetova Diana Komilovna act.assist.prof. (PhD)

2.

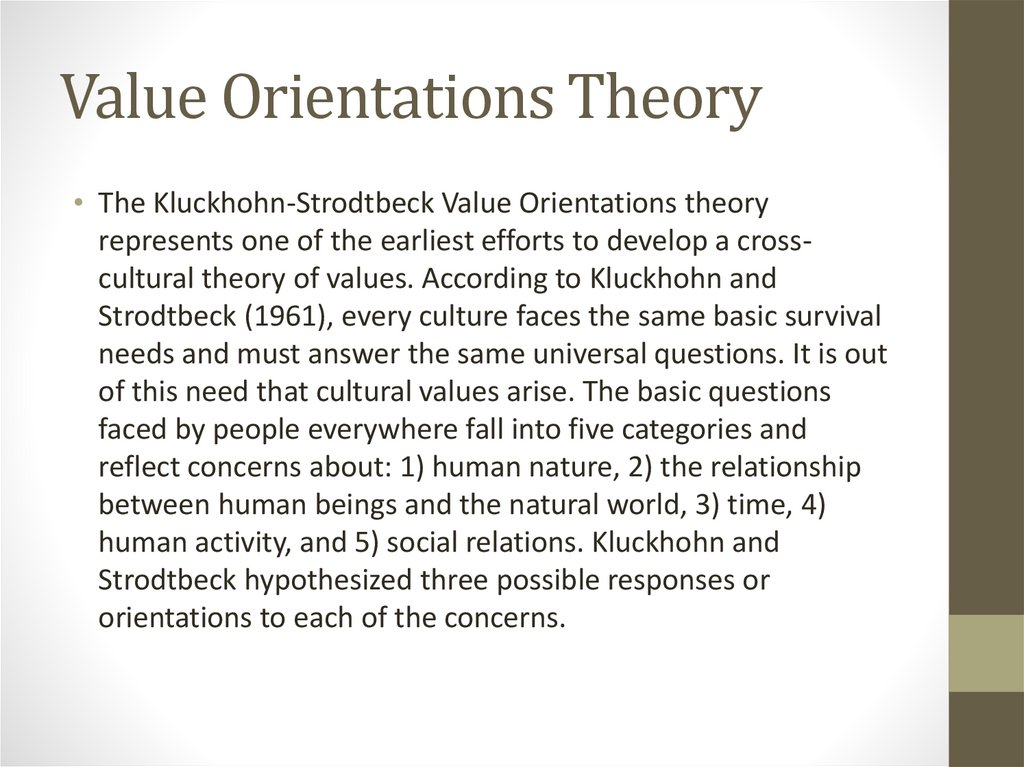

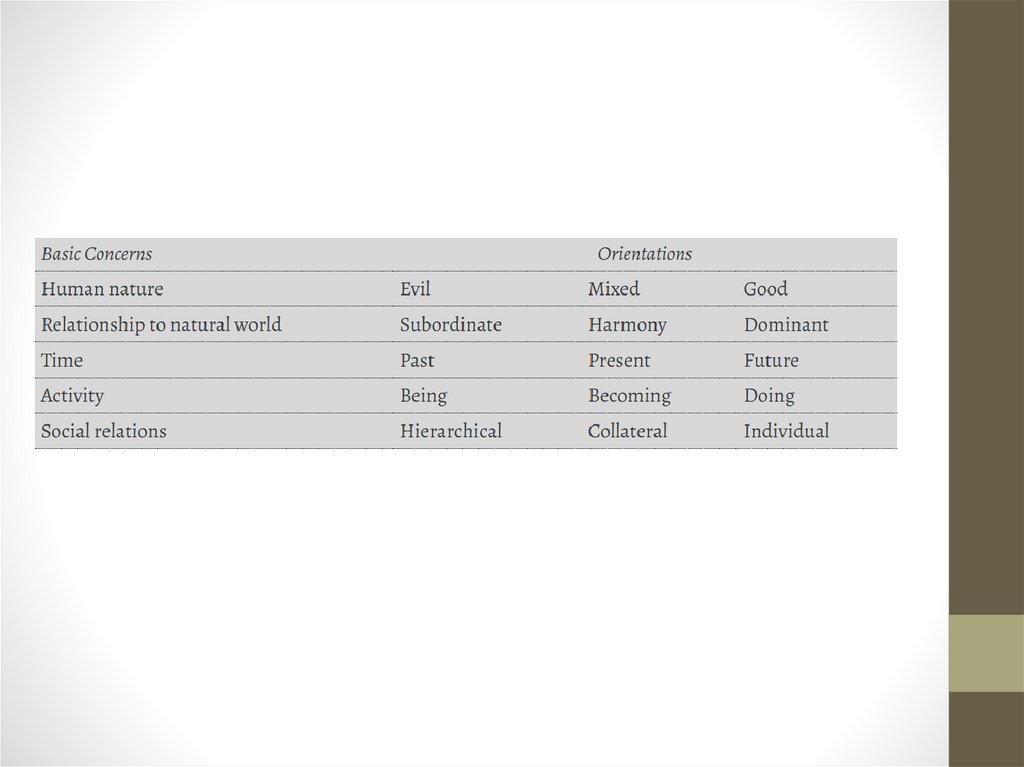

Value Orientations Theory• The Kluckhohn-Strodtbeck Value Orientations theory

represents one of the earliest efforts to develop a crosscultural theory of values. According to Kluckhohn and

Strodtbeck (1961), every culture faces the same basic survival

needs and must answer the same universal questions. It is out

of this need that cultural values arise. The basic questions

faced by people everywhere fall into five categories and

reflect concerns about: 1) human nature, 2) the relationship

between human beings and the natural world, 3) time, 4)

human activity, and 5) social relations. Kluckhohn and

Strodtbeck hypothesized three possible responses or

orientations to each of the concerns.

3.

4.

What is the inherent nature ofhuman beings?

• This is a question, say Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, that all

societies ask, and there are generally three different

responses. The people in some societies are inclined to

believe that people are inherently evil and that the society

must exercise strong measures to keep the evil impulses of

people in check. On the other hand, other societies are more

likely to see human beings as born basically good and

possessing an inherent tendency towards goodness. Between

these two poles are societies that see human beings as

possessing the potential to be either good or evil depending

upon the influences that surround them. Societies also differ

on whether human nature is immutable (unchangeable) or

mutable (changeable).

5.

What is the relationshipbetween human beings and the

natural world?

• Some societies believe nature is a powerful force in the face of

which human beings are essentially helpless. We could

describe this as “nature over humans.” Other societies are

more likely to believe that through intelligence and the

application of knowledge, humans can control nature. In other

words, they embrace a “humans over nature” position.

Between these two extremes are the societies who believe

humans are wise to strive to live in “harmony with nature.”

6.

What is the best way to thinkabout time?

• Some societies are rooted in the past, believing that people

should learn from history and strive to preserve the traditions

of the past. Other societies place more value on the here and

now, believing people should live fully in the present. Then

there are societies that place the greatest value on the future,

believing people should always delay immediate satisfactions

while they plan and work hard to make a better future.

7.

What is the proper mode ofhuman activity?

• In some societies, “being” is the most valued orientation.

Striving for great things is not necessary or important. In other

societies, “becoming” is what is most valued. Life is regarded

as a process of continual unfolding. Our purpose on earth, the

people might say, is to become fully human. Finally, there are

societies that are primarily oriented to “doing.” In such

societies, people are likely to think of the inactive life as a

wasted life. People are more likely to express the view that we

are here to work hard and that human worth is measured by

the sum of accomplishments.

8.

What is the ideal relationshipbetween the individual and

society?

• Expressed another way, we can say the concern is about how a

society is best organized. People in some societies think it most

natural that a society be organized hierarchically. They hold to the

view that some people are born to lead and others to follow.

Leaders, they feel, should make all the important decisions. Other

societies are best described as valuing collateral relationships. In

such societies, everyone has an important role to play in society;

therefore, important decisions should be made by consensus. In still

other societies, the individual is the primary unit of society. In

societies that place great value on individualism, people are likely to

believe that each person should have control over his/her own

destiny. When groups convene to make decisions, they should follow

the principle of “one person, one vote.”

9.

• Space – Should space belong to individuals, to groups(especially the family) or to everybody?

• Work – What should be the basic motivation for work? To

make a contribution to society, to have a sense of personal

achievement, or to attain financial security?

• Gender – How should society distribute roles, power and

responsibility between the sexes? Should decision-making be

done primarily by men, by women, or by both?

• The Relationship between State and Individual – Should rights

and responsibilities be granted to the nation or the individual?

10.

Individualism vs. collectivismIndividualism vs. collectivism anchor opposite ends of a continuum

that describes how people define themselves and their

relationships with others. Countries that score higher on

individualism measure are considered by definition less

collectivistic than countries that score lower. In more highly

individualistic societies, the interests of individuals receive more

emphasis than those of the group (e.g., the family, the company,

etc.). Individualistic societies put more value on self-striving and

personal accomplishment, while more collectivistic societies put

more emphasis on the importance of relationships and loyalty.

People are defined more by what they do in individualistic societies

while in collectivistic societies, they are defined more by their

membership in particular groups. Communication is more direct in

individualistic societies but more indirect in collectivistic societies.

The U.S. ranks very high in individualism, and South Korea ranks

quite low. Japan falls close to the middle.

11.

Masculinity vs. femininity• Masculinity vs. femininity refers to a dimension that describes

the extent to which strong distinctions exist between men’s

and women’s roles in society. Societies that score higher on

the masculinity scale tend to value assertiveness, competition,

and material success. Countries that score lower in

masculinity tend to embrace values more widely thought of as

feminine values, e.g., modesty, quality of life, interpersonal

relationships, and greater concern for the disadvantaged of

society. Societies high in masculinity are also more likely to

have strong opinions about what constitutes men’s work vs.

women’s work while societies low in masculinity permit much

greater overlapping in the social roles of men and women.

12.

Final reflection• Implicit in Hofstede’s work, in particular, is the idea that there

exists such a thing as a national culture. In discussing cultural

values, we have temporarily gone along with this suggestion.

However, in closing, let us raise the question of whether the

idea of national culture actually makes any sense. McSweeney

(2002: 110), echoing the sentiments of many other scholars

insists that, “the prefixing of the name of a country to

something to imply national uniformity is grossly over-used.”

In his view, Hofstede’s dimensions are little more than

statistical myths.

• In the chapters to come, we will suggest that culture is a term

better applied to small collectivities and explain why the idea

that there is any such thing as national culture may be a mere

illusion.

culturology

culturology