Similar presentations:

Chapter Eighteen. Externalities, Open Access, and Public Goods

1.

ChapterEighteen

Externalities,

Open Access,

and Public Goods

2.

Externalities, Open Access, and PublicGoods

• In this chapter, we examine six main

topics

– Externalities

– The inefficiency of competition with

externalities

– Market structure and externalities

– Allocating property rights to reduce

externalities

– Open-access common property

– Public goods

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

3.

Externalities• Externality

– The direct effect of the actions of a

person or firm on another person’s wellbeing or a firm’s production capability

rather than an indirect effect through

changes in prices.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

4.

Externalities• Externalities may either help or harm

others.

• An externality that harms someone is

called a negative externality.

• A positive externality benefits others.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

5.

The inefficiency of competition withexternalities

• Competitive firms and consumers do

not have to pay for the harms of their

negative externalities, so they create

excessive amounts.

• Because producers are not

compensated for the benefits of a

positive externality, too little of such

externalities is produced.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

6.

The inefficiency of competition withexternalities

• Private cost

– The cost of production only, not

including externalities

• Social cost

– The private cost plus the cost of the

harms from externalities

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

7.

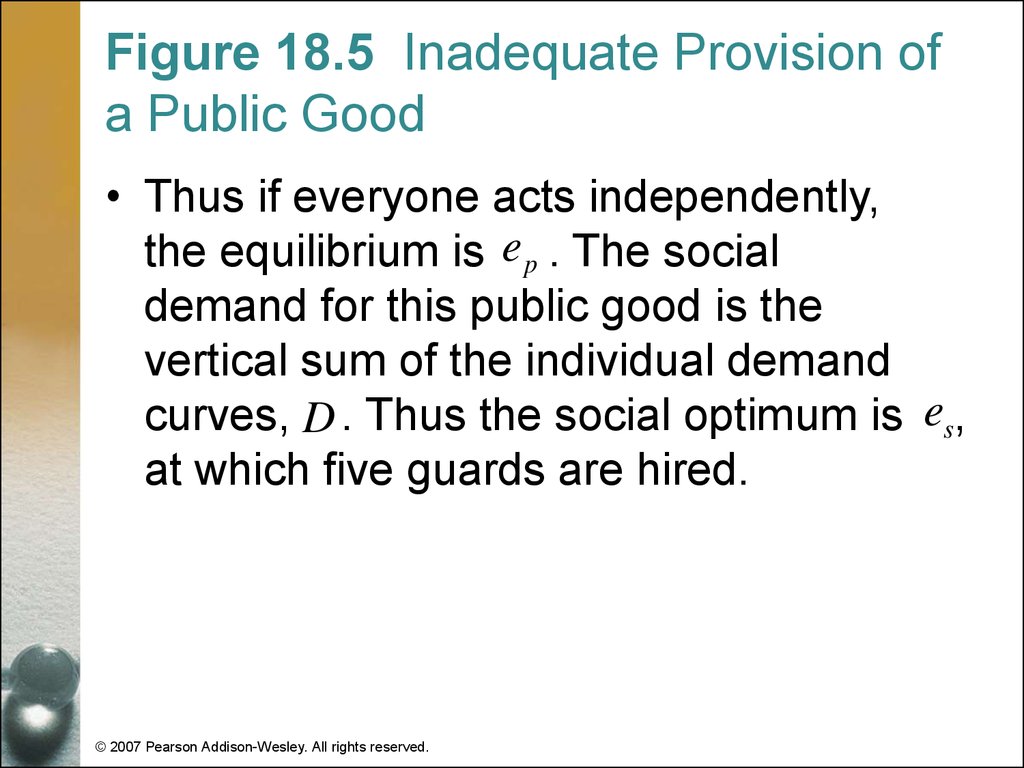

Supply-and-Demand Analysis• We use a supply-and-demand diagram

to illustrate that a competitive market

produces excessive pollution because

the firms’ private cost is less than their

social cost.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

8.

Figure 18.1 Welfare Effects ofPollution in a Competitive Market

• The competitive equilibrium, ec , is

determined by the intersection of the

demand curve and the competitive

supply or private marginal cost

curve, MC p , which ignores the cost of

pollution.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

9.

Figure 18.1 Welfare Effects ofPollution in a Competitive Market

• The social optimum, es , is at the

intersection of the demand curve and

the social marginal cost curve,

MC s MC p MC g , where MC g is the

marginal cost of the pollution (gunk).

Private producer surplus is based on

curve, and social producer surplus is

s

MC

based on the

curve.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

10.

Figure 18.1 Welfare Effects ofPollution in a Competitive Market

450

MC s = MC p + MC g

A

MC p

es

ps = 282

B

C D

H

pc = 240

198

F

84

E

G

ec

MC p

MC g

MC g

30

Demand

0

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

Qs = 84 Qc = 105

225

Q, Tons of paper per day

18–10

11.

Supply-and-Demand Analysis• The figure illustrates two main results

with respect to negative externalities.

• First, a competitive market produces

excessive negative externalities.

• Second, the optimal amount of pollution

is greater than zero.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

12.

Reducing Externalities• Because competitive markets produce

too many negative externalities,

government intervention may provide a

social gain.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

13.

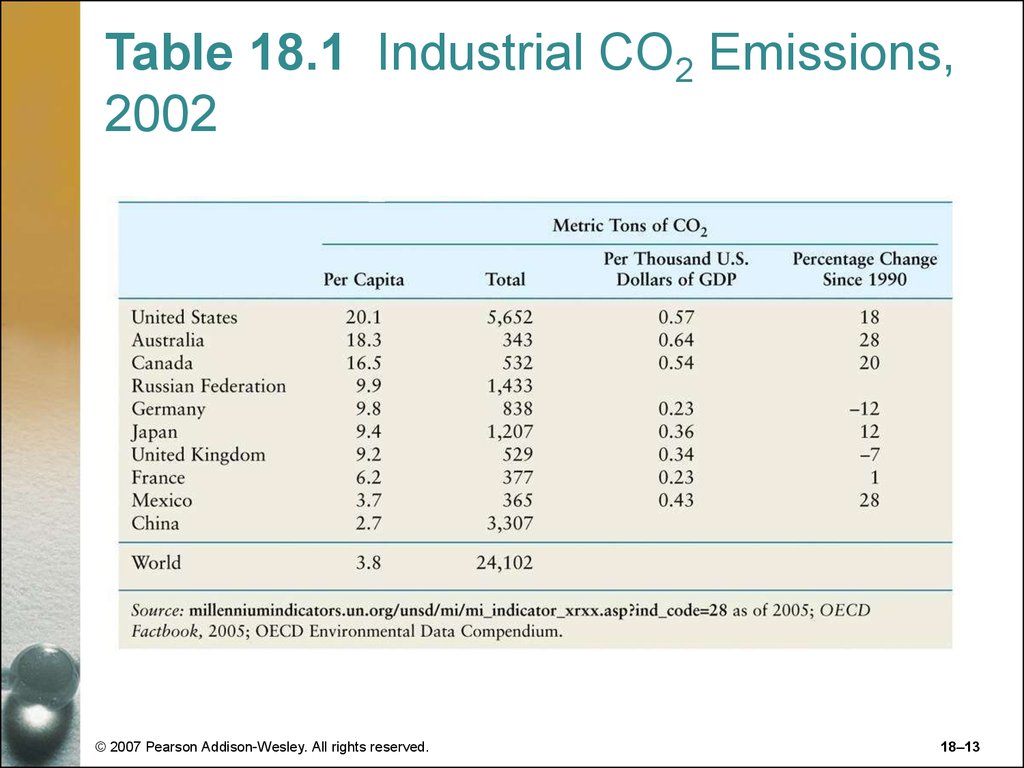

Table 18.1 Industrial CO2 Emissions,2002

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18–13

14.

Reducing Externalities• If a government has sufficient

knowledge about pollution damage, the

demand curve, costs, and the

production technology, it can force a

competitive market to produce the

social optimum.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

15.

Reducing Externalities• A governmental limit on the amount of

air or water pollution that may be

released is called an emission standard.

A tax on air pollution is called an

emissions fee, and a tax on discharges

into the air or waterways is an effluent

charge.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

16.

Reducing Externalities• Internalize the externality

– To bear the cost of the harm that one

inflicts on others (or to capture the

benefit that one provides to others)

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

17.

Figure 18.2 Taxes to ControlPollution

• Placing a tax on the firms equal to the

g

harm the gunk, t (Q) MC , causes

them to internalize the externality, so

their private marginal cost is the same

s

as the social marginal cost, MC . As a

result, the competitive after-tax

equilibrium is the same as the social

optimum, es .

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18.

Figure 18.2 Taxes to ControlPollution

• Alternatively, applying a specific tax of

$84 per ton of paper, which is the

marginal harm from the gunk at Qs 84 ,

also results in the social optimum.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

19.

Figure 18.2 Taxes to ControlPollution

450

MC s = MC p + t (Q)

MC p +

es

ps = 282

MC p

= 84

MC p

= 198

MC g

MC g = 84

Demand

0

Qs = 84

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

225

Q, Tons of paper per day

18–19

20.

Cost-Benefit Analysis• By using a cost-benefit analysis, we

obtain another interpretation of the

pollution problem in terms of the

marginal cost and benefit of the

pollution itself.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

21.

Cost-Benefit Analysis• Welfare is maximized by reducing

output and pollution until the marginal

benefit from less pollution equals the

marginal cost of less output.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

22.

Figure 18.3 Cost-Benefit Analysisof Pollution

a) The benefit curve reflects the reduction in

harm from pollution as the amount of gunk

falls from the competitive level. The cost of

reducing the amount of gunk is the fall in

output, which reduces consumer surplus

and private producer surplus. Welfare is

maximized at 84 tons of paper and 84 units

of gunk, the quantities at which the

difference between the benefit and cost

curves, the net benefit, is greatest.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

23.

Figure 18.3 Cost-Benefit Analysisof Pollution

b) The net benefit is maximized where

the marginal benefit, MB , which is the

slope of the benefit curve, equals the

marginal cost, MC , the slope of the

cost curve.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

24.

Figure 18.3Cost-Benefit

Analysis

of Pollution

(a) Cost and Benefit

Cost: less paper

4,000

Benefit: less gunk

2,000

0

105

Maximum

net

benefit

84

63

(b) Marginal Cost and Marginal Benefit

Q, Tons of paper per day

G, Units of gunk per day

MC

105

84

MB

0

105

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

84

Q, Tons of paper per day

G, Units of gunk per day

18–24

25.

Market Structure and Externalities• Two of our main results concerning

competitive markets and negative

externalities—that too much pollution is

produced and that a tax equal to the

marginal social cost of the externality

solves the problem—do not hold for

other market structures.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

26.

Monopoly and Externalities• Although the competitive market with an

externality always produces more

output than the social optimum, a

monopoly may produce more than, the

same as, or less than the social

optimum.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

27.

Monopoly and Externalities• Which effect dominates depends on the

elasticity of demand for the output and

on the extent of the marginal damage

the pollution causes.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

28.

Monopoly Versus Competitive Welfarewith Externalities

• In the absence of externalities, welfare

is greater under competition than under

an unregulated monopoly.

• However, with an externality, welfare

may be greater with monopoly than with

competition.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

29.

Figure 18.4 Monopoly, Competition,and Social Optimum with Pollution

• At the competitive equilibrium, ec , more

is produced than at the social

optimum, es . As a result, the deadweight

loss in the competitive market is D . The

monopoly equilibrium, em , is determined

by the intersection of the marginal

revenue and the private marginal

p

cost, MC , curves.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

30.

Figure 18.4 Monopoly, Competition,and Social Optimum with Pollution

• The social welfare (based on the

s

marginal social cost, MC , curve) under

monopoly is A B. Here the deadweight

loss of monopoly, C , is less than the

deadweight loss under competition, D .

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

31.

Figure 18.4 Monopoly, Competition,and Social Optimum with Pollution

450

MC s = MC p + MC g

et

330

310

282

em

es

A

B

MC p

D

C

ec

240

MC g

30

MR

0

60 70

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

84

105

Demand

225

Q, Tons of paper per day

18–31

32.

Taxing Externalities in NoncompetitiveMarkets

• Trying to solve a negative externality

problem is more complex in a

noncompetitive market than in a

competitive market.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

33.

Taxing Externalities in NoncompetitiveMarkets

• To achieve a social optimum in a

competitive market, the government

only has to reduce the externality,

possibly by decreasing output.

• In a noncompetitive market, the

government must eliminate problems

arising from both externalities and the

exercise of market power.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

34.

Allocating Property Rights to ReduceExternalities

• Instead of controlling externalities

directly through emissions fees and

emissions standards, the government

may take an indirect approach by

assigning a property right: an

exclusive privilege to use an asset.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

35.

Allocating Property Rights to ReduceExternalities

• If no one holds a property right for a

good or a bad, the good or bad is

unlikely to have a price.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

36.

Allocating Property Rights to ReduceExternalities

• For many bads, such as pollution, and

for some goods, property rights are not

clearly defined. No one has exclusive

property rights to the sir we breathe.

Because of this lack of a price, a

polluter’s private marginal cost of

production is less than the full social

marginal cost.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

37.

Coase Theorem• According to the Coase Theorem

(Coase, 1960), the optimal levels of

pollution and output can result from

bargaining between polluters and their

victims if property rights are clearly

defined.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

38.

Table 18.2 (a,b) Property Rights andBargaining

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18–38

39.

Table 18.2 (c) Property Rights andBargaining

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18–39

40.

Coase TheoremIf there are no impediments to

bargaining, assigning property rights

results in the efficient outcome at which

joint profits are maximized.

Efficiency is achieved regardless of who

receives the property rights.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

41.

Coase TheoremWho gets the property rights affects the

income distribution. The property rights

are valuable. The party with the

property rights may be compensated by

the other party.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

42.

Problems with the Coase Approach• First, if transaction costs are very high,

it might not pay for the two sides to

meet.

• Second, if firms engage in strategic

bargaining behavior, an agreement may

not be reached.

• Third, if either side lacks information

about the costs or benefits or reducing

pollution, a nonefficient outcome may

occur.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

43.

Markets for Pollution• If high transaction costs preclude

bargaining, we may be able to

overcome this problem by using a

market, which facilitates exchanges

between individuals.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

44.

Markets for Pollution• Under this cap and trade system, the

government gives firms permits, each of

which confers the right to create a

certain amount of pollution. Each firm

may use its permits or sell them to other

firms.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

45.

Markets for Pollution• Bu using a market, the government

does not have to collect this type of

detailed information to achieve

efficiency. Its only decision concerns

what total amount of pollution to allow.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

46.

Open-Access Common Property• Open-Access Common Property

– Resources to which everyone has free

access

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

47.

Overuse of Open-Access CommonProperty

Because people do not have to pay to

use open-access common property

resources, they are overused.

e.g. 1. Common Pools.

2. The Internet.

3. Roads

4. Fisheries.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

48.

Solving the Commons Problem• Government Regulation of Commons

– Overuse of a common resource occurs

because individuals do not bear the full

social cost. However, by applying a tax

or fee equal to the externality harm that

each individual imposes on others, a

government forces each person to

internalize the externality.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

49.

Solving the Commons Problem• Government Regulation of Commons

– Alternatively, the government can

restrict access to the commons. One

typical approach is to grant access on a

first-come, first-served basis.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

50.

Solving the Commons Problem• Assigning Property Rights

– An alternative approach to resolving the

commons problem is to assign private

property rights.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

51.

Public Goods• Public Good

– A commodity or service whose

consumption by one person does not

preclude others from also consuming it

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

52.

Types of GoodsTable 18.3 Rivalry and Exclusion

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18–52

53.

Markets for Public Goods• Markets for public goods exist only if

nonpurchasers can be excluded from

consuming them.

• Markets do not exist for nonexclusive

public goods.

• If the government does not provide a

nonexclusive public good, no one

provides it.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

54.

Demand for Public Goods• Because a public good lacks rivalry,

many people can get pleasure from the

same unit of output. As a consequence,

the social demand curve or willingnessto-pay curve for a public good is the

vertical sum of the demand curves of

each individual.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

55.

Figure 18.5 Inadequate Provision ofa Public Good

• Security guards protect both tenants of

the mall. If each guard costs $10 per

hour, the television store, with

demand D1, is willing to hire four guards

per hour. The ice-cream parlor, with

2

D

demand , is not willing to hire any

guards.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

56.

Figure 18.5 Inadequate Provision ofa Public Good

• Thus if everyone acts independently,

the equilibrium is e p . The social

demand for this public good is the

vertical sum of the individual demand

curves, D . Thus the social optimum is es,

at which five guards are hired.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

57.

Figure 18.5 Inadequate Provision ofa Public Good

25

D

18

D1

13

ep

es

Supply, MC

10

8

7

D2

3

2

0

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

4

5

7

9

Guards per hour

18–57

58.

Free Riding• Many people are unwilling to pay for

their share of a public good. They try to

get others to pay for it, so they can free

ride: benefit from the actions of others

without paying.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

59.

Table 18.4 Private Payments for aPublic Good

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18–59

60.

Free Riding• In each of these games, the Nash

equilibrium is for neither store to hire a

guard because of free riding. The

nonoptimal outcome occurs for the

same reason as in other prisoners’

dilemma games: The stores don’t do

what is best for them collectively when

they act independently.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

61.

Reducing Free Riding• Governmental or other collective actions

can reduce free riding.

• Methods that may be used include

social pressure, merges, compulsion,

and privatization.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

62.

Valuing Public Goods• To ensure that a nonexclusive public

good is provided, a government usually

produces it or compels others to do so.

Issues that a government faces in

providing such a public good include

whether to provide it at all and, if so,

how much to provide.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

63.

Table 18.5 Voting on $300 Traffic Signals© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

18–63

64.

Valuing Public Goods• The problem with yes-no votes is that

they ignore the intensity of preferences.

• Thus such majority voting fails to value

the public good fully and hence does

not guarantee that it is efficiently

provided.

© 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

economics

economics