Similar presentations:

Levels of categorization

1. Levels of categorization

LEVELS OF CATEGORIZATIONProf. V.I. Zabotkina

2. Levels of categorization

LEVELS OF CATEGORIZATIONSuperordinate

Basic

Subordinate

3. Basic level categories of organisms and concrete objects

BASIC LEVEL CATEGORIES OFORGANISMS AND CONCRETE OBJECTS

'Scientific classifications may be fascinating in their

complexity and rigidity, but are they really suitable

for human categorization?

So-called folk taxonomies suggest that we approach

hierarchies from the centre, that we concentrate on

basic level categories such as dogs and cars and that

our hierarchies are anchored in these basic level

categories.

4. Basic level categories of organisms and concrete objects

BASIC LEVEL CATEGORIES OFORGANISMS AND CONCRETE OBJECTS

All cognitive categories are connected with each other

in a kind of hierarchical relationship.

Dogs are regarded as superordinate to terriers, and

terriers as superordinate to Scotch terriers and bull

terriers; looking in the other direction, dogs are seen

as subordinate to mammals, and mammals as

subordinate to animals.

5.

Theprinciple underlying this hierarchical structure is the

notion of class inclusion, i.e. the view that the superordinate

class includes all items on the subordinate level.

The class 'animal' includes not only mammals, but birds and

reptiles as well.

On the next level, the class 'mammal' comprises not only dogs,

but cats, cows, lions, elephants and mice.

Still further down, the class 'dog' includes terriers, bulldogs,

alsatians, poodles, and various other kinds of dogs.

Similar hierarchies exist for man-made objects like vehicles,

which embrace cars, vans, bicycles, sledges, etc., and their

respective subdivisions.

All in all, it seems that the whole range of concrete entities in

the world can be hierarchically ordered according to the

principle of class inclusion. Starting from this notion of

hierarchy, the detailed classifications (or taxonomies) which

have been developed in many scientific fields may simply appear

to be an extension of the basic human faculty of categorization.

6.

All in all, it seems that the whole range of concrete entities inthe world can be hierarchically ordered according to the

principle of class inclusion. Starting from this notion of

hierarchy, the detailed classifications (or taxonomies) which

have been developed in many scientific fields may simply appear

to be an extension of the basic human faculty of categorization.

7. Superordinate categories

SUPERORDINATE CATEGORIES'If basic level categories are exceptional in many ways, how

do other types of cognitive categories differ from them? Are

other categories just 10 be regarded as poor relations or do

they have specific functions for which they are uniquely

equipped and which determine their category structure?

And how does the status of these categories affect our

notion of hierarchy? These questions will be discussed for

superordinate categories first, where they seem to be most

pressing.

8. Superordinate categories

SUPERORDINATE CATEGORIESWhen choosing the cognitive categories for their investigation

of prototypes, early researchers did not consciously distinguish

between basic level categories and other kinds of categories.

Quite naturally, they selected the categories that promised the

best results for the demonstration of the individual effects of

the prototype structure they had in mind.

Gestalt characteristics of categories and the fuzziness of category

boundaries could best be illustrated with basic level categories

like CUP and BOWL. Goodness-of-example ratings and

attribute listings involving family resemblances worked well

with cognitive categories such as FRUIT, FURNITURE and

VEHICLE, which are commonly placed on a superordinate

level. Yet when basic level categories were contrasted with the

superordinate (and subordinate) categories in the last section,

it became clear that an ideal prototype structure can only be

found on the basic level and that, seen from this angle,

superordinate categories are deficient in many ways.

9. The structure of superordinate categories and the notion of parasitic categorization

THE STRUCTURE OF SUPERORDINATE CATEGORIESAND THE NOTION OF PARASITIC CATEGORIZATION

To start with the most obvious deficiency of superordinate

categories, there is no common overall shape and, consequently,

no common underlying gestalt that applies to all category

members. However, this does not mean that we cannot approach

the objects categorized as FRUIT or FURNITURE or VEHICLE

holistically. Consider what you would do if you were asked to

provide a picture of these categories. You would probably draw an

orange, a banana, etc., to illustrate FRUIT, or a chair, a table and

a bed for FURNITURE, or a car, a bus and a motorbike for

VEHICLE. In other words, you would 'borrow' the gestalt

properties of the superordinate category from the basic level

categories involved — a first case of what will be

called parasitic categorization.

10. The structure of superordinate categories and the notion of parasitic categorization

THE STRUCTURE OF SUPERORDINATE CATEGORIESAND THE NOTION OF PARASITIC CATEGORIZATION

This principle of parasitic categorization is also reflected in the

way in which attributes are used in categorizing experiments.

Informants tend to list few category-wide attributes for

superordinate categories. Indeed, in the case of FURNITURE,

Rosch's informants did not suggest a single common attribute.

The most likely reason is that the common attributes available for

FURNITURE are so general and unobtrusive that informants do

not find them worth mentioning — think of 'large movable objects'

or 'things that make a house or flat suitable for living in'. Apart

from category-wide attributes, informants offer the names of basic

level categories which are members of the superordinate category

and, in addition, attributes of these basic level categories. In the

case of FURNITURE this means that informants will name the

basic level categories CHAIR, TABLE, BED, etc. and add a

number of attributes from the attribute inventory of these

cognitive categories, e.g. 'has legs', 'has a back', 'used to sit on' for

CHAIR, etc.

11.

12. Subordinate categories

SUBORDINATE CATEGORIES'We use subordinate terms like poodle or terrier and not basic

level terms like dog when we want to be more specific. This

specificity determines the way in which we categorize on the

subordinate level, and it is also responsible for the fact that

subordinate categories are often expressed by compounds and

other composite terms. .

The most frequent type of lexical category apart from basic level

categories are subordinate categories. There are many kinds of

dogs, of flowers, of cars and boats, of beds and tables, and all of

them can be understood in terms of cognitive categories. In some

cases, the structure of these subordinate categories is very

similar to the structure of basic level categories. Categories like

POODLE, TERRIER or ROSE have identifiable gestalts, they are

constructed round prototypes, have good and bad members, can

muster substantial lists of attributes and are expressed by simple

words. However, when we follow Brown (1990) and turn to more

extreme examples of subordinate categories, the differences

become more marked.

13. Subordinates: characteristics of category structure

SUBORDINATES: CHARACTERISTICSOF CATEGORY STRUCTURE

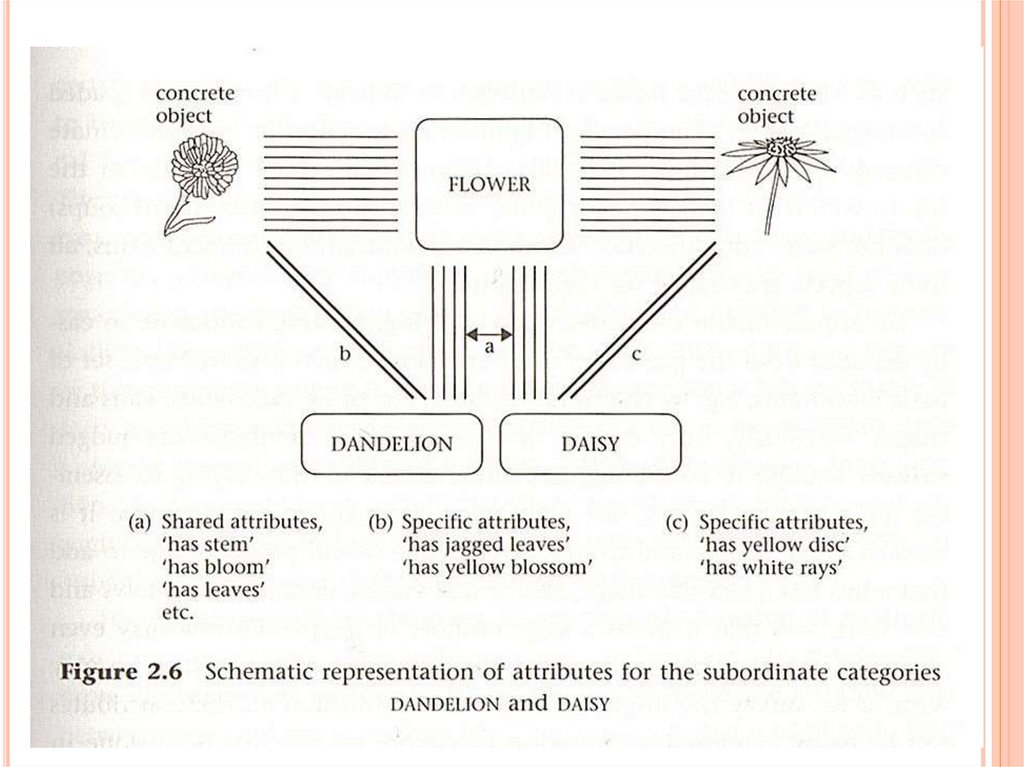

If we stick to flowers, but replace ROSE with DANDELION or DAISY,

we still have a fairly clear gestalt perception, including the holistic

impression of the overall shape, the jagged leaves, the yellow blossom of

dandelions or the distinction between the yellow disc and the white rays

typical of daisies. The difference between these categories and a category

such as ROSE becomes obvious when we start looking for prototypes of

dandelions or daisies.

How does an ordinary language user, someone who is neither a botanist

nor a lexicologist, single out a perfect dandelion or daisy? How does he or

she describe the difference between this perfect specimen and a poor one?

Indeed, the average language user will hardly attempt to distinguish

prototypical dandelions and daisies from lesser category members, both

in terms of individual examples and varieties. Moving from natural kinds

to man-made objects, such as coins, we find that subordinate categories

like DIME or QUARTER also do not yield prototypes that can be easily

distinguished from more marginal examples. All dimes and quarters are

very much alike, and can be regarded as equally good examples of the

category.

The reason is not that real-life examples of dandelions, daisies, dimes or

quarters are in fact identical. The differences in shape or colour (in the

case of dandelions and daisies) or in newness and gloss (for dimes and

quarters) which might emerge in a thorough scrutiny are simply

irrelevant for everyday categorization and do not influence our holistic

perception.

14.

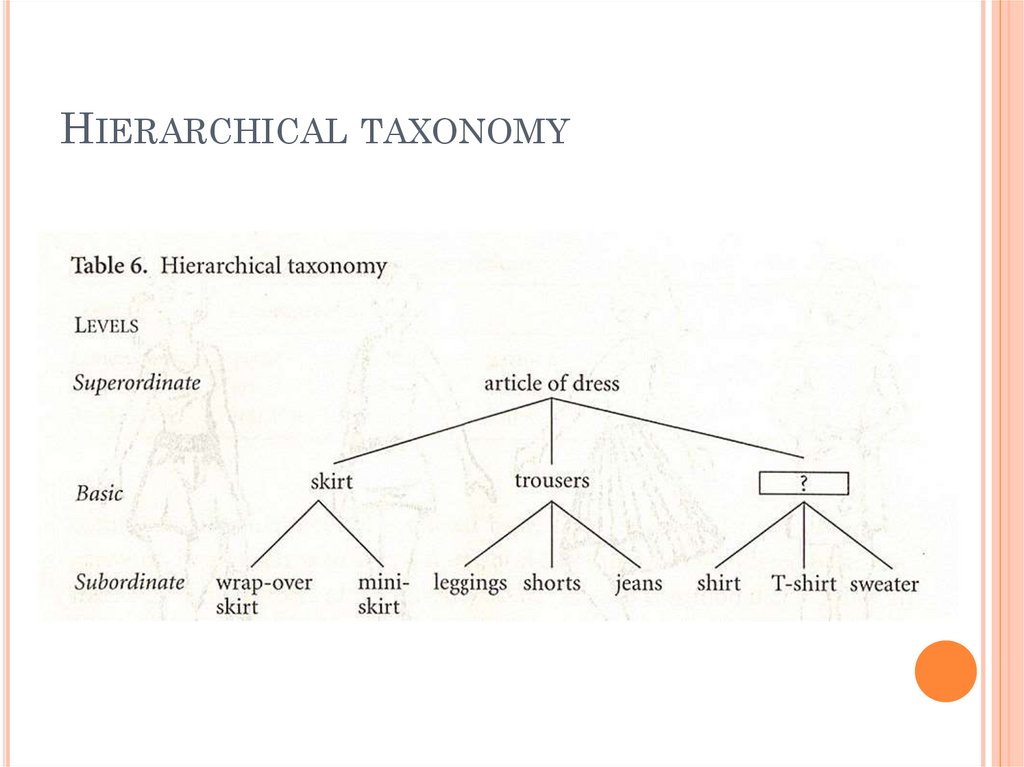

15. Hierarchical taxonomy

HIERARCHICAL TAXONOMY16. Fuzziness in conceptual domains: Problematical taxonomies

FUZZINESS IN CONCEPTUAL DOMAINS:PROBLEMATICAL TAXONOMIES

We saw that whenever categorization of natural

categories is involved, there is by definition some

fuzziness at the category edges. Tomatoes, for example,

can be categorized as either vegetables or fruit,

depending on who is doing the categorizing. The same

goes for the onomasiological domain.

For example, when we look at the basic level model, we

might feel that if we "puzzle" long enough we will

discover a clear, mosaic-like organization of the lexicon

where each item has a clear "place" in a given taxonomy.

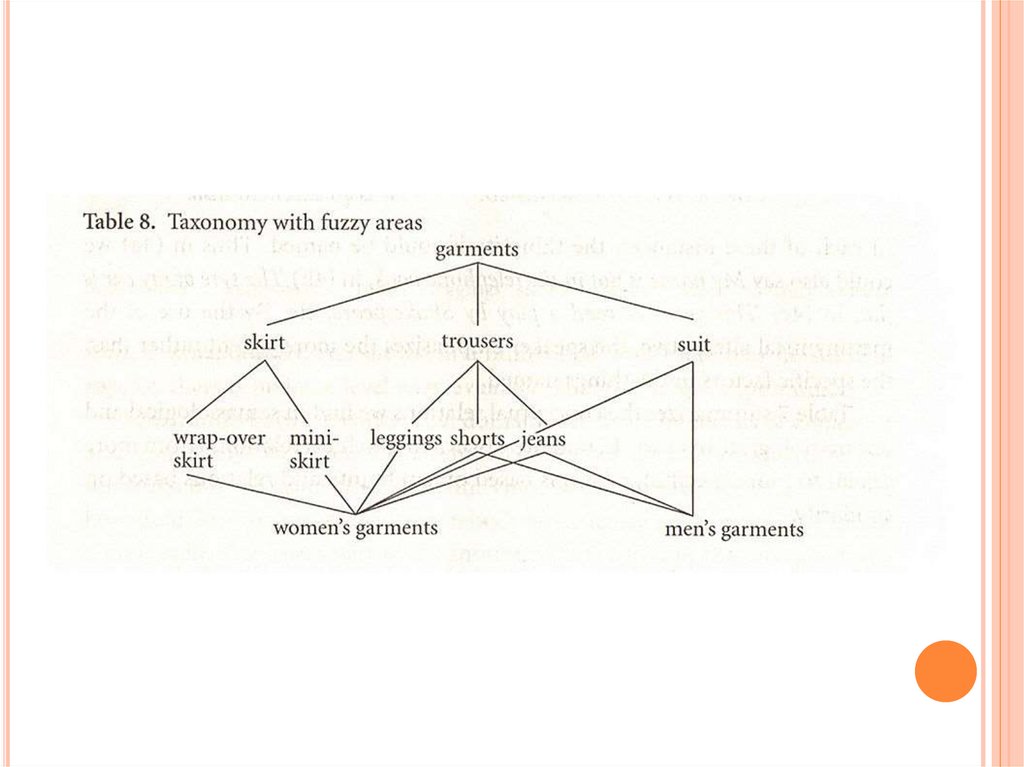

However, there are several reasons to question this

apparent neatness. For one thing, as Table 8 shows,

there are problems of overlap in actual language data:

Since shorts, jeans, and trousers are generally worn by

both men and women, the taxonomy in Table 8 shows

overlapping areas if women's and men's garment criteria

are taken into account.

17.

18.

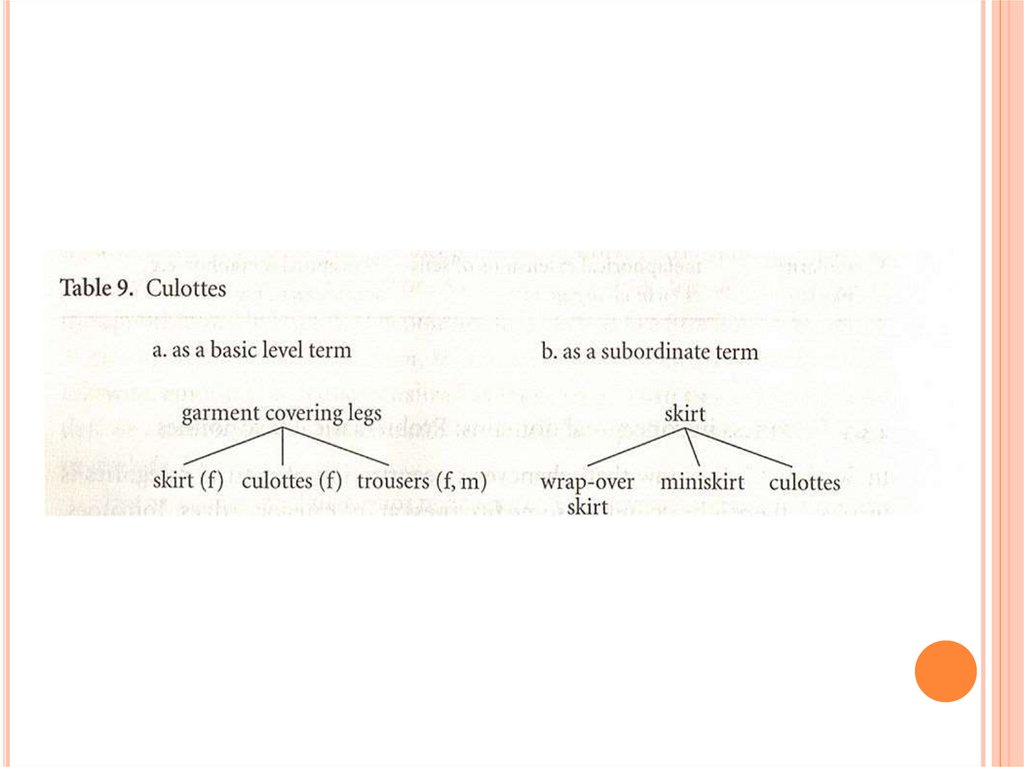

Another problem is that it is not always possible todecide exactly at which level one should place a

lexical item in the hierarchy.

A detailed analysis of clothing terms provided the

following problem: At which level of the taxonomy in

Table 8 would the item culottes (see Figure 2 on

page 39) have to be placed? Is it a word at the more

generalized, higher end of the taxonomy, alongside

"trousers" and "skirt", that is, as a basic level term

(Table 9a), or do culottes belong one level below

these terms as a subordinate category, at the more

specific level (Table 9b)?

19.

20. Conceptual metonymy

CONCEPTUAL METONYMYThe links between conceptual domains are made by

means of metaphor and metonymy.

A conceptual metonymy names one aspect or element

in a conceptual domain while referring to some other

element which is in a contiguity relation with it. The

following instances are typical of conceptual

metonymy.

21.

Основу концептуальной метонимиисоставляет процесс метонимического

проецирования, осуществляемый в пределах

одной идеализированной когнитивной

модели. Опираясь на концепцию З.

Ковечеша и Г. Раддена (Kövecses, 1998), мы

рассматриваем метонимию как когнитивный

процесс, в котором один концепт-источник

обеспечивает ментальный доступ к другому

концепту-цели в пределах одного домена,

или идеализированной когнитивной модели

(ИКМ).

22.

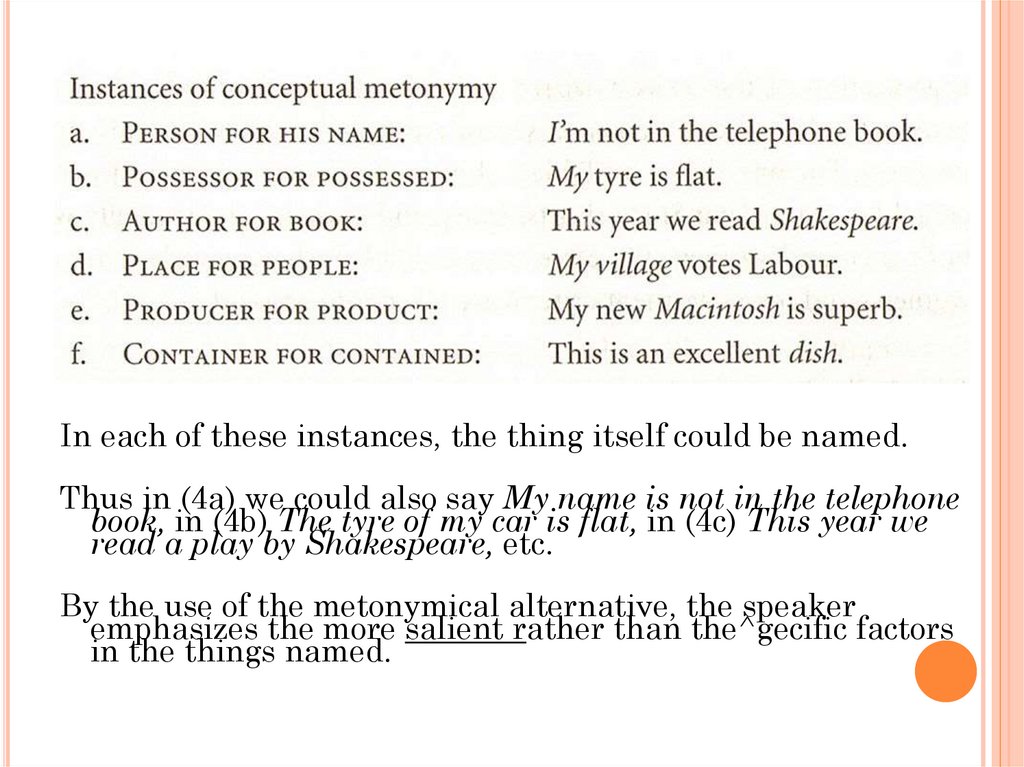

In each of these instances, the thing itself could be named.Thus in (4a) we could also say My name is not in the telephone

book, in (4b) The tyre of my car is flat, in (4c) This year we

read a play by Shakespeare, etc.

By the use of the metonymical alternative, the speaker

emphasizes the more salient rather than the^gecific factors

in the things named.

23. а) Источник ЧАСТЬ → цель ЦЕЛОЕ (т.е. проецирование части на целое):

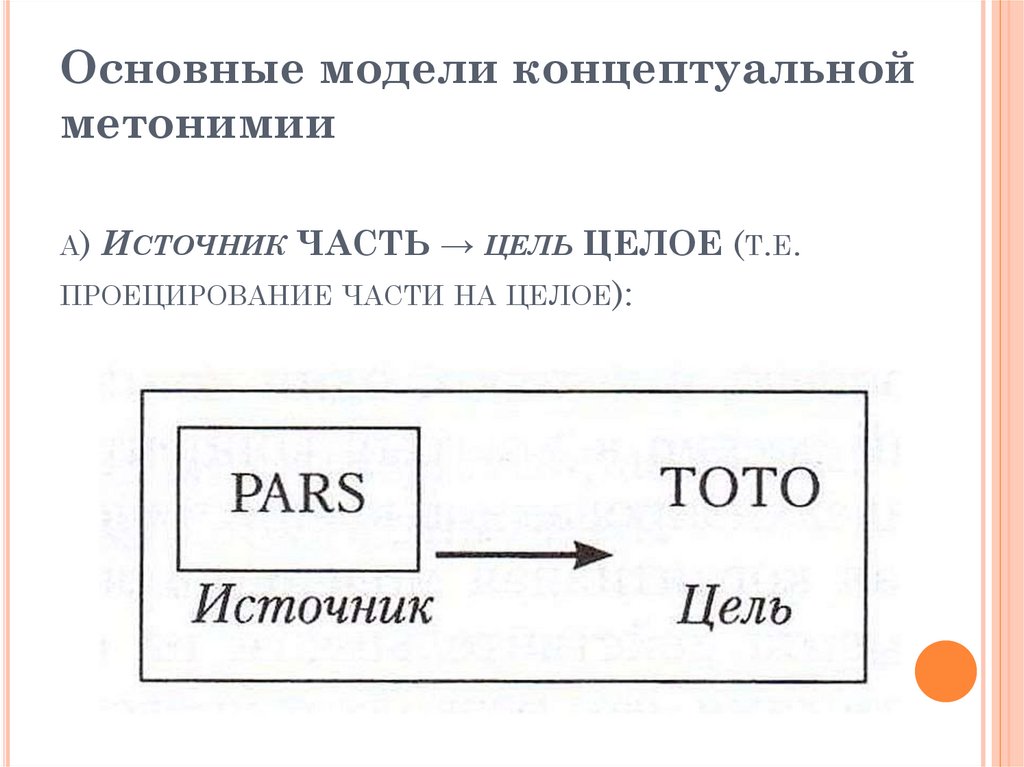

Основные модели концептуальнойметонимии

А) ИСТОЧНИК ЧАСТЬ → ЦЕЛЬ ЦЕЛОЕ (Т.Е.

ПРОЕЦИРОВАНИЕ ЧАСТИ НА ЦЕЛОЕ):

24.

Например,ИКМ “Категория и ее признак”, основанная на

проекции ПРИЗНАК-ОБЪЕКТ, пропозиционально

представленной как ЧАСТЬ ОТНОСИТСЯ К ЦЕЛОМУ:

tube - a can (or bottle) of beer or lager [from the tubular

shape of a can or bottle], где в качестве метонимического

источника выступает визуальный признак формы.

Другими примерами подобной проекции могут служить

ИКМ “Категория и ее члены”: bomb – nuclear weapons

and the potential threat they impose (метоним ЧЛЕН

КАТЕГОРИИ - КАТЕГОРИЯ); ИКМ “Событие”: sick-out

- an organized absence of employees from their jobs on the

pretext of being sick, to avoid the legal penalties that may

result from a formal strike, где физическое состояние

(болезнь) как предлог прогула служащих выступает

частью целого сценария “Забастовка (нового типа)”

(метоним ЧАСТЬ СЦЕНАРИЯ - ЦЕЛЫЙ СЦЕНАРИЙ).

25.

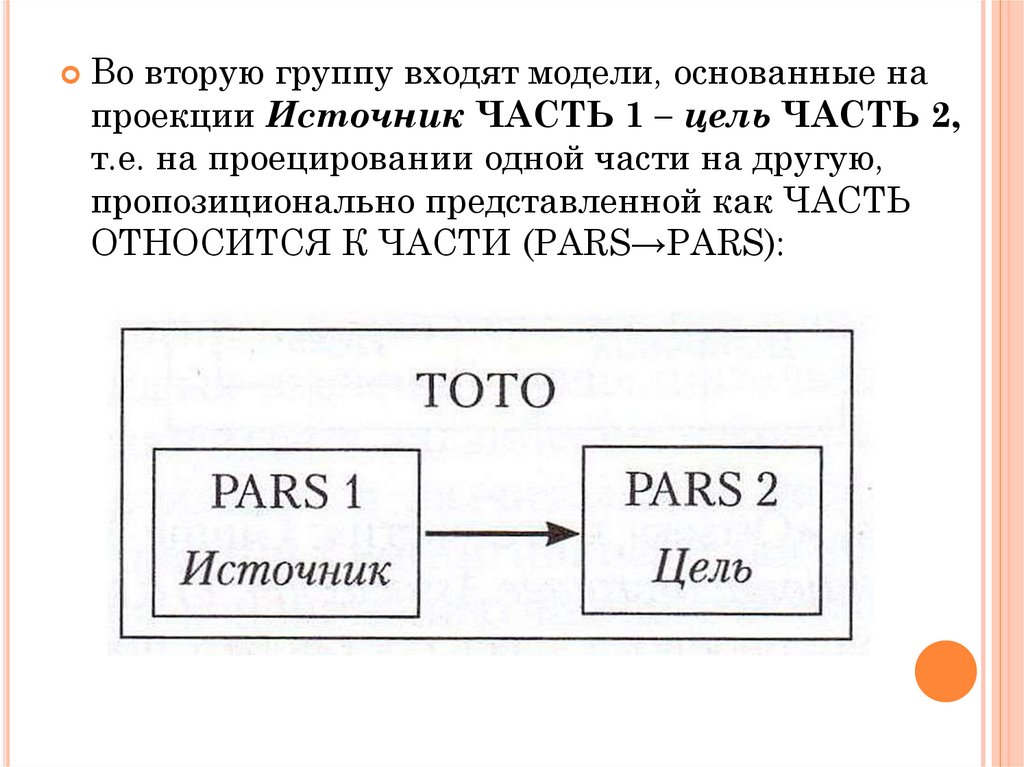

Во вторую группу входят модели, основанные напроекции Источник ЧАСТЬ 1 – цель ЧАСТЬ 2,

т.е. на проецировании одной части на другую,

пропозиционально представленной как ЧАСТЬ

ОТНОСИТСЯ К ЧАСТИ (PARS→PARS):

26.

К примеру,ИКМ “Каузация”, базирующаяся на проекции

ПРИЧИНА-СЛЕДСТВИЕ: slim –AIDS, где

следствие предстает в виде признака - худобы,

вызванной заболеванием СПИД. Сюда же

относятся ИКМ “Функциональные отношения”

(plastic money – credit cards (метоним

ФУНКЦИЯ - СУБЪЕКТ), где с помощью единицы

“пластиковые деньги” на передний план

выдвигается функционирование кредитной

пластиковой карточки как денежного средства);

ИКМ “Отношения обладания” (freebee – 1)

something obtained free of charge, smth gratis; 2)

one who gets or gives smth free of charge (метоним

ОБЛАДАЕМОЕ - ОБЛАДАТЕЛЬ)) и другие ИКМ.

27.

Все рассмотренные единицы образованы врезультате одноступенчатой метонимической

проекции и, как показал анализ, развитие значения

происходит в пределах метонима в составе одной

ИКМ.

Однако среди новых слов встречается немало

единиц вторичной номинации, которые

представляют собой так называемую “двойную”

метонимию.

Анализ неологизма acrylic – 1) acrylic resin; 2) a paint

made with an acrylic resin as the Источник, used

especially in art; 3) a painting done with acrylics.

Представим процесс развития значения в

упрощенном виде: acrylic resin → a paint → a

painting, что схематизируется следующим образом:

28.

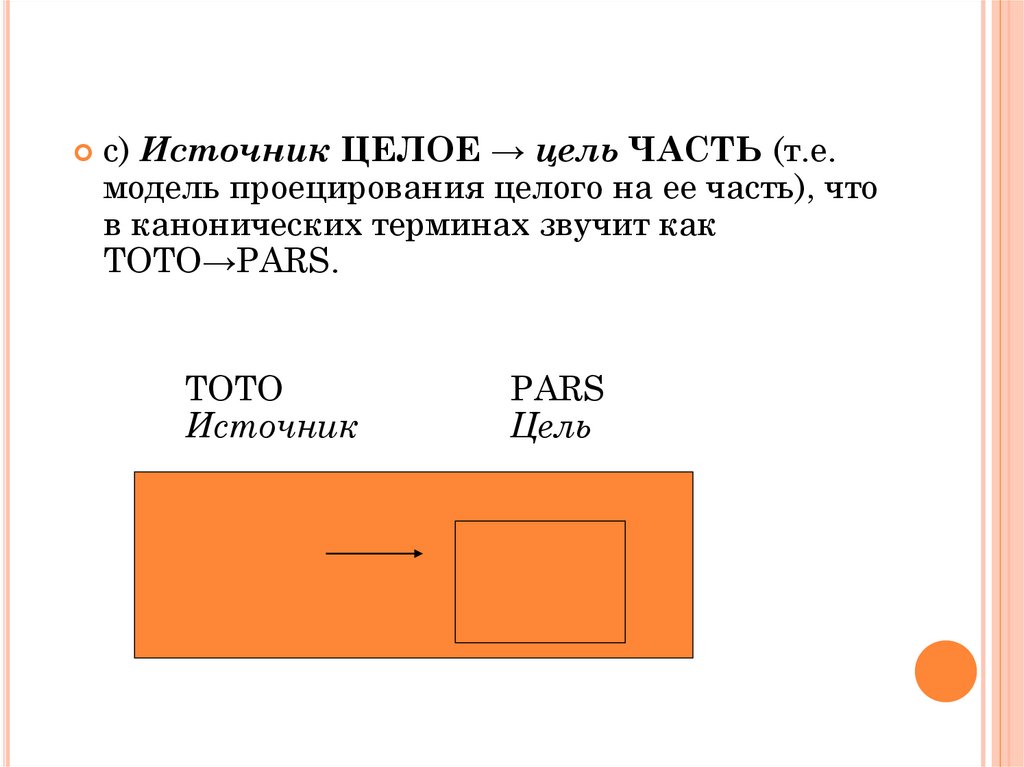

c) Источник ЦЕЛОЕ → цель ЧАСТЬ (т.е.модель проецирования целого на ее часть), что

в канонических терминах звучит как

TOTO→PARS.

TOTO

Источник

PARS

Цель

29.

Например,ИКМ “Объект и его части”:

Ginnie Mae – 1) nickname for the Government National Mortgage

Association; 2) a stock certificate used by this agency.

Основу переноса здесь составляет проекция ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ ПРОДУКТ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ. Ее концептуальный каркас

формирует пропозиция ЦЕЛОЕ ОТНОСИТСЯ К ЧАСТИ,

которая специфицируется в виде указанной проекцииметонима, входящего в состав более крупной ИКМ.

Под метонимом мы понимаем концептуальную единицу,

встроенную в наше сознание и определяющую регулярное

направление изменения значения по метонимическому типу.

Таким образом, концептуальный каркас нового

метонимического значения формируется на основе

неоперационных и операционных когнитивных моделей в

виде цепочки “пропозиция – метоним - ИКМ”

30. Conclusions

CONCLUSIONSThe main levels of categorization are:

1. Superordinate

2. Basic

3. Subordinate

The basic principle underlying categorization is the

notion of class inclusion

The superordinate class includes all items on the basic

and subordinate level

31. Conclusions

CONCLUSIONSThe links between conceptual domains are made by

means of metaphor and metonymy.

A conceptual metonymy names one aspect or

element in a conceptual domain while referring to

some other element which is in a contiguity relation

with it.

biology

biology