Similar presentations:

Focalization in two Mande languages: Mandinka and Soninke

1.

Typological perspectives on focus marking in African languagesParis, May 27, 2021

Focalization in two Mande languages:

Mandinka and Soninke

Denis Creissels

Université Lumière (Lyon 2)

[email protected]

http://deniscreissels.fr

1

2.

1. IntroductionMandinka and Soninke belong to two distinct sub-branches of the Western

branch of the Mande language family. Mandinka has approximately 1.5 million

speakers in the Gambia, Senegal, and Guinea Bissau. It is the westernmost

member of the Manding dialect cluster, whose best-known members are Malian

Bambara and Guinean Maninka. Soninke has approximately 2 million speakers in

Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, and the Gambia. Its closest relatives are Bozo

languages.

This presentation is devoted to focalization in these two Mande languages. In

both languages, focalization involves enclitic focus markers (Mandinka lè, Soninke

`yá) that do not differ in their syntactic properties, but greatly differ in their

morphological interaction with the other elements of the constructions in which

they are involved.

2

3.

2. Some basic information on Mandinka and Soninke morphosyntax (1)The most striking characteristic of verbal clauses in Mandinka and Soninke (and

more generally, in Mande languages) is the extreme rigidity of the typologically

unusual Subject-Object-Verb-Obliques constituent order in verbal clauses, with

a clearcut contrast between core terms preceding the verb and obliques

(standardly expressed as adpositional phrases or adverbs) in post-verbal

position.

With the exception of some types of adjuncts, noun phrases or adpositional

phrases cannot occur in topic position (on the left edge of the clause) without

being resumed by a pronoun occupying the position they would occupy within

the clause if they were not topicalized.

Pronouns occupy the same positions as lexical noun phrases, and there is no

indexation of either subjects or objects. Null subjects or objects are not

allowed: with the exception of the subject slot in imperative clauses, whatever

the discursive context, the subject slot in independent intransitive clauses and

the subject and object slots in independent transitive clauses cannot be left

empty.

3

4.

3. Some basic information on Mandinka and Soninke morphosyntax (2)In Mandinka and Soninke, the inflection of verbs in the role of nucleus of

independent verbal clauses is very reduced. The expression of grammaticalized

TAM values and of polarity mainly relies on auxiliary-like elements called

PREDICATIVE MARKERS in the Mandeist tradition.

Predicative markers are portmanteau morphemes encoding grammaticalized

aspectual and modal distinctions and expressing polarity. They immediately

follow the subject phrase, which means that, in transitive clauses, they are

separated from the verb by the object phrase.

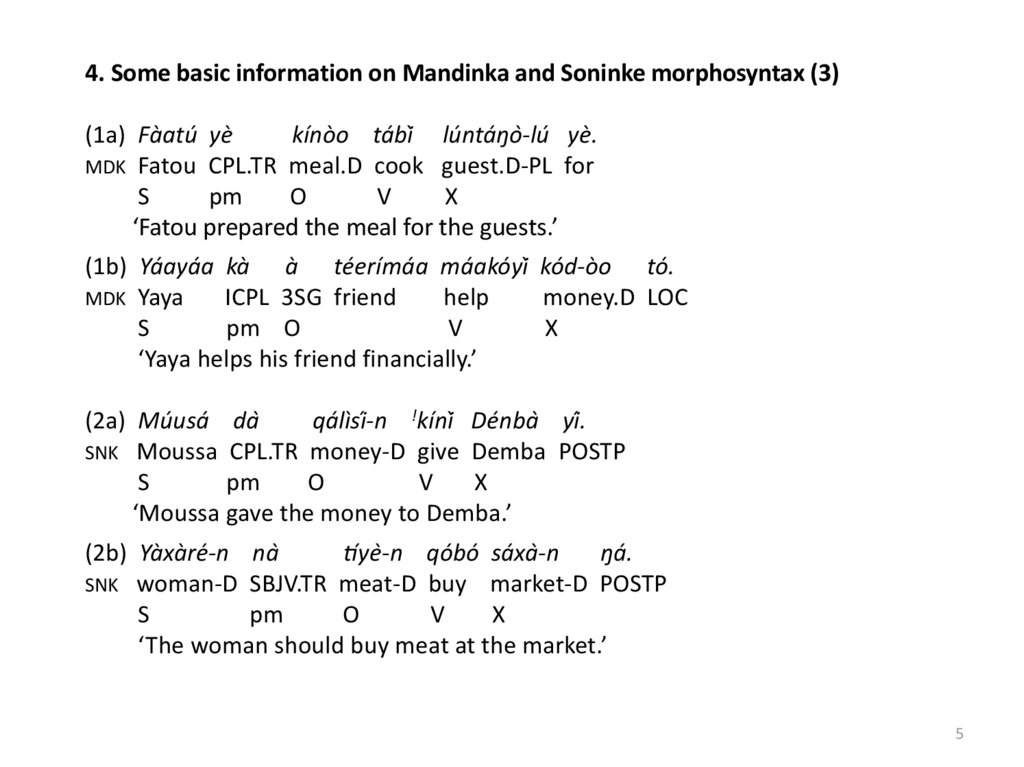

Examples (1) and (2) on next slide illustrate transitive clauses in Mandinka and

Soninke. A particularity shared by Mandinka and Soninke is that, in assertive

and interrogative transitive clauses, there is always an overt predicative marker

between the subject phrase and the object phrase.

4

5.

4. Some basic information on Mandinka and Soninke morphosyntax (3)(1a) Fàatú yè

kínòo tábì lúntáŋò-lú yè.

MDK Fatou CPL.TR meal.D cook guest.D-PL for

S

pm

O

V

X

‘Fatou prepared the meal for the guests.’

(1b) Yáayáa kà à téerímáa máakóyì kód-òo tó.

MDK Yaya

ICPL 3SG friend

help

money.D LOC

S

pm O

V

X

‘Yaya helps his friend financially.’

(2a) Múusá dà

qálìsí-n !kínì Dénbà yí.

SNK Moussa CPL.TR money-D give Demba POSTP

S

pm

O

V

X

‘Moussa gave the money to Demba.’

(2b) Yàxàré-n nà

tíyè-n qóbó sáxà-n

ŋá.

SNK woman-D SBJV.TR meat-D buy market-D POSTP

S

pm

O

V

X

‘The woman should buy meat at the market.’

5

6.

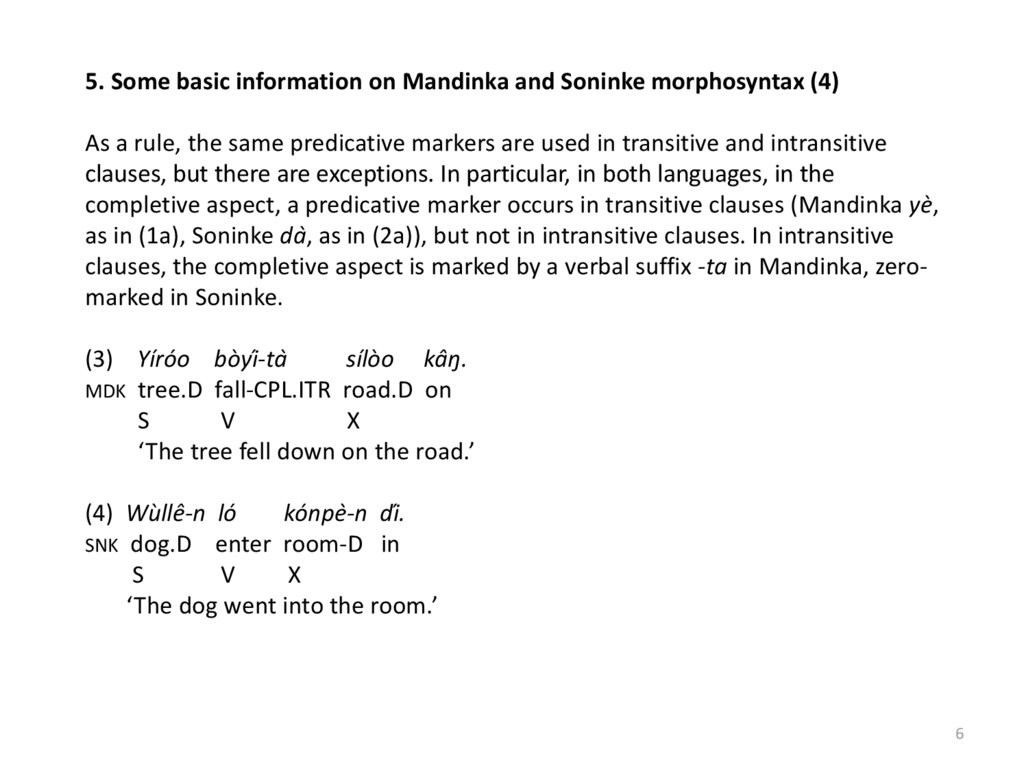

5. Some basic information on Mandinka and Soninke morphosyntax (4)As a rule, the same predicative markers are used in transitive and intransitive

clauses, but there are exceptions. In particular, in both languages, in the

completive aspect, a predicative marker occurs in transitive clauses (Mandinka yè,

as in (1a), Soninke dà, as in (2a)), but not in intransitive clauses. In intransitive

clauses, the completive aspect is marked by a verbal suffix -ta in Mandinka, zeromarked in Soninke.

(3) Yíróo bòyí-tà

sílòo kâŋ.

MDK tree.D fall-CPL.ITR road.D on

S

V

X

‘The tree fell down on the road.’

(4) Wùllê-n ló

kónpè-n dí.

SNK dog.D enter room-D in

S

V

X

‘The dog went into the room.’

6

7.

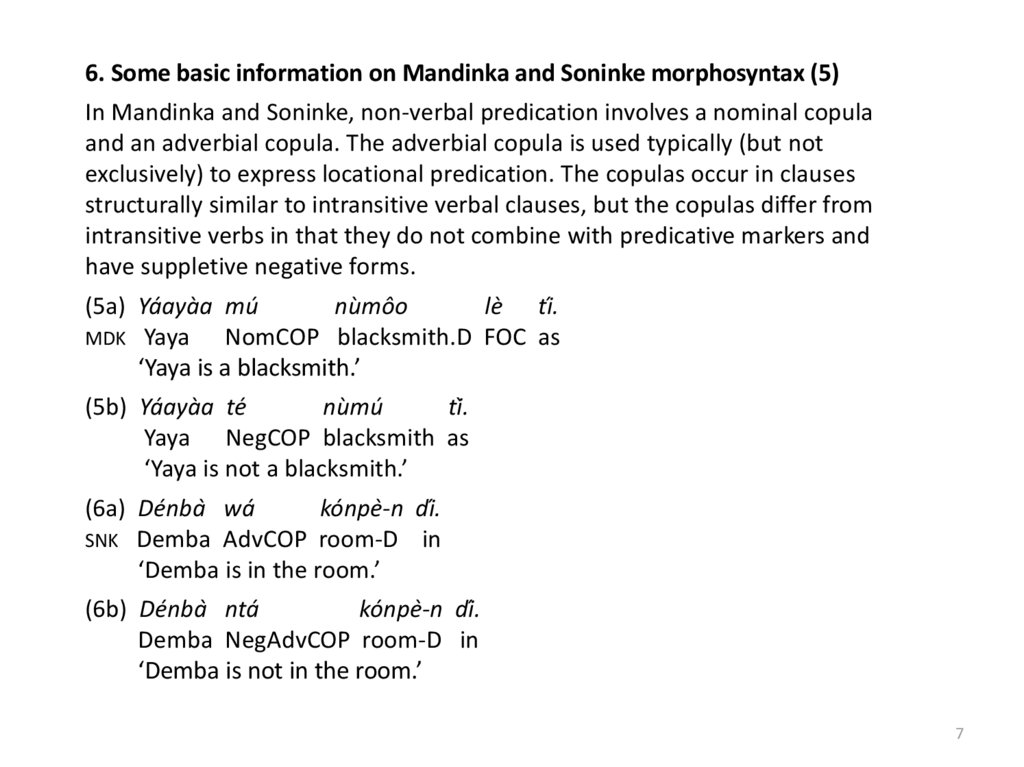

6. Some basic information on Mandinka and Soninke morphosyntax (5)In Mandinka and Soninke, non-verbal predication involves a nominal copula

and an adverbial copula. The adverbial copula is used typically (but not

exclusively) to express locational predication. The copulas occur in clauses

structurally similar to intransitive verbal clauses, but the copulas differ from

intransitive verbs in that they do not combine with predicative markers and

have suppletive negative forms.

(5a) Yáayàa mú

nùmôo

lè tí.

MDK Yaya

NomCOP blacksmith.D FOC as

‘Yaya is a blacksmith.’

(5b) Yáayàa té

nùmú

tì.

Yaya NegCOP blacksmith as

‘Yaya is not a blacksmith.’

(6a) Dénbà wá

kónpè-n dí.

SNK Demba AdvCOP room-D in

‘Demba is in the room.’

(6b) Dénbà ntá

kónpè-n dí.

Demba NegAdvCOP room-D in

‘Demba is not in the room.’

7

8.

7. Some basic information on Mandinka and Soninke morphosyntax (6)Non-verbal predication interferes with verbal predication in two ways. On the

one hand, the expression of TAM variation requires using copular verbs

(‘become’ for nominal predication, ‘be found’ for adverbial predication) instead

of the non-verbal copulas. On the other hand, the adverbial copula is also used

as a predicative marker in verbal clauses.

8

9.

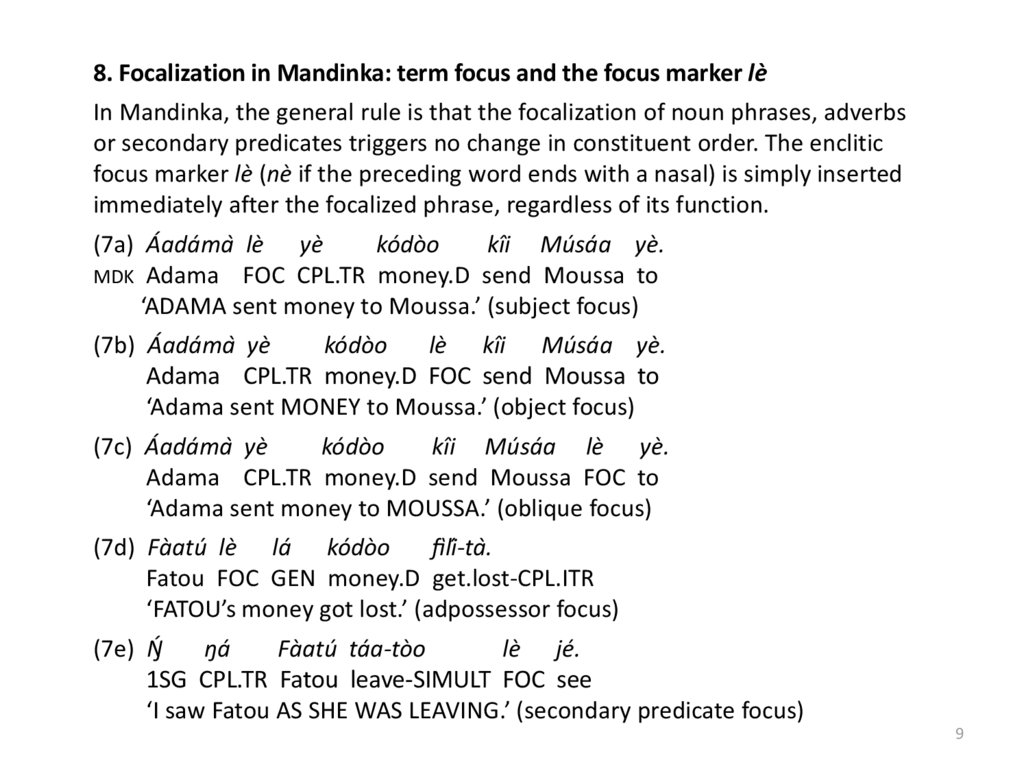

8. Focalization in Mandinka: term focus and the focus marker lèIn Mandinka, the general rule is that the focalization of noun phrases, adverbs

or secondary predicates triggers no change in constituent order. The enclitic

focus marker lè (nè if the preceding word ends with a nasal) is simply inserted

immediately after the focalized phrase, regardless of its function.

(7a) Áadámà lè yè

kódòo

kîi Músáa yè.

MDK Adama FOC CPL.TR money.D send Moussa to

‘ADAMA sent money to Moussa.’ (subject focus)

(7b) Áadámà yè

kódòo

lè kîi Músáa yè.

Adama CPL.TR money.D FOC send Moussa to

‘Adama sent MONEY to Moussa.’ (object focus)

(7c) Áadámà yè

kódòo

kîi Músáa lè yè.

Adama CPL.TR money.D send Moussa FOC to

‘Adama sent money to MOUSSA.’ (oblique focus)

(7d) Fàatú lè lá kódòo

fìlí-tà.

Fatou FOC GEN money.D get.lost-CPL.ITR

‘FATOU’s money got lost.’ (adpossessor focus)

(7e) Ŋ́

ŋá

Fàatú táa-tòo

lè jé.

1SG CPL.TR Fatou leave-SIMULT FOC see

‘I saw Fatou AS SHE WAS LEAVING.’ (secondary predicate focus)

9

10.

9. Focalization in Mandinka: the particular case of temporal adjunctsTemporal adjuncts differ from the other obliques in that they can be topicalized

by moving to the left periphery of the clause without being resumed by a

pronoun or adverb. They also differ from all other types of constituents by

their ability to be focalized in a position on the left periphery of the clause.

This construction requires special marking by means of lè mú (optionally

realized as lǒŋ), where lè is the general focus marker, and mú is the nominal

copula. Note that the second part of the construction is not different from a

plain independent clause, so that the construction has the appearance of a

juxtaposition of two independent clauses.

(8) Ñàŋkúmòo-lú kôomá lè mú

MDK cat.D-PL

behind FOC NomCOP

ñínòo-lú

kà tántánlúwóo lǒo.

mouse.D-PL ICPL dancing.circle set.up

‘It’s in the absence of cats that mice form the dancing circle.’

lit. It’s in the absence of cats, mice form the dancing circle.

10

11.

10. Focalization in Mandinka: negation and term focus (1)The focalization of noun phrases or adverbs in negative clauses (as in English

It’s John who did’nt come) is easy to elicit with consultants.

(9) Fàatú lè máŋ

nǎa bǐi.

MDK 1SG FOC CPL.NEG come today

‘It’s Fatou who didn’t come today.’

It is, however, remarkable that focalization in negative clauses does not occur

in my corpus of naturalistic texts with the meaning of exclusive identification

of a non-participant in a given event, but only with other values, as will be

commented below.

11

12.

11. Focalization in Mandinka: negation and term focus (2)As regards negative focalization (as in English It’s not John who came),

Mandinka has no grammaticalized construction expressing this meaning. The

only way to express negative focalization is by combining relativization and

negative nominal predication into a plain cleft construction expressing the

meaning of negative focalization compositionally (10a). This is also the only

possibility for rendering negative focalization in a negative clause (10b).

(10a) Míŋ nǎa-tá

bǐi, Fàatú ǹté.

MDK REL come-CPL.ITR today Fatou NegCOP

‘The one who came today, it’s not Fatou.’

(10b) Mîŋ máŋ

nǎa bǐi,

Fàatú ǹté.

REL CPL.NEG come today Fatou NegCOP

‘The one who didn’t come today, it’s not Fatou.’

However, such pain cleft constructions are extremely rare in spontaneous

discourse, contrasting with the very high frequency of positive clauses in which

the mere insertion of lè expresses the exclusive identification of a participant in

a presupposed event.

12

13.

12. Focalization in Mandinka: focalization and restriction (1)In positive clauses, phrases marked by one of the two restrictive particles dóróŋ

or dàmmâa ~ dàmmâŋ ‘only’ are also marked by the focus marker lè following

the restrictive particle. In their use as restrictive particles attached to noun

phrases or adverbs.

(11a) Ŋ́ sí wǒo dóróŋ nè kée nǒo

í

yè.

MDK 1SG POT DEM only FOC do be.able 2SG for

‘It’s the only thing I can do for you.’

lit. ‘I can do ONLY THAT for you.’

(11b) Ŋ́ nǎa-tà

ítè dóróŋ nè yé jǎŋ.

1SG come-CPL.ITR 2SG only FOC for here

‘It’s only for you that I came here.’

lit. ‘I came for YOU ONLY here.’

(11c) Fàatú dàmmâa lè nǎa-tà?

Fatou only

FOC come-CPL.ITR

‘Did Fatou come alone?’

lit. ‘Did FATOU ONLY come?’

13

14.

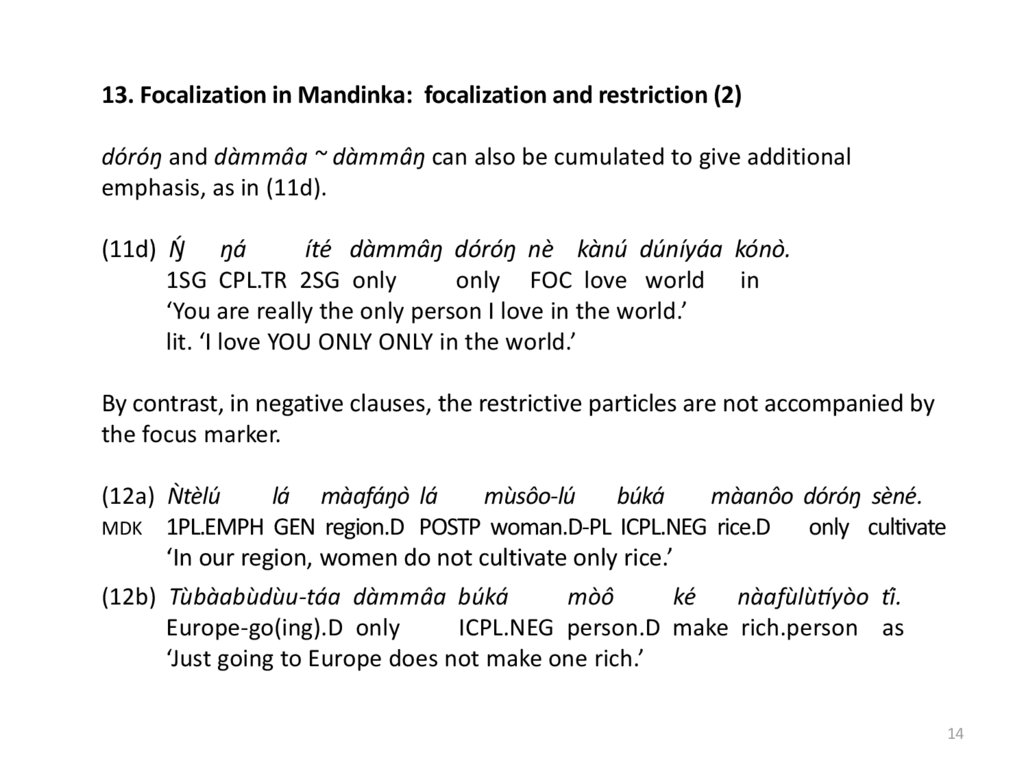

13. Focalization in Mandinka: focalization and restriction (2)dóróŋ and dàmmâa ~ dàmmâŋ can also be cumulated to give additional

emphasis, as in (11d).

(11d) Ŋ́ ŋá

íté dàmmâŋ dóróŋ nè kànú dúníyáa kónò.

1SG CPL.TR 2SG only

only FOC love world in

‘You are really the only person I love in the world.’

lit. ‘I love YOU ONLY ONLY in the world.’

By contrast, in negative clauses, the restrictive particles are not accompanied by

the focus marker.

(12a) Ǹtèlú

lá màafáŋò lá

mùsôo-lú

búká

màanôo dóróŋ sèné.

MDK 1PL.EMPH GEN region.D POSTP woman.D-PL ICPL.NEG rice.D

only cultivate

‘In our region, women do not cultivate only rice.’

(12b) Tùbàabùdùu-táa dàmmâa búká

mòô

ké

nàafùlùtíyòo tí.

Europe-go(ing).D only

ICPL.NEG person.D make rich.person as

‘Just going to Europe does not make one rich.’

14

15.

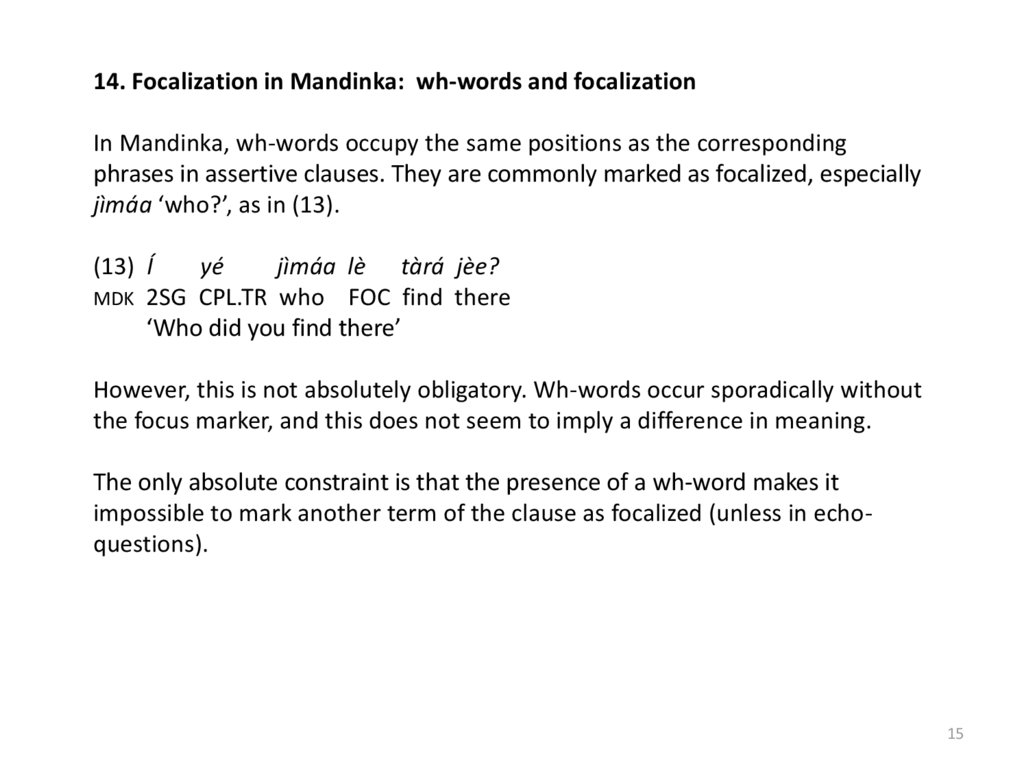

14. Focalization in Mandinka: wh-words and focalizationIn Mandinka, wh-words occupy the same positions as the corresponding

phrases in assertive clauses. They are commonly marked as focalized, especially

jìmáa ‘who?’, as in (13).

(13) Í

yé

jìmáa lè tàrá jèe?

MDK 2SG CPL.TR who FOC find there

‘Who did you find there’

However, this is not absolutely obligatory. Wh-words occur sporadically without

the focus marker, and this does not seem to imply a difference in meaning.

The only absolute constraint is that the presence of a wh-word makes it

impossible to mark another term of the clause as focalized (unless in echoquestions).

15

16.

15. Focalization in Mandinka: subordination and term focusThe focalization of noun phrases or adverbs is impossible in relative clauses

and some other types of subordinate clauses.

By contrast, in complement clauses introduced by kó (quotative /

complementizer) the focus marker lè can be used in the same way as in

independent clauses.

16

17.

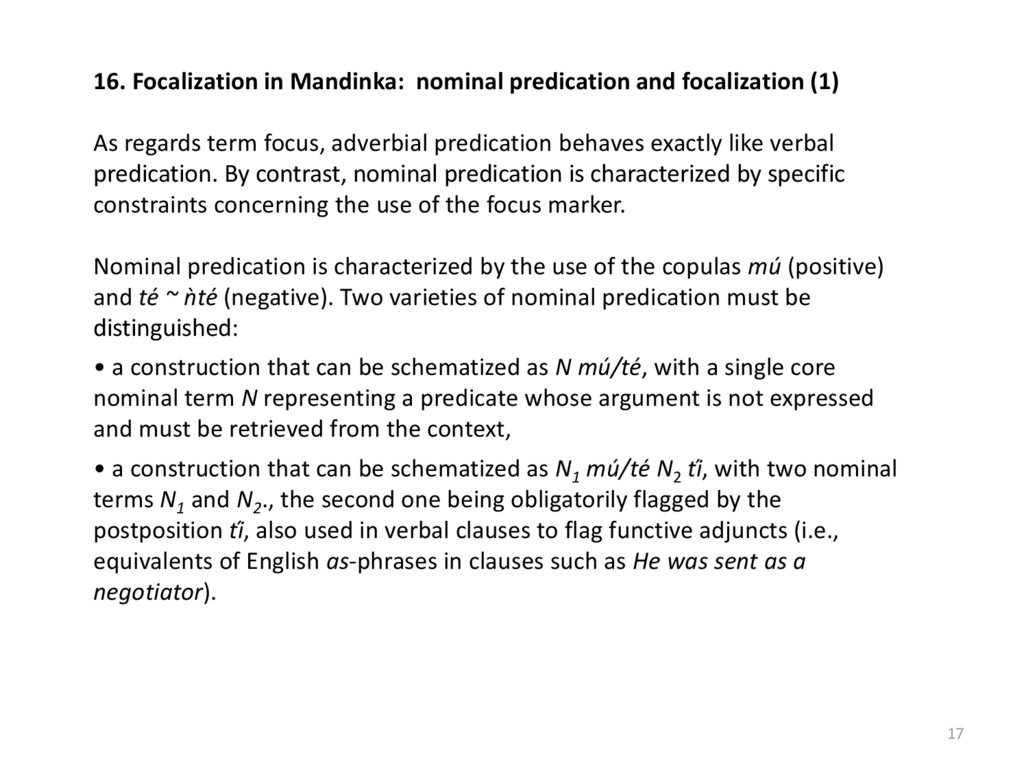

16. Focalization in Mandinka: nominal predication and focalization (1)As regards term focus, adverbial predication behaves exactly like verbal

predication. By contrast, nominal predication is characterized by specific

constraints concerning the use of the focus marker.

Nominal predication is characterized by the use of the copulas mú (positive)

and té ~ ǹté (negative). Two varieties of nominal predication must be

distinguished:

• a construction that can be schematized as N mú/té, with a single core

nominal term N representing a predicate whose argument is not expressed

and must be retrieved from the context,

• a construction that can be schematized as N1 mú/té N2 tí, with two nominal

terms N1 and N2., the second one being obligatorily flagged by the

postposition tí, also used in verbal clauses to flag functive adjuncts (i.e.,

equivalents of English as-phrases in clauses such as He was sent as a

negotiator).

17

18.

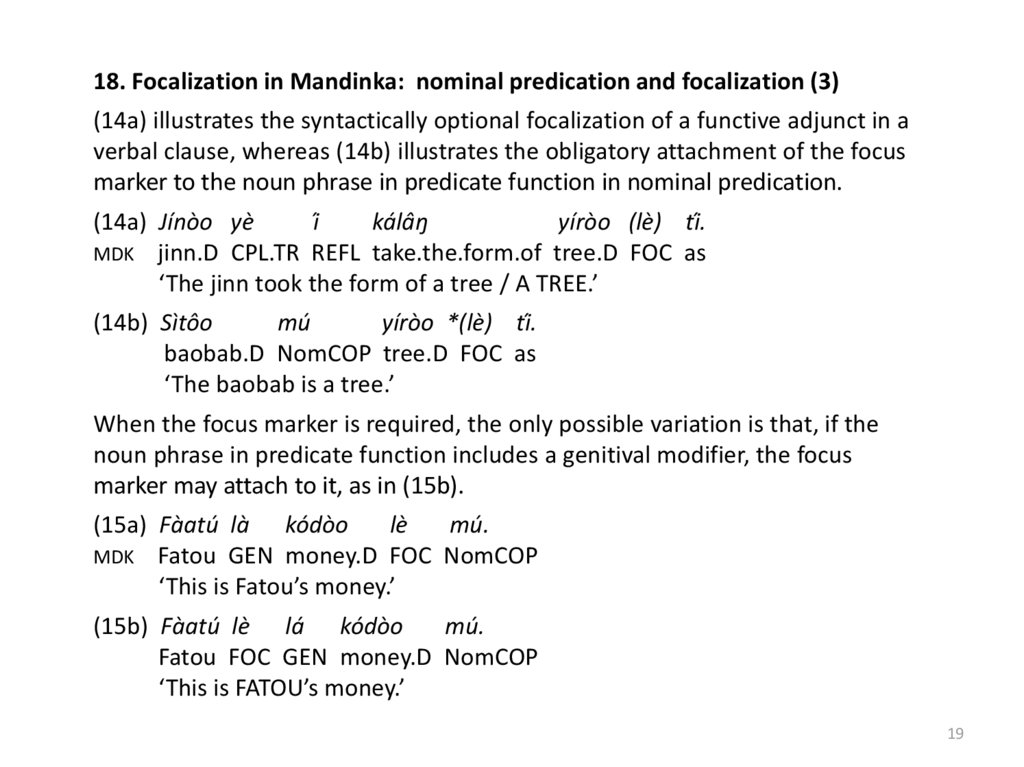

17. Focalization in Mandinka: nominal predication and focalization (2)In verbal or adverbial predication, the focus marker is never syntactically

obligatory, and when it is present, it can attach to any nominal term.

In nominal predication, in the conditions in which the general rule is that term

focalization by means of lè is impossible (for example, in relative clauses),

term focalization is impossible in nominal predication too.

By contrast, in the conditions in which the rule in verbal clauses is that term

focalization by means of lè is optional, in nominal predication, the presence of

the focus marker is obligatory, and it can only attach to the noun phrase in

predicate function.

18

19.

18. Focalization in Mandinka: nominal predication and focalization (3)(14a) illustrates the syntactically optional focalization of a functive adjunct in a

verbal clause, whereas (14b) illustrates the obligatory attachment of the focus

marker to the noun phrase in predicate function in nominal predication.

(14a) Jínòo yè

í

kálâŋ

yíròo (lè) tí.

MDK jinn.D CPL.TR REFL take.the.form.of tree.D FOC as

‘The jinn took the form of a tree / A TREE.’

(14b) Sìtôo

mú

yíròo *(lè) tí.

baobab.D NomCOP tree.D FOC as

‘The baobab is a tree.’

When the focus marker is required, the only possible variation is that, if the

noun phrase in predicate function includes a genitival modifier, the focus

marker may attach to it, as in (15b).

(15a) Fàatú là kódòo

lè

mú.

MDK Fatou GEN money.D FOC NomCOP

‘This is Fatou’s money.’

(15b) Fàatú lè lá kódòo

mú.

Fatou FOC GEN money.D NomCOP

‘This is FATOU’s money.’

19

20.

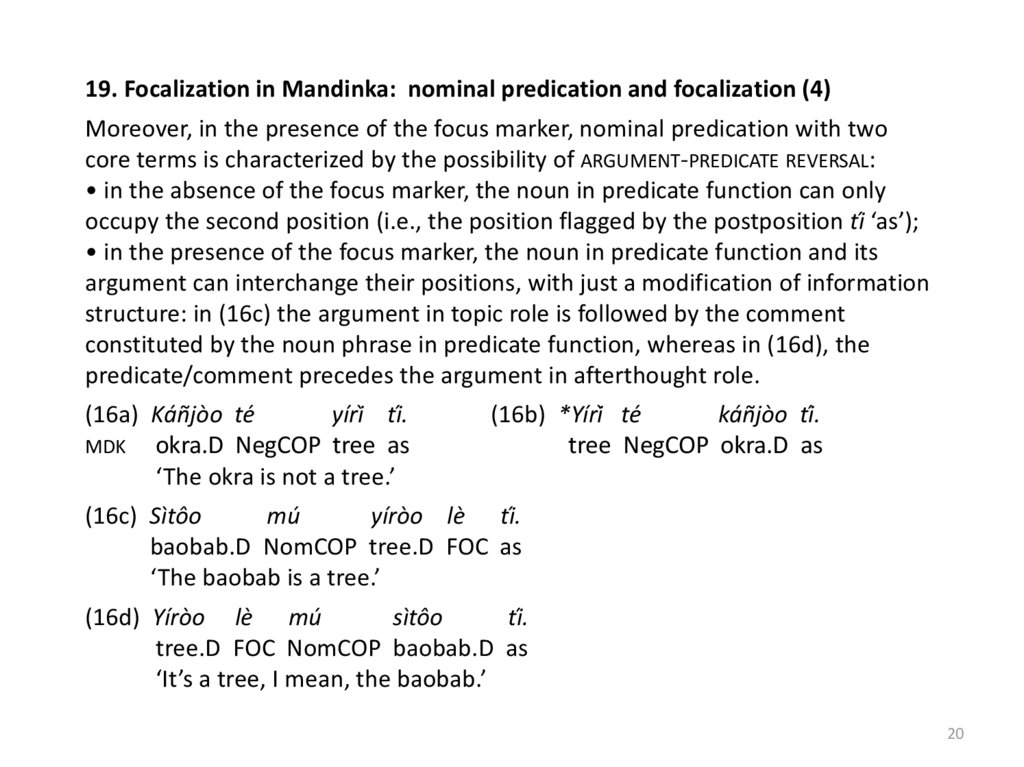

19. Focalization in Mandinka: nominal predication and focalization (4)Moreover, in the presence of the focus marker, nominal predication with two

core terms is characterized by the possibility of ARGUMENT-PREDICATE REVERSAL:

• in the absence of the focus marker, the noun in predicate function can only

occupy the second position (i.e., the position flagged by the postposition tí ‘as’);

• in the presence of the focus marker, the noun in predicate function and its

argument can interchange their positions, with just a modification of information

structure: in (16c) the argument in topic role is followed by the comment

constituted by the noun phrase in predicate function, whereas in (16d), the

predicate/comment precedes the argument in afterthought role.

(16a) Káñjòo té

yírì tí.

MDK okra.D NegCOP tree as

‘The okra is not a tree.’

(16b) *Yírì té

káñjòo tí.

tree NegCOP okra.D as

(16c) Sìtôo

mú

yíròo lè tí.

baobab.D NomCOP tree.D FOC as

‘The baobab is a tree.’

(16d) Yíròo lè mú

sìtôo

tí.

tree.D FOC NomCOP baobab.D as

‘It’s a tree, I mean, the baobab.’

20

21.

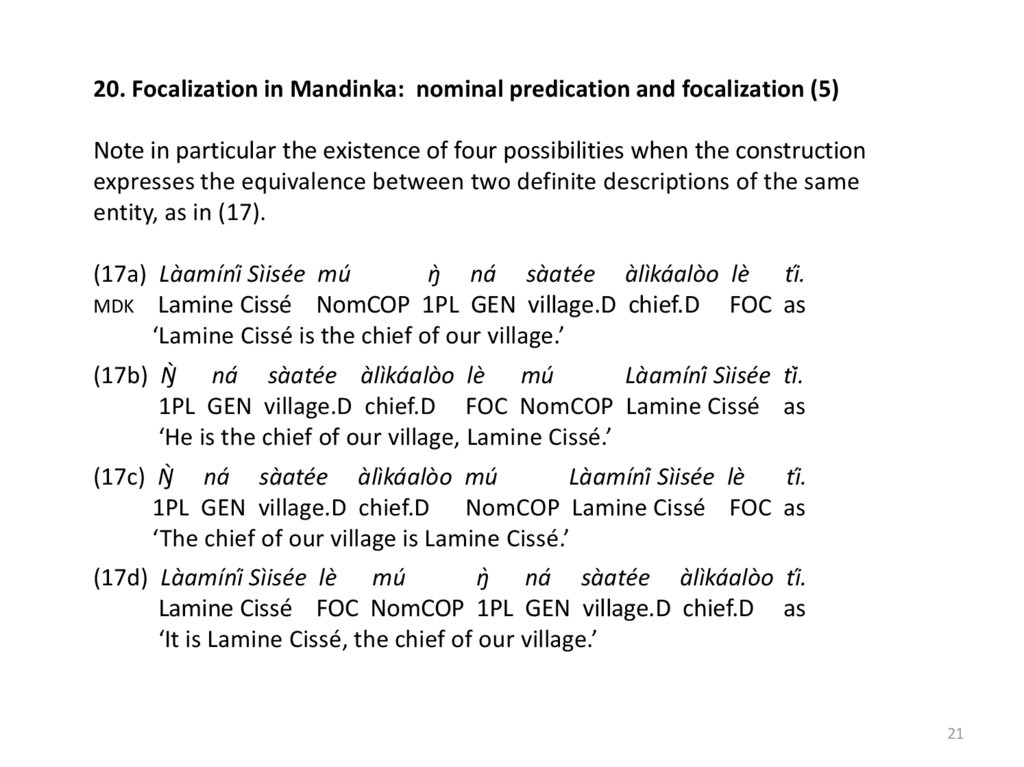

20. Focalization in Mandinka: nominal predication and focalization (5)Note in particular the existence of four possibilities when the construction

expresses the equivalence between two definite descriptions of the same

entity, as in (17).

(17a) Làamíní Sìisée mú

ŋ̀ ná sàatée àlìkáalòo lè tí.

MDK Lamine Cissé NomCOP 1PL GEN village.D chief.D FOC as

‘Lamine Cissé is the chief of our village.’

(17b) Ŋ̀ ná sàatée àlìkáalòo lè mú

Làamíní Sìisée tì.

1PL GEN village.D chief.D FOC NomCOP Lamine Cissé as

‘He is the chief of our village, Lamine Cissé.’

(17c) Ŋ̀ ná sàatée àlìkáalòo mú

Làamíní Sìisée lè

tí.

1PL GEN village.D chief.D NomCOP Lamine Cissé FOC as

‘The chief of our village is Lamine Cissé.’

(17d) Làamíní Sìisée lè mú

ŋ̀ ná sàatée àlìkáalòo tí.

Lamine Cissé FOC NomCOP 1PL GEN village.D chief.D as

‘It is Lamine Cissé, the chief of our village.’

21

22.

21. Focalization in Mandinka: term focus constructions that do not expressexclusive identification of participants (1)

An important aspect of grammaticalized term focus constructions, in contrast to

plain clefts, is the possible development of functions other than the exclusive

identification of a participant in a presupposed event. A first example is the use

of the focus marker in the expression of comparison: starting from a clause

expressing that an entity has a given property (18a), a comparative construction

can be formed by adding an oblique tí-phrase representing the standard, and by

focalizing the comparee, as in (18b).

(18a) Kàlâa lá tíñáaróo wàrá-tà.

MDK pen.D GEN damage.D be.big-CPL.ITR

‘The pen causes a lot of damage.’

lit. ‘The pen’s damage is big.

(18b) Kàlâa lè lá tíñáaróo wàrá-tá

tàmbôo tí.

pen.D FOC GEN damage.D be.big-CPL.ITR spear.D in.comparison.with

‘The pen causes more damage than the spear.’

lit. ‘The PEN’s damage is big in comparison with the spear.’

22

23.

22. Focalization in Mandinka: term focus constructions that do not expressexclusive identification of participants (2)

A second example is the use of a term focus construction to single out a

prominent participant in a sentence explaining the current situation. For

example, in the context from which (19) has been extracted, it could not be

felicitously replaced by a sentence unambiguously implying reference to a

presupposed love affair (such as The one she loves is a sàayêe fish). This

sentence could rather be paraphrased as ‘What explains her behavior is that

she is in love, and her lover is a sàayêe fish’.

(19) À

kà mîŋ bêe ké těŋ, à

kà sàayêe lè kànú.

MDK 3SG ICPL REL all do thus 3SG ICPL sàayêe FOC love

‘Everything she is doing, it’s because she is in love with a sàayêe fish.’

lit. ‘Everything she does, she loves A SAAYEE FISH.’

In (19), the assertion is about a presupposed event (the strange behavior of the

girl, referred to as À kà mîŋ bêe ké těŋ), but the remainder of the sentence

consists of new information presented as explaining the girl’s behavior. The

focus marker attached to sàayêe highlights the role of a particular participant

(‘What’s happening is that she is in love, and the object of her love is a sàayêe),

but does not reflect an articulation between presupposition and assertion.

23

24.

23. Focalization in Mandinka: term focus constructions that do not expressexclusive identification of participants (3)

Similarly, the meaning expressed by the main clause in (20) cannot be

glossed as ‘What is hurting him is his right hand’, since nothing in the context

implies that something is hurting the person in question. The intended

meaning is rather as ‘What’s happening is that something is hurting him, and

it’s his right hand’.

(20) Níŋ í

yé

kèebáa

màrâa

jé kínòo kónò

MDK if 2SG CPL.TR oldman.D left.hand.D see meal.D in

à

búlúbàa

lè kà à dímîŋ.

3SG right.hand.D FOC ICPL 3SG hurt

‘If you see an oldman eating with his left hand, it’s because his right

hand is painful.’

lit. ‘If you see an oldman eating with his left hand, HIS RIGHT HAND is

painful.’

24

25.

24. Focalization in Mandinka: term focus constructions that do not expressexclusive identification of participants (4)

As already mentioned, my corpus includes no occurrence of the focus marker

in negative clauses with the meaning of exclusive identification of a nonparticipant in a given event, but negative clauses expressing an explanation in

which a non-participant playing a key role is focalized, such as (21), are

common.

(21) Níŋ í

yè

móoròo

jé sèewù-sùbù-ñímòo lá,

MDK if

2SG CPL.TR marabout.D see pig-meat-eat(ing).D POSTP

bàa-súbòo lè tí

jěe.

goat-meat.D FOC NegCOP there

‘If you see a marabout eating pork, it’s because there is no goat meat

available.’

lit. ‘If you see a marabout eating pork, GOAT MEAT is not there.’

25

26.

25. Focalization in Mandinka: verb focus (1)When encliticized to the verb or to the verb phrase, lè expresses emphasis on

the particular action or process expressed by the verbal lexeme, in opposition to

some other action or process (either mentioned in the context or implied), but

can also be interpreted as emphasizing the whole sentence or clause.

(22a) Bàa-mùsù-bâa yè

kùlúŋò míŋ jìijâa,

MDK goat-female-old CPL.TR mortar.D REL rock

à díŋò bé

à bòyìndì-lá

lè.

3SG kid.D AdvCOP 3SG make.fall-GER FOC

‘The mortar that the old goat rocked, its kid will OVERTURN it

(22b) Í

màŋ

ñánnà í

là dómóféŋò dáanì-lá,

2SG CPL.NEG must 2SG GEN food

beg-GER

í

ñân-tá

dòokúwòo kélà

lè.

2SG must-CPL.ITR work.D

do-GER FOC

‘You should not beg for your food, you should WORK.’

(22c) Ŋ́

ŋá

í

kànú lè dóróŋ,

1SG CPL.NEG 2SG love FOC only

wó lè yè

ŋ́ fànìyà-ndí

í

yè

DEM FOC CPL.TR 1SG tell.lies-CAUS 2SG to

‘I just LOVE you, this is what made me tell you lies.’

26

27.

26. Focalization in Mandinka: verb focus (2)Example (23) illustrates the contrast between lè inserted between a noun

phrase in oblique role and the postposition that marks its function (23a), and

lè following a postpositional phrase (23b). In (23a), lè focalizes the noun

phrase, whereas in (23b), it focalizes the verb phrase.

(23a) À táa-tà kúŋkòo lè tó.

MDK 3SG go-CPL.ITR field.D FOC to

[Where did Yaya go?] He went to THE FIELD.

(23b) À táa-tà kúŋkòo tó lè.

3SG go-CPL.ITR field.D to FOC

[How is it that Yaya is not here?] He WENT TO THE FIELD.

This use of the focus marker is much more frequent in Mandinka than in the

other Manding languages, and in Mandinka, the emphasis expressed in this

use of the focus marker is rather weak, as evidenced by the fact that

sentences with lè marking verb focus are often spontaneously given by

informants in elicitation without any apparent reason. This particularity of

Mandinka is probably due to the long-lasting contact with Atlantic languages,

in which the grammaticalization of verb focus is common.

27

28.

27. Focalization in Soninke: introductory remarks (1)Although Manding languages and Soninke belong to relatively distant subbranches of the Western branch of the Mande family, their syntactic structures

are strikingly similar. This is probably the result of intense contact.

By contrast, Soninke has a much richer morphology than Manding languages,

both segmentally and tonally. This general characterization applies in particular

to the focalization system.

Soninke has an enclitic focus marker `yá (`ñá after a word ending with a nasal).

The notation `yá means that the underlying tonal contour of this clitic is LH.

However, since in Soninke, contour tones are not allowed at surface level, it

surfaces as yá or yà depending on the tonal context.

28

29.

28. Focalization in Soninke: introductory remarks ( 2)Within the limits of the data I have been able to gather, the syntactic properties

of `yá are not different from those of Mandinka lè, apart from the fact that the

use of the focus marker in wh-questions is less common in Soninke than in

Mandinka.

By contrast, focalization in Soninke is involved in differential subject flagging (a

mechanism that does not exist in Mandinka), and triggers several other

morphological phenomena that have no equivalent in Mandinka.

In the remainder of the presentation, I will not repeat the description of the

distribution of the focus marker, since with the exception just mentioned, the

indications given in §3 about the distribution of Mandinka lè also apply to

Soninke `yá. I will concentrate on the morphological manifestations of

focalization other than the mere presence of the focus marker `yá.

29

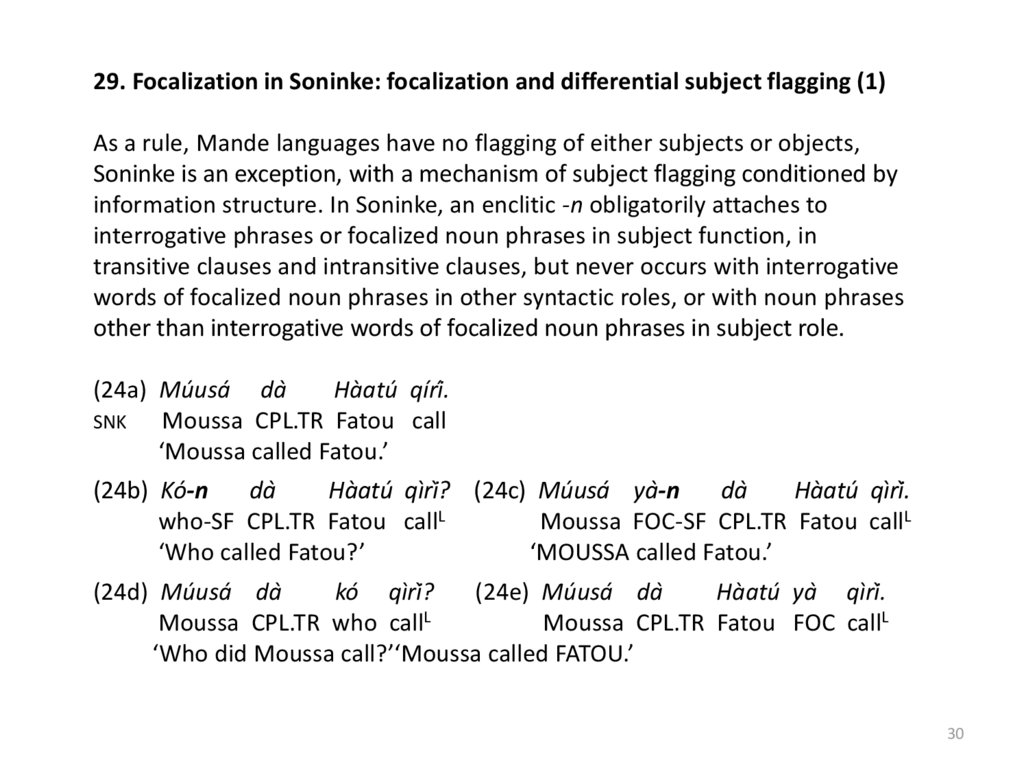

30.

29. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and differential subject flagging (1)As a rule, Mande languages have no flagging of either subjects or objects,

Soninke is an exception, with a mechanism of subject flagging conditioned by

information structure. In Soninke, an enclitic -n obligatorily attaches to

interrogative phrases or focalized noun phrases in subject function, in

transitive clauses and intransitive clauses, but never occurs with interrogative

words of focalized noun phrases in other syntactic roles, or with noun phrases

other than interrogative words of focalized noun phrases in subject role.

(24a) Múusá dà

Hàatú qírí.

SNK

Moussa CPL.TR Fatou call

‘Moussa called Fatou.’

(24b) Kó-n

dà

Hàatú qìrì? (24c) Múusá yà-n

dà

Hàatú qìrì.

who-SF CPL.TR Fatou callL

Moussa FOC-SF CPL.TR Fatou callL

‘Who called Fatou?’

‘MOUSSA called Fatou.’

(24d) Múusá dà

kó qìrì?

(24e) Múusá dà

Hàatú yà qìrì.

Moussa CPL.TR who callL

Moussa CPL.TR Fatou FOC callL

‘Who did Moussa call?’‘Moussa called FATOU.’

30

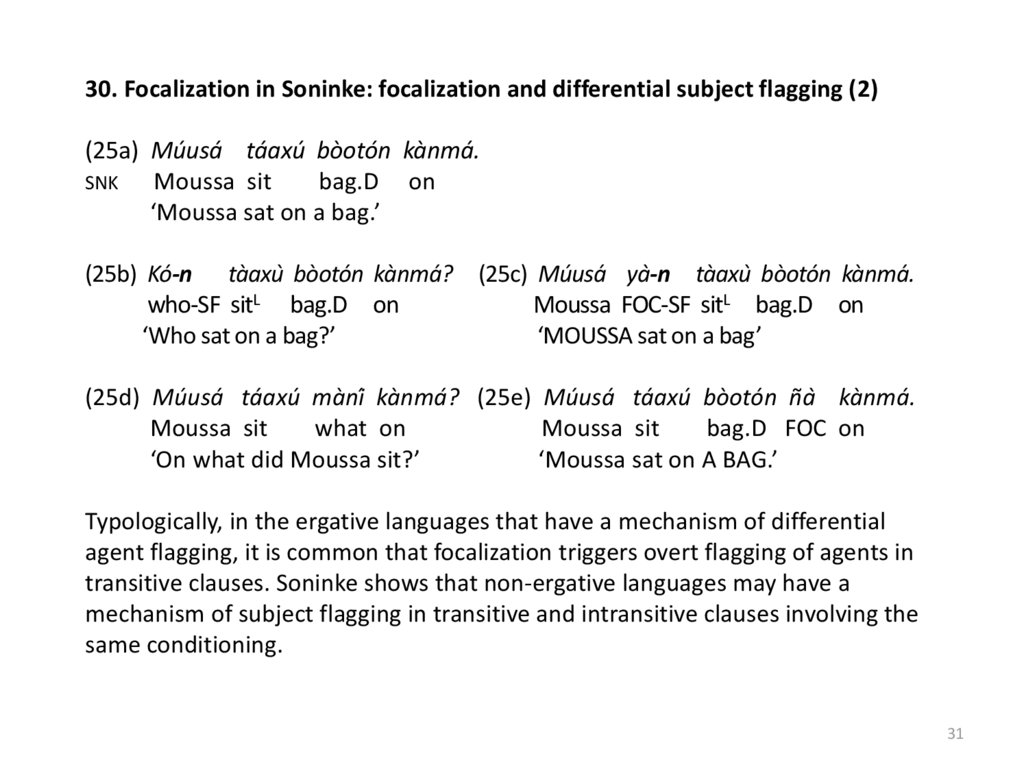

31.

30. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and differential subject flagging (2)(25a) Múusá táaxú bòotón kànmá.

SNK

Moussa sit

bag.D on

‘Moussa sat on a bag.’

(25b) Kó-n tàaxù bòotón kànmá? (25c) Múusá yà-n tàaxù bòotón kànmá.

who-SF sitL bag.D on

Moussa FOC-SF sitL bag.D on

‘Who sat on a bag?’

‘MOUSSA sat on a bag’

(25d) Múusá táaxú màní kànmá? (25e) Múusá táaxú bòotón ñà kànmá.

Moussa sit

what on

Moussa sit

bag.D FOC on

‘On what did Moussa sit?’

‘Moussa sat on A BAG.’

Typologically, in the ergative languages that have a mechanism of differential

agent flagging, it is common that focalization triggers overt flagging of agents in

transitive clauses. Soninke shows that non-ergative languages may have a

mechanism of subject flagging in transitive and intransitive clauses involving the

same conditioning.

31

32.

31. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and the tonal inflection of verbs (1)Soninke verbs have a tonal inflection with two forms: a form in which the verb

shows its lexical tonal contour, and a form in which all verbs, whatever their

lexical tone, show an entirely L tone pattern. Note that, in Soninke, no verb

has an entirely L contour as its lexical tonal contour.

In (26a) and (26c), the verbs qírí ‘call’ and séllà ‘sweep’ show their lexical tone

pattern (HH and HL, respectively), whereas in (26b) and (26d), the negative

predicative markers má (completive negative) and ntá (incompletive negative)

trigger the replacement of the lexical tone pattern by the L tone pattern.

(26a) Ó dà

Múusá qírí.

SNK 1PL CPL.TR Moussa call

‘We called Moussa.’

(26b) Ó má

Múusá qìrì.

1PL CPL.NEG Moussa callL

‘We didn’t call Moussa.’

(26c) Ń

ŋá ké kónpé séllà-ná.

1SG ICPL DEM room sweep-GER

‘I am sweeping this room.’

(26d) Ń ntá

ké kónpé sèllà-nà.

1SG ICPL.NEG DEM room sweep-GERL

‘I am not sweeping this room.’

32

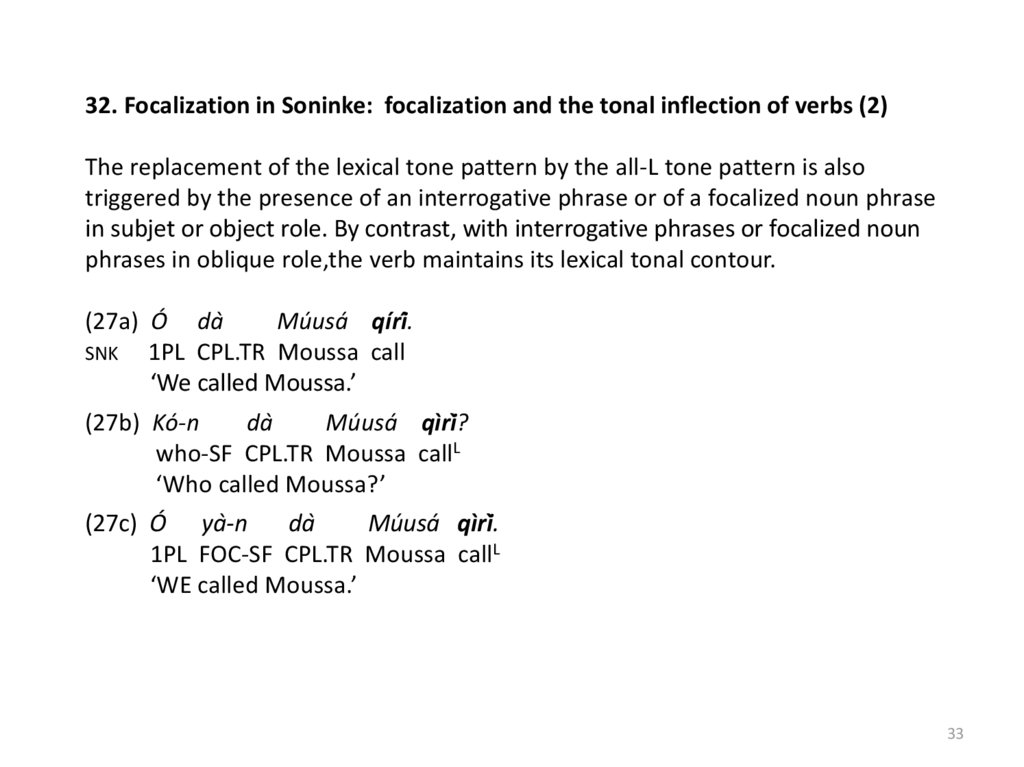

33.

32. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and the tonal inflection of verbs (2)The replacement of the lexical tone pattern by the all-L tone pattern is also

triggered by the presence of an interrogative phrase or of a focalized noun phrase

in subjet or object role. By contrast, with interrogative phrases or focalized noun

phrases in oblique role,the verb maintains its lexical tonal contour.

(27a) Ó dà

Múusá qírí.

SNK 1PL CPL.TR Moussa call

‘We called Moussa.’

(27b) Kó-n

dà

Múusá qìrì?

who-SF CPL.TR Moussa callL

‘Who called Moussa?’

(27c) Ó yà-n

dà

Múusá qìrì.

1PL FOC-SF CPL.TR Moussa callL

‘WE called Moussa.’

33

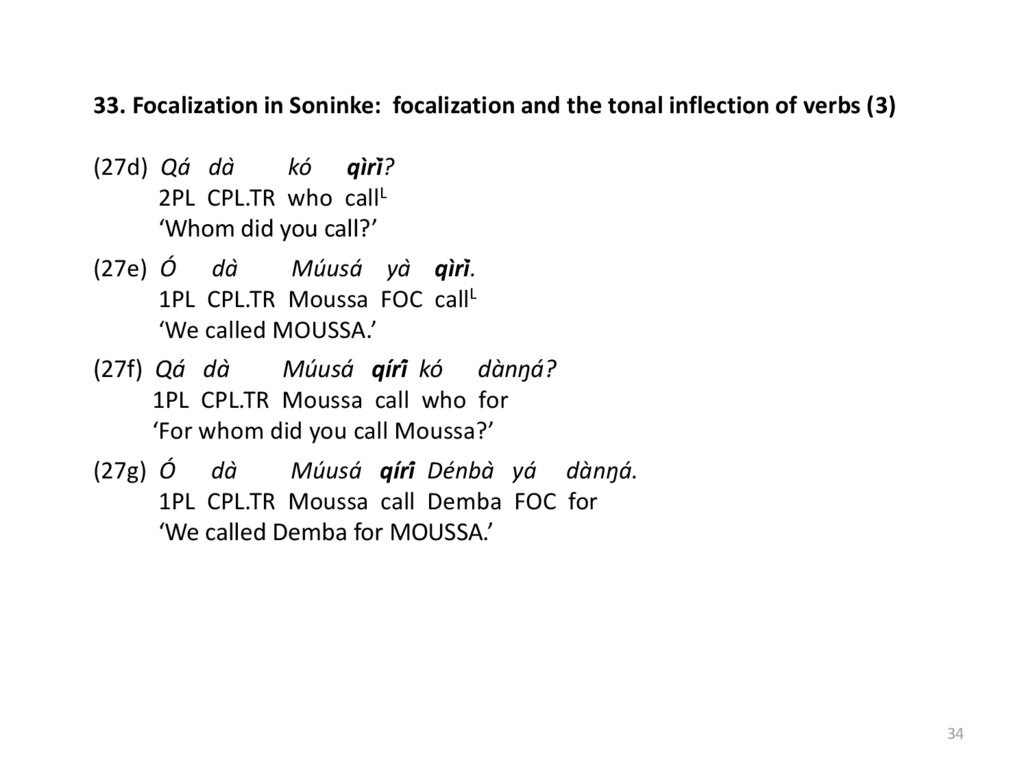

34.

33. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and the tonal inflection of verbs (3)(27d) Qá dà

kó qìrì?

2PL CPL.TR who callL

‘Whom did you call?’

(27e) Ó dà

Múusá yà qìrì.

1PL CPL.TR Moussa FOC callL

‘We called MOUSSA.’

(27f) Qá dà

Múusá qírí kó dànŋá?

1PL CPL.TR Moussa call who for

‘For whom did you call Moussa?’

(27g) Ó dà

Múusá qírí Dénbà yá dànŋá.

1PL CPL.TR Moussa call Demba FOC for

‘We called Demba for MOUSSA.’

34

35.

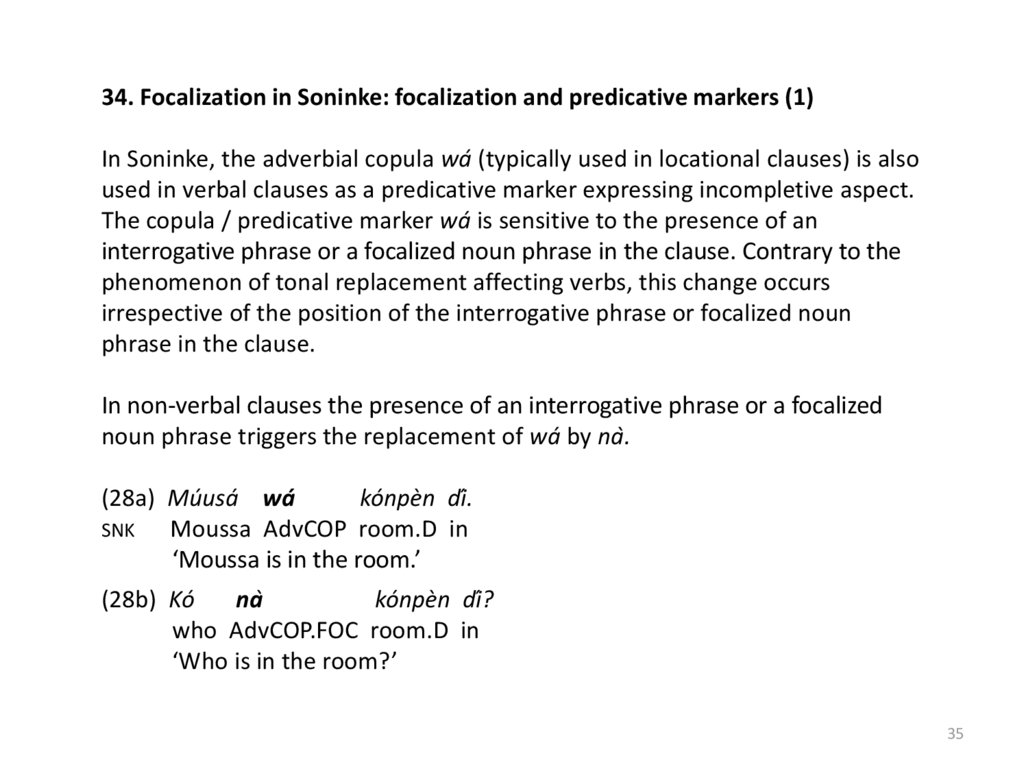

34. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and predicative markers (1)In Soninke, the adverbial copula wá (typically used in locational clauses) is also

used in verbal clauses as a predicative marker expressing incompletive aspect.

The copula / predicative marker wá is sensitive to the presence of an

interrogative phrase or a focalized noun phrase in the clause. Contrary to the

phenomenon of tonal replacement affecting verbs, this change occurs

irrespective of the position of the interrogative phrase or focalized noun

phrase in the clause.

In non-verbal clauses the presence of an interrogative phrase or a focalized

noun phrase triggers the replacement of wá by nà.

(28a) Múusá wá

kónpèn dí.

SNK

Moussa AdvCOP room.D in

‘Moussa is in the room.’

(28b) Kó

nà

kónpèn dí?

who AdvCOP.FOC room.D in

‘Who is in the room?’

35

36.

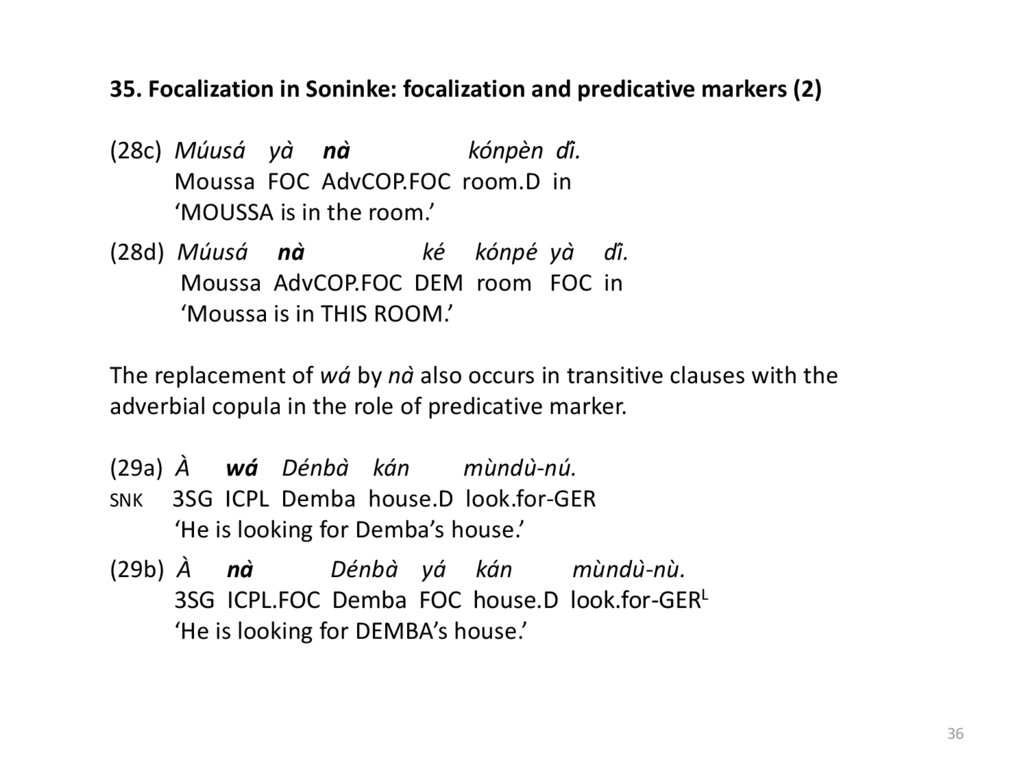

35. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and predicative markers (2)(28c) Múusá yà nà

kónpèn dí.

Moussa FOC AdvCOP.FOC room.D in

‘MOUSSA is in the room.’

(28d) Múusá nà

ké kónpé yà dí.

Moussa AdvCOP.FOC DEM room FOC in

‘Moussa is in THIS ROOM.’

The replacement of wá by nà also occurs in transitive clauses with the

adverbial copula in the role of predicative marker.

(29a) À wá Dénbà kán

mùndù-nú.

SNK 3SG ICPL Demba house.D look.for-GER

‘He is looking for Demba’s house.’

(29b) À nà

Dénbà yá kán

mùndù-nù.

3SG ICPL.FOC Demba FOC house.D look.for-GERL

‘He is looking for DEMBA’s house.’

36

37.

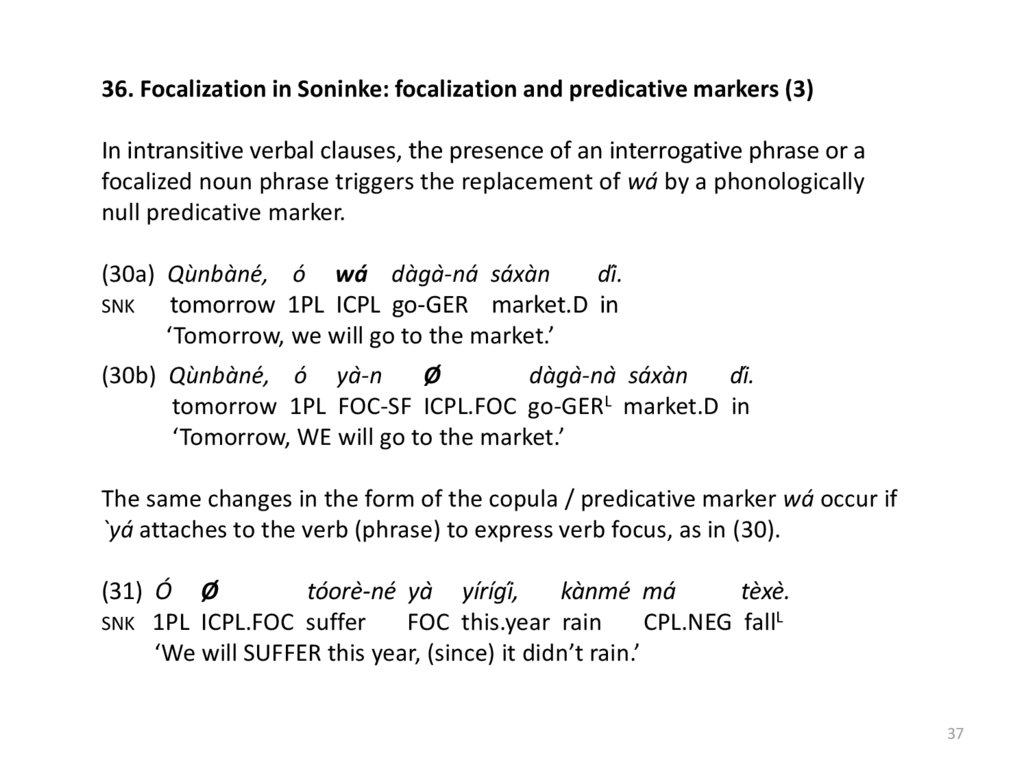

36. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and predicative markers (3)In intransitive verbal clauses, the presence of an interrogative phrase or a

focalized noun phrase triggers the replacement of wá by a phonologically

null predicative marker.

(30a) Qùnbàné, ó wá dàgà-ná sáxàn

dí.

SNK

tomorrow 1PL ICPL go-GER market.D in

‘Tomorrow, we will go to the market.’

(30b) Qùnbàné, ó yà-n

Ø

dàgà-nà sáxàn

dí.

tomorrow 1PL FOC-SF ICPL.FOC go-GERL market.D in

‘Tomorrow, WE will go to the market.’

The same changes in the form of the copula / predicative marker wá occur if

`yá attaches to the verb (phrase) to express verb focus, as in (30).

(31) Ó Ø

tóorè-né yà yírígí,

kànmé má

tèxè.

SNK 1PL ICPL.FOC suffer

FOC this.year rain

CPL.NEG fallL

‘We will SUFFER this year, (since) it didn’t rain.’

37

38.

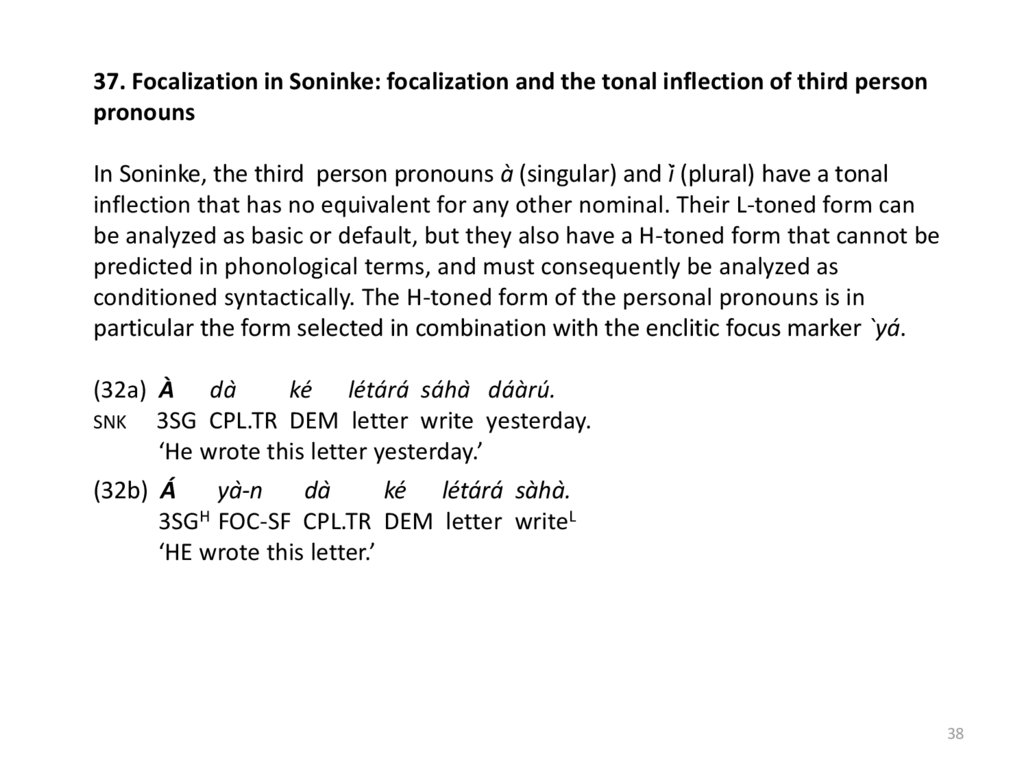

37. Focalization in Soninke: focalization and the tonal inflection of third personpronouns

In Soninke, the third person pronouns à (singular) and ì (plural) have a tonal

inflection that has no equivalent for any other nominal. Their L-toned form can

be analyzed as basic or default, but they also have a H-toned form that cannot be

predicted in phonological terms, and must consequently be analyzed as

conditioned syntactically. The H-toned form of the personal pronouns is in

particular the form selected in combination with the enclitic focus marker `yá.

(32a) À dà

ké létárá sáhà dáàrú.

SNK 3SG CPL.TR DEM letter write yesterday.

‘He wrote this letter yesterday.’

(32b) Á

yà-n

dà

ké létárá sàhà.

3SGH FOC-SF CPL.TR DEM letter writeL

‘HE wrote this letter.’

38

39.

38. ConclusionIn this presentation, after describing the syntactic properties of the Mandinka

focus marker, I have described the various phenomena conditioned by the

presence of the focus marker in Soninke.

The interest of this comparison is to show that two languages may have

focalization devices quite similar syntactically, with, however, a sharp contrast

in terms of morphological complexity.

In Mandinka, the insertion of the enclitic focus marker in a construction has

no incidence on the remainder of the construction, whereas in Soninke, the

insertion of the focus marker interferes with several mechanisms that have no

necessary relationship with focalization, which contributes to enhancing the

distinction between plain assertive clauses and clauses involving focalization:

• differential subject flagging,

• the tonal inflection of verbs,

• the form of the adverbial copula (also used as a predicative marker in verbal

clauses),

• the tonal inflection of personal pronouns.

39

40.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION40

lingvistics

lingvistics