Similar presentations:

Narrative Stylistics

1. NARRATIVE STYLISTICS

• Narrative discourse provides a way ofrecapitulating felt experience by matching up

patterns of language to a connected series

of events. In its most minimal form, a

narrative comprises two clauses which are

temporally ordered, such that a change in

their order will result in a change in the

way we interpret the assumed chronology

of the narrative events.

2.

• For example, the two narrative clauses in atemporal progression between the two

actions described:

• John dropped the plates, and Janet laughed

suddenly.

• What will happen if we reverse the clauses?

3.

• Reversing the clauses to form ‘Janetlaughed suddenly, and John dropped the

plates’ would invite a different interpretation:

that is, that Janet’s laughter not only

preceded but actually precipitated John’s

misfortune.

4.

• Mostnarratives, whether those of

canonical

prose

ction

or

of the

spontaneous stories of everyday social

interaction, have rather more to offer than

just two simple temporally arranged

clauses.

5.

• Narrative requires development elaboration,embellishment; and it requires a sufficient

degree of stylistic ourish to give it an

imprint of individuality or personality.

Stories narrated without that ourish will

often feel at and dull.

6.

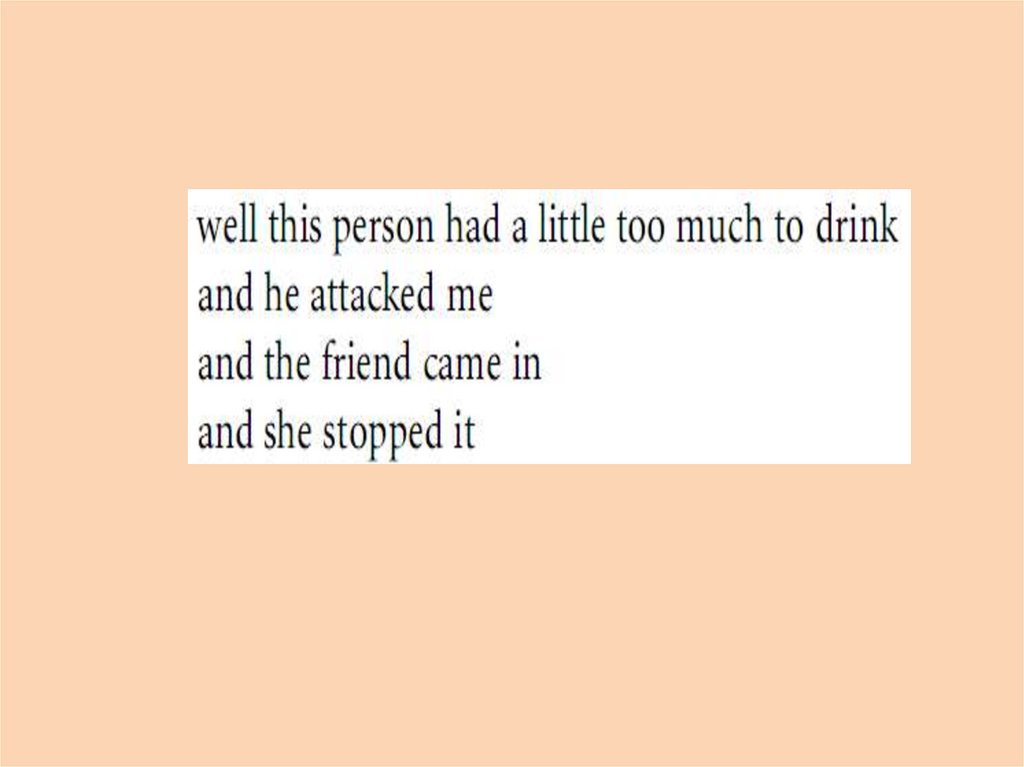

• On this issue, the sociolinguistWilliam Labov has argued that

narratives require certain essential

elements of structure which, when

absent, render the narrative ‘illformed’. He cites the following

attested story as an illustration:

7.

8.

• This story, which is really only a skeleton of afully formed narrative, was told by an adult

informant who had been asked to recollect an

experience where they felt they had been in

real danger. True, the story does satisfy the

minimum criterion for narrative in that it

comprises temporally connected clauses, but

it also lacks a number of important elements

which are important to the delivery of a

successful narrative.

9.

• A listener might legitimately ask, for instance,about exactly where and when this story took

place. And who was involved in the story?

That is, who was the ‘person’ who had too

much to drink and precisely whose friend

was ‘the friend’ who stopped the attack?

How, for that matter, did the storyteller

come to be in the same place as the

antagonist? And is the friend’s act of

stopping the assault the nal action of the

story?

10.

• Clearly, much is missing from thisnarrative. As well as lacking suf cient

contextualisation, it offers little sense of

nality. It also lacks any dramatic or

rhetorical embellishment, and so risks

attracting a rebuke like ‘so what?’ from

an interlocutor.

11.

• It is common for much work instylistics and narratology to make a

primary distinction between two basic

components of narrative: narrative plot

and narrative discourse.

12.

• The term plot is generallyunderstood to refer to the

abstract storyline of a narrative; that

is, to the sequence of elemental,

chronologically ordered events which

create the ‘inner core’ of a

narrative.

13.

• Narrative discourse, by contrast, incompassesthe manner or means by which that plot is

narrated. Narrative discourse, for example, is

often characterised by the use of stylistic

devices such, for example, ashback which

serves to disrupt the basic chronology of the

narrative’s plot.

14.

• Thus, narrative discourse represents therealised text, the palpable piece of

language which is produced by a storyteller in a given interactive context.

15.

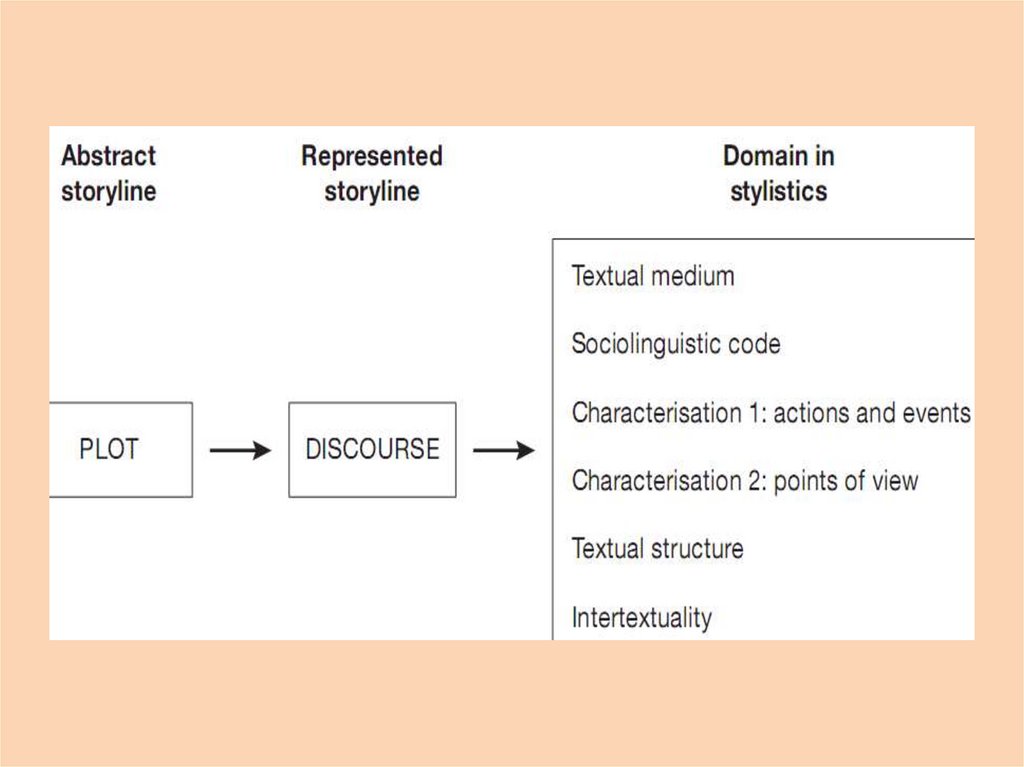

• The next step involves sorting outthe various stylistic elements which

make up narrative discourse. To help

organise narrative analysis into

clearly demarcated areas of study

the following model can be used:

16.

17.

• The rst of the six is textual medium. Thisrefers simply to the physical channel of

communication through which a story is

narrated. Two common narrative media are

lm and the novel, although various other

forms are available such as the ballet, the

musical or the strip cartoon.

18.

• Sociolinguisticcode

expresses

through language the historical,

cultural and linguistic setting which

frames a narrative. It locates the

narrative in time and place by

drawing upon the forms of

language

which

re ect

this

sociocultural context.

19.

• Sociolinguisticcode

encompasses,

amongst other things, the varieties of

accent and dialect used in a narrative,

whether they be ascribed to the narrator

or to characters within the narrative,

although the concept also extends to the

social and institutional registers of

discourse deployed in a story.

20.

• The rst of the two characterization elements,actions

and

events, describes how the

development of character precipitates and

intersects with the actions and events of a story.

It accounts for the ways in which the narrative

intermeshes with particular kinds of semantic

process, notably those of ‘doing’, ‘thinking’ and

‘saying’, and for the ways in which these

processes are attributed to characters and

narrators. This category approaches narrative

within the umbrella concept of ‘style as choice’.

21.

• The second category of narrativecharacterisation, point of view, explores

the relationship between mode of

narration

and

a

character’s or

narrator’s ‘point of view’.

22.

• Mode of narration speci es whether thenarrative is relayed in the rst person, the

third person or even the second person,

while point of view stipulates whether the

events of story are viewed from the

perspective of a particular character or from

that of an omniscient narrator, or indeed from

some mixture of the two.

23.

• The way speech and thoughtprocesses are represented in

narrative is also an important

index of point of view.

24.

• Textual structure accounts for the wayindividual narrative units are arranged and

organised in a story. A stylistic study of

textual structure may focus on large-scale

elements of plot or, alternatively, on more

localised features of story’s organisation;

similarly, the particular analytic models

used may address broad-based aspects of

narrative coherence or they may examine

narrower aspects of narrative cohesion in

organisation.

25.

• The term intertextuality, the sixth narrativecomponent, is reserved for the technique

of ‘allusion’. Narrative ction, like all writing,

does not exist in a social and historical

vacuum, and it often echoes other texts

and

images

either

as

‘implicit’

intertextuality or as ‘manifest’ intertextuality.

26. TYPES OF NARRATION IN CREATIVE PROSE

• A work of creative prose is never homogeneous asto the form and essence of the information it

carries. Both very much depend on the viewpoint

of the addresser, as the author and his personages

may offer different angles of perception of the

same object. Naturally, it is the author who

organizes this effect of polyphony, but we, the

readers, while reading the text, identify various

views with various personages, not attributing

them directly to the writer.

27.

• The latter's views and emotions are mostexplicitly expressed in the author's speech (or the

author's narrative).

• The author's narrative supplies the reader with

direct information about the author's preferences

and objections, beliefs and contradictions, i.e.

serves the major source of shaping up the author's

image.

28.

• In contemporary prose, in an effort to make his writingmore plausible, to impress the reader with the effect of

authenticity of the described events, the writer entrusts

some fictitious character (who might also participate in

the narrated events) with the task of story-telling. The

writer himself thus hides behind the figure of the

narrator, presents all the events of the story from the

latter's viewpoint and only sporadically emerges in the

narrative with his own considerations, which may

reinforce or contradict those expressed by the narrator.

This form of the author's speech is called entrusted

narrative.

29.

• The structure of the entrusted narrative is much morecomplicated than that of the author's narrative proper, because

instead of one commanding, organizing image of the author, we

have the hierarchy of the narrator's image seemingly arranging the

pros and cons of the related problem and, looming above the

narrator's image, there stands the image of the author, the true and

actual creator of it all, responsible for all the views and evaluations

of the text and serving the major and predominant force of textual

cohesion and unity.

• Entrusted narrative can be carried out in the 1st person singular,

when the narrator proceeds with his story openly and explicitly,

from his own name, as, e.g., in The Catcher in the Rye by J.D.

Salinger, or The Great Gatsby by Sc. Fitzgerald, or All the King's

Men by R.f.Warren.

30.

• The narrative, both the author's and the entrusted,is not the only type of narration observed in

creative prose. A very important place here is

occupied by dialogue, where personages express

their minds in the form of uttered speech. In their

exchange of remarks the participants of the

dialogue, while discussing other people and their

actions, expose themselves too. So dialogue is one

of the most significant forms of the personage's

self-characterization, which allows the author to

seemingly eliminate himself from the process.

31.

• Another form, which obtained a position ofutmost significance in contemporary prose, is

interior speech of the personage, which allows

the author (and the readers) to peep into the inner

world of the character, to observe his ideas and

views. Interior speech is best known in the form

of interior monologue, a rather lengthy piece of

the text (half a page and over) dealing with one

major topic of the character's thinking, offering

causes for his past, present or future actions. Short

insets of interior speech present immediate mental

and emotional reactions of the personage to the

remark or action of other characters.

32.

• The imaginative reflection of mental processes,presented in the form of interior speech, being a part of

the text, one of the major functions of which is

communicative, necessarily undergoes some linguistic

structuring to make it understandable to the readers. In

extreme cases, though, this desire to be understood by

others is outshadowed by the author's effort to portray

the disjointed, purely associative manner of thinking,

which makes interior speech almost or completely

incomprenensible. These cases exercise the so-called

stream-of-consciousness technique which is especially

popular with representatives of modernism in

contemporary literature.

33.

• The last - the fourth - type of narration observed in artisticprose is a peculiar blend of the viewpoints and language

spheres of both the author and the character - represented

(reported) speech. Represented speech serves to show either

the mental reproduction of a once uttered remark, or the

character's thinking. The first case is known as represented

uttered speech, the second one as represented inner speech.

The latter is close to the personage's interior speech in essence,

but differs from it in form: it is rendered in the third person

singular and may have the author's qualitative words, i.e. it

reflects the presence of the author's viewpoint alongside that of

the character, while interior speech belongs to the personage

completely, formally too, which is materialized through the

first-person pronouns and the language idiosyncrasies of the

character.

34.

• The last - the fourth - type of narration observed in artistic prose is apeculiar blend of the viewpoints and language spheres of both the author

and the character - represented (reported) speech. Represented speech

serves to show either the mental reproduction of a once uttered remark, or

the character's thinking. The first case is known as represented uttered

speech, the second one as represented inner speech. The latter is close to

the personage's interior speech in essence, but differs from it in form: it is

rendered in the third person singular and may have the author's qualitative

words, i.e. it reflects the presence of the author's viewpoint alongside that

of the character, while interior speech belongs to the personage completely,

formally too, which is materialized through the first-person pronouns and

the language idiosyncrasies of the character.

literature

literature english

english